A feeling that time is just passing by, and a longing for freedom, love, and a language that can contain life’s and the ego’s many sparkling facets makes itself felt in many texts by debut authors of the 90s, such as in the poetry of Katrine Marie Guldager (born 1966). “Mosaik” (Mosaic) from her debut collection, Dagene skifter hænder (1994; The Days Change Hands), expresses the desire to find a voice, a poem:

I am tired

and of the day’s final hour

I desire a poem

spun from a thousand threads,

habitable and porous.

I wish for poems

like an incomplete glass mosaic

that shines in blue nuances across the Russian steppes; the refinement

of detail like an answer and not.

I wish for a voice

which in the final light of day

weaves together:

Around my ice-cold hand

and the familiar smell of sweat and perfume.

The poem should be able to reflect the self, be habitable yet incomplete, imperfect. The poem should capture and show the shifts in sense and mood that the ego constantly experiences. The realisation that life and humanity are in movement in time and are changing states is central to Dagene skifter hænder and neither the poem nor the poetic speaker strives to discover a permanent meaning, much less coherence. The poetry of the 1990s does not lament the loss of meaning or identity, or make the body an ultimate point of reference, but seeks glimpses and identity in movements and by changing direction: “[…] Under your star I am always on the way / towards something else: / Behind me I drag a trail of derailed carriages / and days tear themselves free”.

The linguistic tone and themes of her debut collection are rediscovered in Katrine Marie Guldager’s prose poems in Styrt (1995; Eng. tr. Crash), such as in the poem “Vindue” (Window):

“I only recognise half of what should be my life: The weeks cut into my skin like a net I only briefly can see through. I get up, and stumble out in the streets in raving intoxication, fall over a gull cry and call it mine. I throw out my arms and stop caring: my memory is like windows in the spring, which flake off and off, that I remember, like the rotting wood that slowly falls apart.”

Within poetry it is possible to point out various literary paths and positions. For instance, a suggestive, carved symbolism appears in the work of Lene Henningsen and Annemette Kure Andersen, while Kirsten Hammann, Lone Munksgaard Nielsen, and Camilla Deleuran embody a humorous, absurd modernism. To this can be added the lyrical descriptions of daily life in the works of Naja Marie Aidt and Katrine Marie Guldager. Reminiscence, childhood, love, gender, and the body are central motifs in both poetry and prose.

The literature of the 1990s primarily perceives life and the formation of meaning as transformation or movement. And it is in a movement around a female character that the ego is staged, with its entire baggage of pain, loneliness, longing, self-destruction, irony, and humour. The ego is invented, explored, thinks, or is present as a textual energy in the narrative or poem.

One sign of the striking placement of women in young literature was the Danish daily Politiken’s comprehensive article series “Litteraturen ind i 1990’erne” (Literature into the 1990s) from 1994, in which all the new authors profiled were women: Solvej Balle, Kirsten Hammann, and Merete Pryds Helle.

The many young writers who made their debuts in the 1990s have become the object of much attention, as is for instance the case with Merete Pryds Helle’s dual-tracked philosophical novel Vandpest, Solvej Balle’s clear-cut stories in Ifølge loven (1993; Eng. tr. According to the Law), and Katrine Marie Guldager’s everyday poems in Styrt (1995; Eng. tr. Crash). In the new prose, women writers appear to be in the majority, and many of the works have quickly found their way to larger audiences, such as the debut novels by Christina Hesselholdt and Kirsten Hammann, which are available in paperback, as are poetry collections by Naja Marie Aidt and Karen Marie Edelfeldt.

The Danish Academy’s award for debut authors, the biennial Klaus Rifbjerg Debut Prize, has been awarded to women writers since 1990: Karen Marie Edelfeldt (1990), Lene Henningsen (1992), and Kirsten Hammann (1994).

“Spun from a thousand threads …”

The title of Lene Henningsen’s (born 1967) Jeg siger dig (1991; I Say You) can be interpreted as an address, a confidence, partly as the evocation of a meeting in which I say: you. However, the substance is not only the meeting between the poetic speaker and a male ‘you’. The desire to explore and listen to other layers of the self (“to say you of the self”), and the longing to identify something unspeakable in the meeting between body and soul also gets the speaker started “searching in words for space”. It is the musicality of the voice and the indefinite, expressive images that are important in this search. The collection’s division into three parts – “Towards space”, “Late escape”, and “In your night now” – hints at the poems’ outward and forward movement towards something: towards the meeting, abandonment, and transformation. Lene Henningsen is interested in differences and distance in and between people. And when the speaker asks “And how far can we get?”, only provisional answers and places are given in the whirling dream language of the poems.

After the poetry collections Jeg siger dig, (1991; I Say You), Sabbat, (1992; Sabbath), and Solsmykket, (1993; The Sun Jewel), Lene Henningsen continues her efforts to unite dream, poetry, and life in the poetic fragment En drøm mærket dag (1994; A Dream Labelled Day), with the subtitle “Telegrammer om digt/liv” (Telegrams on Poetry/Life). In telegram style, the author consistently cuts her way to the essential aesthetic and existential question:

Dream, go along with language

disappear.

The damned important I-land

disappears. Only a thin

thread connects to

what was.

Sent out between familiar

and foreign,

supporting and non-supporting,

truth

and lie in language/life.

Out on the line, foreign. Can

not

expect it, but meet: what

can be

given, a ritual. Cleansing.

Annemette Kure Andersen (born 1962) made her debut in the same year as Lene Henningsen, with the collection of finely honed verse Dicentra spectabilis. The title is the Latin name for the Old-fashioned Bleeding-heart flower, and the author references the nature’s flora and colours both here and in the subsequent collection Espalier (1993; Trellis). “Ravenna” is the name of a poem in Dicentra spectabilis: “Burnt colours / of fragments / gathered into / a picture”. In addition to referring to the famous mosaics of the Italian city, the poem also hints at Annemette Kure Andersen’s attempt to reduce the linguistic material as much as possible and arrange it in new patterns and images in short, suggestive stanzas, for instance here in the poem “I brand” (On Fire) (Dicentra Spectabilis):

The hawthorn

blossoms

The longest day of the year

The transformation

As she grasps at him. She grasps.

Before she is able to turn him around. Turn him.

He turns around. He turns.

He turns around and receives the grasp.

I held my own hand as I ran up

the hill. I stretched my face forward and

met a stranger’s lips about to kiss my kiss

Iben Claces: Tilbage bliver (1994; What Remains).

Impressions of nature, landscapes, and nuances of colour are incorporated into these minimalist poetry mobiles. Annemette Kure Andersen especially seeks out the almost invisible processes under which atmospheres and material alter their state and perhaps disappear entirely in the end. Landscapes, people, and emotions crack, are crushed, or overwinter. Time plays its part in the transformations, and its presence becomes very strong in the poems whose inner circle of silence leaves trails of a once-existing longing or fertile state.

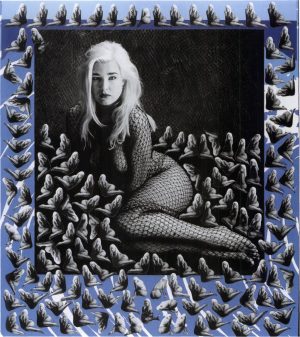

Camilla Deleuran (born 1971) and Iben Claces (born 1974) made their debuts, like Katrine Marie Guldager, in 1994 with the poetry collections Glashud (Glass Skin) and Tilbage bliver (What Remains) respectively. In Camilla Deleuran’s Glashud, love’s many faces and conflicts are exposed in an insistent tone that stands as a contrast to the vulnerability and frailty depicted in the poems. The book’s cover, featuring the exposed muscles and tendons of a cranium, illustrates the process of laying bare love’s “invisible” emotional threads. The “glass skin” metaphor used in several of the poems refers to the poetic speaker’s experience of the frailty of the body and of love – the idea of being transparent and open to another’s penetration: “At that moment […] the fear hits you like broken eggs, you think: ‘I am as easy to poke a hand through as glass’”. But the glass can be shattered into sharp shards, and love contains the pain: “He bends over and gathers […] shards of glass up, collects them, making little cuts in the paleness of his palms”. In the short and often mournful poems in Tilbage bliver, Iben Claces stresses the impossibility of reaching the other in love. The collection comprises four poetic cycles entitled “trappen: fald” (the stair: fall), “parken: sammenfald” (the park: coincidence), “natten: forskydning” (the night: displacement), and “mødet: sammenfald” (the meeting: coincidence), which show the elements and development of the poetic speaker’s experience of self and of the surrounding world. The stair is the connecting link to the world outside the childhood home, to the playmates, and to the exertions in the park. However, “the stair collapses” – the fall and the loss of innocence is unavoidable – and “What remains / a set of hands / a mouth and a cry”.

“When you describe peculiar characters – they are the ultimate consequences of certain things that we all carry around within us, they are just extremes – then you may, through them and their sick universe, grasp that it is important that you also go wild in your life, that you also make room for yourself in your existence instead of throwing yourself into the giant security […].”

Interview with Naja Marie Aidt in the Danish literary journal Ildfisken (7/1993; edited by Carsten René Nielsen).

“Each her own pain …”

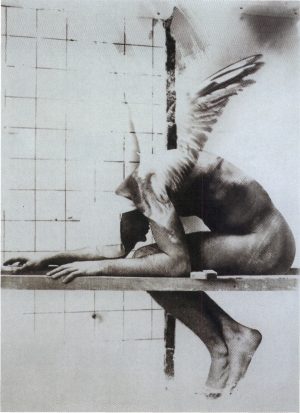

Lone Munksgaard Nielsen (born 1968) experiments with various genres in her books Afvikling. Opstart – Afstemning – Forløb (1993; Phasing out. Start-up – Reconciliation – Process) and Frasagn – Rygvis & Den længste sommer (1994; Legend – Back to Back & The Longest Summer). Poetry, prose, and drama are mixed in a hybrid that stages several characters or links several voices into one and the same character. The vulnerable relationship between body and psyche, between self and world, between the present and childhood memories, and between lovers is thematised in brutal, morbid, and expressive imagery in which dreams, traumatic experiences, and the frailty of the psyche are illustrated. In Frasagn’s poetic suites, “Rygvis I & II”, the fulcrum of the poems is the distance and deprivation in the relationship between him and her. In the surreal sequences “Hun drømmer, at hun langsomt klipper vingerne” (She dreams that she slowly clips her wings) and “Han drømmer, at han river sin rygsøjle ud” (He dreams that he rips out his spinal cord), love is visualised as amputation and destruction, and the question is asked: “Do you believe you can be infected by love?”

In the insistent tone of the poems in Mellem tænderne (1992; Between the Teeth), Kirsten Hammann (born 1965) establishes dramatic and expressive images of being foreign to oneself, to one’s body, and to the surrounding world. In several pieces, the poet gives the body a life of its own while at the same time considering it part of the self. Mellem tænderne is characterised by its angry, desperate, vulnerable, and sneering humorous rhetoric: “I am so tired of my body / I must teach it / and command it / and speak in harsh words […] If we have been on a walk in the park / it remains sitting on the bench / so I have to go back and fetch it / It is in every way childish and unreasonable / Soon I can no longer have anything to do with it”.

In Naja Marie Aidt’s (born 1963) poetic trilogy comprising Så længe jeg er ung (1991; As Long as I’m Young), Et vanskeligt møde (1992; A Difficult Meeting), and Det tredje landskab (1994; The Third Landscape) the focus is openly and directly, but more quietly, aimed at the immediate surroundings – the close relationships in life. The poems are about family life and love, depression and irresolution, the fear of being alone, of a life of conformity, and of growing old. However, they also depict moments of closeness and happiness: “Still / summer came. / You remember me based on / how many summers have passed. / We each sit in separate chairs / but form a bridge / with our hands. // […] / Each chair contains / its own pain / you say it is a good thing / we don’t have a bench. / We form a bridge / from our separate nights / with hands that glow / of old / and new / kisses”, from “Endnu en sommer” (Yet Another Summer) in Et vanskeligt møde. Love disappears, but can suddenly show up again as new caresses, and in this way Naja Marie Aidt’s poetry shows several levels of movement between standing in the midst of the pain of disillusionment and the noble re-enchantment and return of life.

“Luckily the crib faced the window, and in the four years Jasmin spent growing out of it, her eyes became the colour of fog and overcast days, sunshine and drifting clouds. When it rained, she knew the relief of the drops, a chorus of voices flowed through the window, became missed hands and a quiet whisper”.

Merete Pryds Helle: “Skabet” (The Cabinet), Imod en anden ro (1990; Towards a Different Calm).

Prose Pieces – With the Voice as a Weapon

A brutal and at times frightening tone characterises Marina Cecilie Roné’s (born 1967) monologue Skrifte til min elskede (1993; Confessions to My Beloved), in which the female first-person narrator, like a modern day Scheherazade from The Arabian Nights, in a sharp and sarcastic tone tells her life’s confessions to the silent ones closest to her – that is, men, lovers, and children. Conscious of the fact that her words will get her burnt at the stake as a mad witch, the elderly woman sets her voice free and strips bare the fundamental, interhuman relationships: “my voice is my only weapon. Are goodness, love, and motherly affection just a show disguising a fundamental egoism? – The infection is in my soul. Everything I have done was to relieve its constantly throbbing pulse. If I gave a kiss, it was to get one back or to hear you ask for more.” The devouring and biting insistence on penetrating deep beneath all lies and escaping the illusions takes on an immediate and malevolent nature, but is also a self-defence mechanism and a longing for continued dialogue: “It is not until I have been stripped naked and forced through every single one of my humiliations, vices, and lies that I am ready to love.”

Naja Marie Aidt, with the collections of short stories Vandmærket (1993; Watermark) and Tilgang (1995; Approach), and Merete Pryds Helle (born 1965), with Imod en anden ro (1990; Towards a Different Calm), each present in their own way a biting portrait of loneliness, isolation, and death. In the fairy tale-like and poetic short stories, grotesque scenes are played out, such as a scene from Merete Pryds Helle’s story “Skabet” (The Cabinet) in which a mother keeps her child locked away for years, or the story of a socially withdrawn and sociophobic woman who caresses herself and poses in front of the mirror, in Naja Marie Aidt’s “En kærlighedshistorie” (A Love Story). In poetry as well as in prose, the woman is the incarnation of the lonely and vulnerable person, and this demonic power cannot be lifted through an outer liberation. Beneath the psychological concentration and the sharp language lies a need for continued dialogue about and with the conflict areas of the body and the psyche.

The Endless Wanderings

Telling stories while at the same time making room for artistic experimentation is one of the aims of Merete Pryds Helle’s work, and especially of her novel Vandpest (1993; Water Thyme). In the collection of short stories Imod en anden ro, various types of narratives are tested, and in the novel Bogen (1990; The Book) a complex crime plot plays out in which the author, the text, the characters, and the reader are all involved and made accomplices in a mysterious death.

Solvej Balle’s condensed prose style and poetic, philosophical reflections in Ifølge loven (1993; Eng. tr. According to the Law) were anticipated in her debut novel Lyrefugl (1986; Lyre Bird) and in her short prose work & (1990). Lyrefugl is a Robinsonade about the woman Freia who, after ending up on a deserted island following a plane crash, attempts to build up a civilisation. But over time, Freia begins to doubt whether the knowledge and the sense of order that she and the entire Western world possesses actually makes sense:

“If there is a truth, then why hasn’t anyone come up with it ages ago […].”

“First you write a novel. Then some short texts and now four stories which are, however, connected in several ways. There appears to be an unwillingness in your generation to write great novels”

[…] “I found it necessary myself to search deep down in the skeleton of the narrative, to put the narrative itself under a microscope. […] If you feel – and maybe that is what I do and other [authors] do – that a specific form cannot contain what it is important to write, then there is no reason to use that form [i.e. the classic story].”

Interview of Solvej Balle by Marianne Juhl in the Danish weekly Weekendavisen (1-7 October 1993).

Vandpest’s plot, composition, and psychological effect are nothing less than frightening. The story about the aggressive plant, water thyme, forms a psychological and plot-related backdrop to the main character Beatrice’s journey into a nature that has run amok.

As a parallel to Dante’s Inferno in The Divine Comedy from the 1300s, Beatrice’s and Malcolm’s balloon adventure ends in a frightening landscape where they meet the married couple Agnes and Mikael with their twelve-year-old daughter Kate. After having attempted to smuggle heroin in the body of Kate’s twin sister, the family has ended in an ecological nightmare, a landscape whose perpetual pendulations between destruction and genesis becomes symbolic of the couple’s murderous deed.

However, it is impossible for Beatrice, her surroundings, or the text to be fixed in an ultimate ending. Vandpest is written on two levels – a narrative text and a text comprising older scientific descriptions from encyclopaedias and the like – which serves to emphasise the multiple meanings and unstable nature of the prose.

Solvej Balle (born 1962) also works with quotations and commentary in Ifølge loven. These “four accounts of mankind” each have a section of an Act as motto and framework. Stylistically, Ifølge loven is almost clinical prose, which in its lack of pathos and emotional outbursts appears closely related to the investigative projects carried out by the characters in the narratives. The four main characters in the stories are searching for truths or laws that can alleviate their experience of having lost meaning and orientation. The scientist Nicholas S. is searching for the molecule in the brain that makes it possible for humans to keep themselves upright and in movement. Tanja L. is preoccupied with finding and getting to know pain, and travels across half of Europe in her search. The mathematician René G. attempts to escape society’s network of meaning out of a desire to become nobody. And finally, the artist Alette V. commits suicide to become “equal” to the harmonious objects she views as ideal.

The characters’ explorations end in a kind of existential dead end. The impulse for self-realisation sends these modern urban nomads on journeys to achieve insight into people and themselves, but the path takes on the form of a labyrinth of isolation and insecurity. Even death no longer represents the finality that can put life into perspective or be a “way out”. Ifølge loven’s sharp language retains the characters’ odd sense of happiness about their own imprisonment, pain, and disintegration.

“Two streets further away, a man has finally hung the picture on the wall. […] The man straightens the picture and gets his rifle. A hole is put in the wall. It is otherwise made of a hard material. In the neighbouring flat, a young man stands with a pistol aimed at his temple. He does not believe he actually fired it.”

(Helle Helle: Eksempel på liv (1993; Example of Life).