“– You devil, she screams at the angel, you false prophet and distorter of vision! You sit there and rave about my golden lustre, my perfection, you sit and daydream – the time will come when you shall be uprooted from them and see that I have left. Gone. Don’t exist. Didn’t want to be here […] I don’t want to be stuck, I don’t want to be categorised. Not even by myself. Isn’t it true that everything that is said and supposed always veers into a lie? Sooner or later?” I hennes frånvaro (1989; In Her Absence).

In Eva Adolfsson’s (born 1942) debut novel I hennes frånvaro, the angel of traditional womanhood is transformed into a conversation partner who awakens the protagonist Gertrud’s urge for opposition. Gertrud opens a gap in her chest and reveals her black interior. But the image of the woman who proudly shows off her monstrous inside is ambiguous. Gertrud was once a mermaid. She was permitted to rise up to the prince and the human world if she pawned her tongue with the witch at the bottom of the sea. Far down there in the shimmering depths of the ocean she could sing her own song: strong, beautiful, and genuine. The word ‘bird’ flew and the colour ‘red’ glowed. In our world, Gertrud finds it hard to express herself. She is torn between the desire to return to the depth of the sea – to an existence beyond the one we know – and to rise into the shining world above the surface, which renders her mute.

Through the mermaid motif, Eva Adolfsson tests women’s opportunities to express a singularly female identity and experience in a language that is completely their own. Exploration of the possibilities of language necessarily affects our ideas of how we create identity and pass on our experiences. In Swedish women’s prose of the 1980s, we find an attitude that is focused on the self and is explicitly critical of language, as well as a thematisation and revision of monstrous and angelic traits that relate to the tradition of women’s literature. There is even a strong will to re-establish, rather than question, the possibilities of language in terms of depicting and reforming the personal history of the self and the universal history of tradition.

Like Nina in Victoria Benedictsson’s short story “Ur mörkret” (1888; Eng. tr. “From the Darkness”), the protagonist Siri in Gunilla Linn Persson’s Skuggorna bakom oss (1989; The Shadows Behind Us) sees herself and the surrounding world through her father’s eyes and language: “When Siri thought it was father’s voice, the great, warm voice, that read her thoughts out loud inside her head. She thought in his voice, as some think in their mother tongue.” The girl’s language is not her own, nor is it her mother’s: it belongs to her father. Unlike Nina in Victoria Benedictsson’s story, Siri breaks loose. The ties to the father are brutally severed, and she starts to hear her own thoughts in her very own language: “She had thought. That was the strange thing. She had heard her own voice there, inside her head. Just a few times his voice, which always thought her thoughts, had penetrated and spoken within her.”

To Erase and Draw Identity

In their novels, Barbara Voors (born 1967) and Gunilla Linn Persson (born 1956) often seek out a mythical land of origin where the female self is centre-stage along with the young woman’s attempts to break out of a stifling environment. They take their point of departure in the Western story of mother, father, and children, and they show how hard it is to find an identity of one’s own outside the family. Both Gunilla Linn Persson and Barbara Voors concentrate on how the girls’ consciousnesses are affected by family and love-relationships. Social factors are vaguely suggested as something both threatening and alluring, but never gain clear, realistic outlines. The domain of the young girl remains the mythical and fairy-tale-like.

In Barbara Voors’s Tillit till dig (1993; Trust in You), a pronounced conflict between a female fantasy world and a male presumed reality plays out. The protagonist, Saga (Swedish for fairy-tale), is a writer who tells stories and lives a shielded life. She wants to find a new language that can express the self and its place in the world better than the existing one. When she meets Zacharias, she believes that she may finally take part in the real world she has so desperately been searching for. But the world of men is just as deceitful as her flight into the world of fairy-tale and fantasy. It turns out that the nature of story-telling implies a paradox: telling stories is not just a means of escape, it is also a path forward. Every chapter in Tillit till dig has a letter of the alphabet as a heading; the novel is composed as a path to insight that leads from A to Ö. When Saga tells stories, she represses her difficulties, but at the same time, the very guilt and the wound that she tried to escape through the story are bared. There is a healing power and potential in storytelling, after all.

Marie Hermanson (born 1956) uses the world of fairy-tales to tell a story about female identity in a rather more explicit manner than Barbara Voors. In Hermanson’s novel Snövit (1990; Snow White), she lets Snow White and her Stepmother incarnate two common stereotypes in the history of literature: the angel and the witch.

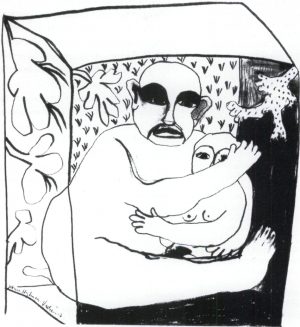

The Stepmother and Snow White personify two sides of a problematic femininity. The one represents aggression and female sexuality, which has traditionally been seen as dangerous and monstrous, the other is a genderless and angelic neuter that lacks any biological foundation for its identity. Snow White’s attributes – the band tying in her waist, the comb, and the apple – neither beautify her nor grant her wisdom; they deform and are meant to kill her. The prohibited bite of wisdom casts Snow White into a death-like sleep and places her in a coffin of glass – the ultimate image of the woman as fetish and fixed object of admiration: “There she lies, like a present in her box. […] A place without life, without death, without movement, without decomposition.” Salvation is finally found in the form of the Prince, who brings her back to the protective order of the castle.

Marie Hermanson rewrites the tale of Snow White and her Stepmother without transforming their established roles. Gunilla Linn Persson employs the opposite strategy in Människor i högt gräs (1991; People in Tall Grass). She attempts to leave the traditional narratives about female identity behind in order to, to the furthest possible extent, construct new ones based on her own experiences.

Gunilla Linn Persson’s novel is constructed around the filming of the TV-movie En släkting korsar sitt spår (1991; A Relative Crosses Her Tracks). In both the film and the book, she depicts her search for her adopted mother and her own origin. The novel therefore has strong autobiographical and documentary traits.

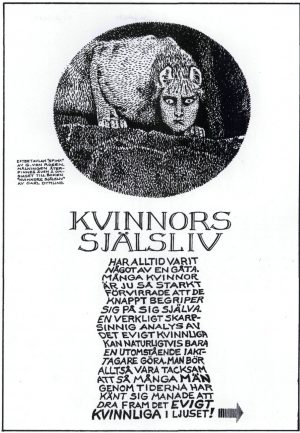

The invisible and guilt-ridden history of the women’s world haunts the protagonist Gunilla during her work on the film. The visible – the male – is by definition what is real, and it is valued higher than that which cannot be measured, weighed, or accounted for in financial terms. The women’s world is invisible, and is therefore not allowed to become history. There is no narrative of the return of the prodigal daughter, says Gunilla Linn Persson, because it was either shameful or never sufficiently important that a daughter disappeared. Gunilla Linn Persson unveils her own invisible women’s history, and points to the necessity of possessing knowledge of one’s ancestral mothers and their lives. The inherited facelessness can only be dispelled by narrative and the writing of history.

“You who come of a younger and happier generation may not have heard of her – you may not know what I mean by the Angel in the House. […] In those days – the last of Queen Victoria – every house had its Angel. […] The shadow of her wings fell on my page; I heard the rustling of her skirts in the room. […] I turned upon her and caught her by the throat. I did my best to kill her. […] Had I not killed her she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing. […] She died hard. Her fictitious nature was of great assistance to her. It is far harder to kill a phantom than a reality.”

(1947; Virginia Woolf: Professions for Women).

In Inger Edelfeldt’s (born 1956) collection of short stories I fiskens mage (1984; In the Belly of the Fish), the conflict between the apparently innocent girlhood-country and the adult world is accentuated. The girls whom Edelfeldt portrays have both a magical and a problematic relation to their own growing up and to the surrounding world.

Jenny in “Snälla snälla Jenny” (Sweet Sweet Jenny), from I fiskens mage, seeks deliverance through a destructive pattern. She goes into her mirror-sister’s holy, monastic room. The mirror-sister is pale and skinny, and she turns around and speaks her name: Anorexia. Through hunger, Jenny is transported to a nun-like holiness where the self – the soul – expands at the cost of the body. To eat is the same as displaying spiritual weakness; to master hunger means being in absolute control and becoming pure spirit: “She can stop herself, close her eyes and experience how her body is only a thin shell, how the hunger sharpens her mind until she feels fulfilled, becomes a vessel of glass, fully moulded with evening sky, trees, and sleeping earth.” Jenny is transformed into a genderless, natural neuter, into a Snow White in a glass coffin.

The protagonist of Kamalas bok (1986; The Book of Kamala) handles and structures an increasingly chaotic emotional life through food. We are never told her real name, but she works in a gift-shop called “Fine Little Things”. Her life and her ways of expressing herself are just as nauseatingly cute as the tasteless things she sells in the shop. By using a first-person narrator to tell Kamala’s story, Inger Edelfeldt succeeds in reproducing the linguistic paucity and mental naivety of this young woman. There is no intervening narrator who clarifies or elucidates. The reader is entirely given over to the girl’s own consciousness. But underneath her apparently unconscious superficiality all is chaos.

When her boyfriend goes on vacation without her, her forced, Barbie-like façade breaks down. She is invaded by Kamala, a woman in animal shape who is loathsome and wolf-like, everything the woman in the gift shop is not allowed to be. Kamala is her repressed self and distorted mirror image. Kamala eats for comfort, starves herself, and locks herself into her flat and lets it fall into disrepair. She takes over the woman’s self, and the novel ends in a painful conflict that recalls Snow White’s dilemma. Either the nauseatingly angelic is affirmed at the cost of aggressiveness, or the monstrous takes over.

Inger Edelfeldt portrays girls who have a tendency to use food as a weapon with which to torment themselves. In Carina Rydberg’s (born 1962) novels, the masochistic traits express themselves in direct connection with women’s sexual relations to men. The only thing Carina Rydberg’s women and men can be certain of in an increasingly meaningless world is degradation. This is where sado-masochism becomes relevant. What will the views of the individual’s role in society look like when the fight of good against evil has played out its ethical role? What then remains is to seek a clearly delineated and norm-transgressing experience that repudiates indifference. The path thither is violence and the authoritarian sexual relation, which assumes a holy dimension.

In Carina Rydberg’s novel Månaderna utan R (1989; The Months Without R) , the bisexual hero with sado-masochistic tendencies is rightly named Markus, for the saint. He is a handsome young man, a depraved twin of the boy in Thomas Mann’s Der Tod in Venedig (1912; Death in Venice). Camilla, the novel’s protagonist, also meets him in Venice, a city with an air of ruin and a shabby grandeur that borders on the histrionic and depraved. “– I always act. That is the only reality for me,” Markus says. He plays the parts he thinks are expected of him, and remains a blank surface without any depth.

People never are what they seem to be, Carina Rydberg appears to think, but their hidden sides contain no mysteries. They are types who transgress sexual conventions, lacking psychological substance. The reader is left uncertain – we are never told more than what is contained in the conversation or is reflected in the actions of the characters. In Osalig ande (1990; Unblessed Spirit), the transgressions take on extreme and humorous forms. The protagonist Marika kills herself but refuses to leave Earth for a life in Heaven. Like an unblessed spirit, or like the alter ego of the writer, she observes her near, but not always so dear, friends and relatives.

Carina Rydberg does not write Bildungsromans or novels of development. Her women are not heroines who strive for self-realisation: they are, rather, intermediary objects between men. All men in Osalig ande are bi- or homosexual, and women are used as a subterfuge to reach another man. When the man looks at a woman, he really desires the man she is supposed to desire. It is therefore logical that the unblessed spirit Marika is eventually reborn as a boy; as a girl she was far more limited, both sexually and socially.

In Mun mot mun (1988; Mouth to Mouth) and Lilla livet (1993; The Small Life), Nina Lekander (born 1957) has in a cutting and humorous manner captured the young woman’s conflict between career, coupledom, and motherhood. The woman of today has great freedom to ‘realise herself’, but an ideological emptiness plunges reality into a vacuum. Despite being conscious of the traditional traps for women, the women Lekander depicts lack faith in solutions that transgress the private – they see through the system, but no change appears to be at hand.

A miniature image of Sweden in the 1980s is presented by Marianne Sällström in the novel Rucklet (1992; Ramshackle). The lowest social classes dwell in a ramshackle rental, people that are ruthlessly being eradicated by a profit-oriented and streamlined rationality. The house gets new owners who want to renovate and get rid of the inappropriate lodgers. But although ‘Rucklet’ is given an elegant facade, chaotic decay remains behind the cracks in the newly-plastered walls.

In Elisabet Larsson’s (born 1940) novels Förberedelse inför besök av japan (1987; Preparations Prior to a Japanese Visit) and Bära hand (1990; Laying of Hands), the fragmented form and the free associations of the inner monologue reflect the contemporary disillusionment and splintered consciousness. Events have no single cause; people have no clearly decipherable personalities. Impressions change with the eye of the beholder and the uncertainty of memory. Larsson relativises our experience of reality and points to our inability fully to control our surroundings. ‘Identity’ therefore becomes as uncertain a term as ‘reality’.

A Modernist Expansion and Reduction of the Female Self

In the prose poetry collection Bebådelsen (1986; The Annunciation), Mare Kandre (born 1962) describes how a self is changed by an annunciation and the subsequent menstrual bleeding: “Annunciation! It is an image. It is here now. There is an angel in the room, a conception, horrible! It moves into my groin, it doesn’t find its way, it is wild and ill! Darling: there is nothing you can do – From the sexual, white lily’s cone the juice drips, the sugar, a hot secretion, and the angel is the condition my interior fears.”

In the Gospel according to Luke, the angel Gabriel appears to the Virgin Mary with the annunciation that she will conceive by the Holy Ghost and give birth to the son of God. In Bebådelsen, Mare Kandre rewrites the story. Mary is the protagonist, not God nor His son. After the visit of the angel, the poetic speaker becomes part of a female, biological inheritance that she cannot break free from, but that she can accept in a mythical manner. The poetic speaker is a variation on Edith Södergran’s haughty and expansive vierge moderne. She is a dangerous, heroic goddess with the power to foresee and affect everything. However, her exalted condition is broken when her period stops. The pregnant self is reduced, and as if out of the body of a mythical goddess, the world is born anew and the poetic speaker can go forth to meet a fellow human being: “The world takes its place within me again. Soon it will emerge, laboriously, very quietly and unknown – […]. Soon you will be here.”

With Carina Rydberg’s Den högsta kasten (1997; The Highest Caste), the female autobiography returned to prominence. Not since the 1970s had a woman’s tale of her life aroused such strong feelings in the public cultural debate. The winter of 1997 saw an intense debate about whether the writer had acted correctly, or should be prosecuted for revealing the name of the man who had betrayed her.

Mare Kandre stages the conception of identity of young girls in an intense and uncanny way. In the novels Bübins unge (1987; Bübin’s Kid) and Aliide, Aliide (1991), we follow Kindchen and Aliide into the mental and bodily chaos of puberty. Both Aliide and Kindchen battle their bodies in a violent and hateful manner, but the body is also the seat of a conflict that transcends puberty. The girls are not in the first instance attempting to break out of a stifling family, as the girls in the works of Gunilla Linn Persson and Barbara Voors are, but out of growing up itself. Mare Kandre here approaches a modernist conflict. The girls want the impossible; they want to reduce their bodies and minds to achieve a condition of absolute purity and silence, beyond the eternal cycle of life and death. They are related to Inger Edelfeldt’s mirror-twin Anorexia.

In Bübins unge, both the environment and the people are heavily stylised. This lends the narrative a mystic and archetypal character that invites a depth-psychological and symbolic interpretation. The novel is set in an overgrown garden wherein sits a house, an outdoor loo, and a well. The first-person narrator, Kindchen, lives in the house with a mother and father figure, the woman Bübin and the old Uncle. When Kindchen gets her first period, the Kid appears. She is an emaciated little girl, who turns out to be the weak and girl-like part of Kindchen that she must sacrifice in order to grow. A claustrophobic drama takes place. The self-imposed starvation and the hatred aimed at Kid is the purification process that obliterates the family ties from Kindchen’s mind, so that she may finally step out of the garden and the pent-up girlhood country.

A cosmic sense of life reminiscent of the work of Edith Södergran runs like a red thread through Mare Kandre’s suite of poems Bebådelsen (1986; The Annunciation):

Mother: I enter into it: I let it find me.

I sing the stars back into their orbits, home again.

The mountains release their heavy scents and it is real now, the insatiability, the crackling salinity of space.

I lay my head up among the heavenly bodies’ cool, wind bared bunches –

How could I ever carry it, this fortune?

Now there is nothing here I miss!

Do not expect me.

Aliide, Aliide is a kind of novel of development that depicts how Aliide handles an incestuous family trauma, and her relation to a cyclical, biological inheritance that is depicted as female. It is also a novel about how and why a girl paints and starts to write down her own story.

Aliide and her family have just returned to Sweden from a paradisiacal existence in another country. There, the girl’s ego and language were one, in harmonious union with the nature of the country and the girl’s mind. Now Aliide is forced to live in a recently built, 1970s concrete building in a world where language has lost its magical affinity with nature and with the girl’s body and mind. Aliide’s surroundings reflect the girl’s inner life. What she meets in the outer world is an image of what she experiences in her inner world. The city is a living and hateful being. Something unknown and dangerous dwells in the city, just as the memory trail of an incestuous touch hides deep down inside Aliide.

Eventually, Aliide faces what has long tormented her. Like a bulimic, she spews up the last of the dreadful experiences she has repressed, and the body can finally pull itself together. The body is purified and silent. She is emptied, benumbed, and ‘dead’.

By the end of the novel Aliide falls silent, in a passionate and persistent manner. She achieves a level of control that gives birth to writing, and she starts to write the novel of her own life. The writing preserves and silences. The bodily and perfect language she spoke in the other country before she moved to Sweden becomes a memory.

“Hunger – It doesn’t touch me! It is not like one would imagine, sour and nauseating: no, more, in the end, like a clean white salt in the body, and with this one’s interior white and scraped clean, so that it becomes it small and quiet, and Bübin, Bübin’s place becomes empty […]. Everything is displaced – The house deserted and empty! As if through a clean, green glass of grief – Denied.”

Mare Kandre: Bübins unge (1987; Bübin’s Kid)

But the dream of a language other than the everyday one lives on in the work of Mare Kandre like the image of a Utopia that has been left behind forever. In her debut novel I ett annat land (1984; In Another Country), this language is depicted as a part of the paradise of childhood. There, the girl lives in harmony with nature. The trees, the sea, and the wild animals are a perfect part of her. And in contrast to Aliide, the girl can recall nature in a satisfying way without angst-laden ecstasies. Nature ‘is’ in her painting and in her writing, just as innately as the wind ‘is’ her.

Mare Kandre gives her view not only of the importance of language, but also of the role of the poet in today’s society. In Deliria (1992), it appears that the poet should be a truth-sayer who encouragingly turns to humanity and prophesises about the world and all our futures. It is no longer a matter of portraying a young girl’s ego desperately seeking liberation, but of embracing one’s fellow human beings with the magic of language and leading them to a divinely blessed moment of insight.

Aliide becomes manic and ecstatic when she draws, unconscious of the world around her. She makes “weird, half-choked sounds […] as if she was being buried alive in her own drawing.” When she is overtaken by inspiration she gains direct access to what hides inside her; the unconscious gains an outline: “Everything that since her birth (or perhaps even further back in time than that) had lain pent-up in her body and consciousness forced itself, whenever she had a clean sheet of paper before her and a crayon in her hand, through the pale, insignificant right hand.”

Mare Kandre: Aliide, Aliide (1991)

The women in Kate Larson’s (born 1961) novels Flampunkten (1986; Flashpoint) and Replik till Johannes (1989; Reply to Johannes) also seek the absolute via a reductive pattern. They want to empty the self and be redeemed via a sacrifice that is intimately connected with their relation to men and to art. The women do not strive to find themselves for a therapeutic or worldly purpose, but in order to ascertain how the self comes into existence through its longing for love: a striving that concludes not in a fulfilment of the self, but in the opposite movement.

Gabriel and Andrea meet in Kate Larson’s debut novel Flampunkten. Gabriel bears the name of the archangel, and like him is the intermediary between the heavenly and the worldly. Gabriel is an artist, a worldly messenger of the holy. He longs to create the ultimate image of truth and beauty – the perfect woman’s face in clay: “‘I seek the woman with that face,’ Gabriel says. ‘A face which only that one woman can have. It doesn’t have to be visible. But with the clay beneath my hands and her in front of me, I shall know. The Truth. Then perhaps it will change.’”

The men in Kate Larson’s novels are self-sufficient angels. They are capable of a level of dissociation and distancing that turns out to be male creation’s prerequisite.

Johannes in Replik till Johannes is one of these angels. Through him and his mistress Disa a male and female aesthetic is crystallised. For the man, art is first and foremost form: it has no hidden or unutterable content, everything is visible. For the woman every image points to something beyond itself: “behind every word is another, whispered intent – behind every colour, another clearer one […].” These aesthetic attitudes continue in the view of woman and in her actions. Disa sacrifices everything for the sake of the angel in order to achieve holy liberation. She must empty her self, fall down in pain and self-denial, before grace can be received and a possible liberation envisaged. But she also represents the secretive and the elusive, the intimation that reality and art are not what they appear to be. The female assumes the form of the absolute and the holy.

According to Mare Kandre, the poet writes “from joy, terror, paralysed by grief, in her last hour, lacking anything else to do, in the middle of life, early and very late, in the nick of time, and so that people like me and you will find our way out of our houses, get to the water, see the end of the road, and remember where the key is buried.”

Mare Kandre: Deliria (1992)

To Tell a Story – After All

In Astrid och Ambrosius (1991; Astrid and Ambrosius), Eva-Lena Neiman (born 1955) tells a story of contemporary Sweden. We follow the fates of Astrid and Ambrosius. They live in a small mining town in the Bergslagen district of Sweden during the 1960s and 1970s, when the countryside starts to change. The young leave the town, and revolutionising crises, the assassination of Kennedy, and the Vietnam War affect people’s minds and political consciousness.

When the reclusive Ambrosius, after a life crisis, moves to Stockholm it is the 1980s. The great divide between city and country is made visible through his eyes. The modern city life is anonymous and fragmentary, while the life in the country is steeped in nature’s cyclical course, in a silence that is allowed to speak about a deeper meaning of existence. Nostalgia counters modernity and urban life. Astrid, too, ends up in Stockholm. Like Ambrosius, she is depicted as if she were of a different species – a human being of the countryside, with the quiet course of natural cycles built into her being.

Eva-Lena Neiman lets Ambrosius speak for the writer, and through him she discusses the possibilities and short-comings of writing. He is the first-person narrator of the novel and often meditates on his life, pen in hand. The driving force of his creativity is an impossible longing for something original and close to nature, which modern life dissolves. In his childhood mining town, the individual story existed; there, interplay between the individual and the surroundings was possible. The tragedy is that it is no longer possible to return because the mining community has changed, as have its inhabitants. ‘Home’ is, in the final analysis, as foreign as ‘away’. Ambrosious’s writings are born out of this feeling of exile.

“To sacrifice something for something. Your dearest possession for a value beyond such singular and dense feelings. Where was such a value to be had? Somewhere out there in the haze that was the outside world.”

Kate Larson: Replik till Johannes (1989; Reply to Johannes)

Anna-Karin Palm (born 1961), too, conducts a meta-literary discussion in her novel Faunen (1991; The Faun), but in a manner quite different from that of Eva-Lena Neiman. The latter wrote in a realistic tradition for which the individual’s relationship to the changes of society is centre-stage. She attempts to capture how an original existence has been lost, and what implications this has for the individual. Literary traditions, rather than loss and societal changes, are the focus of Anna-Karin Palm’s oeuvre. She uses the traditions to hold a dialogue with the contemporary view of storytelling.

In Faunen, Anna-Karin Palm tells three very consciously constructed stories of three different women. In London in the 1880s, we follow the Victorian author Amelia. She is writing a sentimental medieval novel about the lady-in-waiting Eleanor. One day, she is visited by a real live faun, a Roman fertility deity, who wants to help her finish her novel.

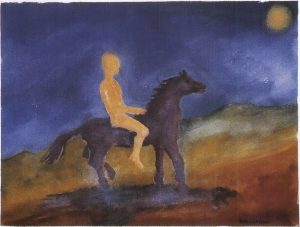

Anna from present-day Stockholm studies in London and is fascinated by a painting at the National Gallery depicting a faun. We partake of her diary entries that are woven into the narration about Amelia. In the painting that fascinates Anna, it is suggested that the faun has an equivocal relationship with women. He shows them tenderness but only if they efface themselves.

“What is it that I keep at arm’s length and that is so threatening that I must narrate all the time? Well, rapture and passion. Perhaps they look best from a distance; that they are born from distance and impossibility. When they become real, when the total moment arrives, you will always stand with a stolen gaze and scrutinise your lover’s closed face in the rapturous kiss and start the tale over once again […]. I know no other way of living. I must get through and on to the next beginning, invent until the lie sees the neck of the truth.”

Eva-Lena Neiman: Astrid och Ambrosius (1991; Astrid and Ambrosius)

The third narrative in the novel is the faun’s own story about medieval Eleanor. In this narrative, he plays the main part and attempts to lure Eleanor away from the castle where she lives and off to a mythological-erotic forest world.

“Through song I begin to experience that which trembles inside, that which vibrates inside, that which moves behind everything. And the green colour over the eyes again, billowing. Gasps in the darkness, shrieks, flashes of blood – all that I have never before been aware of. All that the castle subdues and regulates into its strict patterns. Soon I shall no longer be here, no longer be Eleanor. Soon I shall be a song in a green forest and a patch of red blood in someone else’s vein.”

(Anna-Karin Palm: Faunen).

The story about Amelia in 1880s London follows the conventions back to Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters. An omniscient narrator addresses the reader directly and in a sensible voice. The events are related chronologically and without evasion. The diary sections written in the first person by Anna are, on the contrary, associative and evasive. She uses writing to establish how and why she betrayed her good friend Rakel, whose identity seems just as hard to pin down as do Anna’s own motives. The sections about Eleanor are lyrical, take place in a mythical-mystical environment, and give the impression of being the result of a ‘free’ flow of inspiration.

These three different historical periods and styles or pastiches break against, and shed light on, each other, both thematically and in a metafictional fashion. Through them, Anna-Karin Palm enters into a dialogue with the contemporary view of literature, and formulates her own aesthetics.

The common denominator is the faun, who represents amoral instinct. He undermines the Victorian moral code, and has the ability to walk into and out of all sorts of lives and stories. The faun is the erotic textual element in the novel that destroys narratives and creates new ones according to his own head. Amelia, a personified Victorian ‘angel of the house’, is captivated by the laughing and seductive fertility god. Her conventional life is radicalised, and even her writing changes.

The faun also conquers the medieval Eleanor in the name of creative and erotic freedom. But in the faun’s version this freedom is a deadly chimera, since he is really after emptying Amelia’s narrative about Eleanor of life, laughter, and love. For Amelia’s part, the meeting with the faun entails handing him the interpretative powers over her life and work.

Birgitta Lillpers’s prose is genuinely genre-transgressing; it is lyrical, aphoristic, intellectually abstract, and philosophical, at times biblical in its elevated register. Certain sections can be read as independent poems: “Pottered about while the night deepened. Gusts, breaths from outside, blueness, smell of leaves: your cabbage, snapdragons (I have seen them stand there with a red colour so dark and intense it seems to hover and tremble a bit around the flower itself), snapdragons and garden cress. Pitch, and other tarr. I worked for a while, in a circle of light full of night airs […]. And I knew I had misjudged some things, but not everything.”

Birgitta Lillpers: Medan de ännu hade hästar (1993; While They Still Had Horses)

Thus, Amelia must resume power over her life and her novel about Eleanor. She changes the faun’s devastating aesthetics into a confirmation of storytelling and a reconstruction of the female self: “If stories are lives and lives are stories – then stories must also be able to create life,” Amelia says, and in her novel she writes Eleanor, who has officially been pronounced dead, back to life.

Anna-Karin Palm juxtaposes traditional narrative styles in a new way, but does not change their essence – an exploit which seems to be the driving force of Birgitta Lillpers’s (born 1958) novels about Gregor. The elevated, poetic prose indicates a break with both tradition and style.

In the novel trilogy Blomvattnarna (1987; The Flower Waterers), Iris, Isis och skräddaren (1991; Iris, Isis, and the Tailor), and Medan de ännu hade hästar (1993; While They Still Had Horses), Birgitta Lillpers tells Gregor’s life in reverse chronology. The last novel in the series details earlier incidents in his life than the two previous novels. In this way, Lillpers breaks the conventions of the traditional novel of development, which portrays the development of an individual over a full and linear period of time. The story of Gregor is instead revealed as a memory process. We live our lives looking forward, but only understand life when we look back.

In Blomvattnarna, Gregor lives in a small town ‘on the mountain’ and interacts socially with his grandmother and the farmer Åke. The sparsely populated environment that is depicted is just as vaguely sketched as the individual stories of the characters. The relations of people to one another, to their own development, and to objects are first and foremost constructed around the mysteriously poetic, and not around any obvious chain of events. Nothing much happens in the novels, all the drama takes place within language.

Gregor and Åke co-exist and converse quietly with each other, with themselves, and with the surrounding nature in Blomvattnarna. Birgitta Lillpers depicts two eccentrics, afraid of touch and the mutual dependence of friendship and love. Both dream about breaking up and creating another life for themselves. The existential conflict that characterises the trilogy is here carved out: to remain or break up, and does one dare approach another person without being abandoned?

When Gregor meets the sisters Iris and Isis, the goddesses of death and rebirth, he allows himself to be obsessed by love. In Iris, Isis och skräddaren, Gregor works as a tailor in an unnamed and fairy-tale-like town. The themes of departure and belonging gain another dimension in the novel. The sisters settle in Gregor’s little town for a while, but they are really on their way to Capri to die. Birgitta Lillpers details a reverse fertility myth. During the winter, the goddesses live in the tailor’s town, but when spring approaches they must die: “Settled, on their way to the place of their death. Such a quiet journey.” Birgitta Lillpers’s characters are all involved in the same process of immobile movement, heading for death’s final reckoning.

In Medan de ännu hade hästar, the themes of solitude and love are more dramatic and dark, and deepen the depiction of the previous novels. Gregor, known here as the Brother, lives in a marriage-like relationship with his brother Lauritz. The biological and essentialist gender framework is dissolved, and the status of masculinity and femininity as role playing and convention is emphasised. Lauritz assumes the role of victim. He bears the burdens of others and gives his love without any return. The Brother is the egotist, who demands love and attention – and therefore always gets it. The brothers play a dangerous game with each other that ends in Lauritz’s presumed suicide.

In the faun’s tale of Eleanor, where he himself is the protagonist, he brings her out of the conventional order and into that of the forest and of amoral nature. ‘She’ becomes a lyrical rhythm closely affiliated with the body and the unconscious, or a mysterious pre-linguistic stage, which in the feminist theories of the 1980s was often connected with ‘the female’.

The life story that Birgitta Lillpers depicts in the novels does not go from uncertainty to insight, and has no real beginning and no traditional end. The immobile and charged ‘now’ of poetry breaks against Gregor’s continued searching, eternal departure, and changing roles in the novel. What plays out is not the development of Gregor as an individual, but rather a continued reduction of identity that is constantly recharged by the mystery of the lyrical tone.

“Found a faun today at the National Gallery. Went there longing for a picture instead of words and was spellbound right away by this faun. He sat there, in one of the small rooms to the left, tenderly bent over the prone, dead woman. His one hand gripping her rounded shoulder, the other lightly, lightly touching her brow […]. He is kneeling with his cloven hooves prettily folded beneath the hairy thighs; his gaze melancholy and amazed.”

Anna-Karin Palm: Faunen (1991; The Faun)

Translated by Marthe Seiden