“Maternal love is history’s most exploited emotion, not only in the individual case but also in a social perspective”, Eva Moberg wrote in a much-noted article, “Kvinnans villkorliga frigivning” (Women’s Conditional Release), in 1961.

Inspired by Simone de Beauvoir’s Le deuxième sexe (1949; Eng. tr. The Second Sex), she takes the stance that would become dominant in the women’s movement in the 1970s. “Both men and women have one main role, that of being human”, she writes polemically against the opinion established in the wake of Alva Myrdal and Melanie Klein that a woman has a ‘double role’. Moberg attacks the prevalent biological determinism, in which a number of societal functions are coupled to biological motherhood: “Basically, there is no biological connection between giving birth and nursing the child, and the function of cleaning its clothes, making its food, and attempting to raise it to be a good and harmonious person. Not to mention the function of scrubbing floors, sewing clothes, going to the grocery store, and polishing the furniture.”

Just as in the women’s movement of the 1970s, Eva Moberg’s criticism of the maternal role was linked with an attack on the stay-at-home wife. “To my mind the option of marriage as an institution of maintenance must be completely eradicated”, she writes, and the criticism of a society that exploits woman’s work in the home without paying for it is paradoxically turned against the home-making women and their supposed parasitic and passive lives. “The only women’s role that is no longer valid is that of the stay-at-home wife”, writes Jytte K.-O. Bonnier, as one of the period’s few gainsayers, in 1975. She finds that the care work has been set aside and asks, with clear reference to the tradition from Ellen Key and Elin Wägner: “Would not the larger family, the work place, benefit if woman brought some of the inheritance from the stay-at-home life along with her from home?” Similar thoughts are found in Ulla Isaksson’s (born 1916) novel Paradistorg (1973; Paradise Square), which also prompted massive opposition from the leading feminist critics. In a collectively written article in the Swedish daily Dagens Nyheter in 1975, Maria Bergom-Larsson and Eva Adolfsson, among others, attack her for “crusading for holy motherhood” in Paradistorg.

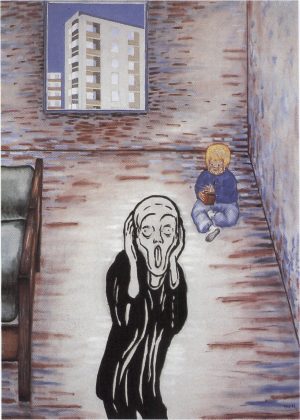

In Paradistorg Ulla Isaksson discusses the unloved and destructive children. “The Aniara-children” she calls them, in reference to Kristina Brandt Humle’s dissertation on young criminals. The novel has three older women at its centre: the rational, distanced, and well functioning teacher Katha, her best friend Emma, very clearly moulded on Ellen Key and constantly preaching children’s rights and the mother’s duties, and the uneducated Sara, the servant girl who very quietly takes care of the everyday basics. Emma, who finds that those women who leave their children at day-care centres “are worse than Lieutenant Callay at Song My and President Nixon at Christmas 1972”, was seen by the critics as the author’s mouthpiece. But the writer’s sympathy for Emma is limited. She is clearly an imperious person, unreasonable and depressive, she drinks too much and has, in spite of her ideology, herself had an abortion. On the one hand she has a warmth and empathy that the rational Katha lacks, but on the other hand she is emotional in a self-destructive measure, just like Sara, who cannot handle the cruel reality when she finally discovers it, but suffers depression.

There are no women heroes in Paradistorg (1973; Paradise Square). Rather, one can say that Ulla Isaksson plays the three women’s attitudes off against each other; three polished facades that are all brought to crack during the summer of the novel’s time span. The novel’s message is hardly a single one. Rather, it elucidates the women’s dilemma. The final image, where Katha sits with a broken face and the “Ainara-child” King, the snake in paradise, on her lap, while her son-in-law cuts down the nephew who hung himself, also indicates that there are many different victims. In Katha, Ulla Isaksson depicts the limits of the new rational motherhood, the supremely competent professional woman who was the ideal of the 1970s. Paradistorg is a disconsolate book where hope is not found amongst the women – Grupp 8 (Group 8), Sweden’s leading women’s organisation during the 1970s gets several polemic mentions – but in one of the novel’s men, the cranberry farmer Puss, who is the only one in this metaphor for the Swedish idyll who has a strong and uncomplicated ability to empathise.

With the novel Paradistorg, Ulla Isaksson did not just land in the middle of the women’s movement debate. The novel can be read as a part of the debate on crime and the treatment of young criminals that was ongoing in Sweden during the 1960s and 1970s. “Paradise Square is no Skå”, the protagonist Katha says with direct reference to the children’s correctional ward built like a village, Skå, which came to symbolise the new direction in the debate about the treatment of criminals, where a loving community rather than disciplinary measures were what counted. The man behind the effort, Gustav Jonsson, soon known as Skå-Gustav to the Swedish people, had a huge impact with his message of love, not least thanks to female journalists like Kerstin Vinterhed.

Ulla Isaksson, Love’s Intercessor

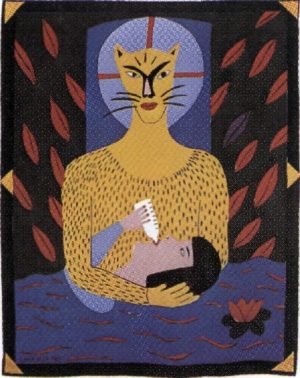

At the time of the debate, Ulla Isaksson had a long and important authorship behind her, wherein maternity had been a recurring theme. Motherhood, giving birth, but also the love between mother and child are some of the intensity-packed, almost ecstatic, liminal experiences Ulla Isaksson keeps using in her writing. The meeting with God and love between man and woman are the other two.

As opposed to the dominant part of the modernism of the 1940s, for Ulla Isaksson God is not absent. He is very much present and active, both in the world and in human relations. Her second novel, the highly charged domestic drama I denna natt (1942; In This Night), includes a traditional love triangle where a woman wavers between two men, but also a triangle where a mother stands between father and child. The dominant triangular relationship, however, is one in which God is the third and decisive factor between man and woman. In Ytterst i havet (1950; Uttermost in the Sea), Ulla Isaksson’s fourth novel and her breakthrough, the search for God reaches its culmination, and from then on holds only secondary importance in her oeuvre. Love and motherhood problems are constantly reloaded and often stand opposed, as in De två saliga (1962; Two Blessed Ones), the magnificent novel about the psychiatrist Christian Dettow and his wife.

In an article in the Gothenburg daily Göteborgs-Posten in 1979, Ulla Isaksson discusses the limitations that the woman’s role – and her acceptance of it – has had on her authorship, and she uses the novel Ytterst i havet as an example: “When at the close of the 1940s I wrote a novel about the crisis of faith I had just fought my way through, I chose to bring it to a male publisher – a Free Church preacher”, she writes and italicises: “There really was no other way!”

“But never, never will I forget this moment. Never!” Cecilia says in Ulla Isaksson’s manuscript for Ingmar Bergman’s film Nära livet (1958; Eng. title Brink of Life) when she wakes from the anaesthetic after a miscarriage. ”This close, you see, Sister, I will never be this close to life again … It has passed right through my fingers, through my womb, as if it were water. Like water that leaves no mark behind.” In Nära livet three very different women meet in a hospital ward, and during the days and nights of the film the women’s mixed feelings about giving birth are laid bare with almost scientific accuracy. There is longing and terror, a feeling of being subject to life and to the husband, of being victim and at the same time being the one who carries new life in her body.

In Ulla Isaksson’s works there are two forces of nature influencing a woman’s life. One is love for a man, the other is motherhood. But where the man is always welcomed in joy – although often mixed with pain – the feelings towards an expected child vary greatly. In the short story collection Kvinnor (1975; Women), in which Ulla Isaksson has gathered bits from previous novels to form something that resembles a female portrait gallery, one finds Maj-Britt who denies her pregnancy until the penultimate month and cherishes an intense hope that the child will die, if not before then after the delivery. “Kill it, don’t you see that you must kill it!” she exclaims. Maj-Britt is clearly a relative of Hjördis from Nära livet, who is disgusted by the child within her and does everything to abort. One night when the boy is screaming Maj-Britt strangles her child, while the retarded Rosa in the novel Kvinnohuset (1952; House of Women), peopled by nothing but loving women, completely loses touch with reality during pregnancy and takes her own life.

Motherhood is an uncontrollable drama in Ulla Isaksson’s works. The woman is alone with immense forces released inside her. The man, like Stina’s husband in Nära livet, can worship the mother, but he is helplessly excluded, and often, like both the other men in the film, he does not want children. He is too stingy, like one of the men in Kvinnor, or more commonly, he is afraid to share the woman with someone else, like Christian Dettow in De två saliga, in which the wife chooses to abstain from the child she longs for in order to preserve the love relation with the man.

The pain spot relative to motherhood is continually displaced in Ulla Isaksson’s oeuvre. Whereas the early novels are written from the expecting or recent mother’s perspective, the later works deliberately focus on the ageing mother. Without flinching from the phallic traits of control and superiority in motherhood, Ulla Isaksson, like none other in Swedish literature, depicts the aged mother’s abandonment and anger in a culture that hands all power to the child, and where the daughters seems predestined to turn against their mothers. In the novel Klänningen (1959; The Dress), Isaksson approaches the subject for the first time and in the novel FödelseDagen (1988; The BirthDay), the theme culminates in an intensely sensitive narrative, in which the abandoned mother literally dies of rage.

Ulla Isaksson is a writer of strong emotions, and the great sin in her works is a lack of love, regardless of whether it is in relation to God or men or women or children. When Anna in Kvinnohuset once again takes back her husband and comforts him after yet another affair with another woman, she does it with all the care he is used to. After the act of love, however, she strangles him, and when she turns herself in to the police she reproaches herself for her inability to love unconditionally. “If I had just loved him more, if I had just had enough love …”

For Ulla Isaksson total devotion is the goal, and while not shying away from its sickly and megalomaniac expression, she readily attaches great importance to its transformative power, which encompasses not only the individual but all of society. In her only historical novel, Dit du icke vill (1956; Where You Do Not Wish to Go), Hanna from Lustiggården (Funny Farm), who has been accused of being a witch, but whose execution has been stayed because of her strong disavowal, must face her real sin, a lack of love, and she returns to her family chastened and with a more open heart.

In Dit du icke vill it is Hanna’s strength of will and her husband’s love that saves her. God gives no guidance. He has fallen silent. As early as in 1950, in the novel Ytterst i havet, the search for God, which was the driving force in the early part of Ulla Isaksson’s works, culminated. One sees how the three female longings and conditions of bliss charging Ulla Isaksson’s writings – the meeting with God, the child, and the husband – are now filled with complications, turned inside out, and carried to extremes one by one. In FödelseDagen, at the end of the 1980s, motherhood has been transformed into a raging dispute, in which the good mother sees herself as a distorted image in the eyes of her daughters, and the appalling reflection rends her asunder like the giant in the tale. In the autobiographical Boken om E (1994; The Book about E), the hitherto unwavering faith in love’s power to make things right is finally shaken. In narrating how her husband walks into dementia, Ulla Isaksson reaches the borderland where love turns to helplessness.

The Mother as Muse

Criticism of the mother’s role grew even stronger during the 1970s, but in several of the more interesting autobiographical books from the late 1970s and early 1980s one can discern the opposite movement. In Sun Axelsson’s (born 1935) Drömmen om ett liv (1978; Eng. tr. A Dreamed Life), as in Kerstin Bergström’s (born 1934) Parkeringsplatsen (1976; Parking Lot), Kerstin Strandberg’s (born 1932) Skriv Kerstin skriv (1978; Write, Kerstin, Write), and Margareta Strömstedt’s (born 1931) Julstädningen och döden (1984; Christmas Cleaning and Death), the daughter reaches out to a lost mother in impotent longing and attempts, like Orpheus concerning his beloved Eurydice or the goddess Kore concerning her lost daughter Demeter, to sing her back from the underworld.

In the women’s literature of the 1970s the autobiographical slips into the fictional and vice versa. Ambiguous presentations are the rule rather than the exception. “Novel”, says the frontispiece of Sun Axelsson’s otherwise strictly autobiographical Drömmen om ett liv (1978; Eng. tr. A Dreamed Life). “Prose narratives”, Kerstin Bergström called her books. Not until they were reissued in the omnibus volume Ett halvt liv (1988; Half a Life) did she tell her readers that the stories were from her own life.

In Äppelblom och ruiner (1980; Apple Blossoms and Ruins), Marianne Ahrne uses fictive and documentary traits. The designation “novel” on the frontispiece is combined with an exposition that at first appears to be a report from the Swedish mental health department. A closer reading of the story about the writer’s meeting with the schizophrenic Rune transforms the case file to a love story, which in turn takes on the guise of autobiography when the Marianne of the narrative meets herself in the other.

In these narratives the mother is painfully absent and the traditional distribution of roles between mother and daughter has been turned on its head. The daughter is the nourishing caregiver, the mother like an unreasonable child. In Margareta Strömstedt’s Julstädningen och döden, the daughter keeps trying to get her mother out of bed so she can help her get dressed. She cleans and washes and sweeps to make it possible for the mother to enter the family circle, but in recurring catastrophic scenes she time and again finds that her labours are in vain. Here, it is the child – not the mother – who carries the responsibility, and the daughters in these narratives always feel obliged to make further efforts.

“I failed”, says Kerstin Bergström in Parkeringsplatsen, when the girl does not want her mother along for her graduation party. “The graduation party was decisive and I fell through. I failed. I did not dare. / […] / She was in the living room, but she came to see me before I left. I remember her eyes and I loved them, but for the first time I felt calmly and clearly that I didn’t dare to love her.” In these narratives the mother has abandoned her daughter – she has been sick, and died when the girl was little, as in Sun Axelsson and Kerstin Strandberg, has disappeared into alcoholism as in Kerstin Bergström, or has simply just taken to her bed in impotence when faced with life as in Margareta Strömstedt’s Julstädningen och döden. She has turned away from the child, but continues to be a source of pain and guilt that blocks life for her daughter. In Sun Axelsson’s three autobiographical novels, the memory of the mother lingers in the protagonist’s body tremors. She has had them since just after her mother died, and they recur in all situations of crisis and helplessness as a reminder of her utter vulnerability. In Kerstin Strandberg’s novel Annemonas gördel (1990; Annemona’s Girdle), where she once again describes a motherless daughter, the daughter is unable to remember or speak of the death of her mother, since she is, to quote from the novel, “locked away in a dead mother”.

“For some years I had forgotten everything. I remembered little fragments of the past and made up the rest in my imagination”, Sun Axelsson writes in Drömmen om ett liv. “I don’t remember”, says Kerstin Bergström in Parkeringsplatsen. “What I had dwelled on was, in our language of lies, called ‘Silence’”, Kerstin Strandberg writes in Skriv Kerstin skriv. The writers suffer from a memory they no longer have access to, but which must be integrated for life as well as writing to become possible.

“Now they have invented a term for books like this one: ‘confessional literature’ it is called, if written by women”, Sun Axelsson writes in Drömmen om ett liv. Her rage is unveiled, as is that of many other women writers.

“Brave, uninhibited, occasionally amusing confessions have been degraded to ‘private mental masturbations’. Universal everyday realism and criticism of society are wanted”, Kerstin Bergström writes in Rollen (1977; Role), in fury over the criticism levelled at women’s autobiographies, and the label ‘confessional literature’ became a pejorative. “Historically, it corresponds to the expression ‘the female literature of indignation’ used in the 1880s about, among others, Victoria Benedictsson’s Pengar (1885; Eng. tr. Money) and Amalie Skram’s Constance Ring (1908; Eng. tr. Constance Ring)”, Kerstin Strandberg finds in Klotjorden 1980 (1980; Globe of Earth 1980). “It was a hair-raising attack attempting to indicate that they didn’t write because they were artists, but because they were upset.”

In Kerstin Strandberg’s Skriv Kerstin skriv the self actively represses all memories of the mother. “My mother died on New Year’s Day 1944; in the thirty pages I have from the years 1946-1950 she is not mentioned once. In my diary from 1944-1946 I write specifically about her once and on one occasion I mention in passing that I, for a costume party, had dressed in ‘mother’s rags from the attic’.” During the writer’s block that seized her after the two acclaimed novels Som en ballong på skoj (1967; Like a Balloon for a Joke) and Klotjorden (1970; Globe of Earth), the tension before the third novel becomes too strong, and she can only get through it by writing about the silenced and repressed memories. To write forth their memories and their mothers is an act of identity-healing for these writers. “Here am I now. Be proud of me, Mother!” Sun Axelsson writes at the end of Drömmen om ett liv. “My white sheets are covered in writing / And I am free” begins the poem that ends the last part of Kerstin Bergström’s autobiographical trilogy Parkeringsplatsen, Rollen (1977; Role), and Resan (1978; Journey): “Free from the Roles and the Rules / I am free from Her / whom I can’t bear to remember.”

As in psychoanalytic theory and in the methods of consciousness-raising within the new women’s movement, narrating an event, the very act of putting it into words, is accorded a liberating function in these books, and they stand out as turning points for the respective writers. For Kerstin Bergström, it was a late debut, the beginning of what was to become an extensive authorship. Kerstin Strandberg’s Skriv Kerstin skriv and Sun Axelsson’s Drömmen om ett liv are two literary comebacks and public breakthroughs. With Julstäd ningen och döden Margareta Strömstedt, who has been a productive and appreciated children’s writer since the beginning of the 1960s, enters a new phase in her authorship.

Kerstin Strandberg and Sun Axelsson made their debuts within the modernist tradition during the late 1950s and 1960s respectively. Around 1970 they fell silent, and the autobiographical narratives are not just an attempt at reconnecting with a lost memory and a repressed identity, but also a reclaiming of a lost authorial voice. The thoroughly distanced, playful, and ironic style that both Sun Axelsson and Kerstin Strandberg employ in the first phase of their authorships is, in the 1970s, replaced by the autobiographical books and their direct address. The despairing sense of alienation in Sun Axelsson’s collection of poems Mållös (1959, Speechless), and in her novels Väktare (1963, Watchmen) and Opera Komick (1965, Comickal Opera), was displayed in allegorical terms and became personal through an elaborate use of irony, just like the impotence and loathing of life expressed by Kerstin Strandberg in her satirical novels Som en ballong på skoj and Klotjorden.

“LOVE UNKNOWN / DEATH NOT GRASPED / LAUGHTER A DISEASE”, says the frontispiece to Kerstin Strandberg’s Klotjorden. It is an apocalypse where horror is added to horror in an almost unbearable stretch of grotesques, harshly penned and sarcastically cut out with such care that the text is occasionally altogether impenetrable. In a commentary to the novel published by Kerstin Strandberg ten years later, Klotjorden 1980 (1980; Globe of Earth 1980), she points to the key meaning of the last chapter: “By the way, it isn’t intended that Anna Virginia should be close to you.” Klotjorden was a text with two purposes, she writes. She wanted to change the world, but she also wanted to relate an experience that weighed on her. And whereas the universal and impersonal is brought to the surface in 1970, she points to the underlying, very private story in 1980. In many ways she seems to argue that the wildly fantastical satire is used to cover her own painful narrative. She was stuck, she writes in Skriv Kerstin skriv, in the modernist tradition’s paradox: “speak – don’t speak”, and was silenced by the contradictory demand for the writer’s absolute honesty on the one hand and the demand for universal themes and objectivity on the other hand. She systematically cleansed her texts of anything that might make her person visible, and used irony and fantasy to lift them to a level of abstraction that would keep them from being besmirched by the experiences they had arisen from.

While Kerstin Strandberg in 1980 re-reads her own 1970 novel Klotjorden (1970; Globe of Earth), she also reads Åsa Nelvin’s novel Kvinnan som lekte med dockor (1977; The Woman who Played with Dolls), and in this meeting of texts she finds revealed the narrative she so carefully attempted to hide in her own text. “It is about the same sort of blind passion”, she writes. “Åsa Nelvin shows a woman who can’t handle deeply buried disruptions and instead covers them with ‘love’. She escapes the real problem, just like the alcoholic who only engages himself and his surroundings in issues that have to do with drinking or not drinking.”

“I once told a story about Chile. I told of cities, seas, and volcanoes. People passing through my narrative entered and left again with a nod. I told of wild dogs and Araucans. I no longer know what I told of”, Sun Axelsson writes about her travel journal Eldens vagga (1962; The Cradle of Fire), in the third part of her autobiography, Nattens årstid (1989; Season of Night). When Sun Axelsson was first published as a poet in 1959, she was in Chile. She had gone there to reunite with a man she had lived with in Stockholm. While there, she realised that his love was very limited. She had to take care of herself in a strange country, and in Nattens årstid (1989, Season of Night) one can read about her illness, terror, and vulnerability. In the well-received travel journal she wrote in connection with the journey, on the other hand, the private story is, in spite of a very personal narrative approach, hidden beneath a distancing and humoristic surface.

The narrative is double, and in the autobiographical books Sun Axelsson also works with a dual aesthetics, by shifting between two completely opposed voices, one near and direct and intimate, and one distanced and ironic. The young woman at the centre of all her books, right from the debut through the autobiographies to the latest novel, Tystnad och eko (1994; Silence and Echo), is also plagued by duality. Outwardly, she seems happy, competent, and well adapted, yet within she is a wailing child. She is: ”someone who would hide and yet wants to be seen. Someone who wants to reach people and who wants to escape the dangerous humans. Someone who wants to love humans and yet someone who would always fear and distrust them”, as she writes in the second part of the autobiography, Honungsvargar (1984; Honey Wolves).

“I toiled to become a fallen angel, dangerous. Exciting, disillusioned”, Sun Axelsson writes in the second part of her autobiography, which takes place during the 1950s. What marked this post-war generation was desperation, she finds. “For me the fifties were an entire generation that lived as if life were war, the war it well may be, the war of life. They didn’t spare themselves anything. There was utter grief and joy over every roof.”

“I become – now and every time – two”, Kerstin Bergström writes in Parkeringsplatsen, when she finally confronts the memory of her mother’s drinking problem and outgoing sexuality. And her narrative is also aesthetically fragmented. It is, just like the two following parts Rollen and Resan, run through with ellipsis and circumventing manoeuvres. The most traumatic memories are described though non-description, indirectly and with poetic license. Breezes blow through the house. The piano plays. There are no first names in Kerstin Bergström’s autobiographical narratives. They are about “Her” and “the Girl”. Humans as well as things and events become existential quantities within the story, which can hardly be told and which keeps splitting in two. Fragmentation is built into the poetically dense and warm tale about life before the breezes, when the doors stood open and the house smelled of freshly baked bread. And it is constantly torn by a coolly distanced voice that makes it shatter into contradiction and mystery.

Kerstin Bergström’s first novel, Svek (1983; Betrayal), is an echo of the autobiographical childhood story of the girl with the alcoholic mother, yet is transformed into a saturated story in which the blanks are filled in and the narrative has been given a logical end with the girl’s suicide. Death is a constant presence in Kerstin Bergström’s works, and in the novel Tveljus (1990, Double Light) Kerstin Bergström once more tells of a woman living in constant fear of death. In this book it is not fear of what may happen to her mother or herself, as in previous books, but of what will happen to her daughters. In book after book she builds the narrative started with the autobiographical trilogy into new significances, and in Boken om Henne (1988; The Book about Her), she returns to the mother and attempts to tell the story from her perspective. She re-crosses her landscape, both the concrete, white expanses of snow in the North and the inner existential landscape, always along new paths, precisely as do Sun Axelsson and Kerstin Strandberg.

” Yearning is the dated expression that best describes her wish to narrate the drama of her life”, Kerstin Strandberg writes about Henrietta in Undangömda berättelser (1995; Hidden Stories). This yearning saturates her own writings. Occasionally she acts as if carefully taking inventory. With the uttermost care she describes the objects of her childhood world, which – luminous, loaded with grief, but inaccessible and basically incomprehensible – have to be constantly reinterpreted.

As early as in the debut novel’s tale about the Hospital of Mediocrity and the Outpatients Department of Sorrow, the worker’s residency in the city of Lund called Nöden (Need) is clearly recognisable. It has lived up to its name for Kerstin Strandberg and many others, and with each text she uncovers new aspects of this place as well as the experiences she had there. A young woman from this neighbourhood is the focal point of her novels. Virginia in the debut Som en ballong på skoj, who becomes Anna Virginia in Klotjorden, to return in the third novel, Som en vindil efter sanningen (1984; Like a Breeze after Truth), as Sanna (true) Virginia. In the fourth and so far last of Kerstin Strandberg’s novels, Annemonas gördel, she has obtained the down-to-earth, non-allegorical name Anna. The woman in these narratives is, like the pain, the same and yet changed. The innocence signalled in the early name must be continually lost, and the truth, which is this woman’s goal, must always be re-examined.

Margareta Strömstedt’s two novels, Julstädningen och döden and Församlingen under jorden (1990; Underground Congregation), are likewise continued examinations of a very specific and autobiographically-anchored landscape. The first novel is about the daughter and her distant mother. In the next novel, Margareta Strömstedt shifts the focus to the younger brother and the theme gains a new dimension. In Julstädningen och döden the little brother stages a vigorous rebellion in the Småland preacher’s family, and in the almost physically painful narrative of the protagonist’s exertions to get the family to function he appears to be her secret joy when he, both literally and figuratively, swears in church.

“The more I worked with the older girl the more the little one budged in: Don’t forget me! Tell them about me too!” Margareta Strömstedt writes in Svensk Bokhandel (The Swedish Book Trade) in 1982, and during the following decade she writes the children’s book series about Majken. The five books tell of a very curious and independent little girl. Majken’s fantasy life is so strong that it almost moves mountains, which she well may need since she, just like the girl in Julstädningen och döden, has a mother who cannot cope.

In her children’s books about Majken, Margareta Strömstedt writes two very strong wish-fulfilment stories about her mother, and in both she gives the mother great power and much love. In the first, Majken nearly drowns and the mother finally gets out of bed. “I see before me how mother rushes up and in less than two minutes her hair is arranged and the coat on and hurries off crying: ‘My darling daughter, nothing must happen to my darling daughter!’”.

The other dream lets the mother leave the home and become a missionary in Africa. There she finally gets the recognition she deserves, and the daughter writes with great satisfaction: “She will never have to feel afraid again. I can’t help thinking about it: SHE WILL FINALLY KNOW HAPPINESS IN HER LIFE.”

In Församlingen under jorden his rebellion changes to powerlessness, and the narrative of neglect deepens. The family’s house must be renovated, the older sister has moved to Lund to study, and the mother and father rent a house in the next village. The younger brother stays behind on his own, and interrupted phone calls run like a refrain throughout the novel. Mother and father forget to leave their phone number and when they call they just pay for a while before the line is automatically cut off: there is buzzing and shouting without anyone getting through to the other. The village exchange keeps informing him that the sister in Lund has called while he was out. And if the younger brother was the elder sister’s rebellious alter ego in Julstädningen och döden, in Församlingen under jorden he is even more her impotence and inability. He is the encounter with the emptiness and the darkness that the elder sister has left behind. He is the outsider position and the naked sincerity that the daughter was never able to allow herself.

Translated by Marthe Seiden