“‘Excuse me. What did you say, Maja Ekelöf?’

‘One understands […] that in the historical process, how the average person reacts is of great importance.’

‘Yes – you wrote that. Thank you, Maja’”.

These are the words of Rigmor, the main character in Ragnhild Agger’s novel Den halve sol (1989; Half the Sun), who calls in anguish upon the Swedish writer Maja Ekelöf and her Rapport från en skurhink (1970; Report from a Bucket). She dreams about a little place where she can have her books and her writing in peace. She dreams that her husband, Ove, and their grown-up daughters, Dinah and Gunver, will respect her wishes and support her passion. All her life, she has postponed this inner need for the sake of her family. She has been a wife, mother, housekeeper, done her duty, met everyone’s needs. Now she is waiting for the thanks – for the freedom, for the support to finally do just a little something for herself. It never comes. On the contrary. For Ove, books and writing remain a threat to their marriage. He wants to live, not read about living, as he puts it. And when Ove lives, Rigmor puts on a party! Rigmor is, despite her mature age, a good girl. She has always done what was expected of her.

Ragnhild Agger forms her novel as a process of recollection which results in a bitter self-awareness. It is a novel in which images of the conditions for men and women artists conquer Rigmor’s consciousness and throw her conflict between duty and inclination in sharp relief. Out comes the crime novel writer who – when she sits down to write – sticks her head out the door and yells: I demand some god damned peace and quiet! This is impossible for a Rigmor who does not have the audacity to believe in her artistic calling and assert her rights. Instead, she has encased herself in more and more masochistic forms with higher and higher demands of the others to prepare the way for her. Now she realises that only she can assert her right to read and write. She must be her own driver of change.

“When the lobster claw finally loosened its grip, she would write every morning before she grew tired.

She would begin immediately after breakfast. This is my work time, she would say, and I must not be disturbed! Once she got her book out, everyone would have to respect her time.”

Den halve sol, with its female artistic conflict and its focus on female self-sacrifice as partially self-induced, is a product of the late 1980s. Its view of the traditional women’s roles stems from the discussion about the unequal conditions for men and women which the women’s movement started in the beginning of the 1970s. The anger is intact, although the cause and the explanations cannot only be attributed to a general concept of oppression that exonerates women, placing all the blame on men and their social systems. A lot has happened since the early 1970s when Ragnhild Agger had her debut with the trilogy Pigen (1971; The Girl), Pladser (1973; Places), and Parret (1978; The Couple). A series of novels with an underlying women’s liberation point-of-view. They depict the conditions of life for women that send girls with literary dreams and young women from various places in the city and the country, who should have obtained an education, directly into marriage simply because she accidently got pregnant. She is called “she” – and is not an individual person but a gender. In Dagdigte (1979; Day Poems), in the collection of short stories På grænsen (1982; On the Edge), and in the novels Tågelandet (1985; Fog Country) and Den halve sol, she follows the pattern of inner and outer conflicts that affect these so-called traditional family women. The line in Ragnhild Agger’s work becomes partially representative of the succession of slightly older women who in the early 1970s – inspired by the new women’s movement and by the student revolt which linked criticism of the university with criticism of working conditions in the welfare society – use the pen to call attention to the conditions and conflicts of their own generations. They are not young, well-educated, or particularly rebellious […] They were young in the 30s and 40s, were very experienced as housekeepers, cooks, maids, cleaning ladies, factory workers, before they married and slowly but surely realised that involvement in the home, children, husband, and family was not enough for them. The prosperity of the 1960s brought them out into the labour market again, out to a new conflict between work in the workplace and work in the home. In contrast to the young generations of the new women’s movement, who were able in the beginning to quickly and programmatically reject the traditional women’s roles as passé, these writers claim that the change is both bigger and more difficult than one would initially believe.

Ditte Cederstrand (1915-1984) is the revolutionary with class disparities guiding her depiction of women’s conditions of life. She had her debut in the 1950s with the trilogy Den hellige alliance (1953-55; The Holy Alliance). It was the days of the Cold War and Ditte Cederstrand had trouble getting her books published. In the early 60s she travelled back in history in Livet det rige (1960; Life the Rich) and Over sukkenes bro (1962; Crossing the Bridge of Sighs), about a noblewoman’s meeting with the French Revolution and its ideals. In the 1970s, Ditte Cederstrand’s social realism finally found its place and response. In 1974 she started on the novel series Af de uspurgtes historie (From the History of the Unasked) in which Ditte Cederstrand follows a working-class family from the turn of the twentieth century: a literary revision of the history of the labour movement, focusing on family and women.

For some of these writers – Marit Paulsen, Grete Stenbæk Jensen, Benthe Østrup Madsen and, of course, Ragnhild Agger – the Swedish cleaning lady in Maja Ekelöf’s diary novel from 1970 is a common source of inspiration. Rapport fra en gulvspand became a seminal work both through its unpretentious diary form and through the rhythm that takes “the personal is political” literally and allows Maja Ekelöf to depict the depression-like mood swings that belong to the daily life of a low-wage working woman.

She becomes a heroine of daily life, although she is a far cry from a classic heroine. She had given birth to and raised five children, made a living as a cleaning lady her entire life, and is now, at the age of fifty, both tired and physically worn out. Her back acts up, her body aches, but her spirit is still willing, and it helps her create the view of the world from the bottom of a bucket that struck a powerful chord throughout Scandinavia. From this point of view, Sweden is not a welfare society. Even though poor relief has been replaced by the right to social services in difficult times, it is the human humiliations in the meeting with the system that are most notable. This was in 1970, and for most readers from the middle class, reading about this side of the welfare society came as a shock. And Maja Ekelöf’s special tone only added to the shock. She simply states things as they are, without complaining. On the contrary, she has the audacity to see herself as something special: poverty prevented material goods from becoming the fulcrum of her life. Instead, it has developed her eye for the kinds of life values and social commitment that cannot be bought. She is an uneducated, worn down, low-wage, single mother, but she has never given up hope of changing her situation. She finds her belief that she is somebody special at night school and in literature. Books become a life nerve, a lifeline, a personal university.

Literature gives her self-respect, reassurance, and knowledge. It involves her in a socially conscious dialogue across time and continents. In diary notes, she anchors this discussion in a dialogue with herself which both retains and recreates the cleaning lady. A lady with back pains, headaches, damaged and cracked hands, and all those children, evolves into a thinking, socially conscious person who has not lost faith in herself – the author. Rapport fra en gulvspand is the story of the author’s and first-person narrator’s own birth and personal emancipation – an ode to the soul and to literature.

Maja Ekelöf called her book “A cleaning lady’s diary” when she submitted it to a Swedish competition for best political novel. When it was published it was called Rapport (Report). This genre, typical of the 70s, elevates the private diary entries to the level of public documentary, and not only gives them the truth value of confessions, but also of the critical investigation.

1972 saw the publishing of the Norwegian-Swedish author Marit Paulsen’s Du, människa? (You, a Human Being?) with the subtitle “Sharp close-up view of the life of a female industrial worker”. According to the reviewer Torgny Møller in the Danish daily Information, “It should not be considered a literary and therefore harmless novel, even though the system and its henchmen are doing their best to put Marit Paulsen’s work into that box”. It was intended to be viewed as a report and read for its criticism of real life. Viewed with the eyes of posterity, this differentiation between fiction and reality, novel and report is difficult to maintain. Du, människa? is, in fact, a work of fiction. The literary take on reality is what gives it its impact. Maja Ekelöf described four years in the life of a cleaning lady and gave a personal voice to the many days in which there was no time for thoughts. Marit Paulsen describes, from hour to hour, a day in the life of a female shift worker. From four-thirty in the morning, when she staggers home in exhaustion to two-and-a-half hours of sleep before the children wake up and the family work starts, until she just finishes her next shift 24 hours later. A monotonous, fatiguing rhythm that is only broken by a small handful of holidays and days off. “You are woman, worker, employee, mother, low-wage earner, extra, production factor, spouse, consumer.

There is just one thing you have never been and may never be – human.”

The story is presented in a kind of continuous inner monologue, an ongoing argument between inclination and duty. In Paulsen’s work, the main theme from Maja Ekelöf’s Rapport fra en gulvspand is directly related to Aksel Sandemose’s “Jante Law” – “Don’t think you’re anything special” – only expanded to an image. Life as a theatre of the absurd with workers as slaves, mute extras who eat, drink, sleep, toil, and die:

“There is only one vital condition for the preservation of the system: that you and the other slaves have no self-confidence, you must not think you are anything special. Because the day you realise that you are everything – that the entire play relies on you – is the day you seize power.

That is why, little person, you must be crushed.”

In this life, the dream becomes a driving force, but also a nuisance. It requires a transformation of the energy deficit into an energy surplus – the energy to read and educate yourself, the energy to participate in union work, to support fellow workers, the energy to think and comprehend, to chase the vision instead of accepting the carrot.

The call for knowledge and education, the need to break free of the isolation of the family or workplace that was formulated in these books was embraced by the young student revolutionaries from 1968. Cultural fronts were drawn, discussion clubs and writing workshops were established. For a number of writers, these new relationships were of vital importance. They gave them the courage to write and the support to be published. Both Benthe Østrup Madsen and Grete Stenbæk Jensen started their writing careers here. Benthe Østrup Madsen started with poetry. Images of social commitment, dreams about a new community. A number of them were published in the anthology Fem-seks ting vi ved om socialisme (1976; Five or Six Things We Know About Socialism), which the socialist organisation Socialistisk Kulturfront published after a literature seminar. In 1977 she made the jump to the reportage genre with the novel Konflikt (Conflict), about the lives and working conditions of the “porcelain ladies” at the Royal Copenhagen porcelain factory. It, too, was in the form of a diary novel depicting the conflict between reality and dream.

“What was this dream of mine? Was it the dramatic and wonderful experience of solidarity during and after the strike that had me ‘dreaming’ that this could continue? … Well – the dream must be crushed as a dream. Now I know that the action starts with the individuals who each feel pressured in their daily lives – and together do something about it.”

The workplace, the relationship with the management, with the union, with fellow workers, have all become controlling factors. Konflikt depicts the narrator’s realisation, shaped, however, more as an introduction to the working conditions than as a personal story. It is more reportage than novel. At the same time as Benthe Østrup Madsen’s book came out, a number of professional workplace reports were released, which were immediately incorporated into the criticism of working conditions. The women’s literary efforts, on the other hand, moved in other directions.

From Maja Ekelöf to Marit Paulsen, a shift in tone and style occurred. A literary transformation brought together the criticism of women’s low-wage working conditions in a single image and held up the vision of an entirely different image, making the individual person’s attitudes and actions the focus. The tone is released by Marit Paulsen! It is bitter and angry.

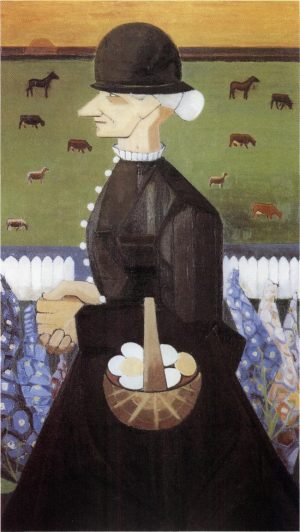

This is not the case with Grete Stenbæk Jensen’s debut novel Konen og æggene (The Woman and the Eggs) from 1973. It is inquiring, understanding, hesitant. Furthermore, it is based on real diary entries, although in the novel they are reformulated into an inner monologue. A story about the life of Martha, an egg packer, from dreams about marriage and becoming a lady in her childhood garden behind her father’s village workshop to dreams about solidarity among the women at the egg packing plant; solidarity that would be able to change and humanise their conditions. Dreams that are destroyed, all at once.

Marit Paulsen’s slavery image and Maja Ekelöf’s humiliation theme wind through Grete Stenbæk Jensen’s novel, launching new scenes in the reportage theatre between the welfare society and women working in low-wage jobs. The perspective is the same. Not until the conditions are brought to light can awareness of the injustices grow and enable change. However – a shift in perspective also takes place: Grete Stenbæk Jensen asks what it is that makes rebellion so impossible for our generations. In Ragnhild Agger’s work, the same question prompts a psychological examination. She wanders into a mute borderland and creates images of all that goes unspoken – bitterness, disappointment, experiences of betrayal, which like a shawl pass from mothers to daughters and sons. The rebellion that was turned inward grew into a tumour. With her complex style, in which dream and reality are interwoven in a psychological pattern, Ragnhild Agger represents the modernist of this landscape, as Grete Stenbæk Jensen is its realist.

Grete Stenbæk Jensen abandons the problems of the modern workplace and begins a cultural-historical exploration of the quiet rural women who slave away without any comprehension of the meaning of modern solidarity. They acquire their experience from the family farms, they become the foundation for a series of new cottage industries that pop up in the 50s and 60s, and they are sacrificed when smart new management techniques take over. Grete Stenbæk Jensen’s exploration of this special type of woman begins in Waterloo retur. 10 beretninger (1978; Waterloo and back. 10 Stories) and is expanded upon in the novel Martha! Martha! (1979), which makes the leap into the epic novel series about the development and decline of agriculture, centred around Thea, a self-conscious, confined country girl whom we follow from birth to death. A quiet but strong tale of a generation of women who stubbornly followed their own path. Grete Stenbæk Jensen has become the great interpreter of these quiet lives. And with Anes Bog (Ane’s Book) from 1992 and Kære Faster (Dear Aunt) from 1994, she adds with care new portraits and new dimensions to the history of this generation of women.

Beth Juncker

Authors Late in Life

In the 1970s, a number of older women had their debut as fiction writers in Sweden. Anni Blomqvist (1909-1990) was fifty-seven years old in 1966 when her first novel I stormens spår (In the Wake of the Storm) was published. The first volume of her series about Maja on Åland, Vägen till Stormskäret (The Road to the Storm Skerry) came out in 1968. With her first novel, Jungfru skär (1975; Maiden Fair), Helga Bergvall (1907-1978) became known as “The pensioner who became an author”. Herta Wirén (1899-1991) was seventy-five years old when she made her debut with En bit bröd med Anna (1975; A Bite to Eat with Anna). What had once been their handicap – that they were working class women – suddenly became interesting.

In modern times, women writers have also longed for a room of their own as Virginia Woolf did. Time, money, self-confidence, and education have been in short supply, preventing them from writing. Ingrid Andersson, like Mary Andersson, did not begin writing seriously until after a period of sickness. Before then, she would sit in her wardrobe (so as not to disturb anyone) and write “little things”. Herta Wirén hid her manuscripts in the tiled stove; Helga Bergvall hid hers under the worktable.

They were applauded as the heroines of the everyday and the forgotten histories, and the entire literary establishment backed them up. Their work resembled that of Linnea Fjällstedt (born 1926), Ingrid Andersson (1918-1994), and Mary Andersson (born 1929), who can be included in the same group, from a woman’s perspective telling the history of the marginalised – workers, poor farmers, and small fishermen. Herta Wirén and Mary Andersson wrote about the working-class neighbourhoods of Malmø. In the autobiographical novels En bit bröd med Anna,

Dofta vildblomma röd (1977; Fragrant Wild Rose Flowers), and Räck mig din hand syster (1979; Give Me Your Hand Sister), Herta Wirén, who at the time of her debut was the widow of an active union organiser, describes her upbringing in the labour movement. The novels are set around the turn of the last century and Elsa, who is her alter ego, is proud of her family. They are talented and hard-working, and are committed to the struggle for better conditions; they participate in Labour Day marches, are teetotallers, and active in their unions. Elsa herself is both free-spoken and intelligent, and the reader never doubts that everything will go well for her.

In Mary Andersson’s novels, the women are both weaker and more vulnerable. They cope with daily life and poverty with humour and perseverance, but it is often the men who make their lives difficult. The men are unreliable and brutal, and Mary Andersson depicts the many ways in which women handle love and sexuality. The stories alternate between gruesome attempted abortions and powerful cravings, sexual unwillingness, and the reading of sheik stories. Everyone dreams about escaping the squalor and finding a life of love and beauty, and the title of Mary Andersson’s first novel Sorgenfri (meaning “freed from sorrow” in Swedish), 1979, which is named after one of the poor working-class quarters in Malmø with the highest population of children, is not only extremely ironic but also addresses this dream.

The older women in Mary Andersson’s novels have retained many of the norms of their peasant society, but in the city they have lost their dignity, and their daughters are struggling not to repeat the lives of their mothers. The main theme in Helga Bergvall’s trilogy Jungfru skär, Jungfru vart tog du vägen? (1976; Maiden, Where Did You Go?), and Livslögnen (1978; The Life-Lie) is also the daughter’s attempts to avoid the fate of her mother. Her mother, who in her youth was abandoned by the man she loved, who became pregnant by another man who also abandoned her, and who was forced to give up two children before she could marry an alcoholic farmhand who is the father of the main character, Kerstin. He constantly doubts her paternity, is violent, drinks, and abuses Kerstin’s mother. Both mother and daughter escape from him, but Kerstin carries the terrible memories within her. In the city she flourishes, becomes a seamstress, and creates beautiful designs that excite men’s admiration. Naive and sexually ignorant, she becomes an easy victim of her own sexuality, and abortion becomes her last resort.

In Helga Bergvall’s stories, sexuality is something good that turns bad, because it unfolds on men’s terms. Just like in Linnea Fjällstedt’s Hungerpesten (1975; The Hunger Plague), the man becomes a threat to the woman’s survival, even though she has chosen him out of love. In Hungerpesten Matilda stays with her husband despite his drinking and repeated assaults. He is a plague, but she still cannot live without him. And when he dies – struck by lightning – she must give up her children to others because she is unable to provide for them.

With Hungerpesten Linnea Fjällstedt sought to rehabilitate her own grandmother by telling her story, and Fjällstedt’s other novels Ödeslotten (1977; Luck of the Draw) and Befrielsen (1979; Liberation) are based on the authentic accounts of people to whom she sought to give a voice. All these works are characterised by the same effort to rescue people and life circumstances from oblivion. This cultural historical ambition is also clearly evident in the work of Ingrid Andersson. In Två berättelser (1975; Two Tales) she tells the stories of people who lived in the region of South-East Norrland when her parents were young. In Barnet (1978; The Child) she depicts her own childhood. It is the history of an already vanishing culture, where the women are the socialising forces while the men appear as the most powerful and fascinating.

The culture of which the women are bearers is depicted in the work of Ingrid Andersson as well as the other writers as both an advantage and a disadvantage. In the five novels about Stormskär’s Maja from Åland, Anni Blomqvist describes in detail the cultural tradition of which Maja is a part. It is based on hard work and survival strategies. Maja’s work is demanding, but also creative, and at the loom she can dream about beauty. Maja loves her Janne, but she must always be subordinate to him. “The priest says that Maja was created for Janne’s sake, but not that Janne was created for her sake,” writes Anni Blomqvist, illustrating how religion is used to oppress women. But she also shows how the mutual dependency between man and woman creates a loving fellowship because they would not be able to survive without the other’s work.

Enel Melberg

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd