In 1892, the Norwegian Modern Breakthrough writer Alvilde Prydz (1846-1922) published the novel Mennesker (People). She introduces us to her central character, Helene Ørn, who has just started a job as a teacher in an outlying mountain district. She walks into a Christian meeting house in order to see Knud Gripp, a man she had met at an earlier point in her life and had never since forgotten. But the meeting is uncomfortable and chilling. An odious male figure stands between the two. His body is that of a subterranean creature, and he smells foul. His mouth, however, is sensual, wide, and moist, and the look he gives her signals that they have some link, that they share a secret. At the same time, Helene Ørn is held in the hard gaze of the man she has come to see, but there is no help to be had.

“It had been windy and raining; hot from the brisk walk, she took off her dripping-wet capote coat and remained standing by the door.

“A man at the front got up and offered her his chair; it was Knud Gripp. A peculiar sensation ran through her; exactly this had happened once before, the evening when she came into the chapel and he stood up and offered her his chair – had it but been, like that time, he who now mounted the rostrum!

“She looked up. A small hunch-backed person with sharply drooping shoulders was standing there. He stayed where he was, and raised his eyebrows up and down, but his eyes blinked with a secretive expression. From his wide mouth with its large, moist lips, half open, ready for the stream of words, came a pungent smell of chewing tobacco.

“Helene wrapped herself tighter in her coat. A sensation of disgust swept over her. She wished she had stayed down by the door, – and she felt a pair of hard eyes fixed upon her.”

Alvilde Prydz: Mennesker (1892; People)

Mennesker, and its sequel Drøm (1893; Dream), is in many ways a typical work of the Norwegian Modern Breakthrough, painting an ironic picture of the provincial Norwegian official class. Traditional values are on the brink of collapse, which makes for social and personal crises. The crisis was particularly manifest in women’s lives; those who live according to the old norms are unhappy, as are those who try to lead a modern life. Central to the tale is the love affair between Helene Ørn and Knud Gripp. Helene Ørn is described as a woman with a strongly independent streak and a sense of sexual awareness. The text emphasises the intense erotic attraction she feels in relation to Knud Gripp. She desires and wins the stern, yet mother-fixated man.

She does not ever recall or refer to the image of the odious male figure, but the reader does not forget it so easily. The scene in the Christian meeting house is full of bad omens, which are largely borne out by the story. The marriage between Helene and Knud is described as intensely problematic. Their child dies, and Helene herself comes close to death before reaching the stage where her husband gives her the acceptance and respect as an equal that she needs in order to live. The story confirms the identity of the male figure Helene met in the meeting house: he is a portrait of male sexual instinct, in a threatening and monstrous rendering. Reading other novels written by women during this period, it becomes apparent that this is a commonly recurring figure.

Problematic Modernity

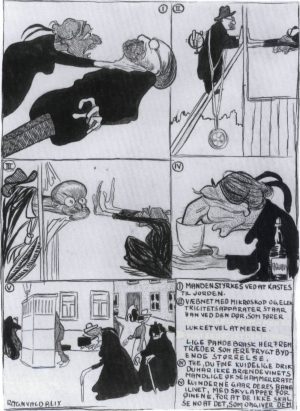

The figure appears again in the novel Kvinder (1889; Women), published in Christiania with the secondary title Et stykke udviklingshistorie (A Story of Development). The title page states “Christiania novel”. The author, Anna Munch (1856-1932), lived a modern, insecure existence in the arts world, by her own account often on the breadline, but she continued writing until she was sixty years old.

This, her first published novel, is a work of fiction with a purpose, almost didactic. It addresses some of the central themes in the literature of the Modern Breakthrough: conventionalism and confinement in the traditional society, new norms and the new, unsettled relationship between the sexes. The story is about three sisters living in Christiania (modern-day Oslo); their father is a head teacher, and they are all, in each her way, in the process of leaving his house. Their mother is dead, and they have hitherto lived in comparative freedom. Bergljot is the most rebellious. She looks on in indignation as her older sisters contract conventional marriages: the one as a loyal clergyman’s wife, with the prospect of a strenuous life; the other simply in order to be married at all and be able to keep house and entertain guests.

Bergljot wants to be free and modern. She discusses the women’s cause with her sisters and her friends, and embarks on a love affair with an artist, a painter named Nordby. She falls pregnant; when she goes to her lover in his studio with the intention of telling him, he is a changed man. Again, the picture emerges of the odious and chilling man:

“‘Why did you not come, – do you hear, what was wrong?’ he kept on.

“She could not answer. A sense of disgust swept over her, disgust for sitting here holding his hand, for being here at all, – a strong urge to stand up – at all events to go as far away from him as possible if she was going to speak […].”

After this scene Bergljot realises that her relationship with the painter has been a mistake. She tells neither her lover nor anyone else about her pregnancy; nor does she tell them that she is going to emigrate to America. A friend, Gunnar, who although realising what has been going on remains fond of her, follows her on her journey.

Literary critic Mathilde Schjøtt (1844-1926), who wrote about Kvinder in the women’s magazine Nylænde (New Land; journal of Norsk Kvinnesaksforening, Norwegian Society for Women’s Rights), immediately identified it as a modern novel of the women’s cause. It was “written with the pen of strong conviction, fervent, intense, as if saturated by colour”. In keeping with the feminist cause, the novel was a “warning against the bohemian leaning” – with the proviso that it nevertheless betrayed “a degree of bohemian affinity”, which is undoubtedly a correct analysis. The setting of bourgeois officialdom is depicted as dreary and conventional, while the bohemian life has a lively and enticing ambiance. The friend and accomplice, Gunnar, acts sensibly, but he is not presented as being attractive. And the end of the story seems to vindicate the heroine: she takes the radical step of endeavouring to live alone with her child. What Mathilde Schjøtt did not spot, however, is that the turning point in the novel occurs at the moment Bergljot feels a sense of disgust in relation to Nordby. The novel thus rebuffs bohemian life – and male instinct.

Dignity versus Sensuality

Allegations of ‘bohemian affinity’ were unlikely to be raised against the first novel by Drude Krog Janson (1846-1934), En ung pige (1887; A Young Woman). The heroine is already in America, more specifically in the Scandinavian emigrant quarter in Minneapolis, where the author herself lived. Drude Krog Janson was Danish-born, married to a Norwegian, but later divorced.

In this story, men’s vitality and desire is unmistakably coupled with violent behaviour and abuse of power. The central character, Astrid, has come to America along with her bankrupt father and her younger brothers. She keeps house for her father, a man drawn into a drunken masculine milieu. She is expected to contract a financially fortuitous marriage, and does indeed get engaged to a rich and handsome man. As he becomes more and more sexually insistent, his sensuality is described with growing revulsion.

The turning point comes when Astrid meets the king of poets, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, who is on tour in America and visiting the Norwegian immigrants. In his omniscience, Bjørnson exposes her fiancé as an untrustworthy seducer of women. He encourages her to find her own way in life, which she finally manages to do – with help from a woman doctor who gives her shelter. Astrid becomes a pastor, and looks forward to living her life safely spared from male sexual demands.

The three novels are from different settings and of varying literary quality, but have some conspicuous features in common. They have ‘novel-like’ and partly Romantic plots with many melodramatic elements. In this respect they are typical of the nineteenth-century novel. The plot can be summed up by the formula dignity versus sensuality. This plot occurs in countless novels and long stories written by female authors of the period. It is almost a ‘primordial narrative’, an archetypal female story: the female central character feels cooped up in the conventional life she must lead within the bourgeois class of officials. She dreams of a different, freer, and richer existence. And then she encounters the modern way of life, among artists or in the streetlife of the ‘city’, which in Christiania essentially meant just the one street, Karl Johans gate, the main thoroughfare. She is seduced, tempted, or persuaded to commit herself to one man. However, in the end she relinquishes love and marriage and chooses independence – a choice underpinned by experience of male lust as frightening and violent. There is, however, often a male accomplice in the story, a ‘pure’ man who ensures that the project with regard to independence can be fulfilled.

In all their apparent simplicity, these stories are paradoxical and unexpected. They tell of deep conflict between the sexes, between the world as lived by women and by men, between their reason and their desire. While men of the Modern Breakthrough write enthusiastically about a new relationship between the sexes, the women depict their encounter with male desire as a problematic experience imbued with anxiety. Even though the narratives have modern expectations in the form of women’s stories of development, there is also a constantly flagged message telling of resistance to the ‘modern’, at least as defined in its masculine form.

Departure and Expectation

The problematic and almost provocative aspect of the stories is not simply that they contradict our handed-down expectations of ‘modern’ realism. They apparently also contradict the purely historical role played by the women of the Modern Breakthrough in Norway. As in the other Scandinavian countries, the discussion about femininity had been of key importance to male writers and intellectuals of the radical literary movement from its very beginning. Norway, however, was a rather special case in that a number of women became significant, indeed central co-players in the movement – which contributed to the forging of an alliance between the women and the leading male intellectuals. This also meant that the women’s views on literature and morality made their mark on the dominant viewpoint in the Norwegian Breakthrough movement.

Moreover, it was feminism that ushered the ‘modern’ ideas into Norway. In the early 1870s the leading Norwegian liberals were largely dismissive or sceptical of the radical programme launched by Georg Brandes in Denmark. Brandes’s anti-clerical viewpoint was not looked upon favourably, and his literary agenda was deemed far too radical. Instead, attention was turned to contact with the milieu around the Grundtvigian and anti-Brandesian Copenhagen journal For Idé og Virkelighed (For Idea and Reality). When it came to women’s issues, however, Brandes’s views met with sympathy. In 1869 he published a Danish translation of John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women, penning a foreword, and triggering a debate in Norwegian newspapers and journals. After a conservative ‘woman’s voice’ had been heard in the newspaper Morgenbladet, Camilla Collett took to her pen in the same newspaper, signing herself “CC”. Her article was headlined “Emancipation”; she defended Mill’s ideas and attacked the institution of marriage forged merely to provide for the woman.

She was joined in her campaign by the painter Aasta Hansteen (1824-1908), who was to become one of Norway’s most aggressive and insistent feminist writers. In the daily newspaper Dagbladet, Hansteen published four articles, signed “By a woman”, in which she roundly criticised the view of women promoted by Church and conservatives. She soon followed this up with a series of articles about feminism and theology, published in the Grundtvigian Nordisk Maanedskrift for folkelig og kristelig Oplysning (Nordic Monthly Journal for National and Christian Enlightenment), which she signed with her full name – something which was still unheard of. The articles formed the foundation for her feminist theological work Kvinden skabt i Guds billede (1878; Woman Created in God’s Image).

Several male critics also took part in the debate. Critic and author Kristian Elster the Elder presented Mill’s book in five articles published in Norsk Folkeblad (Norwegian People’s Newspaper) in 1870, characterising it as “the most scrupulous, most insightful, most fervent and eloquent expression” of “the common movement that has now for more than a score of years, with ever increasing strength, asserted itself to advance woman’s rights and woman’s freedom in family, society, and state.”

Realism and Criticism of Marriage

Another contribution to this first debate on the subject of feminism was a slim work called Venindernes Samtale om Kvindernes Underkuelse (1871; Lady Friends’ Discourse on the Subjugation of Women), which was published by the Aschehoug publishing house in Christiania. The work was originally published anonymously, but its author was later revealed to have been Mathilde Schjøtt. The text is a dramatised presentation of Mill’s viewpoints in the form of a long, ‘erudite’ discussion between a group of female friends. The writer allows some protest against the radical ideas in Mill’s book, but the debate concludes in his favour. Along the way, there is many a critical remark vis-à-vis women’s lack of legal rights in marriage.

A literary theme also emerges during the course of the discussion. One of the friends refers to the French woman George Sand as being a typical female, and thereby bad, author. There is some sympathy in the group for this view, but then the mood changes – they reach the conclusion that George Sand is able to express female experience in a way that no male writer could. This element of the discussion illustrates the level of importance that women’s culture in the more affluent strata of society now attributed to works of fiction.

As was the case in the rest of Europe, women from the upper middle class and from the class of administrative officials were the key readership of the modern novels; they were also heavily represented among translators of foreign-language novels. These were women who worked in the private and public subscription libraries and reading societies, and who were in some measure also commercial dealers.

During the 1870s the Kvindelige Læseforeninger (Women’s Reading Associations) also spread to Norway; one of the first to be set up was in Christiania in 1874. This provoked complaint from conservative men, but one such protestation was slyly countered by a woman writing in the conservative newspaper Morgenbladet. She endeavoured to present the reading associations as harmless, arguing that even though there might possibly be some concern about the steady growth in women’s reading of fantasy novels and the like, a splendid opportunity had now arisen to supervise women’s reading habits – the reading associations would thus benefit, not harm, family life. The letter in the newspaper was published anonymously, but it later came to light that the writer was Vilhelmine Ullmann (1816-1915), Mathilde Schjøtt’s aunt. Her personal development contradicts the argumentation in Morgenbladet: having divorced and moved from Trondheim, she took employment in Christiania, and in the 1880s she went on to become a committed literary critic.

The women writers’ compass pointed towards the themes and style of realism. The social and geographic horizon was expanded. The work and life of people living in ‘remote’ or little known districts of Norway became a common theme, and the depictions of their circumstances opened up for social criticism, also of the traditional marriage. The novels of formation and the Bildungsroman reveal the women’s newly-awakened expectations of greater social and individual freedom. The widely-travelled and very productive Elisabeth Schøyen (1852-1934) wrote several novels about the lives of women, among them Kamilla (1873), Svanhild (1876), and Et Egteskab (1878; A Marriage); she also wrote a novel about the new, intellectual man, Ragnvald: eller Folkehøiskolelæreren (1873; Ragnvald, or The Schoolmaster). In 1872, under the pseudonym “Tante Dorthe” (Aunt Dorthe), the newspaper Morgenbladet had published Elise Aubert’s (1837-1909) thoughts on the upbringing of girls and the educational opportunities for women. Her first published collection of short stories, Hjemmefra. Fortællinger for de Unge (1878; Away from Home. Tales for Young People), described life and lore in Finnmark as seen from the perspective of a young newcomer, the pastor’s daughter. The subsequent novels from her hand were novels of female formation, Kirsten. En Fortælling (1880; Kirsten. A Tale) and Dagny (1882). She was an active writer until the year of her death, 1909. Petra Hauan (?-1883) did not have so long a life. She wrote serialised novels for newspapers in Trondheim and Bergen, and published, among other works, Ingeborg og Thore: et Livsbillede fra Landet (1877; Ingeborg and Thore: A Portrait of Rural Life) and, under the pseudonym “Lulla”, En Dagsjauer familie (1879; A Day-Labourer Family).

“Lauren’s cool, pale, but immortal radiance”

One of the most popular women writers was Marie Colban (1814-1884). Her first published work was the novella Lærerinden, en Skizze (1869; The Schoolmistress, a Sketch), and she went on to publish Tre Noveller: Tilegnet de norske Kvinder (1873; Three Stories, Dedicated to the Women of Norway), Tre nye noveller (1875; Three New Stories), and, among other works, the story Jeg lever (1877; I Live). By the Norwegian standards of the day, Marie Colban took the unusual step of spending her long widowhood abroad; from 1856 she lived in Paris, where she supported herself by writing political and literary ‘correspondence’ for Norwegian newspapers and journals. Her books were published by Gyldendal in Copenhagen, which was highly prestigious. Many of her short stories take up the theme of the terms and conditions for women’s lives and marriages. The short story “I det høie Nord” (In the Far North), from Tre Noveller, could almost be called a novel; it depicts a woman’s powerlessness and distress, married to a man who for long periods takes up with an old female friend of the family as his confidante. The woman leaves her husband in protest, but the story ends with reconciliation for the couple.

Colban was no ‘Breakthrough writer’, but she pre-empted many of the features found in the novels of women’s formation and Bildungsroman in the 1880s and 1890s; this is particularly true of her last novel, Thyra (1882). The style of writing, full of oratorical effect and floridly Romantic as it is, can be said to be past its sell-by date. The plot, on the other hand, is readable. The novel deals with a strong and independent woman who falls in love, but ends up having to renounce love. The heroine has to help the man in making his choice: will he take her or her rival, who happens to be her younger foster sister? Hearing an alluring woman’s voice singing in the forest, he is unable to keep his promise to the heroine; she ends up devoting her life to scholarship. The message is expressed in the final passage of the novel: “The burning, swiftly waning glow of the roses was replaced by Lauren’s cool, pale, but immortal radiance.”

Behind this Romantic paraphrase there is a clear appeal to the woman that she should reject sensual pleasure and instead turn her attention to bringing her intellectual faculties to fruition. At the same time, however, the story comes up with a doppelgänger or mistaken-identity motif that makes it difficult to distinguish the heroine from her rival. It would seem that it is not the rival, but the heroine herself, who is doing the enticing with (siren) song in the forest. By this means, the structure instils doubt as to the actual identity of the desiring and sensual woman. Female desire is seemingly absent, but is manifested in the text via doubling and disguised forms. And thus is the edifying message of “Lauren’s cool, pale, but immortal radiance” undermined.

This feature is to be found in many of the stories written by women of the period. The central character in Alvilde Prydz’s novel Gunvor Thorsdatter til Hœrø (1896) is indeed a ‘heroine’, seen at the time as an exemplary new type of woman, strong, independent, and bold, whereas the men are presented as weak and yielding. But even though their cowardice and deceit cause Gunvor to forgo sensual love, the novel – like Colban’s – is full of images and symbols linking the heroine with the ‘drive-cathected’ woman.

In the work of Elise Aubert, Drude Krog Janson, and others, the depiction of sexuality also clearly serves to illustrate the obstacles and temptations encountered by the heroine on the road towards dignity and self-respect, but these temptations are often presented so ‘seductively’ that the explicit message is jeopardized. This was the suspicion underlying Mathilde Schjøtt’s critique of Anna Munch’s Kvinder.

“Woman of the Future”

One person who was less than enamoured of Marie Colban’s message was Camilla Collett. She wrote a crushing critique of “I det høie Nord”, accusing the author of “praising the powerful”. Although the story might have been intended as a deterrent, Camille Collett did not think it functioned as such – rather, it accepted woman’s perpetual self-sacrifice. This stern judgement was typical of Camilla Collett.

Camilla Collett would not accept women being portrayed as passive and servile. As a rule, it was the male writers’ image of women that she took to task, but women writers such as Marie Colban were also upbraided.

The critique of Colban was included in the essay collection Fra de Stummes Leir (From the Camp of the Mute), which Collett published in 1877. This collection is, quite rightly, considered to be one of the first Norwegian Modern Breakthrough works – and it located Collett in the modern camp. One of the most programmatic essays in the collection is her discussion of the Danish writer J. P. Jacobsen’s debut novel Fru Marie Grubbe (1876; Eng. tr. Marie Grubbe. A Lady of the Seventeenth Century).

Camilla Collett’s thoughts on Fru Marie Grubbe were originally published in Ny illustreret Tidende (New Illustrated Times), but were later worked into her long essay “Kvinden i Litteraturen” (1877; Women in Literature, in From the Camp of the Mute).

The essay declares the eponymous heroine of the novel to be the woman of the future:

“Marie Grubbe is the woman of the future, the near future. The transitional, the woman finally shaken into consciousness of herself and her position. She has not yet arrived, this woman; she is still dozing; she sees nothing; she is going nowhere; wants to see and know nothing. She must simply be what she has been for centuries, at hand with her inexhaustible store of love, her always presumed readiness to sacrifice, her bottomless forbearance […].”

This is a quite sensational pronouncement considering that, at the time she made it, Camilla Collett was a – for the times – elderly woman who had published her principal literary work, Amtmandens Døttre (1854-55; The District Governor’s Daughters), some twenty years previously. She herself considered her most significant intellectual anchorage to be in the Intelligenskrets of the1840s, a group of intellectuals who wanted to modernise Norway. And now she was standing up for one of the young, radical writers. In J. P. Jacobsen she had found an authentic depiction of reality and a symbolic presentation of the new world, the vision of a woman who would no longer sacrifice herself: “Marie Grubbe’s well of forbearance has sprung a leak […] Her readiness to sacrifice requires guarantees.”

The Starting Point, 1877

The year in which Fra de Stummes Leir was published was also the starting point for the radical literary movement in Norway. In the autumn of 1877, the writer Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson addressed Det Norske Studentersamfundet (Norwegian Students’ Society) in Christiania, calling his subject “At være i Sandhed” (Live in Truth). Purely in terms of content, the lecture had but little substance, but it was a masterpiece of rhetoric and taken as being the clear signal of a break. Bjørnson now left the moderate, Grundtvigian liberal standpoint and went over to ‘infidel’ radicalism.

The background to this break was, however, familiar to ‘everyone’: in the autumn of 1876, Georg Brandes had been the focus of a mighty controversy in Christiania. He had been invited to come and speak about his Kierkegaard book and, being an academic, he was meant to have given a lecture in the auditorium at the university; the conservative management at the university had other ideas and refused him admittance, thus mobilising the liberals to battle. The upshot of it all was that he was invited, with great support, to speak in Studentersamfundet.

Bjørnson’s ‘conversion’ was the starting shot for a serious transformation of attitudes in the Norwegian intellectual liberal milieu. Historian Johan Ernst Sars had long been an adherent of modern European currents in the natural and social sciences, but he wanted to introduce the new disciplines in such a way as to benefit a Norwegian independence movement. With Bjørnson’s support he now launched Nyt norsk Tidsskrift (New Norwegian Periodical), co-editing it with Olav Skavlan, professor of literature. The periodical attracted a group of radical intellectuals who were also involved with the newspaper affiliated to the Liberal party (Venstre), Dagbladet, and other political and literary projects.

At the same time, imaginative literature changed tack, corroborating the radical authors’ support for the ‘woman of the future’. Bjørnson’s first Modern Breakthrough work, his novel Magnhild (1877), could be described as a Norwegian Madame Bovary in taking the woman’s disquiet in her marriage as its central theme. Two years later he presented a play, Leonarda, similarly defending the woman’s right to leave her marriage. This was also the year in which Henrik Ibsen’s major play on just this subject, Et Dukkehjem (1879; A Doll’s House), was premiered. The male writers tabled women’s constraints as being one of the most serious charges against the conventional social structure, at the same time as ‘woman’ became the symbol of new departures and the modern world.

“Shatter all fetters”

For the first few years after 1877, Norwegian society was predominantly conservative, and the circle around Sars and Bjørnson continued to be in the minority in the Liberal party. The lack of support was apparent from, for example, Nyt norsk Tidsskrift being obliged to cease publication after two years. The climate was so harsh that both Bjørnson and Ibsen took themselves abroad, Ibsen for an extended period of time.

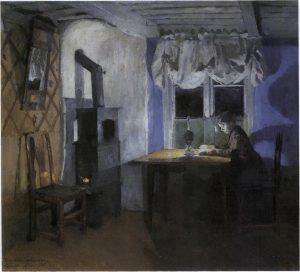

One of the people to feel this social opposition at first hand, divorced mother-of-two Amalie Müller, née Alver, later married name Skram, had read Bjørnson’s Magnhild and taken the courage to break out of her unhappy marriage. She had moved from her hometown of Bergen and was living with her sons at her brother’s home in the small town of Fredrikshald (today Halden). Besides writing literary reviews, she based her livelihood on giving private language classes. Her reviews were either published anonymously or signed “ie”. The first one with which we are familiar is about Fru Marie Grubbe and was published in the newspaper Bergens Tidende (Bergen Times) in 1877. The same newspaper later published her reviews of Elisabeth Schøyen’s novel Et Egteskab and a number of foreign works. In 1878 and 1879 she reviewed a total of fourteen books in the Fredrikshald newspaper Smaalenes Amtstidende.

In February 1878 she sent a review of Bjørnson’s drama Kongen (1877; The King) to the writer himself. In her accompanying letter she disguised her identity as “Hr. A.M.”. “Who are you?” asked Bjørnson in his first reply. He arranged – although with some delay – for the article to be printed in the newspaper Oplandenes Avis. In his next letter he was getting closer to revealing that he knew who she was: “Are you not a lady?” Not long afterwards his conjecture was confirmed, and he invited her to visit him at his home in Gausdal, Aulestad.

Even though it was an honour and a pleasure to be invited to Aulestad, a visit was not without its problems. Acquaintance with the ‘infidel’ Bjørnson did not go unnoticed in the small community. As late as 1881 such association was still seen as scandalous. Amalie Müller told Bjørnson’s wife Karoline about the reaction:

“Since my ‘radical’ and ‘infidel’ stance, and I say it freely, my ‘worship’ of Bjørnson, as it is called, became known here in the town, I have, can you imagine, not been able to attract a single pupil, in spite of being good at advertising myself. I am, in a way, excommunicated.”

An expectation had thereby been created; a seemingly inexorable development had been set in motion. When Amalie Skram reviewed Et Dukkehjem in Dagbladet in January 1880, she wrote that readers should not “underestimate the problems”. What was approaching was nothing less than going beyond all walls and “shattering” all fetters: “This rendition of life stands amongst us as a sign and a warning and a judgement. When woman awakens to full consciousness of her dignity as a human being, when she rightly perceives all the injustice that has been used against her through the ages, then she will take arms against the one she was assumed to assist, and she will shatter all fetters, go beyond all walls that society and the institutional authorities have erected around her.”

Female Critics

Awareness that a break was about to happen also coloured an article on “Bjørnson’s Last Works”, published in Nordisk Tidskrift (Nordic Journal) in 1879. The signature “D.d.” told the initiated that the writer was a woman: Mathilde Schjøtt. To the readers’ surprise, it was a thorough and well-informed article in which the writer also stood up for propaganda writing: “It is an aesthetic dogma that a work in which there is propaganda is not a literary work. But one of the difficulties with the great writers is that they compel the aestheticians to rewrite their aesthetics. Take Leonarda. It is sheer love, poetry, and enchantment, and yet how full of propaganda.”

Mathilde Schjøtt probably found it easier than Amalie Skram to line up with the radicals. She came from old and good public officer stock with links to the leading liberal elite. Her father was the government lawyer Bernard Dunker, a close friend and ally of Bjørnson and Sars. Her grandmother was memoirist Conradine Dunker. But of course Mathilde Schjøtt had not had an academic education, and her family situation made it difficult for her to take the step out into the public literary arena. She had spent a large part of her youth in Copenhagen, in the home of writer Christian Winther, and she had later trained as a language teacher, studying in Brussels and Paris.

Back in Christiania, she taught French on a course for governesses while pursuing her own studies. She then became a professor’s wife, had four children and a large household to manage. In the 1870s, in addition to Venindernes Samtale om Kvindernes Underkuelse, she published a few literary texts (anonymously), but it was not until 1877 that she ventured out into the open – in her own name. This was signed under an article taking sharp issue with the critic Henrik Jæger because he had written what she considered to be a distorting article about Camilla Collett seen in a historical literary perspective.

A third woman writer emerged alongside Amalie Müller and Mathilde Schjøtt: Danish-born Margrete Vullum (1846-1918). She had a tough start in the Christiania literary milieu. She had moved to Norway in 1879 with her two children in order to marry Erik Vullum, who was a journalist and literary critic, and at the time editor of Dagbladet. Their relationship caused a scandal. As daughter of the Danish politician Orla Lehmann and widow of the well-known folk highschool educator Gotfred Rode, she did indeed have a solid social background, but ‘everyone’ knew that she had fallen in love with Erik Vullum while her husband had still been alive, and that she had lived on her own in Paris for nearly two years at the same time as Erik Vullum had been staying in the city. Erik Vullum, meanwhile, was very popular and much admired both for his talent and his looks, and he was considered to be Bjørnson’s heir apparent. And Bjørnson it was who took the new couple under his protective wing and let them celebrate their wedding at Aulestad.

Other women also ventured out into the public literary arena. Gina (Jørgine) Krog (1847-1916) was one of those who wrote about Et Dukkehjem when the play was published.

Gina Krog’s review of Ibsen’s Et Dukkehjem appeared in Aftenbladet (Evening Paper) and was signed “G – g”. The article title read:

“Wonderful things do not happen on an everyday basis”. Ibsen was given warm thanks on behalf of “we who have been waiting for this to be said […] for us, hearing you was like hearing the bells start ringing to announce the festivities after all the everyday days.”

Gina Krog originally worked as a teacher, but she gave this up in order to become a full-time politician for Venstre and to work on behalf of the women’s movement. In 1887 she became editor of the feminist magazine Nylænde, later taking on financial responsibility for the publication, which she ran until her death in 1916. Over the years, she wrote a large number of reviews and articles on literary subjects. She regularly wrote for the newspapers when Ibsen presented a new work; she never ceased to admire him, and she also saw to it that he was made an honorary member of Norsk Kvinnesaksforening (Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights).

Vilhelmine Ullmann, who had defended Kvindelig Læseforening (Women’s Reading Society) in 1874, showed in practice that this initiative had consequences beyond family preservation. Early in the 1880s she was writing reviews of works by, among others, Alexander Kielland. She later became a regular contributor to Nylænde – as did her daughter, Ragna Nielsen (1845-1924), an educationalist who became one of the leading feminists in Norway. Hanna Butenschøn (1851-1928), the wife of a civil official, made her debut as literary debater in 1886. She later wrote a number of major literary essays, particularly about Ibsen, and in 1890 she began publishing works of fiction under the pseudonym Helene Dickmar. Camilla Collett was still an active participant in the debate. She was often invited by newspaper editors to give her opinions on new literary publications, and she also sent in comments and reviews. Aasta Hansteen, on the other hand, left the public stage. She was an outsider, and her religious feminism met with little sympathy in the now atheistic Venstre (Liberal) climate.

Nor did it help her that she, too, had close family ties to the leading radical men. In 1880 she emigrated to America. When she returned home to Norway, some ten years later, the changes that had taken place meant that she could again write and campaign for her particular form of feminism.

Central Positions

Taking into account the great importance of literature in middle- and upper-class women’s culture, and also remembering how intensely the new literature focused on women, it is not so surprising that women started to write about literature. But it is rather more remarkable that some of them assumed key positions in the radical milieu.

Amalie Skram moved to Christiania in 1881. She got an apartment in the same building as the Schjøtt family, and for a while she had a hectic social and intellectual life. For a period she held a ‘salon’ for the liberal intellectuals in the capital. She wrote reviews and took on translation and editing jobs, not least for Bjørnson, and she continued to be a central figure in the radical milieu up until she married Erik Skram and moved to Danmark.

Margrete Vullum had send ‘correspondence’ to Dagbladet while she had lived in Paris. When she got back to Norway, the newspaper employed her as reviewer and art writer. She later also got the job of editing and publishing a series of small booklets and books, what was known as the Folkeskriftserien, with an informative and propagandist purpose, aimed at a broad readership.

Margrete Vullum tackled newspaper and book projects with true revolutionary zeal, which also involved financial sacrifices. She invested large sums both in Dagbladet and in the Folkeskriftserien. In the case of Dagbladet, at least, this was officially a loan, but she never got her money back. During the 1880s she went over to the newspaper Verdens Gang (The Way of the World), where she ended up mostly writing about visual art, but she also caused a sensation by writing an ardent defence, under her own name, of the painter and writer Christian Krohg’s novel Albertine (1886).

Mathilde Schjøtt was born into the innermost radical clique. Her husband, a professor of Greek literature, also occasionally reviewed literature for the liberal press. It was nonetheless an unprecedented move when she – a woman – was appointed principal critic on Nyt Tidsskrift (New Journal), launched in 1882. She was also literary consultant for Ernst Sars on the journal. Alongside this, she wrote some literary criticism for Dagbladet,and later for Verdens Gang. In addition, she became literature reviewer on Nylænde. She crowned her career in literary criticism by publishing a book on Kiellands Liv og Værk (1904; Kielland’s Life and Works).

When it comes to assessing the women’s significance, it must be remembered that in the early 1880s the Norwegian literary forum was not particularly well developed. The few serious publishing houses that did exist based their business on religious works and text books for schools.

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, who had achieved great success with his ‘peasant tales’, had split with the Norwegian publishers in the late 1850s, due to financial disagreements, and had since been published by Gyldendal in Copenhagen. He had persuaded Henrik Ibsen and other male writers to do the same, and it had become a matter of prestige for Norwegian writers to be published by Danish houses.

The reviewing system reflected the modest circumstances of the publishing sector. Reviewing was unsystematic. There was but a handful of regular writers on literary subjects and just a couple who tried to live from their writing. Up through the 1870s the press had expanded in connection with the formation of political parties, but most of the larger newspapers were in practice news agencies and advertising media. The liberal press did not have much financial muscle, and therefore mostly published small four-page newspapers. They paid their contributors badly, but had a comparatively large proportion of literary subject matter.

The women critics made regular contributions from the late 1870s onwards, and they made their mark with their clear-cut and assertive position on the new literature. They mostly wrote for the liberal newspapers. Their articles often seem to have been unsolicited submissions, which must have required a certain degree of boldness – possibly made easier by the fact that quite a few of the women had close family and social ties to the newspaper editors. On the whole they wrote anonymously or under well-camouflaged signatures, which was not in itself uncommon. Most literary reviews in newspapers were still unsigned, but the readers generally knew who bore the reviewers’ names, and also recognised their styles. In the women’s case, however, one key factor for their anonymity was that up until the mid-1880s it was considered improper, indeed shocking, for a woman to express an opinion in public. But the readers were used to finding out about the critics, and this was also the case as regards the female reviewers – and, anyway, more often than not the argumentation would reveal the pen of a woman.

Enthusiastic Defence

A contributory factor to the women’s status was possibly their enthusiastic coverage of the male authors. Today, some of their comments seem to be virtually uncritical admiration. This is particularly the case with Bjørnson.

Mathilde Schjøtt wrote that Bjørnson’s En Hanske (1883; A Gauntlet) had transformed the premise of aesthetic evaluation. Amalie Skram had already highlighted the break with Romanticism in her review of Fru Marie Grubbe (Bergens Tidende newspaper, 17 February 1877, unsigned):

“So now begins a new period of literature in Denmark, based on quite other assumptions than the previous, which slumbered in German Romanticism.”

Of Alexander Kielland’s novel Garman & Worse (1880) Amalie Skram wrote in Dagbladet (1 June 1880) that it was “the first and only one of its kind”. His works had brought “a breath of something new and unknown” into Norwegian literature:

“There is no other writer among us who has begun so earnestly the process of liberation from Romantic reminiscences.”

Admiration for Ibsen was just as great, but with him they kept a more respectful distance. The ‘code’ at the time was, however, far more impassioned than that with which we are familiar today. Bjørnson was particularly active in establishing an ardent and oratorical norm in public Norwegian debate. Furthermore, the women saw themselves as being involved in an almost invincible liberation movement.

Another key reason for male acknowledgement of the women was most likely that these women were so quick off the mark – they defined the necessity of making an aesthetic ‘break’, whereas the majority of male critics still had their reservations.

Truth and Reality

The need for a shift in aesthetics was often substantiated by means of an evolutionary optimism typical for the times. Realism was in harmony with the future. The zeitgeist demanded that literature should contribute to change by passing on a true picture of society.

For the first few years, this demand for a true depiction of life virtually escaped query, but it turned out that the truth required of literature by writers and critics alike was primarily the psychological truth. Society was ‘tabled for debate’, but in the main it was the fictional characters’ personal development, their psychological conflicts and dilemmas in the family and particularly in marriage as an institution that interested writers and critics. Aspects of society concerned with financial or class factors were given less space in the overall picture.

Consciousness of a new aesthetic departure also influenced the manner of evaluation. The reviewer now moved away from rule-oriented critique of genre and form in favour of appraising the social message of the literary work. In practice, reviews became more like discussions of the morality or ‘opinions’ in the texts, and as often as not it was the views expressed by the fictional characters that were being assessed.

The period was characterised by critique of opinion, which is also to be found in the analyses by the women critics. Amalie Skram was, however, an important exception. Alongside the Danish writer and critic Herman Bang, she is perhaps the most form-conscious reviewer among the adherents of realism and naturalism. From an early stage, her literary reviews reveal a future author’s preoccupation with the craft of writing. Like the other critics, she does indeed discuss the moral and philosophical motive underpinning a given work, but she takes her critique further into a discussion of how it is discharged in terms of aesthetics.

Mouthpiece

The self-concept of the Modern Breakthrough was to function as an element in a literary and political public arena. Having functioned as arbiters of aesthetic taste, the critics now took on the mantle of ‘interlocutors’ in relation to the readership. Their key function was to be a mouthpiece for a public that – in reality or ideally – constituted the ‘general opinion’. The critics now had an important norm-shaping function in the public forum.

It is, however, clear that the female critics also, and to a large extent, saw themselves as intermediaries. Their role was to mediate the message of literature to the public, or in the terminology of the times: to the ‘enlightened’ and ‘cultivated’ public.

Female Public Arena

During the 1880s, women’s reference to personal experience and to the experience of other women begins to take on new import. The literary debate conducted by women increasingly takes the form of a separate woman’s discourse.

The message inherent in the new writing, about women’s lack of liberty, would seem to give the female reviewers a special legitimacy. Being female renders them capable of testifying to the veracity of a work from personal experience. Furthermore, they can appeal to other women’s experience of marriage, love, and suffering. The women have a common ‘empirical horizon’ from which the work of literature can be judged.

The women use the male writers’ works as the basis for an exchange of experience and for discussion. A particular female public arena takes shape, in which the focus is on women’s experiences, discussion emanates from a particular women’s horizon, and a specific literary norm linked to a ‘woman’s point of view’ gradually takes shape. The female public arena is, what is more, closely associated with the male-dominated literary and political public arena, in which liberal viewpoints now had tremendous impact. In many ways it nonetheless operates as a separate literary and social sphere. This is also whence initiatives for the organised women’s movement emanate.

Gina Krog exerted pressure on the leading liberal men in order to establish Norsk Kvinnesaksforening. This happened in 1884, and in the following year the society came under female leadership. Gina Krog also established Kvinnestemmerettsforeningen (Association for Women’s Suffrage) in protest against the ‘feminists’ who would not put the right to vote on their agenda. In 1887 the women’s journal Nylænde started publication.

Identification with the male propaganda writing did, however, continue to be an important aspect of the women’s self-perception. The Modern Breakthrough was seen as a kind of forerunner to the women’s movement. This reading of events has also characterised historical accounts of the Norwegian women’s movement: for example, Anna Caspar Agerholt’s Den norske kvinnebevegelsens historie (1934; History of the Norwegian Women’s Movement).

The awareness of writing and ‘discoursing’ from a common perspective of women’s experience emerges in, among other things, the frequent use of the ‘we’ form in literary reviews. This signals that the writer is not only writing on her own account. And it is clear that this is a female ‘we’. Amalie Skram used the ‘we’ in a review of Kielland’s novel Gift (1882; Poison), for Nyt Tidsskrift in 1883, and when Hanna Butenschøn wrote about Bjørnson’s play En Hanske in 1886 she stressed that the play had awakened women in general: “I know that many women had the same reaction as I did when Bjørnson’s En Hanske first appeared. It was as if we awoke from a dream and had instantly taken a long, heavy stride into real life […] The book itself was simply like an assembled, liberating expression of what we all thought and felt […].”

The ‘Gauntlet’ Point of View

The emergence of a dividing line between the sexes in the literary and political public arena is not unique to developments in Norway.

A significant historical factor behind the split between men and women in the literary and political public arena was that the male section of the bourgeoisie and rural population had now achieved the right to vote and greater political democracy by virtue of parliamentarianism, whereas women still had long to wait before gaining voting rights, and it was but slowly that their demands for financial and legal equality were fulfilled.

Seemingly peculiar to Norway, however, is that this dividing line was not more firmly drawn from the outset. On the contrary, the women became aware that their views on literature, morality, and politics had impact among the radical men. They felt, and made others feel, that it was women who set the terms for the debate – moral and literary alike. To them, the 1880s was the decade of the woman. Moving into the 1890s, Arne Garborg spoke of a ‘feminised’ era. The German-Danish antifeminist Laura Marholm (1854-1928) referred to the period in similar terms when she published Das Buch der Frauen (The Book of Women) in Christiania in 1894.

The key to the women’s experience is to be found in events surrounding Bjørnson’s play En Hanske. The drama centres on a young woman, Svava, who is engaged to be married, but she discovers that her fiancé has been keeping an earlier sexual liaison secret from her. She breaks off their engagement – by throwing a glove in his face. In the first version of the script, the breakdown occurs in the second act, and the remainder of the dramatic arc comprises Svava’s realisation that it is common for men to have sexual relationships before they get married, and also to have extra-marital affairs. This also applies to her own admired father. Svava’s mother tells Svava about the cover-up of the fiancé’s previous experience of women; Svava, however, sticks to her claim that the man she will marry must meet the demand made of her: he must be ‘pure’.

The play was the most epoch-making or – if you like – most disastrous text of the Modern Breakthrough. Its publication set off a heated dispute, which continued to rage for pretty much the rest of the decade under the name the ‘gauntlet dispute’, part of the ‘morality feud’. The dispute later came to be known as “The Great Nordic War over Sexual Morality”. The disastrous aspect of this ‘war’ was that it made for division between the most prominent radical intellectuals. Moreover, it made for a deep divide along gender lines; a gulf that the history of literature has passed on to each new generation via a picture of the period that fails to appreciate the significant role played by women.

Hanna Butenschøn was not the only one to join in women’s enthusiasm for En Hanske. Amalie Skram, too, applauded the message in the play – albeit to a lesser extent its dramatic form – when she assessed it in Dagbladet in November 1883: “From various parties one has heard that developments were moving in the direction of the woman being given the same freedom as the man to possess and discharge the prerogatives of the single life, without this in theory or in practice being injurious to her. It is, however, not difficult to envisage that a measure of this sort would lead to circumstances which in all respects would be just as reprehensible as those now obtaining, and would before long cause a reaction that would most likely endeavour to establish a downright Old Testament state of affairs.”

Women’s Triumph

These words not only express a common female experience, they also voice a degree of triumph. For the fact of the matter was: Bjørnson had now had second thoughts. He had fallen in line with Amalie Skram and other women as regards the way in which sexual morality could be changed. When he joined the radicals in 1877, he had also immediately taken on board the most radical stance on sexual politics – putting ‘free love’ on the agenda. Like the Brandes brothers and many others, he considered sexual liberation to be an absolute prerequisite for social liberation.

One of the people he attempted to convince was Amalie Skram. This is apparent from all the letters they exchanged in the early days of their acquaintanceship, when sexuality and eroticism was a very regular theme. Bjørnson insisted that Amalie Skram had no understanding of the liberating potential of sexuality; he was of the opinion that it held an opportunity to realise social as well as personal wellbeing: “And it will be women who espouse free love (the form will be as eventually clarified by the discussion): for women’s emancipation lies in this, only this. Her well-being lies here too.”

In this matter, however, Amalie Skram showed a remarkable reluctance to learn. Personal experience had made her sceptical, but she also had weighty social arguments.

There was no applause for the ‘gauntlet’ from the radical male writers. Most of them reacted with disappointment and anger. Writing to the Brandes brothers, Alexander Kielland cracked jokes about what he considered to be the play’s ridiculous message:

“I had to laugh heartily at A Gauntlet; he has met some chaste firebrand ladies in Paris – including my sister [the painter Kitty Kielland], and through big and fine words he has then – in the middle of Paris! had this idea about the cold veal – about young men, who by means of an icy compress preserve this precious treasure, so as not to see or know anything of the greatest pleasure in the world, before a clergyman has lain them next to an equally ‘pure’ piece of cold veal, for the reproduction of the family.”

The tone is here in keeping with that which had previously obtained between Kielland and Bjørnson in their exchange of literary and personal experience. Now Kielland clearly feels alienated; but, mind you, he takes care not to air his disagreement in public. August Strindberg, on the other hand, did not hold back; he felt betrayed and abandoned by a man he had hitherto almost loved. And he blamed the women: “Beware, BB, the stealthy, deceitful women’s movement; it is the upper-class’s fiendish tactic against us […] You have admitted to me that you wrote En Hanske in order to get the women on your side, as all others forsook you.”

“Akta dig, BB, för den krypande, falska qvinnorörelsen; det år övferklassens djefvulska taktik mot oss […] Du erkånde för mig at du skrifvit En hanske för att få qvinnorna med dig, då alla andra övergåfvo dig.”

Perhaps Strindberg was right in terms of Bjørnson’s political intentions with the play. Bjørnson was indeed an impassioned man with a distinct feel for the erotic, and he also had a great need of intellectual kinship with other men, but at that time he was also a determined politician, and he had encountered reluctant reactions from Amalie Skram and other women in respect of the free love manifesto.

Perhaps Bjørnson also saw his new stance as being an effective signal to the Norwegian bohemians. They were a small group of chiefly male artists and critics with some anarchist inclination who rallied around the writer Hans Jæger and the painter Christian Krohg. They published a little journal, Impressionisten (The Impressionist), which of course appeared at irregular intervals, and they could be called a rival group in relation to the ‘cultured’ circle around Nyt Tidsskrift. In 1882 Hans Jæger gave a lecture in Kristiania Arbeidersamfund (Christiania Workers Society), defending free love and arguing for the legalisation of prostitution. The lecture caused a terrific stir, women in particular taking exception. With En Hanske Bjørnson signalled the same difference of opinion.

Orgasm and Sexually Transmitted Disease

It was not actually in Paris at all, but in Boston, that Bjørnson’s belief in free love had been most vigorously undermined. In all the many discussions he found himself having with male colleagues and former allies, he makes particular reference to what he considers to be new scientific results from studies of female sexuality made by female American doctors, who he had personally met while in the US. Their view of female sexuality deviated from the prevailing radical paradigm in two significant respects: they ascribed the woman greater capacity to achieve orgasm while, at the same time, they claimed to have proof that sexual abstinence was not harmful, neither physically nor psychologically.

The American women’s movement of the Victorian age had turned women’s celibacy or passionlessness into a feminist virtue, and from this standpoint it was suspiciously providential that some of them could also ‘prove’ that sexual abstinence was not harmful. More problematic, presumably, was the discovery of the woman’s capacity to have a series of successive orgasms. On the face of it, this would seem to contradict the first ‘scientific’ results, but Bjørnson nonetheless managed to make it all fit. He wrote instructively on the matter to Strindberg: “(In) Mill and Spencer, Schopenhauer, Huxley I have read about it and a number of related opinions of great disparity for and against; in America, a female professor of medicine (anatomy) explained to me the physical facts of the woman’s sexual drive, to my astonishment I learnt that it is several (6) times stronger than the man’s; it can be calculated from the strength of that part which gives stimulation.”

His central point was that the woman did not for that reason become promiscuous. In his eyes the woman still possessed a moral superiority. Her qualitative merit was manifested by the fact that she “can nevertheless […] control herself!” if, that is, “she is not seduced and enticed by far too fiendish arts”. There is also hope for the men, however. “I have heard about all the measures discipline now has at its disposal in order to subdue and control,” he writes, almost as if trying to console Strindberg.

Bjørnson had now stepped onto the path leading towards his grand theory of social development: that monogamy was the highest stage for humankind, with the woman as an important moral motive force. The theory evolved in a kind of polemic interplay with the other male Modern Breakthrough writers, who refused to accept his as well as the women’s outlook on sexual politics. In the following years, they rained down charges of prudishness, puritanism, and sexual angst on Bjørnson and feminist women alike. While Bjørnson came increasingly to play a solo role in the public arena, the women’s public arena developed its own argumentation. This was often just as ‘scientific’ and just as moralistic as Bjørnson’s, but it retained its connection to the actual female experience and to an actual social commitment. The tone, however, more frequently changed into one of desperation.

This desperation was particularly apparent in the discussion about prostitution and sexually transmitted diseases. The agenda of the Modern Breakthrough was directed at the sexual angst underlying the old, Christian notions of sin, but there is much to suggest that the modern viewpoint itself activated these frightening notions. Moreover, the ‘modern’ individual had an actual fear on which to hang the nightmare: syphilis. During the nineteenth century syphilis had spread throughout Europe on a scale seen as catastrophic.

Naturalism Rejected

With the ‘gauntlet’ dispute, what started out as a conflict of interests vis-à-vis sexual politics took on more direct aesthetic implications, which led to the women’s public arena and also the Bjørnson-Sars wing denouncing naturalism as a literary school of thought.

During the early days, the Modern Breakthrough milieu had been an open one. The agenda was ‘propaganda’ and true depiction of society, without subjugation to specific aesthetic norms. Émile Zola was often mentioned as one of the ‘moderns’, but naturalism as such was not considered any absolute model to follow. In a Norwegian context, Amalie Skram was one of the first to make a clear distinction between the respective aesthetics of realism and naturalism. In her review of Kielland’s Garman & Worse (Dagbladet, 1 June 1880), she noted that Kielland was not a naturalist, but a realist:

”Alexander Kielland is a realist, and as such he is only concerned with those facts of life seen in the light, as opposed to the naturalists’ subterranean anatomy, which scrutinises the character and range of the state of being and with the skill of a veritable sleuth-hound pursues the process of evolution […].”

In 1883 Nyt Tidsskrift printed a lengthy article by Gerhard Gran presenting Zola, which could indicate that the editors ‘approved’ the naturalism agenda. When Mathilde Schjøtt reviewed Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler’s works Ur lifvet (1882; From Life) and Sanna kvinnor (1883; True Women) in 1883, she thus made a point of the fact that they might indeed be depressing, but that their modernity, and also their worth, lay precisely in this aspect: “depressing they are, and that they must be, because they are so modern,” she wrote. Pessimism was often identified with naturalism. Gradually, however, the female critics were quicker to disavow naturalism, both in newspaper and journal reviews. Mathilde Schjøtt, as well as other female critics, make increasingly frequent use of condemnatory wording as regards the “morbidity”, negativity, and pessimism connected with naturalism – the reason being that this implies a deterministic and pessimistic outlook on society, which is contrary to the forward-looking perspective of the Modern Breakthrough, and which moreover has anti-development and anti-women tendencies. The terms ‘bohemian literature’ and naturalism also become more and more synonymous.

Paradoxically, this development had specific repercussions for Amalie Skram. It did not help that she was a confirmed advocate of the ‘gauntlet’ point of view. Bjørnson – taking the lead for her entire old Christiania circle – saw to it that Constance Ring (1885) was written off. This resulted in a seven-year break in their friendship. When later explaining the background to his dismissal of the novel, Bjørnson referred to her distinctly naturalistic debut short story, “Madam Høiers Leiefolk” (1882; Madame Høier’s Lodgers), as a contributing factor.

However, the naturalist-oriented critics and authors also took a negative attitude to Amalie Skram’s first work. Rumour, to which Amalie Skram herself refers, said that it was the ‘gauntlet opponent’ Kielland who had counselled the Gyldendal publishing house to reject the novel. In the Norwegian context, Arne Garborg was an exception: he wrote a robust defence of Constance Ring in Nyt Tidsskrift. The female public arena, on the other hand, kept silent about the novel and, indeed, about the rest of Amalie Skram’s literary output in the 1880s.

The female public arena also, of course, spurned Hans Jæger’s novel Fra Kristiania–Bohemen (1885; From the Christiania Bohemia). The novel was banned and immediately impounded upon publication. The ‘moderates’ and the women protested against the confiscation, but they took a negative view of the work itself – both in terms of aesthetics and content. Considering Gina Krog’s assessment of the novel, the women’s reaction was surprisingly low-key: “The gospel preached in the book, and which the author proposes as the remedy for most misfortune in society, is free and – what is more – preferably short-lived love affairs between man and woman,” she wrote in a ‘correspondence’ to Framåt (Forward) in Gothenburg in 1886. She described the novel as being Romantic:

“in arch-Romantic fashion, the philistine community is flogged because it does not make allowance for ‘the deep craving’ felt by the men of the future ‘with the great need’ – but compare how Zola, the slightly more consistent determinist, treats the whining despisers of society.”

The author himself, however, makes a surprisingly good impression, as Gina Krog reports from a public debate:

“For all those who merely know him through the naive preface and the audacious book – from an artistic view not utterly worthless, but indicating little capacity for thought – it was astonishing to realise that here we actually had an intelligent man.”

The Albertine Affair

The superior tone colouring many of the women’s literary articles in the mid-1880s is a clear indication of their strong position within liberal opinion-making. This also applies to the reception given to another ‘bohemian novel’, Christian Krohg’s Albertine, published in the autumn of 1886. The story tells of a young working-class woman who, with a mixture of horror and desire, is drawn towards life in the city where her sister had earlier worked as a prostitute. She eventually falls victim to cynical abuse committed by well-to-do men and an official in the police service, and she ends up in prostitution.

From a literary point of view, the novel is a far more significant work than Hans Jæger’s, but the narrative is even more controlled by a naturalistic logic of destruction. The female public arena nonetheless approved unequivocally of the novel, but they did so by redefining it, so to speak, as a ‘novel of protest and indignation’ in tune with their own aesthetic and feminist perspective of expectation. Margrete Vullum created quite a stir by publicly defending the novel in her full name. She called it a “lovely book” and saw it as an unambiguous contribution to the campaign against the legislation on prostitution, a campaign primarily conducted by women. The female public arena received support from the newly-established labour movement, and the demonstrations in connection with Albertine resulted in an end to the ‘regulatory system’ that had in effect functioned as state legitimisation of prostitution.

This literary and political victory presumably contributed to the triumphant tone of the first issue of the women’s journal Nylænde, launched in 1887. The first page carried a prologue written by Jonas Lie, and in a review of his most recent novel, Kommandørens Døttre (1886; The Commodore’s Daughters), Ragna Nielsen presented the triumph of propaganda literature and of feminism as almost a fait accompli.

The Laughter of Medusa

The women’s reception of Albertine can be seen as a strategic misreading. The heated dispute that took place in the 1880s’ literary scene threw up many ideological interpretations. Newspaper criticism nearly always involves a black-and-white rendering of fictional works. It was clear that the women’s public arena preferred to address texts they saw as sympathetic or in harmony with their own experience rather than texts that could be thought to attack women. Christian Krohg’s novel also marked itself out by means of a strong empathy with women’s lot in the depiction of Albertine. The female critics made no secret of their discontent with the novels by other ‘bohemian authors’ – such as Jæger and Garborg – who, if anything, made women the culprits. But they undertook remarkably little analysis of the texts.

Perhaps it is not so strange that Fra Kristiania–Bohemen escaped close scrutiny. Gina Krog excused herself to her readers by saying that it was simply forbidden to read the book and thus also for her to discuss it. One could, however, wish that its paradoxical message had been examined in its day. As in the works of Strindberg, the text treats of a threatened masculinity. The male central character, Eek, is intensely concerned about and an advocate of free expression of sexuality, but this sexuality takes the form of a compulsive and exhausting fantasy world that drives young men to their annihilation and death. The sexual encounter paralyses and destroys them. Encounters with women and women’s sexuality reach their climax in a biblical parable and a mythical image. This occurs when Eek explains why he himself must remain outside the new, free society that he desires and perhaps also attempts to create. To create freedom is to be confronted with the authority – God – but: “‘the Jews have an old saying: “whoever sees Jehovah, dies”. I have drained the cup of Romanticism to the dregs, and at the bottom I saw the face of Jehovah – it looked like Medusa.’”

In Greek mythology Medusa is a female monster with serpents for hair. Everyone who looks at her is turned to stone. Psychoanalysis has seen male angst of the castrating woman in this myth, and in Jæger’s text there is a clear parallel to the experience of petrification in the encounter with women. In the novel, Medusa represents the tragic fate that makes it impossible for Eek’s utopia to be realised. Moreover, the image transmits a forceful notion of a castrating female power emerging where God or patriarchal power is removed.

The novel substantiates the impression that women’s powerful presence in society and the literary establishment triggered a crisis in male consciousness. The Modern Breakthrough started out as the young men’s assault on a traditional society’s stagnated patriarchal institutions, but women’s active participation in both the literary and the societal revolt – participation to which the men themselves had been so conducive – provoked insecurity and anxiety around the men’s self-image, their authority and powers. Revolt against the patriarchal authority, along with the women’s insistent presence, became problematic and threatening to many men’s life experience. In a number of contexts, the Norwegian bohemians gave the impression of being an impotent minority, and they linked the impotence to female dominance.

Arne Garborg shared this view. In the novels Mannfolk (1886; Men) and Trætte Mænd (1891; Weary Men), he painted a gloomy picture of modern, rootless men in the nation’s capital. They live in constant depression, with shortage of money and without values. They have shabby relationships with working-class women, but harbour ambitions of marrying upwards. The novels make it more than clear that women were not alone in having contradictory notions of sexual instinct and desire.

But Garborg was an ironist who was always ambivalent in his attitudes. Characteristically, he began to worry about the gender chasm that had opened up. In 1891 he warned his male writer colleagues: “the manly ideal has fallen heavily out of fashion in those parts of the world where the women’s movement is at its most powerful.” He would, however, caution against tendencies to misogyny, because that exposed angst and “angst is not manly!”

Lack of manliness was not, however, the most conspicuous factor as the 1880s became the 1890s.

Happiness

In 1887, Margrete Vullum followed up her defence of Albertine with a pamphlet to which she gave the title Lykke (Happiness). In this she argued both for and against the ‘gauntlet’ perspective, suggesting that it had perhaps sustained double standards, and she made the bold proposal of allowing young people to live in free relationships in order to promote happy marriages.

Meanwhile, among the women writers who published their first works in the 1880s, , belief in happiness is strangely absent. Their works display neither the optimistic expectations evident around 1880 nor the exultant self-assurance manifested by the female public arena. The woman’s life as depicted in Amalie Skram’s naturalistic novels has no escape route. Alvilde Prydz, seen as the other major woman writer of the period, displayed the same pattern. She made her publishing debut in 1880 with the slim Romantic tale Agn og Agnar (Agn and Agnar). She had written it ten years earlier, and it is a thoroughly Romantic text. She did not make her name until 1885 with the short story collection I Moll (In the Minor Key), published by Gyldendal in Copenhagen. The general theme both in this and her next collection, Undervejs (1889; En Route), is that of women’s disappointed expectations. In the story “Smaastel” she uses unwavering irony to paint the portrait of a basically happy and trusting woman who is slowly stripped of all belief in her own worth in a stifling and narrow-minded society.

The Danish feminist Elisabeth Grundtvig took a very positive attitude to I Moll when reviewing it for the journal Kvinden og Samfundet (Woman and Society). She read it as a protest against the Romantic “idolisation of love”. Male reviewers were more sceptical; in their opinion the collection was too Romantic. The most striking feature of the stories is, however, the deep disillusion they express. In “Forventninger” (Expectations) we meet young Helene Ørn who throws in the towel when, after two engagements to be married, she at long last has to concede that women and men have different expectations. In “Valsen” (The Waltz) the story focuses on a young woman who dies of disappointment after she has broken off a love affair. Love never comes up to expectations. What is more, the sexes do not even speak the same language. Acknowledgement of this essential lack of understanding appears to involve the woman losing her very foundation. The time for expectations has passed. The young woman exclaims in despair to the narrator of the story, an older woman: “I have been […] turned out of my Heaven or my Garden! Whatever you would call it.”

The agenda of the Modern Breakthrough encouraged women to pick up their pens, but there were surprisingly few new women writers of fiction in 1880s’ Norway. Dikken Zwilgmeyer (1853-1913), who hid her identity behind the signature “K.E.”, published two short stories in Nyt Tidsskrift: “En hverdags-historie” (1884; An Everyday Story) and “Det er forskel” (1885; There is a Difference). As in works by Alvilde Prydz, the fundamental tone is one of disillusionment, but the style is more concise and more consistently ironic, and the social realism in description of toil and poverty gives the stories a stronger impression of protest.

Dikken Zwilgmeyer opens “En hverdagshistorie” (1884) thus:

“It would soon be twenty-two years since little madam Bruvold had achieved what is called her good fortune and married the leader of the church choir, Bruvold. She did not marry for love. Just to be provided for […] He got married because he was tired of housekeepers who would quit at moving time.”

A concise, somewhat wondering, style describes the little woman’s series of childbirths and endless daily work up until her death and burial. The eulogies at her funeral are addressed to her self-sacrificing husband:

“And before morning a soft carpet of snow lay upon little madam Bruvold’s grave. The wind swept across, sighing and whistling, each gust of wind sounded like a wail.

But little madam Bruvold lay snugly sheltered from all the harsh winds in the world.”

A Groundswell of Women’s Writing

Considering the quality of Dikken Zwilgmeyer’s debut works, it is strange that she did not publish more writing for adults. Her short stories attracted but little attention, as was the case with her collections Som kvinder er (1895; The Way Women Are) and Ungt sind (1896; Young Mind). She later published four novels for adults, two of which were the utopian Emerenze (1906), and Maren Ragna: et stykke livshistorie (1907; Maren Ragna: A Life). She was, however, far better known for her exceptional series of girls’ books, the “Inger Johanne” books, which were published in large print runs for many years.

Despite the impact of the women’s public arena, works by women writers had a tough time in the 1880s. It was almost impossible, for example, for Alvilde Prydz to find a publisher. She identified with the Modern Breakthrough, but fought a bitter and fruitless battle to win recognition from the leading male critics.

The situation changed in the 1890s. From around 1890 there was an almost explosive growth in the number of publications by women authors, many publishing for the first time, and the groundswell of literature written by women retained momentum across the turn of the century – a literary women’s decade thus paved the way for the major neo-realistic female oeuvres in the first few decades of the twentieth century: for example, the works of Nini Roll Anker and Sigrid Undset.

One factor in this development was that the Aschehoug publishing house, which now aimed to become established on the Norwegian book market in competition with Danish Gyldendal, had a positive interest in publishing women writers.

Mathilde Schjøtt had already seen what was coming when she reviewed Anna Munch’s (1856-1932) novel Kvinder (Women) in 1889. She quoted J. S. Welhaven, who had given notice that “a time is approaching when literature passes into women’s hands”, and she thought that now this had come to pass. Major women authors such as Camilla Collett, George Eliot, and George Sand were being followed by new, as of yet inexperienced, pens: “Courage and the sense of responsibility have arrived, and with courage the abilities will grow.”

During the 1890s Alvilde Prydz published seven novels, and then six more after the turn of the century. Anna Munch followed Kvinder with seven novels and a number of plays over the next twenty years. Helene Dickmar published four novels, three plays, and a book of memoirs after her debut publication. Drude Krog Janson published her first novel, En ung Pige,in 1887; she later published four novels, two under the pseudonym “Judith Keller”. All of these writers were influenced by the social and aesthetic agenda of the Modern Breakthrough, with its focus on realistic depictions and social critique. All of them also, in one way or the other, addressed the debate on morality and sexuality: by means of discussing the topic in the actual text, and also by shaping the storyline and its thematic patterns around conflicts pertaining to gender and femininity.

Most of the writers let it be clearly understood that they were sympathetic to feminism and the feminist perspective. This does not apply, however, to Hulda Garborg (1862-1934), who published her first work in 1892, the novel Et frit forhold (An Open Relationship). In 1904 she published Kvinden skabt af manden (Woman Made of Man), a mixture of essay and novel discussing Otto Weininger’s gender theory and formulating a critical outlook on liberal feminism and the new notions of femininity emerging in the 1890s. Minda Ramm (later Kinck) (1859-1924), in her first published novel, Lommen (1890; The Diver), also expresses deep scepticism of the ‘modern’ feminist. Her next novel Overtro (1900; Superstition), meanwhile, more readily follows the customary pattern for novel-writing of the period.

Protest and Hope