Ellen Fries discovered Agneta Horn’s autobiography in the Celsius collection at Uppsala University Library in 1885. It was a sensational find, and she immediately published excerpts in the feminist journal Dagny. One of the very first Nordic autobiographies, it had been written in the mid-seventeenth century and been holed up in the archives ever since.

Agneta Horns Leverne (1908; The Autobiography of Agneta Horn)was followed by a slew of women’s diaries and memoirs in the first few decades of the new century. Malla Silfverstolpe’s well-known Memoarer (Memoirs) of the early nineteenth century were finally published by one of her female descendants. Carl Carlson Bonde and Cecilia af Klercker published the diaries of Queen Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta (1759-1818), while Cecilia Bååth-Holmberg brought out Adelaide von Hauswolff’s En svensk flickas dagbok under krigsfångenskap i Ryssland 1808–1809 (The Diary of a Young Swedish Woman in Russian Captivity, 1808-1809).

The first generation of well-educated women had set out in pursuit of their predecessors, and the publication of these documents signalled the birth of a new historiography.

As the Swedish feminist movement gathered momentum in the first few decades of the twentieth century, women began to publish their autobiographies. When Sweden introduced universal suffrage in the 1920s, a number of established authors used the autobiographical genre to tell their story and forge their artistic identity. And that was only the beginning. The trend peaked in the 1940s, once again due to historical circumstances. During the period that men were called up for the army, women’s social status rose. Just as decisive was the fact that the first women who had assumed their rightful place in various spheres of society, fought for universal suffrage, and participated in peace and justice movements had now reached the traditional age of autobiographers.

The publication of old autobiographies and diaries reflected both growing interest and greater feminine self-assuredness; the number of such documents increased throughout the first two decades of the twentieth century. Quite a few of them, including Familjen Johan Ekmans krönika (1914; The Chronicle of the Johan Ekman Family) by Hedda Ekman (1860-1929) and Släktanteckningar (1916; Family Notes) by Hilda Petri (1851-?), had a semi-private flavour. Originally written for a narrow circle of relatives, they were published in limited edition only. Ekman’s book is interesting not only for its detailed description of early twentieth century family life, but for the way that it blends various genres. It is a cross between a journal, family album (she was a leading photographer), and memoir. While the level of detail in her portrayal of everyday life is both profuse and suggestive, she is terse when it comes to herself. As was typical of many female autobiographers, Ekman tells her own story by means of hints and revealing omissions. Her narrative of childhood and youth, which her family kept to itself until the late 1880s because of its “sensitive” nature, says a good deal about how difficult it was for women’s autobiographies to see the light of day. Having grown too fond of Viktor Rydberg, an ageing poet and friend of the family, she had been sent away to a boarding school for girls in Switzerland.

Also typical of women’s autobiographies was that they shared many features of cultural history. Söder om landsvägen (1916; South of the Highway) and Från pilträdens land och syrenernas stad (1918; From the Land of the Willows and the City of Lilacs) by Emma Bendz (1858-1927) frequently subordinate the story of the protagonist to a description of the town of Lund, southern Sweden, and all the odd people she meets there, while revealing titbits about herself through those very encounters. Ett barns litterära memoarer (1917; A Child’s Literary Memoirs), a curious little volume by Hedvig Amalia af Petersens (1875-1961), takes a similarly indirect cultural-historical approach by discussing the books she read as a child. Using Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s Fänrik Ståhls sägner (1898; The Legends of Ensign Ståhl, Eng. tr. The Songs of Ensign Stål), Ivar Arosenius’s Kattresan (1909, Journey with a Cat), Tom Sawyer, Little Women, and other classics as a springboard, the narrative meanders along slyly and circuitously, but nimbly and almost graciously. Although she once said that she had written the book to cope with life’s woes, little of that heaviness comes through. When her mother died in 1911, she left her job as a journalist for Stockholms Dagblad and returned to the southern countryside to take care of her father. She later gained a reputation as a privately educated scholar, took long trips to Australia and New Zealand, and published a number of literary studies and travelogues.

Petersens’s journalistic career led to another book of great interest: Den undre världen (1907; The Underworld) by Anna Mathilda Cecilia Johannesdotter Johansson (1877-1906). While writing a series about the women’s prison in Landskrona, Petersens met Anna Johannesdotter, a prostitute since the age of nineteen who was three years her junior and had been in and out of jail for several years. She was suffering from a severe case of tuberculosis, and Petersens tried to help her in various ways. Before Johannesdotter died at the age of twenty-eight, she gave her handwritten autobiography to her benefactress. Klara Johanson, a critic for Stockholms Dagblad, took charge of publishing it.

Johannesdotter’s fate is far from unusual in the history of autobiographies. Although a victim of a man’s world in many ways, she comes through as tenacious and strong-willed. Her style is unpolished, heavily influenced by Christian confessional and penitential writing, but the book is sprinkled with vivid descriptions of an innocent childhood, as well as with the cunning and coarseness that she acquired as an adult. By turns self-accusatory and assertive – a streak of rebelliousness runs through the narrative, and the attached police records show that she was sentenced for disorderly conduct or obstructing an officer over and over again – she is ever her own advocate. Her artless chronicle is an indictment of a society that has condemned her to degradation, illness, and hardship, but also an affirmation of pride, integrity, and determination, and her goal is just as much to recover her lost honour as to exhibit regret for her transgressions.

Anna Johannesdotter, a domestic servant, first kissed a man at the 1897 General Art and Industrial Exposition of Stockholm (World’s Fair). Her autobiography, Den undre världen (1907; The Underworld), proceeds immediately from that incident to her life as a prostitute. When Gerda Kjellberg (1881-1972) ran into her French relatives at the same exhibition, they offered to take her back to Paris so that she could receive a medical education.

The promise turned out to be empty, and she ended up as the family’s unpaid servant instead. Nevertheless, her ramblings through the streets of Paris opened her eyes to the degradation of women, and she would spend the rest of her life struggling against it.

Jag anklagar (1916; I Accuse) by Laura Petri (1879-1959) is even blunter about the longing for redemption. She furiously attacks her superiors at the Salvation Army and the staff of the mental hospitals. She and Johannesdotter were at opposite ends of the social spectrum. While Johannesdotter was a victim of injustice in need of benefaction, Petri was a charity worker. But they wrote from the same perspective. For giving full vent to their sexuality, society ostracised and deprived them of their liberty. Petri is circumspect about why her superiors committed her. Apparently she had been caught in an amorous affair that she refused to either deny or atone for. Though depressed and tormented by religious brooding, she wanted to fight her way out of it by working. Arguing that she was suffering from overexertion, however, her family and superiors had her confined to various ‘rest homes’, where she was strapped to the bed and subjected to cold baths for days on end.

Nilsson’s Glimtar ur mitt liv som läkare dramatically chronicles her interaction with prostitutes as a gynaecologist and periodically as a medical officer:

“Every once in a while I would run into some of my patients on Hantverkargatan Street, and I reflexively nodded to them just as I would any other patient. One day a two-woman delegation walked up and read me the riot act. How dare I greet them? Imagine if I were in the company of a gentleman. He would have to lift his hat – and what if he turned out to be one of their customers?” “My encounter with the problem – both human and abstract – of prostitution often left me weary and despondent as the years went by”, writes Ada Nilsson in Glimtar ur mitt liv som läkare (1963; Glimpses into My Life as a Doctor). “The more I talked with prostitutes, the more complicated things got, particularly when it came to their customers. Later on I asked a Salvationist, ‘Don’t you ever try to talk to the men?’ ‘No,’ she answered, ‘In that case, we would have to start with members of Parliament. Remember the Farmers’ March of 1914 – the brothels were bursting at the seams every night.’”

Nilsson found herself at the centre of the struggle for women’s rights in the early years of the twentieth century. She was a force behind the formation of the Association of Liberal Women (later the Left Federation of Swedish Women) in 1914, and she helped edit its magazine Tidevarvet from 1924 to 1936.

Sweden was in a state of flux in the late nineteenth century. The economy was fundamentally restructured, and the flight from the rural to urban areas accelerated. Technological progress transformed living conditions. Old social structures collapsed and new ones emerged amidst waves of turbulence. If Johannesdotter fell into the chasm and Petri teetered on the edge, Wilhelmina Skogh (1849-1926) made the most of the bracing heights.

Like Johannesdotter, she grew up in the countryside. She left the island of Gotland for Stockholm at the age of twelve and took a job at the Strömparterren Restaurant, where she dried glasses from nine in the morning until one at night. “Lord how I suffered, but it was good for me, because I learned how to work efficiently”, she wrote in Minnen och hågkomster (1912: Memories and Recollections). Fifty years had passed by that time, and she had made a sterling career for herself in the rapidly expanding restaurant industry. Minnen och hågkomster is the story of a self-made woman. Poor and disadvantaged, she works her way up the social ladder by dint of unrelenting effort and a powerful imagination. Skogh found herself at the heart of a restaurant industry that had sprung up on the back of the newly constructed railway network. She was made manager of the railway hotel in Storvik, a town in the Dalarna province, and ran it so well that she soon could build one of her own. Before long, she owned three hotels in the most scenic area of Sweden and was developing an embryonic tourist industry. One of her biggest drawing-cards was King Oscar II, who often stayed at one of her establishments on the way to or from the opening of a railway line. She went to Italy to pick up a few pointers and introduced a number of innovations, fresh vegetables being at the top of the list. She stretched a telephone line between her hotels, which she equipped with greenhouses and steam engines. When the General Art and Industrial Exposition of Stockholm (World’s Fair) rolled around in 1897, she was appointed manager of all the hotels. Several years later she became the chief executive of the Grand Hotel in Stockholm, and crowned her career by building the Grand Hotel Royal with its famous Italian-style winter garden. In 1911, she retired to Villa Foresta, her newly built palace nestled among the cliffs of Lidingö Island. She wrote her autobiography, published in 1912, from an elevated position, both literally and figuratively.

Jag anklagar (1916; I Accuse) by Laura Petri is a long tirade against the treatment to which she was subjected. Though highly specific and detailed, the book leaves a remarkably vague overall impression. While telling an appalling story of defencelessness and impotence, it also depicts a woman of incredible strength, stamina, and integrity. She is released from her “prison” after two years, and the book marks the beginning of a long writing career, including two doctoral theses in theology, only one of which was accepted. The other thesis was about the Salvation Army, which she left in 1913.

Conquering the Written Word

Largely due to well-established authors like Selma Lagerlöf, Mathilda Malling, Helena Nyblom, and Marika Stiernstedt, women’s autobiographies acquired greater literary status in the Sweden of the 1920s. At first glance, such works may appear to be simply margin notes – documentary evidence of their lives behind, alongside of, or prior to their art. Not unexpectedly, however, the autobiographies fully reflect the professions of their authors. They vary greatly. Mina levnadsminnen (1922; Memories of My Life) by Helena Nyblom (1843-1926) consists largely of recollections and disconnected mental images of scenes and individuals – as is the case with Mitt och de mina (1926; 1930; My Family and I) I-II, by Marika Stiernstedt (1875-1954). Uppfostran och inflytande (1922; Upbringing and Influence) and Mina dagböcker (1926; My Diaries) by Mathilda Malling (1864-1942), and Mårbacka (1922; Eng. tr. Mårbacka), Ett barns memoarer (1930; Memories of My Childhood), and Dagbok (1932; Eng. tr. The Diary of Selma Lagerlöf) by Selma Lagerlöf, on the other hand, are highly refined and artistically inspired narratives.

Från Fyrisån till Capris klippor (1931; From the Fyrisån River to the Cliffs of Capri) and Från Norrström till Arno (1932; From the Norrström River to the Arno) by Ellen Lundberg pick up the thread of the family saga that her mother, author Helena Nyblom, began with Mina levnadsminnen (1922; Memories of My Life). And it is not the only autobiography that permits the reader to follow women from one generation to the next.

Hemmet med de öppna dörrarna (1939; The Home with Open Doors) by Greta Holmgren fills out the description of early family life that her mother Ann Margret Holmgren had sketched in Minnen och tidsbilder (1926; Memories and Images). Min långa resa (1945; My Long Journey) by Anna Branting tells a very different story of domestic life than Brantings på Norrtullsgatan (1939; The Brantings of Nortullsgatan Street) by her daughter Vera von Kraemer.

What all these autobiographers had in common, however, was that they focused more on their writing than their personal lives. Of equal importance is that they furnish their readers with clear instructions for interpreting their works.

Mathilda Malling’s autobiographical books also describe the emergence of a writer. At two different stages of her career, she wrote of her life before the scandal of 1884. There is little doubt that she was out to defend herself. During the first stage, she used every means at her disposal to keep her life and art separate. “That anyone would associate me with the charming enchantress Bertha Funcke never occurred to me for a moment,” she writes in Uppfostran och inflytande (1922; Upbringing and Influence). Malling, whose youthful pseudonym Stella Kleve came to embody obscenity in Swedish literature at the end of the nineteenth century, wanted to reinterpret her career in the autumn of her life – not so much what she had written in 1884-1888, which she more or less rejected, but the relationship between the author and her art, as in the novel Bertha Funcke (1895; Bertha Funcke).

“When little Selma happens to overhear Miss Subert’s atheistic pronouncements in Dagbok”, writes Lars Ulvenstam in his foreword to the 1958 trilogy, “she has two diametrically opposed reactions in the two drafts and a third reaction in the final version. That makes at least two alternatives too many.” The autobiography’s earnest tone can easily seduce the reader into taking the facts literally. Many scholars and critics have used the three volumes as a key to understanding her art. A more interesting way to read them is as the end-point, and possibly the culmination, of her many stories and narratives, along with Löwensköldska ringen (1925; Eng. tr. The General’s Ring), Charlotte Löwensköld (1925; Eng. tr. Charlotte Löwensköld), and Anna Svärd (1928; Eng. tr. Anna Svärd, 1931). While often remaining on a pure storytelling level, her autobiographical works possess a rare existential flavour, taking her trademark naive and playful cadence to its ultimate conclusion.

World War I had a paralysing influence on Selma Lagerlöf’s productivity, but she wrote a biography of Zacharias Topelius in the late 1910s at the urging of the Swedish Academy. Many critics and scholars have argued that the protagonist more closely resembles the author herself than the Finnish poet, and that the book represented a step on the path towards her later autobiographical works.

She starts off in the third person. In Mårbacka, an ageing author named Selma Lagerlöf tells Selma, a little girl, a story about a girl who has lost everything – love, protection, security, joy, and the ability to walk – but is taken by her family to the bird of paradise, which brings her back to life. “Strömstadsresan” (Journey to Strömstad), the first and most blatantly autobiographical section of the book, describes the genesis of her writing career. With her father’s assistance, she meets her muse for the first time. Lieutenant Lagerlöf’s charm wins them an invitation to visit the ship where the bird of paradise dwells, and his boyish enthusiasm carries them onboard. At that point, however, Selma is left to her own devices. Only the little cabin boy understands what she wants. He takes her hand to show her the way to the bird; she gets up and walks on her own to the cabin.

In her encounter with the bird of paradise, the little girl Selma regains her ability to walk. Equally important, “She had learned to see,” as the section concludes: “It was thanks to that journey that she remembered her nearest and dearest as they were in their prime when life was a joy to them. But for that, everything related to those times would have faded out of mind.” Lagerlöf grafts her identity as an author onto the four-year-old girl. It is the beginning of all things, and the section follows the trajectory of dizzying descent, great effort, and giddy redemption that appears in novel after novel, starting with Gösta Berlings saga (1891; Eng. tr. The Story of Gösta Berling).

“Remember”, says the red satin ribbon that she takes home from Strömstad, and the autobiography presents her entire writing career as one long effort to recall the past.

Mårbacka is the story of how Lagerlöf came to be a writer. She tells it over and over again. Her father constantly reappears as the unrivalled cavalier, boisterous and playful, full of pranks, irresistible, and loved by everyone. The introduction to the manuscript says, “Dear father, dear Lieutenant Lagerlöf, I want to write this story with you in mind,” and the book slowly assumes the shape of an everlasting homage to him. In “The Seventeenth of August”, the final chapter of the book, the whole district pours into Mårbacka to celebrate Lieutenant Lagerlöf’s birthday. The adulation is boundless, and the chapter in the manuscript ends with a jubilant tribute to “a man who smiled at life, who never met another person without a friendly word, who could work and make merry, who longed for beauty, who coveted splendour but accepted what life had to offer, who knew that he was universally liked, who could romp and play with children, who attracted young women to his side, and whom middle-aged wives smiled at, a blessed human being, a Värmlander, a cavalier.”

The immaculate, righteous father figure of the manuscript gives way in the book to a more complex character whose charming exterior barely conceals foibles, failures, and cowardice. “The New Mårbacka”, the fourth section of the book, is one long litany of Lieutenant Lagerlöf’s failures. Every step he takes turns out wrong. His plans are too grandiose, and he can never let go of them. He exhausts his wife’s inheritance long before it is paid out. In retrospect, Lagerlöf realises that her father’s imprudence and recalcitrance slowly but surely drove the estate into bankruptcy. His brother in law’s little speech, which concludes the published version of Mårbacka, paints a complex picture: “You are no big important man. You have done no great outstanding thing. But you have within you the best of goodwill and an open heart. We know that, were it in your power, you would take the whole world in your embrace.”

Lagerlöf’s father clearly played a major role in both her life and art. The fundamental importance that her mother assumed in her life manifested itself less directly. A mother’s tears caused an abyss to open at the little girl’s feet. Old and decrepit, beset by writer’s cramp while at work on the last part of her autobiography, Lagerlöf prayed to her mother. “Sick. Perhaps I am the one who has forsaken the spirits. A task that it is mine to perform”, she wrote on the back of the manuscript of Dagbok. “I pray to the spirit to guide my arm. God, my only spirit, help me. Teach me the proper style, Mother.”

Like Orpheus, Lagerlöf tries to charm her beloved father – the shadowy forms, all of which have his features – out of the grave with her art. But the process is anything but simple. And once the deconstructed tribute is over, she interrupts her autobiography to write the story once again. In what was to be her last great fiction project, the defrocked pastor – the good-for-nothing who has the world eating out of the palm of his hands, but who brings only devastation and ruin – reappears. In the story of the Löwenskölds, Karl-Artur Ekenstedt is the reincarnation of Gösta Berling without his potential for humility, maturity, and transformation. Love never fazes him; the heroines of Charlotte Löwensköld and Anna Svärd love him from the bottom of their hearts but eventually abandon him.

Lagerlöf then resumes the work on her autobiography, finally making the transition to the first person. In the second and third parts, the father figure literally wastes away. The first chapter of Ett barns memoarer tells of his return from a voyage in poor health. He never fully recovers and is portrayed in a radically different way. His seamy side gradually reveals itself. He exhibits despotic tendencies, rigidity, naïveté that borders on inanity and ultimately emotional cowardice as well. The book presents him in a wholly different light than Mårbacka. Once again, Lagerlöf redefines her male protagonist. “The Earthquake”, the final chapter of Ett barns memoarer depicts him as both pitiful and impotent.

The father is completely absent in Dagbok, the next volume of the autobiography. Time has taken a quantum leap forward. Selma is fourteen and preparing for a trip to Stockholm. Everybody stays up to say goodbye to her, “except Papa, of course.” On the train, she meets a young man, the Student, who arouses the same unconditional devotion that her father once had. In an ingenious metamorphosis, he takes her father’s place, unshackles her imagination, and becomes her muse. Meanwhile, he increasingly resembles the loveable but equivocal character who becomes the hero of Lagerlöf’s novels in ever changing guises.

Mårbacka, Ett barns memoarer, and Dagbok thrice rewrite the story of her artistic beginnings, and once more reframe the narrative that constantly inhabits her fiction. Mårbacka gives birth to the author, Ett barns memoarer relates her decision to pursue a writing career, and Dagbok teaches her how to transmute life into art.

Birgit Thomæus Sparre begins her long series of autobiographical works with the words, “When I was a child, the area around Lake Åsunden was called the Kingdom of Sparre.” Her prolific writing turned her into the uncrowned queen of the region. Gårdarna runt sjön (1928; The Manors around the Lake) was the first of her historical romances, which placed her in the ranks of the most popular twentieth century writers. The first part of her autobiography, Därhemma på gårdarna (1960; Home on the Manors) describes the world on which her works were based.

Travelogues and Life Stories

Jag for till Paris (1941; I Went to Paris) is the autobiography of Thora Dardel (1899-1995). The title sounds like a trumpet call. She made the trip in 1919 to train as a sculptress. Dardel belonged to the third generation of young Swedish women who sought their artistic fortunes in the capital of European culture. The odyssey plays a central role in the autobiographies that many of them published in the 1930s and 1940s.

“I woke up to a dreadful din from the streets and threw open the green shutters”, Elsa Hammar-Moeschlin (1879-1950) writes in Hjärtat och paletten (1937; The Heart and the Palette). “The quiet, humdrum mornings of East Stockholm were a distant memory. Life sang like a boisterous choir amidst the clamour of the boulevards.” The year was 1904. After attending Technical School – the forerunner of the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design – she had come to Paris to study painting with Christian Krohg. Real life, the life of the artist, had now begun. Two years later she continued on her way, constantly pursuing new motifs. Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany were among the places she visited before settling down in Switzerland with her husband. As was the case with many female artists of her time, her autobiography is an odd cross between a self-illustrated travelogue and the story of her life.

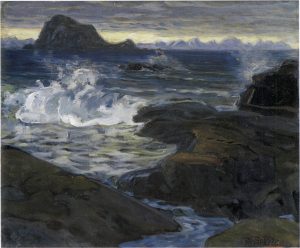

Anna Boberg (1864-1935) also studied in Paris for several years. But her most intimate relationship was with the landscape of northern Scandinavia. She achieved fame as a painter of the Lofoten countryside of Norway, the central theme of her autobiography Envar sitt ödes lekboll (1934; Everyone Is the Sport of Fortune). “After a week of outdoor life with the fishing village of Svolvaer as my base of operations, I was so enchanted by the natural beauty of Lofoten that I refused point blank to leave. I wanted to stay and do nothing but paint. My husband returned home through Trondhjem and sent me all the painting supplies I needed. So Fortune had indeed cast the die for me.”

While travelling on a scholarship, Elisabeth Bergstrand (1887-1955) met Danish sculptor Axel Poulsen at the Scandinavian Association in Rome. Thus, a journey that had passed through Paris, Sicily, and Algeria concluded in Denmark. She, too, trained as a sculptor, but ended up painting and writing instead. Her autobiography Hök, får jag låna dina vingar (1940; Hawk, May I Borrow Your Wings?) describes her as an author and painter, but most of the narrative is about her life as a daughter and wife. The book is abundantly illustrated with photographs from her travels and portraits of her children, though mostly of the house that she and her husband were building. Each stage of the process is fully documented – the outside from a number of different angles, and endless interior shots.

Tora Dardel went to Paris as an aspiring sculptress, but abandoned her ambition and chose writing instead. She married Swedish painter Nils Dardel who became her aesthetic ideal. “My dream was to write the way that he painted”, she explains in Jag for till Paris. Her first book was the novel Flickan som reste ensam (1923; The Girl Who Travelled Alone).

The core of Dardel’s autobiography is the artist’s milieu she lived in rather than her career. Her penthouse on the Left Bank was a watering hole for writers and artists like Jean Cocteau and Tristan Tzara, as well as his Swedish-born wife Greta Knutson. Eric and Greta Grate, Jules Pascin, Fernand Léger, Isaac Grünewald, and Sigrid Hjertén, along with Rolf de Maré – leader of the famous Ballets Suédois in Paris – were all members of their inner circle. Integral to life in the Scandinavian artists’ colony was Maison Watteau, a venue for art and artists that sculptress Lena Börjelson built in the late 1910s and described in intimate detail in her autobiography, Mitt livs lapptäcke: minnen från ett konstnärsliv (1957; The Patchwork Quilt: Memories of an Artist’s Life).

Just like Börjeson, Dardel portrays herself and her epoch through the lens of cultivated society. A steady stream of autobiographies by the female artists of the generation describes the Left Bank, its cafés and famous clientele: La Rotonde with its sawdust floor, its models, the beautiful Kicki de Montparnasse, and les filles de joie of Montmartre. Soirées, journeys, and unexpected encounters fill their pages. These artists were fully aware that they had crossed the boundaries not only of nations but of traditional femininity.

Ulla Bjerne (1890-1969) epitomised that consciousness. She appears in a number of paintings by the most prominent artists of the time. Nils Dardel’s 1914 work, which depicts her as a seductive tomboy, is the most famous. Her autobiographical trilogy Livet väntar dig (1955; Life Is Waiting for You), Den glada otryggheten (1958; Happy Insecurity), and Botad oskuld (1961; Innocence Cured) portrays a young woman with an inexorable yearning for freedom. She doggedly fights her way out of small-town Sweden, takes clerical jobs in Malmö, Trelleborg, and Copenhagen, and arrives in Paris, her sights set on freedom. The year is 1912 and war is not far off. She is twenty-two and financially dependent on a man who wants to marry her. She knows that she wants something else – just not what it is. Her life is a never-ending experiment. She crosses boundaries, lives freely, openly, and unreservedly. She designs her own culottes and has them made by the prostitutes’ tailors in Montmartre. Deliberately, she fashions a new, androgynous feminine ideal.

Bjerne describes her life as a non-stop adventure. But the story has a paradoxical and dubious ring to it. Written as though it were one of the lightweight picaresque novels she later published as an esteemed author, it nevertheless conceals hints of tragedy beneath its seductively jocular surface. Botad oskuld is largely a tale of disillusionment. A catastrophe sweeps away the happy ending that the reader has been led to expect. The experiment is unsuccessful. The liberation from convention that marks the artist colonies turns out to be synonymous with defencelessness as far as women are concerned, and men let them down once again.

Advance and retreat often walk side by side in the narrative of women’s quest. The encounter with a man frequently brings a woman back to the fate society has staked out for her, reorders her priorities, and causes her to settle down, to call it a day. But a few fascinating autobiographies follow her ongoing journey towards the borderlands of existence.

“It is this disability that has forced me to sit still, to look within myself, and that is the reason why I became a writer,” wrote Selma Lagerlöf to her friend Valborg Olander. “If I had been healthy like everybody else, I should probably have become the wife of some factory manager.” The teenage alter ego of the elderly Selma Lagerlöf in Dagbok writes: “I am beginning to think it is well that the student is betrothed. If I were married to him I would never have time to write stories, and that is what I have always longed to do.”

Aurora Nilsson (1894-1972), a Swede studying in Berlin, thought she was taking a fairly unremarkable step when she married an Afghan by the name of Asim Kahn in the 1920s. Strong and independent, she took care of him rather than the other way around. But their marriage turned out to be a long journey, both literally and metaphorically. It led her across land and sea, to a realm where the patriarchy she had learned to tame in Europe still reigned unchallenged. Flykten från harem (1928; Eng. tr. The Flight from a Harem) describes the transformation of her world to a prison whose doors slam shut one after another; her beloved husband turns into a ruthless despot, nobody believes what she has to say, and her struggle to escape grows increasingly desperate.

Women often came up with unassuming titles for their autobiographies. Words like glimpses, fragments, memories, and images appear over and over again. Mitt lilla åttiotal (1959; My Little Eighties) is the 1959 autobiography of Tora Vega Holmström, a prominent artist. Mitt liv i miniatyr (1944; My Life in Miniature) by Berta Wilhelmsson has a rather ambiguous title that alludes to her famous portraits.

Political and social activist Alma Hedin entitled her autobiography Min levnads arbetsdag (The Working Day of My Life). The manuscript is housed in the Women’s History Collections at the University of Gothenburg Library. I minnets blomstergårdar (1950; In the Flower Gardens of Memory) was the title of the sequel.

Inga Ehrström (1915-66) had no intention of becoming a writer when she and her two children followed her husband to Greenland. She saw herself simply as a loyal wife. But the sojourn made her one of Sweden’s most intriguing autobiographers.

A physician by profession, her husband wanted to study the health of a primitive people. The year in Greenland was a dizzying adventure accompanied by a series of hardships that they met in a spirit of joy and togetherness. Her husband found out on the way back to Sweden that he had cancer; her first two autobiographical works Slocknad är elden (1953; The Fire Has Been Extinguished) and Vid stranden av mitt hav (1955; On the Shore of My Ocean) were written under the shadow of his dying days. Ehrström says in the preface to Slocknad är elden that she wants to realise her husband’s dream of writing a popular book about Greenland. He spent the end of his life classifying the material that he had gathered. But the narrative is just as much a glowing eulogy as a travelogue.

Vid stranden av mitt hav hones her perspective. Chronicling their final months together, it is a song of songs in which every word resonates with sorrow.

Eight years later she set out on a fresh adventure with her seventeen-year-old daughter Christel. They spent two years travelling by jeep through destitute areas of South America. Ännu blommar våra träd: med jeep genom Argentina och Paraguay (1963; Our Trees Bloom Again: by Jeep through Argentina and Paraguay) and La Casita (1965; The House) relate their trials, tribulations, and impressions. History repeats itself. Once more a journey turns into a life-and-death struggle. Her daughter becomes mentally ill and commits suicide. La Casita, the lovely holiday cottage that a kind Dane lends the two women so that they can rest up after their long trip, is slowly transformed into hell on earth. Unaware that she herself suffers from an insidious form of blood poisoning, Ehrström looks helplessly on as her daughter fades into the shadows. Furious in their grief, La Casita and Ännu blommar våra träd tell of spectacular but horrifying encounters with lands unknown.

Into History

Writing an autobiography involves metaphorically revisiting the past, assessing and relating to previous experiences, deeds, and accomplishments. Particularly in the 1940s, many of the women who had participated in the early twentieth century struggle to transform society published autobiographies. In addition to recounting the fates of individual human beings, the books chronicle a decisive political and social chapter in history as far as women are concerned.

Gryningsflickan (1985; The Girl of the Dawn), a novel by Tomas Löfström, is a retelling of Aurora Nilsson’s life. While much of it is quite faithful to her own story in Flykten från harem, the narrator’s perspective is radically different. Whereas Nilsson writes of abuse, defencelessness, and an alien culture that arouses fear and loathing in her, Löfström describes transcendent love in a landscape so beautiful that it makes the reader’s head spin. And while she is her own advocate, Löfström pleads men’s cause. Flykten från harem foreshadows Not Without My Daughter (1989) by Betty Mahmoody and William Hoffer.

Despite the fact that Mahmoody is an American and of a different social class, her story is remarkably similar in terms of content, detail, and style. Upon returning to their native countries, the husbands of both women are transformed from civilised, devoted partners to abhorrent, oppressive monsters. Both Nilsson and Mahmoody are locked up and abused, but fight with every ounce of their strength – first to make their captivity more tolerable – their pitched battle with the filth that surrounds them assumes metaphysical proportions – and then to escape. The final, suspenseful scenes take both women over high mountains towards the freedom that beckons to them from Europe.

“After obtaining my degree, I returned to Stockholm, was admitted to the Karolinska Institute, and took part in the big demonstration for women’s suffrage on 20 April 1902”, Gerda Kjellberg (1881-1972) writes in her autobiography Hänt och sant (1951; True Events). Her struggle for education typically accompanied her commitment to the feminist cause. She earned her upper secondary degree after a lot of hemming and hawing, tremendous effort, and personal loans. She pursued a medical education and became the first woman specialist in venereal diseases. Her father compiled a list of possible careers following her confirmation: maid, steamboat stewardess, hospital orderly, nurse, teacher, doctor.

The right to obtain an upper secondary degree that Swedish women won in 1870 offered only limited opportunities for higher education. As her father’s list indicates, teaching and medical careers were among the few options. Both professions were vital to the women’s struggle, and a sense of social indignation guided Kjellberg’s choice. A trip to Paris at the age of sixteen opened her eyes to the social degradation of women. Seeing prostitutes and their plight, she decided: “I want to help cure society of this scourge.” The Karolinska Institute brought her into contact with many women who had made the same commitment: “The pioneers were Karolina Widerström, Ellen Sandelin, Hedda Andersson, Maria Folkeson, Sofia Holmgren, and several others.”

“In the decades around the turn of the century, two issues were in the foreground when it came to the relationship between men and women,” she wrote. “One was the population question, while the other was the struggle against venereal disease and the associated regulation of prostitution.”

Glimtar ur mitt liv som läkare (1963; Glimpses into My Life as a Doctor) by Ada Nilsson (1872-1964) focuses on those very issues. She travelled the country to educate the public about sexual matters. The autobiographies of other women portray her as strong, self-sacrificing, and devoted to her cause. “She fought tirelessly to abolish the vagrancy act and the regulation of prostitution, to disseminate sexual information, and to provide public assistance for mothers,” writes Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt (1888-1982) – who waged an equally impressive battle against the suffering of refugees around the world – in her autobiography Den värld jag mött (1967; The World I Have Seen): “I was endlessly amazed that she had the energy to carry on. Namby-pamby women were the one thing Ada had trouble accepting – combative, rebellious, misled, even indoctrinated, all that she could celebrate or understand – anything but namby-pamby.”

“My life has always been overflowing with people, so the title of this volume might seem paradoxical,” Ellen von Platen writes in her autobiography Ensam genom livet (1939; Alone through Life). “But that is only on the surface. Being alone is not proportional to the number of people you have met; the path of the loner wends its way through the multitudes. But I could also answer that question in a more straightforward way. A woman who has never had a husband and children, and thus has lacked a home in the most profound sense of the word, is bound to feel alone.”

The autobiographies of the pioneers tell their own story of the struggle against sexual exploitation and for education as well as financial and legal equality. Whereas prostitution and suffrage long remained in the limelight, peace was an increasingly urgent matter a few years after the turn of the century. Feminism and peace conflated into one issue, and opposition to war channelled the energies of more and more women.

Reading Bertha von Suttner’s Die Waffen nieder! (1889; Eng. tr. Ground Arms – The Story of a Life) as a child turned me into a lifelong pacifist,” writes Kjellberg in Hänt och sant. “The only thing that has changed somewhat through the years was my view of various peace organisations.” She was a Swedish delegate to the 1916 International Peace Congress at The Hague, and her autobiography offers a lively account not only of the event itself, but of the delegation as it wound its way through wartime Germany in boxcars.

“Our circles were only vaguely aware of feminist ideas,” right-wing politician and landowner Eva Fröberg writes in Hemma i Sörmland och ute i världen (1945; Home in Sörmland and Out in the World). “But it bothered me no end that workers in Husby had the right to vote but not I […]. It was humiliating to simply stand by and watch the simplest of simpletons walk up to the polling booth.”

The outbreak of World War I was a turning point for the feminist and pacifist cause. Optimism turned to despair. The name of the chapter about this period in Vad vi tänkte (1941; What We Thought) by Anna Lindhagen (1870-1941) is “Disillusionment”. The autobiography exudes a sense of commitment. Lindhagen, who was also a Swedish delegate at The Hague, saw the cause of peace as integral to her social activism. Like many others, she was heavily engaged in both political struggle and relief efforts during the war.

Anna Lindhagen’s autobiography Vad vi tänkte (1941; What We Thought) recounts a life totally devoted to the cause; she constantly shows up in the autobiographies of other women as a source of inspiration: Amelie Posse calls her “a whirlwind of energy” in Åtskilligt kan nu sägas. “She never wearied of passionate protests against the coalition government’s ‘ladylike’ caution and unforgivable appeasement… Day or night, she gave her all. Until her dying breath, she wore herself out for the countless causes and organisations she had launched to help refugees who often took advantage of her benevolence, and carrying on the last great struggle against the forces of darkness.”

“Characteristic of the word idealism at the beginning of the century,” Björkman-Goldschmidt writes in her autobiography Jag minns det som igår (1962; I Remember It Like Yesterday), “was a fresh breeze of will to action, of an unshakable belief in the liberating power of education, that fluttered towards an ever-brighter horizon. Two world wars had not yet punctured our illusions.”

As a young woman, she threw herself into the arduous relief effort that followed World War I. She went to Russia with the Red Cross disaster relief team and met her future husband among the prisoners of war there. She directed the Viennese branch of Save the Children in 1919-1924 and remained deeply involved in social work and anti-Nazi activities until she and her husband fled to Sweden in 1938. Once there, she again joined non-profit relief efforts. After helping the Fund for Finnish Relief, she turned her energies to the reception of refugees during the war.

Sigmund Freud was one of the many people whom Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt met in Vienna between the wars. He lived right around the corner, and they ran into each other all the time. “With his turned-down starched collar and grizzled beard, Freud looked like a mild-mannered senior master at a secondary grammar school in a small Swedish town”, she wrote in Det var i Wien (1944; It Was in Vienna). She changed her tune when she subsequently met him in private:

“That was during the lean years in Vienna; the Swedish relief effort was being discussed, the almost insurmountable obstacles it faced, its many advantages and disadvantages, and what it was that humanity most needed – sympathy, socialism, or religion. The disagreements were legion, and debate was intense. I sat there and gazed at Freud; no longer did I think he had a commonplace appearance. I had caught sight of his high, handsome, and arched forehead, his eyes that looked both wise and kind.”

Her five-volume autobiography has a personal depth that carries it far beyond pure documentary. The six autobiographical works of Mia Leche Löfgren (1878-1966) are even more remarkable in that respect. Active in the early peace movement, she drew inspiration from a speech by Ellen Key. “At the height of the union crisis, Key raised her calm, wise voice in a passionate entreaty for peace. Delivered in the auditorium of the old Academy of Science, it was the first pacifist speech I had ever heard, and it left an indelible impression on me.

My debut as a journalist stemmed from the agitated mood of the capital.” Witnessing the virtual lynching of a private on Strandvägen Avenue because he had not properly saluted a passing lieutenant, she was so filled with rage that she rushed home and wrote her first anti-military article.

Hård tid (1946; Hard Times) and Ideal och människor (1952; Ideals and People) also focus on her public deeds. But her later works, above all Upplevt (1958; Experienced), in which her highly dramatic personal life assumes centre stage, lend true intensity to her material. Her own struggles mesh uniquely with her battle for a more humanitarian world. A painful divorce that deprives her of her children provides her with first-hand insight into women’s lack of legal protections.

Upplevt (1959; Experienced) by Mia Leche Löfgren devotes a major section to the autobiography of her good friend Marika Stiernstedt:

“I had a more lively relationship with her than just about anyone else, and we wrote endless letters when we couldn’t get together. Imagine my shock when I read her great confession, Kring ett äktenskap (1953; About a Marriage) shortly before her death. Had the big angular living room in which Marika sat every evening with her flower embroidery really been a battlefield between two people who were too fond of each other to separate and too different to live in peace? Reading her remarkable book put a lot of things in a whole new light.”

Löfgren was deeply involved in assistance efforts for refugees in the interwar period and for the victims of World War II. The resistance to Nazism brought women together once again, and Åtskilligt kan nu sägas (1949; A Good Deal to Say) by Amelie Posse (1884-1957) was something of a group portrait of feminist pioneers.

“Like all liberal women of the day, I was an all-round feminist,” Löfgren writes, “but Ann-Margret Holmgren, Karolina Widerström, Gerda Hallberg, Lydia Wahlström, Anna Bugge-Wicksell, Gulli Petrini, Signe Bergman, and other pioneering suffragettes were from a somewhat earlier generation. If I was part of that movement, it was primarily for the cause of pacifism.” As was the case with so many other women of the period, Löfgren laboured in the service of peace for much of her life.

The book was the magnificent eighth part of Posse’s peculiar but cohesive ten-volume autobiography, the conclusion of which was published posthumously by Barbro Alving. The first volume, which was published in 1931, was about her marriage with artist Oki Brazda, while the following three proceeded in chronological order. I begynnelsen vår ljuset (1940; Eng. tr. In the Beginning Was the Light) and Kring kunskapens träd (1946; Around the Tree of Knowledge) return to the Lund of her youth, but World War II forced her not only to flee her home in Czechoslovakia, but to resume her narrative of the present.

Åtskilligt kan nu sägas is a harrowing document of her flight from a devastated country, as well as her efforts on behalf of refugees and against the Nazis. Returning to Sweden in 1938, she took it upon herself to inform society and government – both of which were reluctant to listen – of the Nazi atrocities. But she did not stop there. She put together a private refugee programme, which expanded in 1940 to include the Tuesday Club, a rallying point for the anti-Nazi movement in Sweden. Some of the same names re-emerged: Anna Lindhagen, Lydia Wahlström, Mia Leche Löfgren, Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt, Marika Stiernstedt, and many others. Once more they enrolled in the struggle for peace, humanism, and a more caring society. Again they raised the banner of democracy, gave everything they had, attended meetings, and travelled the country to impart wisdom and inspiration. Posse does not simply write about her own accomplishments. Like the other female autobiographers of the time, she describes the various activists and their efforts.

Translated by Ken Schubert