“Poignantly young” the publishers called Birgitta Järvstad’s (born 1934) young adult novel Väg mot i morgon (Heading for Tomorrow) when it was published in 1961. Young is the key word. The intent of the series of pocket books wherein the novel was published was to give “young people books that deal with their own problems and their own reality”. The will to solidarity with the young reader characterises Swedish children’s and young adults’ fiction throughout the 1960s and 1970s. There was a striving to create an ”address on an equal footing” and to articulate the problems of adolescence. The first-person narrator writes her experiences during or after a crisis, and the act of writing itself functions as a kind of therapy. In the words of the leukaemia-suffering Annika Hallin in Gunnel Beckman’s (born 1910) breakthrough book Tillträde till festen (1969; Admission to the Party): “The letters march forth and form into a sort of guarding rail between me and the snake pit.”

With her autobiographically-founded diary trilogy about life between the ages of ten and fifteen, launched by Jättehemligt (1971, Super Secret), Barbro Lindgren (born 1937) created her very own style of narration that may almost be considered naivistic. It has a combination of intimacy and distance in its narrative code with roots back to J. D. Salinger’s influential novel for young adults, The Catcher in the Rye, 1951, but many writers of fiction for young adults in the 1960s and 1970s, female as well as male, replaced the male narrator with a female.

Väg mot i morgon, whose narrator is a young woman during her last year in high school, is a text that is saturated by the complex problems of female adolescence: the fear of being controlled by the male gaze paired with the fear of “becoming like mother”. This specific theme, the liberation from the mother, recurs in several later young adult books. The most outrageous characters are found in the work of Maud Reuterswärd (1920–1980) and Maria Gripe (born 1923); for them the menstruating mother personifies the destructive forces in the family. Maud Reuterswärd, like Maria Gripe, was inspired by the British psychiatrist R. D. Laing and his theories about the ‘schizophrenogenous’ (in the sense of ill) nuclear family, and the mother is often seen as the problematic figure. This is particularly clear in the books about Elisabet, in which the mother makes a desperate suicide attempt in Ta steget, Elisabet (1973; Go for it Elisabet), and a really horrible mother is found in the later book Flickan och dockskåpet (1979; The Girl and the Doll’s House).

The father conversely becomes the daughter’s ally in the adult world. In Birgitta Järvstad’s Väg mot i morgon, the mother has an extramarital relationship and the father soon takes on the role of counsellor and role-model, even when it comes to sexuality – a role that changes in later young adult books. Masturbation and birth control are spoken of openly, and the sexual liberation culminates in a poetically narrated act of love. In this, the first depiction of sexual intercourse in the history of Swedish young adult fiction, love is not just given body, but also soul. The really new thing is the undisguised female passion, the explicitly stated desire for the man.

Birgitta Järvstad’s Väg mot i morgon broke down some of the taboos that young adult novels had been marred by, mainly regarding sexuality and death. The young protagonist’s boyfriend dies in a traffic accident. But the novel also points to the problem-oriented depiction of society that would dominate young adult literature during the 1960s and 1970s. Here, the reader finds the later standardised circle of motifs, including love, death, and family disintegration combined with the teenager’s high-strung self-centricity and existential dread, all depicted from a ’young’ point of view.

Towards the middle of the decade, young people’s search for identity was related far more to a politically-oriented complex of problems. Awareness of the problems of the world (the war in Vietnam, the oppression of the third world) and the seamy side of the Swedish welfare state shapes the foundation for depictions of generational conflicts and distrust of authority. Titles such as “Vart ska du gå?” “Ut” (1969, “Where are you going?” “Out!”) by Kerstin Thorvall and Är dom vuxna inte riktigt kloka? (1970; Aren’t Adults Supposed to be Sane?) by Clas Engström expose the writers’ striving to identify themselves with the young generation. An address on an equal footing was generally applied, and they consciously addressed both genders. Gender-divided young adult literature, with roots in the girl and boy book tradition, was to be buried for good.

In a newspaper article the illustrator and author Kerstin Thorvall (born 1925) settled with the traditional male and female roles in books for smaller children. “Do all children’s book authors live in Fairyland?” she asked in Expressen, 29 June 1965, and the debate that followed was the start of a more gender-conscious scrutiny of literature for children and young adults. But Kerstin Thorvall had already updated the gender issue with her trilogy about Lena, begun with Flicka i april (Girl in April), 1961. The story of a girl from the country who, with an equal measure of dreams about love and career in her luggage, comes to Stockholm to train to be a fashion designer has its basis in Kerstin Thorvall’s own life experiences. In the third book, with the telling title Flickan i verkligheten (1964; The Girl in Reality), the eternal conflict between work and motherhood is debated.

In her later young adult books Gunnel Beckman scrutinises conflicts and meetings between various generations of women, and she also weaves in historic flashbacks to the woman’s cause. But it is with Tillträde till festen (1969; Admission to the Party) that she made her most significant contribution to young adult female literature.

The ambition to create a forum for a dialogue in the name of gender democracy is marked in several of the period’s books for young adults. It culminates with Gun Jacobson’s (1930–1996) Peters baby (1971; Peter’s Baby), which resolutely turns gender roles upside down. In this obviously much-read book, it is the teen father who is ’abandoned’ and has to take care of the baby.

In theory, the dream prince Mikael in Kerstin Thorvall’s novel trilogy about Lena subscribes to equality, but as a real man he finds it hard to swallow his wife’s professional success. When Lena becomes pregnant, he remarkably swiftly and willingly takes over the role of provider for the family. A bright and equal future does not seem to be in the cards, and the pessimistic ending rather indicates the coming gender battle, although with some caution: “Lena saw it like a vision right through Mikael’s face. What if she was the one offered a better job at a more lucrative salary? If she was able to say to Mikael: ’Don’t worry. I will take care of this. You don’t have to work.’ – How terrible would that not be?”

Gunnel Beckman (born 1910) is one of the women writers who refined a more specifically female discourse. In Tre veckor över tiden (1973; Three Weeks Late) and Våren då allting hände (1974; The Spring Everything Happened), she writes about topics such as unwanted pregnancy and abortion. In Gunnel Beckman’s texts one also finds a new creative aesthetic attitude to language. It is often bombastically rich in imagery and loaded with symbols and connections to a women’s literary tradition of imprisonment metaphors: the doll, the doll’s house, and the fairy tale princess. Sleeping Beauty is a particularly cherished figure in the female text of young adult literature.

In Tillträde till festen the gender rebellion is intricately woven together with an identity crisis. The book quotes a passage from Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, 1963, which had been translated into Swedish the previous year. The quote treats of ’identity crisis’ as defined by the American psychoanalyst Erik Homburger Erikson: “the period in life when every young person must gain perspective on him- or herself” and integrate the remains of childhood with the expectations for adult life. Above all it is necessary to find ’a coherence’ between an insight into oneself and a growing consciousness of the expectations of others. For the nineteen-year-old narrator who in Tillträde till festen reads Friedan – and thus gets Erikson’s definitions as well – this insight becomes of crucial importance. The analysis of the self at the typewriter becomes a path to the ’coherence’ that Erikson speaks of, and that became so essential in the 1970s new ’female’ young adult literature.

More purely feminist young adult books combined with literary ambition were and are rare. For smaller children, the writer and woman’s cause debater Barbro Werkmäster (born 1932) and the illustrator Anna Sjödahl published the manifesto Visst kan tjejer (1973; Of Course Girls Can), a book that, according to the writer herself, attempted to translate the woman’s cause to the world of the child.

Boel Westin

Translated by Marthe Seiden

Childhood in the Modern City

Anne-Cath. Vestly (1920-2008) was one of the great contemporary Norwegian storytellers. Her works reflect the huge social changes that took place in the last half of the twentieth century from the perspective of families and children.

Anne-Cath. Vestly’s children’s books had a unique impact – first through radio and later in TV programmes and on film. With more than forty book titles – translated into seventeen languages – and more than six hundred radio broadcasts, she influenced Norwegian children’s reading and listening for several decades. It started with the radio programme “Barnetimen for de minste” (Kid’s Hour for the Youngest) in 1951-52. Anne-Cath. Vestly, together with Alf Prøysen and Thorbjørn Egner, became the leading storytellers in this new medium.

In 1953, the first stories were published in the book Ole Aleksander Filibom-bom-bom,which marked the beginning of a series of books about Ole Aleksander, a little boy who grew up in a block of flats in a suburban town. While the setting represented a new reality in Norwegian children’s literature, thematically and formally the stories were built on the tradition from Dikken Zwilgmeyer (1853-1913), Barbra Ring (1870-1955), and Marie Hamsun (1881-1969). The central focus of this tradition was the upbringing and social conditions of children, and the trend was clearly positive socialisation.

However, Anne-Cath. Vestly’s entire body of work can also be read as an exploration of the new rootlessness of children and adults. At the centre is Grandma – an old, naive figure who was introduced as early as 1957, and who is still very much alive in the 1990s. However, she is not a traditional grandmother. Our grandmother is always on the go, while at the same time attempting to build new secure relations. The “natural” family with the homemaker mother and the career father no longer exists. The princess in Lillebror og Knerten (1962; Little Brother and the Lad) only has a father – her mother has gone to England with a new husband. Aurora’s mother is an attorney, while her father stays at home working on his doctoral thesis. Guro’s mother is a caretaker – her father is dead. In the final series, the main character has the symbolic name of Kaos. He is an only child in a world of other only children and busy parents. Kaos’ mother becomes a weekly commuter in order to earn her degree, and his best friend Bjørnar has a father who is a weekly commuter as well. Bjørnar himself has spina bifida and is bound to a wheelchair, but gets by anyway – by virtue of his own resources and with the help of others.

Anne-Cath. Vestly’s entire body of work is populated by a number of special characters so that “normal” becomes deviant. And the grandmother is ever-present in the various series, linking the characters and the books. In this way, Vestly possessed a firm grasp of the different issues of the time, while at the same time communicating a strong faith in the inherent possibilities of children and adults, if only they are considerate of each other and leave room for being different.

Uncertainty and the need for anchoring are given a strong voice in the works of Anne-Cath. Vestly through children’s relationships to the houses they live in. Each child she depicts has a close yet distant relationship to the space around them, to the setting of their daily lives, regardless of whether it is a newly-built house, an old cabin in the woods, a flat in an urban building block, or a concrete tower block in the suburbs.

Anne Birgitte Rønning

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd

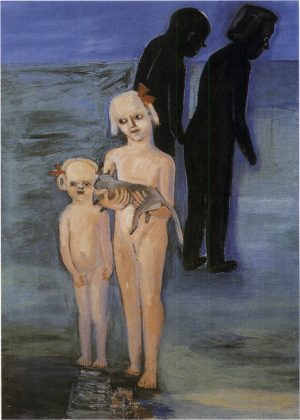

The Child in the Eye of the Storm

Maria Gripe (born 1923) made her debut in the 1950s when the child, both in literature and society at large, was viewed from an outside perspective. In her first books, a living cuddly toy is made to speak for the child as a sort of surrogate child with a worm’s eye view of things, but beginning with Josefin (1961; Eng. tr. Josephine), Maria Gripe changed her perspective. Here the world, not to say the universe, is seen strictly through Josephine’s eyes. Outside is the adult world; apparently incomprehensible, irrational, and above all on the other side of an abyss. This insurmountable abyss and the total anarchy of the adult world (seen from the point of view of the child) is the theme that Maria Gripe never abandoned. In book after book she depicts the child stuck in the eye of the storm, without the ability to create a communicational link between itself and the adults; exposed to the incomprehensible laws of the adult world, but with a preferential right to its own interpretation of these laws and a marvellous vitality. Maria Gripe’s children are often survivors, children who should be emotionally crippled, but who have survived against all odds.

The Invisible Directors

A recurring theme throughout Maria Gripe’s books is the elusive and self-absorbed mothers and the missing, missed, and doubly lost fathers. The divide between parents and children seems to originate not in a lack of love – quite the opposite, in fact – but in a lack of insight, and in some cases a lack of moderation.

Mothers smother the relationship with their children in an excess of love just as often as they ruin it through self-absorption and unconscious cruelty. With notable frequency mothers abandon their children, usually with the noblest of motives, in the work of Maria Gripe. Lydia de Leto, the mother of the twins and Caroline in Maria Gripe’s books about the shadow, Skuggan över stenbänken (1982; The Shadow upon the Stone Bench), …och de vita skuggorna i skogen (1984; … and the White Shadows in the Forest), Skuggornas barn (1986; Children of the Shadows), and Skugggömman (1988; Shadow Hideaway) is unique in that she twice pretends to die from her children, first in the role of Lydia/Ophelia and then in the role of Ida. Berta’s mother in the same books betrays her children due to her helplessness.

The fathers are their profession, career soldier like the father of the twins, teacher and above all scholar as in the case of Caroline and Berta’s father, or parson like Josephine’s father. Their professional roles distort their humanity and make them inaccessible. Like shadows falling on the children these fathers control the lives of their children without making themselves visible to the children, and the foremost feeling they arouse is one of loss and absence. The children’s thoughts often revolve around the father figure, but in his absence images and shadows are built that grow more real than the human being.

Negligent mothers and absent fathers are also found in Hugo och Josefin (1962; Eng. tr. Hugo and Josephine), in Pappa Pellerins dotter (1963; Eng. tr. Pappa Pellerin’s Daughter), and in the books about Elvis: Elvis Karlsson (1972; Eng. tr. Elvis and His Secret), ELVIS! ELVIS! (1973; Eng. tr. Elvis and His Friends), Den “riktiga” Elvis (1976; The ’Real’ Elvis), Att vara Elvis (1977; Being Elvis), and Bara Elvis (1979; Only Elvis).

In Tre trappor upp med hiss (1991; Three Floors Up with Lift), Maria Gripe shows the upper-middle-class family with the tyrant/managing director at the top of the pyramid with Lotten and her Mother (and the disappeared father) for contrast. The house takes on the characteristics of a psychological landscape. The excursions Lotten makes at night through a moonlit dwelling become an exploration of a strange world, with rooms as large as continents and corridors like dangerous passages to the unknown. That these excursions take place in moonlight demonstrates how the father-house at night can be invaded by emotions and therefore may be explored, even by one who rightly does not belong there. Since sight is not to be relied on by moonlight, Lotten has to use her other senses, such as her sense of smell, to get an impression of the various continents, such as the study (tobacco), or the lady’s room (floral scent), precisely as an explorer approaches a strange coast and feels new scents meet him while still at sea.

The Lie as a Defence

In the wake of powerlessness follows lying. Elvis’ mother in the books about Elvis (1972–1979), this horrid yet pitiful woman whom “no mother rightly can abjure her affinity with” is in all aspects a brilliant portrait of a grown-up completely caught up in patterns and behaviour, the mechanisms of which she is incapable of understanding or even seeing. Against her complete and self-contradictory foolishness, Elvis has only two options for defence. He can either keep silent or lie, but since remaining silent is considered a kind of reverse lie the consequences are the same.

The lie is the price of adaptation, the defence grown-ups surround themselves with not to be broken down by the falseness of existence. It therefore seems to the child that the adults are allowed to lie while the child does not have that right. Maria Gripe’s children entangle themselves in spider-webs of lies and untruths – they have discovered that adults would rather believe lies than the truth.

“Adults are complicated. Children who lie betray themselves almost right away, they are not that polished. But adults believe in their lies. Or in the right to lie. Children never have that right. Their lies are just shameful. But the lies of adults are always defensible. Adults only lie out of concern, consideration, or wisdom, their lies are always white. At least that’s what they want children to believe.”

Agnes Cecilia – en sällsam historia (1981; Eng. tr. Agnes Cecilia)

Carolin Jacobsson, the Shadow tetralogy’s secretive protagonist, is a young woman who appears to be in control of her own destiny, and who seems to know how life should be handled. The driving force in her behaviour is the search for truth about her origin, which is the existential question: who am I really? Her first appearance, in Skuggan över stenbänken, is an entrance in a play, and this key scene foreshadows much of what will carry the narrative through the books.

Carolin’s unique personality makes it impossible for her to enter the house of the narrative through its real doors. She will not be tamed to obedience, silence, and compliance: she is an impulsive, emotionally-driven person who lives according to the motto that the end justifies the means. She wants to be the director; she changes the stage directions, places herself on a black square when convention prescribes a white, and makes entrances and exits entirely according to her own head. By not being who she pretends to be, by sliding in and out of various roles, she can disguise herself to her fellow actors. She washes out the truth through her tomfoolery.

Carolin in Maria Gripe’s Shadow tetralogy wants to make herself visible in the darkness of female convention, and therefore acts as a boy. She does it so convincingly that the only one to reveal her is an old lady who has chosen to go blind to be rid of the limitations of the sense of sight. Gender thus becomes a disguise that hides the inner core of the human being, a disguise that blinds and enslaves.

A character’s name is often the most significant symbol of identity for Maria Gripe. In the books about Elvis Karlsson, Maria Gripe has made the name into a careful metaphor for isolation. Elvis Karlsson is not Den “riktiga” Elvis (1976; The ’Real’ Elvis). In the Shadow tetralogy this reverse naming magic is prominent. Clara de Leto, the dominant maternal grandmother from Carolin and the twins’ past, is herself anything but clear (klara means ’clear’ in Swedish). Nor are you ever supposed to forget her (compare ’lete’, the Greek for oblivion), and Carolin in Skugggömman searches (’leta’ in Swedish) intensely for traits of the grandmother’s personality within her own.

Irrespective of genre, all of Maria Gripe’s books are about family and the child’s position within it. Ever since Josefin first appeared in 1961, caught in the eye of the storm, Maria Gripe has consistently, if in more complex ways, explored the same theme again and again. Not a single parent in her works does the right thing. All contribute to stunting and suffocating initiative, vitality, and spontaneity. Hope is only found within the child.

Gabriella Åhmansson

Translated by Marthe Seiden

The Modern Girl’s Book

In the postscript to the semi-documentary young adult book Stærk nok? (1979; Strong Enough?), the author and social worker Tine Bryld (1939-2011) declared the death of the girl’s book – this “strange pink rubbish”. The girl’s book – understood as trivial gender polarising book series – was already in decline in the mid-1960s. The Danish Puk and Susy series, both written by men under female pseudonyms, ended in 1964. A few series of girl’s books appeared during the 1960s, although they never achieved the same popularity as Puk and Susy.

However, the pioneering contemporary realistic young adult book The Outsiders (1967), written by the eighteen-year-old American writer Susan Hinton, heralded new ways of depicting the experiences of young people, and had an impact in Denmark through the social-realist young adult fiction of the 1970s. In contrast to the older, often moralising literature, the modern young adult book breaks down both systems and taboos. No theme is off limits, and traditional gender roles, relationships to authorities, and social structures are criticised more and more openly. The points of view and sympathies of the new generation of writers are with the books’ young, often maladjusted and rebellious main characters, who are in discord with themselves and with the adult world around them.

Tine Bryld’s own novels for young adults, especially the trilogy about the girl called Liv (Danish for life), Pige Liv (1982; Liv a Girl), Befri dit liv (1983; Free Your Life), Liv og Alexander (1984; Liv and Alexander), are good examples of the period’s new contemporary-realist (series of) girl’s novels which, like the books for young women by Hanne-Vibeke Holst, Dortea Birkedal Andersen, Lotte Inuk, and Marianne Koester and Kjeld Koplev, deal with typical experiences and conflicts of the girl cultures of the 1980s.

Tine Bryld’s trilogy depicts Liv’s development from girl to woman. It starts with the good old-fashioned meeting with the great, all-consuming love, but ends with Liv saying good-bye to her beloved, once so attractive, but now so dependent Alexander. The schoolgirl the reader meets in the first book has by the end of the third book become an independent young woman on her way out into the world, matured by her meeting with both love and the urban squatter milieu. Like an increasing number of female main characters in the young adult fiction of the 1980s and 1990s, Liv flies from a boyfriend and from being a couple to conquering the world and realising herself.

Confrontations between daughters and mothers is a recurring theme in the girl and young adult novels by Tine Bryld and a number of other authors of the same period. For instance, a fierce row between mother and daughter is a key scene in her novel Talkshow (1990). The young Nadia accuses her mother of not loving her: “If you knew how many times I’ve cried, longing for you, hating you. Well, you can be rid of me […] Remember that I’m there! Remember that when you tell those poor mothers that they have a right to a life. That they don’t have to let themselves be bullied by horrible children who force them to be at their beck and call all hours of the day with clean clothes and food, and to drive them around. Tell them it is harmful to be caring, that parental love is an expression of the deepest neurosis […] Tell them that they should get therapy to talk about all the feelings they don’t have!”

While Tine Bryld’s main character is on her way out into the world, Louise in Hanne-Vibeke Holst’s young adult trilogy Til sommer (1985; This Summer), Nattens kys (1986; Kisses in the Night), and Hjertets renhed (1990; Pure of Heart) ends up back in her home town revisiting the boyfriend of her youth, Anders. Only for a brief period, however. Louise is on holiday from a stressful career abroad and has returned to the quiet of home to “think things through”. Even though Louise, during the course of the trilogy, achieves reasonable clarity about the fundamental questions that repeatedly crop up in the young adult novels of the 1980s and 1990s – Who am I? What do I want? Who and what should I choose? – she still takes a step back from her busy career to ask new questions about what she left behind and what her best friend Stine has conquered instead: Anders, baby, and the little house in the country.

Erotic love is the basis for the development of the young main character’s identity in Hanne-Vibeke Holst’s trilogy. Louise’s dilemma is a classic case of the woman divided between two diametrically opposed types of men: the safe Anders and the seductively “dangerous” Jesper, whom Louise finally chooses in the end. Between the opposite ends of the masculine spectrum is a brief encounter with a third male character, Peter, a saxophone-playing street performer and poetic artist of life who suddenly and tragically dies the day after he and Louise fall passionately in love. Peter is a utopian and glorified mediation character – bright and expressive in his gestures and movements, with a sensual mouth full of the night’s turbulent kisses. He disappears from the plot level of the story, but remains as a symbol of the unattainable target of Louise’s conflicting longings.

Lost love and separation are recurring motifs in a number of books for young adults of the period. This goes for girls’ relationships with their boyfriends, girlfriends, and parents. The development process from child to adult seems invariably associated with the pain of losing someone or something. Love and death are closely connected, especially in the works of Lotte Inuk, in which they sometimes enter into a form of romantic alliance. Many restless and abused children and young people in Lotte Inuk’s books are driven by a common magnetic longing for the great, all-consuming, and sometimes lethal love.

In 1980, at the young age of fifteen, Lotte Inuk won a short story contest for young people, and a couple of years later she had her debut with the novels Maria Mia and Mona Måneskinsdatter (Mona Moonlight Daughter), both in 1982. Her writing introduces a different poetic imagery and linguistically sensual literary style to Danish literature for young adults. Forms of expression from the electronic visual media have left their mark on Lotte Inuk’s novels, and on many other books from the 1980s and 90s that embody the new trends in form. In addition to the use of visualisation, Lotte Inuk mixes realism with elements of fantasy, fairy tale, and mysticism, using romantic stylistic figures and metafictive narrative techniques that make her books radically different from the genre of social realism that dominated Danish young adult and adult literature in the 1970s.

Despite the unique writing style, her work is both aesthetically and spiritually allied with the lyricism of the 80s, and heralds the postmodern, genre-hybrid, and intersexual styles that characterise the avant-garde school of Danish literature for young adults on the threshold of the 1990s. Common to the avant-garde school of young adult fiction, and to such different authors as Lotte Inuk, Bent Haller, and Louis Jensen, is the metafictive, labyrinthian nature and the openness to interpretation of the narrative form in their texts, which makes a break from the solid foundation of pedagogical principles that are as old as juvenile literature itself.

One of the most innovative and boundary-crossing characters in Lotte Inuk’s body of work is the female Don Juan – Gina/Regina. She is an erotic force who entices both sexes in her never-ending, restless search for true love. In Gina, je t’aime (1993), we meet Gina in the critical years of puberty. In flashbacks through her friend Lucy, the novel gives hints and fragments of Lucy’s close and complicated love affair with the Portuguese girl Gina, whose tarnished past and exposed life in Paris result in a fascinating combination of childlike innocence and adult experience. Gina is only eleven years old when she and Lucy meet for the first time, but she is much more experienced than her two-year-older friend. To an extreme degree, Gina represents the duality in the life of a modern young adult, spanning from childish play to adult wisdom. Gina is the adult child who sees through life’s rules and secrets, even before she has experienced them in her own body. Ever-sensitive, she reads the signals, looks, and touches, and learns to master the masquerade and exploit the pubescent flip-flopping between girl and woman.

The girl’s bedroom provides an important framework for the socialisation of the modern girl and for friendships. The bedroom is the young girl’s sanctuary, free from the adult world outside, as well as a kind of practice room in which the many women’s roles are tried out. The girl’s bedroom in Lotte Inuk’s Gina, je t’aime, (1993) is called “Nirvana” in reference to both the seventh heaven and another of the author’s young adult books, Villa Nirvana (1984): “In here, behind the shut light-blue door, it is safe and comfortable and good, like in a cave far away from the rest of the world, insulated with two layers of posters and cuttings covering the walls: Regina’s half of the cave is decorated with a few cuttings about Barbie as well as posters of The Cure and of Bruce Springsteen […]”

Many of the restless travellers and love-starved young people in Lotte Inuk’s universe are bisexual. They experiment with the multitude of erotic modes of expression just as the author unvaryingly experiments with the text. The limits and meaning of gender are constantly shifting. Through cross-cutting points of view and chiasmic structures, female and male narrators slide in and out of each other to either melt androgynously together or perish in indefinition.

Other writers of fiction for young adults from the 1980s and 90s approach the formation of gender identity through the fantasy genre’s archetypal and mythological scenarios. With references to Astrid Lindgren’s Brødrene Løvehjerte (1973; Eng. tr. The Brothers Lionheart) and Mio, min Mio (1954; Mio, my Mio; Eng. tr. Mio, My Son), Anne Lilmoes (born 1945) depicts in Du, min Jonathan (1990; Jonathan my Dear) a young girl’s journey of discovery through the fairy tale world of the subconscious – a journey that brings Kimmie from mental collapse to erotic breakthrough, from the child’s sharply black-and-white view of the world to a more nuanced and colourful world view.

The fantasy genre’s fantastic and symbolic landscapes are apt, both as psychological spaces and as spaces for the so-called “grand narratives” which the postmodern breakdown of meaning has made it more difficult and perhaps more important than ever before to tell. Grand narratives about creation, chaos, war, and love form the basis for Anne Lilmoes’ epic Yaxhiri series (started in 1993) and Josefine Ottesen’s (born 1956) Eventyret om fjeren og rosen (1986; The Tale of the Feather and the Rose). And it is from this platform of the grand narrative that male and female archetypes re-enact the discord, disputes, separation, and reunification of the sexes.

Gerd Rindel’s works are central to Danish children’s literature, and she wrote a large number of historical novels in the 1980s, when many Danish writers returned to the fantasy genre as well as the historical genre as a contrast to the contemporary realism of the 1970s. A number of historical novels were published during that decade, many of which were set in the occupation years during World War II. In addition to Gerd Rindel’s Tusmørkebørn (1984; Twilight Children) and Hvor roser står i flor (1986; Where Roses Bloom), Hjørdis Varmer wrote an occupation-years trilogy beginning with Det forår da far gik under jorden (1980; The Spring When Father Went Underground). Iris Garnov wrote a series about the childhood of the young Yrsa in Denmark of the 1940s and 50s, beginning with Nogen gange skinnede solen (1980; Sometimes There Was Sunshine). Even the young Cæcilie Lassen contributed to the genre with the novel Simone (1987).

In addition to her historical novels, books for adults, and picture books, Gerd Rindel has written the magical-realist, young adult work Et spor i Rusland (1991; A Trail in Russia), which couples a modern story about a young woman’s identity formation with the history of her family and of Russia. At the start of the novel, the young main character, Jelena the Third, faces a dilemma that she shares with many of her contemporary literary characters. Like the young king in Josefine Ottesen’s Eventyret om fjeren og rosen,she has no history or memory. In the search for her own identity, Jelena looks back to both her family roots and the history of her native country. This becomes a point of departure for a journey from Denmark to Russia, and from the atmosphere of upheaval of the 1990s back through one hundred years of Russian history: from the days of the Tsar through the Communist revolution to Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika.

Et spor i Rusland does what the Norwegian author and historian of ideas Jostein Gaarder also seeks to do with his philosophical books for young adults: anchors the disconnected individual in a larger historical perspective by re-establishing meaning in postmodern society’s collapse of meaning.

Before the young Jelena leaves Russia, she receives an old family heirloom: a silver egg formed like a Russian Babushka doll. Symbolically, the silver egg represents Jelena’s newly acquired insight into the history of her family: she is an egg within an egg within a long generational line of silver eggs. Jelena’s new understanding of her past gives her courage and ideas for the future.

Jelena decides to become a pilot – an ambition she shares with the young Sally, the main character in Dortea Birkedal Andersen’s raw, satirical, and linguistically sharp story for young adults, Sallys Bizniz (1989; Sally’s Bizniz). Sally dreams of flying away from her hopeless home in the concrete slums full of “damned kids”, “wogs”, and unemployed football fanatics, and where every day people give up the struggle and jump from the tower block rooftops of Hyrdindeparken (Shepherdess Park). Suicide pilot – no thanks. Sally is more ambitious than that, and even though “women have to be royalty or even worse” to become fighter pilots, she can at least be a “seaplane pilot” and put out forest fires in Canada.

Sallys Bizniz is both similar to and very different from the young adult books of the 1970s. The descriptions of the local environment and the uncompromising pessimism are the same, but its rough and reckless humour, its grotesque, almost surreal exaggeration, differ from the mainstream of social-realism.The humour, which is something of a scarcity in the young adult fiction of the period, combined with the novel’s loud, energetic language ripe with the jargon of youth, gives it a qualitative boost that had an impact on the more innovative works of Danish young adult fiction in the 1990s. It is yet another example of how past pedagogical frameworks have been torn down to make way for new genres and narrative styles that both aesthetically and thematically explore the ruptures in postmodern culture.

In many of the Danish young adult books of the 80s and 90s, the young girls leave home with their rucksacks and a restlessness pulsing through their veins, or they fly out into the great world. Sally in Dortea Birkedal Andersen’s novel dreams of becoming a pilot, of sitting in the cockpit herself: “They have been running an ad in the newspaper recently: ‘Complete commercial pilot course in Houston, Texas, USA for just 7,355 US$’. You just have to be 18. And she already has the first 27 US$ converted at the best exchange rate. That means she just has to wait four years and get her hands on another 7,338 US$. Then she’ll be the happiest girl alive.”

Anne Mørch-Hansen

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd