Female poets of the early twentieth century discreetly described sexual experiences in terms of grass that smoulders or is flattened like a mat beneath the lovers. Eventually, the euphemisms grew unnecessary. In 1927, Ingeborg Björklund (1897-1974) wrote brazenly about a lover lying in her bed. She knows he will be gone at dawn, but “still intoxicating / I feel the heat of his round, muscular shoulders” – “Till Diana” (To Diana) in Den spända strängen (1927; The Taut String).

Maj Hirdman (1888-1976) touched upon the most private of matters in 1909 with a poem penned for her own consumption about her longing for children. Several years later, she wrote about the joy of expecting a child and the grief of her infant’s death. As late as in the 1960s, it was considered most proper for a woman to hide the fact that she was pregnant with adroitly cut layers of fabric. That Hirdman could remain at her teaching job while pregnant was inconceivable. Teacher’s colleges prepared female students for the necessity of ending their careers as soon as they married. Hirdman did not publish her poems about maternity until 1928. By that time she was married and the mother of three and could write about the ordeal of childbirth. Both the mother and the child die in “Ett mote” (An Encounter) from Hjärtats ballader (1928; Ballads of the Heart).

Women get together to prepare a young bride for her first sexual experience in “Brudtäcket” (The Bride’s Quilt) from Lärkornas land (1929; Country of the Skylarks) by Berit Spong (1895-1970). Although the bride does not know what is going to happen, her mother remembers the night of torment, and the walls still echo with her smothered screams. The transition from childhood to adulthood is like leaving a quiet hobby behind for something that is “ablaze and momentous”. Two sounds meet: “As the zither drowns in the chords of the organ, my childhood sank into heavy jubilation / at the weight of his head between my breasts” – “En port” (A Door).

Spong resembles Birger Sjöberg in enjoying a wide readership and having often been mischaracterised as an idyllist and a romantic. Sjöberg started off two years earlier than Spong with Fridas bok (1922; Frida’s Book). Spong’s Högsal och örtagård (Hall and Herb Garden) was published in 1924. Both of them depict small-town life with humour and musicality, similar to Gustaf Fröding’s early reports from the province, but with an eye for what lies beneath the idyll.

The female protagonists of Spong’s “Ostagäng på Nycklinge” (The Cheese Cooperative Get-Together at Nycklinge) use work to repress their anxiety. A seamstress has to make a wedding dress for the bride of her ex-lover. A widow cannot talk about either her fond memories or the weight of her grief.

The father in “Helga den fagra” (Helga the Fair), Spong’s first poem, sends his daughter’s lover away and marries her off to Skald-Ramn (Ramn the Poet). Helga exchanges a life of love and romance for duty. All she has left as a creator is her feverish memories and her talent.

Ingeborg Björklund actually married a “Skald-Ramn” two years after obtaining her teaching degree. Arnold Ljungdal had been the editor of the left-wing magazine Clarté and a prominent Marxist theorist. After a trip to Russia (“the outpost of the future”), Björklund wrote Ropet efter lycka (1928; The Cry for Happiness), which glowingly extolled Lenin for “liberating 150 million human beings from starvation, ignorance, and degradation.”

Male critics were thrilled to death by “the Sappho of modern Swedish poetry” (Hjalmar Gullberg), “human and feminine in equal measure” (Victor Svanberg), “with girlish grace and a fierce temperament” (Sten Selander). Was it because the women in her poetry lie at the feet of their men? They are mute, ignorant mandolins out of whom men charm melodies. Women’s thoughts are only dying sparks until discussed with men. A woman describes a man’s golden-brown skin, the bronze of his slender hips, and his shiny shoes: “Take what is yours!”

But how about the fierceness? After a long, fruitless wait, she actually gets angry and complains for a while. “Huldreskratt” (The Siren’s Laugh) in Kärleksdikt (1932; Love Poem), the first of several poems about the loneliness of a mistress, is addressed to wives. “Hagars sång i öknen” (Hagar’s Song in the Desert) curses Sara’s wifely privileges. One poem tells of a woman who drives her husband away with her prattling. When he rises from his lover’s bed, restless and disgusted once more, she thinks: “Darling, I feel sorry for you” – “Till avsked” (Farewell) in Famn (1934; Embrace).

Björklund’s poems are stirring, forthright missives reminiscent of chapbooks and their tales of downtrodden women. Their daily experiences embrace the body with all of its tokens and energy flows: the milk that makes the breasts hard and full, a child’s wet nappies. The title of one of her books, Hemligt budskap (1938; Secret Message), sums up the nature of that experience. Björklund’s novels also examine her history of being an unmarried mother in a censorious society.

Another adulteress takes the stand in Tolv hav (1930; Twelve Seas) by Stina Aronson (1892-1956), prudently published under the pseudonym of Sara Sand.

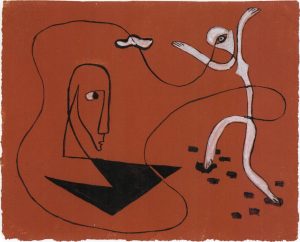

Greta Knutson, who was born into a musical family in the Djursholm area of Stockholm, went to Paris in 1922 to study painting. In 1924, the year that André Breton published his first Surrealist Manifesto, she saw Le mouchoir de nuages (Handkerchief of Clouds) a daring new experimental play by Tristan Tzara. They met in the theatre bar and married six months later in Stockholm. Based on the blueprints of Austrian architect Adolf Loos, they built a house on avenue Junot where all the leading Parisian artists – as well as Swedes like Gunnar Ekelöf, Eric Grate, Nils Dardel, and Thora Dardel – were frequent guests. In 1929, Greta Knutson-Tzara had her first one-woman exhibition at the Zborowski Gallery, and in 1933 she contributed prose poetry to Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution (Surrealism in the Service of the Revolution).

She returned to the theme in the novel Feberboken (1931; The Fever Book), this time with Mimmi Palm as her nom de plume. Infidelity raises questions in the heroine about her own identity. She says to her husband: “Go ahead, thrash me. I’m no woman, no welcoming arms, no white pool around your fountain. Give me a brutal death. I am one step from the answer to the riddle, a note that arouses uncertain longing.” The irony is unmistakable. If not a woman, is she a monster or an instrument of some elemental need? In any case, she can be irritatingly inaccessible: “I am the sealed one”.

She has betrayed her husband twelve times. “Twelve seas of anxiety surrounded me”. But even her lover’s arms are a prison and his breast is a wall, as in the poem “Det gör detsamma (It doesn’t matter):

… tear down the cloth over my blind skin

to the desire of twelve hot muzzles

Fire!

In the Inner Circle of Surrealists

If you are looking for more advanced experiments in the 1930s, artist and poet Greta Knutson (1899-1983) – a Swede living in Paris – is probably the best bet.

In 1933, Gunnar Ekelöf wrote to Elmer Diktonius that an issue of Spektrum dedicated to surrealism had been “edited in Paris by Tzara, only slightly modified by us.” Ekelöf’s friends Tristan Tzara and Greta Knutson, his wife, were to suggest articles. The subsequent book entitled Fransk surrealism (1933; French Surrealism) listed Ekelöf as the sole editor. A note at the end explains that Knutson and Ekelöf had jointly translated six poems by André Breton, Paul Éluard, and Tristan Tzara. The cover was a collective effort of Breton, Tzara, Valentin Hugo, and Knutson.

Her poetry was unknown in Sweden until 1987, when Lasse Söderberg translated and published some of her prose poems as Tärningskastet (Throw of the Dice) in Lyrikvännen (Friend of Poetry) – (No. 5 1/2, 1992) – and in the Folket i Bild Poetry Club Annual Ögats läppar sluter sig: Surrealism i svensk poesi (1993; The Eye’s Lips Close: Surrealism in Swedish Poetry). Knutson’s work appeared in the post-cubist gallery of the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition. The Gothenburg Art Gallery and Swedish-French Gallery in Stockholm exhibited her paintings. Konstrevy (Art Review) published her essays for several decades. Bestien (1980; Beasts), her first book, was brought out in Berlin, where she had met a number of young feminists. The following year she contributed to the exhibition “Andra hälften av avantgardet 1910-40” (The Other Half of the Avant-Garde) at the Stockholm Cultural Centre.

Lunaires (1985; Lunar Poems), published after Knutson’s death, is composed in a melancholy key that evokes not only her exile, but her memories of the childhood castle where she had lived “hundreds of years ago.” That land has been plundered and obliterated. Humanity itself is a ravished country and a pillaged city. “Lagunen” (The Lagoon) presents a lovely and frightening picture of a childhood when the narrator was the happy and willing slave of her parents, eager to bear their burdens. “Their hands had never stroked me; I dared not even graze them with my shadow. Every time they took a break, I lay on the ground at a respectful distance and gazed rapturously at their beauty, the guilelessness of their loving gestures.”

“Regn av aska” (Rain of Ashes) is a lament addressed to a dead person. The perspective is both far away and very close: “Of all the faces in thousands of cities, none will belong any longer to you, the only one who doesn’t know how the earth weighs on your breast.” Knutson’s essays on art are impersonal and intimate at the same time. Knowledgeably and combatively, she shifts her gaze from medieval painting to contemporary art and back again. She warned in 1951 of abstract art’s puerility and provocatively flexed biceps that constantly discover and proclaim the same tired truths. Nevertheless, she did not want Swedes to turn fear of the new French art, which had been inspired by nihilism and self-assertiveness, into a national virtue.

Knutson’s literary works share a dreamlike oscillation between time and place, unconsciousness and consciousness, with surrealism. The reader is treated to a wealth of objects and wild leaps from one noun to another: “Sitting in my row boat, I cast my net and pull it in again full of cold emeralds. At low tide, two white statues shine in the depths, wreathed by algae. Their eyes are open and lifeless.” (“Lagunen”).

“She felt him staring, very palpably, at the back of her head. She had to clench her fist to keep from scratching. It was as though she were standing in a crowded tramcar and a flea had got inside her coat collar. Or lying on the grass with her head on an anthill.

His gazes crept like ants over her, spreading from the back of her ear down her throat and arms, scampering insolently across her breasts. She felt like curling up […]”

– from the short story “Du anar ingenting” (You Don’t Have a Clue) in I drömmen var det så (1946; In my Dream It Was Like That).

A Whitewashed Church

“Oh, hide my face, it feels so naked ”, writes Rome correspondent Martha Larsson (1908-1993) in italicized script in “Musik” from Vår fjädervikt är oerhörd (1948; Our Feather Weight Is Enormous). Everybody in the concert hall stares at the person who has let the music wash her face clean. The truth and public exposure are terrifying: “I am naked in the auditorium”. A number of female characters in Larsson’s first poetry collection I denna cirkel (1944; In This Circle) hide behind laughter or hum a tune to disguise their gloominess.

The purpose of writing is to both reveal and conceal. A childhood memory helps Larsson speak in earnest. Following a rainstorm, the children had found worms on the road. Their narrow bodies, normally underground, trace “the fragile hieroglyphic of a secret wish.” Implacable wheels now threaten their lives. The children, though nauseated, restore them to safety in the bosom of the earth. The repulsive alphabet serves as a code, much as the signs that Ingeborg Erixson (1902-1992) sees at a pier in the evening sun. She calls the fish in a net “question marks in space, words and golden letters” in the title poem of Kustlandskap (1946; Coastal Landscape), published a year after her first book.

Ebba Lindqvist’s Fiskläge (1939; Fishing Village) tells of death threats in peacetime against the fishing population, of the anxiety of wives about the “woman of the sea, the shameful, naked seductress who takes their husbands.” After World War II, she wrote of Antigone, who surreptitiously buries her brother Polynices after he died in a war where brother fought against brother. “Oh, may they forget, everyone who was there. But we, who weren’t there, may we never forget”, Antigone prays in the title poem of Labyrint (1949; Labyrinth).

Two first-time poets write of a church whose paintings have been limewashed over. Ebba Lindqvist (1908-1995) pleads for help in escaping her whitewashed stiffness, even at the price of temporary fragmentation and confusion – “En vitmenad kyrka” (A Whitewashed Church) in Jord och rymd (1931; Earth and Space). Martha Larsson’s poem describes a communion, a “we” whose “hot and eager hands” chip away at the calcification and recover the childish painting – “De vilsegångna” (The Lost Ones) in I denna cirkel. “Wake up, my little woodland lake. Open your icy eyelid”, implores Maria Wine (1912-2003) in Naken som ljuset (1945; Naked as the Light), the same year that Erixson published her first collection Tjällossning (Thawed Earth).

The contours of the landscape with which Lindqvist grew up were shaped by ice, seas, and salty winds. She learned to love and hate the harsh terrain of Grebbestad on the north-west coast, where God’s face sneers coldly in the rock. Her first book apostrophises death directly: “You were the one who stole my youthful thoughts / and burned them to charred corpses”. Lindqvist was eight years old when the bodies of the soldiers who had died in the Skagerrak battle between the British and Germans washed ashore, the same event that provided Selma Lagerlöf with a theme for her novel Bannlyst (1918; Excommunicated; Eng. tr. The Outcast).

Karin Boye found fervour in Lindqvist’s writing, and Birger Bæckström heard a passionate voice. Modern composers were drawn to her words. Gösta Nystroem’s songs and choral works are now classics, their gruff tones conveying Lindqvist’s protest against the harshness of life and the desire to “find the way home on the paths of the sea” (Labyrint).

After studying in Uppsala, Ebba Lindqvist returned to her upper secondary school, hoping that she could make the classical canon available to her female students. She talks with Sappho about love in Röd klänning (1941; Red Dress). The book also contains “Debutant”, a poem sequence about teenage girls and their quest for identity. Mythical and biblical women were increasingly prominent throughout the 1950s and 1960s: Phaedra, the Danaides, Alcestis who saved her husband’s life by dying in his place, Clytemnestra, the Caryatides, and Job’s wife.

Girls learn about the lives of both sexes by reading literature, while textbooks and classroom instruction often discourage them from identifying with female characters in mythology. Meanwhile, the plethora of courses about male mythological characters turns them into experts on boyhood and the existential questions that men face. Just take Virgil the warrior and Aeneas the conqueror. Female poets have been both critical and iconoclastic in their interpretations of myth.

Without telling the whole story, a poet can use a scattering of words to render a mythological figure or dramatic situation, quickly evoking a world of ageless feelings and dilemmas.

“In me there lives a multitude,

fools, the lovelorn, hermits,

dancers.

My life is built from lives.

I am like a throng, a

cluttered market square.”

Under the pseudonym of Sara Sand, Stina Aronson used this psychoanalytical theme of various levels of self and consciousness long before Gunnar Ekelöf. “Jagen” (The Selves) in Tolv hav, however, speaks of “my pink climbing roses, my pink tales,” which offer stillness. They provide the opportunity “for me and the selves… [to hold] our hands devoutly together.” Art assuages. So having many selves may even be a source of strength, and not only for artists.

I Am Apollo’s Own Tree

The cover of Orgelpunkt (1944; Pedal Point), a poetry collection by Anna Greta Wide (1920-1965), features the words VOX VIRGINIA on a fluttering streamer in front of five organ pipes. The title poem begins by engaging Gunnar Ekelöf in a conversation:

A human soul is a fugue

of defiant voices that rise

out of the depths, that entice and consume,

and the darkness that dreams and is silent.

The voice of the maiden is one of many stops that an actual church organ may have. A pedal point in a musical composition is a sustained tone that provides a foundation for the other parts. A pedal point can also be a home port that notes spiral out from and return to after rambunctious, discordant confrontations with each other. The warring voices ultimately unite in “love’s dreaming, low, vibrating pedal point”. Ekelöf’s poem begins: “Each person is a world, peopled / by blind creatures in dim revolt.”. The thousand souls in the soul are prisoners of the ego, the king, who himself is a prisoner of something greater. The various beings cannot “gather willingly and heavily”, as in Wide’s poem.

She assumes authority with a powerful organ in a storm of sound. Ekelöf’s poem appeared in Färjesång (1941; Ferryman’s Song). Wide started off with the exquisitely composed, melodious Nattmusik (1942: Night Music). “Defiant voices obey the imperative of form” – as she writes in “Pedal Point” – in her first two books. One of the voices laments in “Nattvandring” (Nocturnal Rambling): “My soul is evil and my thoughts are sick”. The criminal in “Pedal Point” seeks consolation in the same darkness, and drawing the line between cleanliness and filth is easier said than done. A fifteen-year-old girl presses her hands to her breasts in the stifling heat of her bed: “Am I music, atoms, or flesh?”

Harriet Löwenhjelm and Karin Boye were among the most popular students at the secondary school for girls in Gothenburg that Wide was attending when she won a national competition with a poem about Aphrodite, who walked barefoot on a sunny beach among the algae and seaweed. As is the case with Löwenhjelm, Wide’s love poems are consistently addressed to female figures. Nattmusik includes a translation of Eduard Mörike’s ballad “Schön Rohtraut” (Fair Rohtraut), narrated by a young page. She can also say, “I am Daphne,” the nymph that turned into a laurel, slender as a maiden, but with her crown held high, after she cried for help while being chased by Apollo. “I am Apollo’s own tree”, she says proudly. She is no everyday nymph.

Two years later, the first poetry collection by Ingrid Nyström (1917-1999) played on the myth of Daphne, the nymph who escapes the importunate Apollo. She may be afraid of love, but not of pain or death. Turning into a laurel is a demonstration of strength and a consolation. Joyfully but silently, she raises her crown to the light:

The body you wanted to conquer

is a trunk whose life has become

a mystery

dim, inscrutable.

The hand that could have caressed

yours

has become leaves whose gentle

alien murmur you hear,

when you linger here beside me. –

“Dafne” (Daphne) in Vattenspegel (1944; Mirror of the Water).

The mysteries and metamorphoses in Dikter i juli (1955; Poems in July), her first poetry collection after many years of silence, are even more complex. Something has happened and somebody is dead. The well has run dry, the grass has withered. “The young poplar” stands without support “like the slenderest of pages”. In a poem from Broar (1956; Bridges), Orpheus cries out in anguish as Eurydice vanishes once again into the underworld, but: “Afterwards he could sing”. The water sprite hacks with his bow at overly taut umbilical cords, and the book ends with a well-known figure: Tintomara – the elusive, androgynous protagonist of Carl Jonas Love Almquist’s Drottningens juvelsmycke (1834; The Queen’s Jewellery; Eng. tr. The Queen’s Tiara) – “Loved by many, loneliest of all”.

It is not so easy to be the god of poetry’s own tree or the freshly scrubbed cliff that has longed for “a faded tuft of grass, a friendly threadbare branch of heath / and the poor little fur collar of the Spanish moss.” These contours evoke not only the sea coast, but the recesses and soft curves of a woman’s body.

Wide was highly protective of her personal life and never told her friends who had left her with “a shrivelled scar from a great symbiosis of the blood” (Broar). Perhaps she has simply realised that it is too late to be coddled like a young child again – hence all her poems about a mother’s arms, the earth mother, the primeval mother, or a comforting hand on the forehead. Or maybe she is just dreaming of consolation from a higher power. Not until Kyrie does she confess that she is being pursued by a musical key that wants something from her. She can no longer play hide and seek. Further on, she is inconsolably weary of indefinite pronouns: Someone. Something. Someone Else. Something Else. “The soul’s eternal stuttering puberty. As if I never had grown up enough to say he or him”. Eventually she dares to utter the word God but remains a sceptic and word juggler with recurring lines addressed to Ekelöf, the modernist of the “alphabet macadam”. One of them is the title poem in Den saliga osäkerheten (1964; The Blessed Uncertainty).

The secret old harmfulness

The blessed old silliness

The harmful old scabbiness

The scabby old blessedness –

Gunnar Ekelöf: Strountes (1955).

The blessed uncertainty…

The uncertain blessedness…

The unblessed certainty…

The certain unblessedness…

All of that is conceivable.

But never: the certain blessedness.

And never: the blessed certainty.

That is where truth and rhythm falter.

A no must come in somewhere.

Such is the human condition.

Anna Greta Wide: Den saliga osäkerheten.

If she was uncertain when it came to faith and belief, she made up for it as a creative artist. Her tone possesses the effortless relaxation of a person who knows her own worth and can therefore be irreverent towards everyone and everything, including herself. But she is also the lonesome Danae, who joyously receives Zeus in her bed when he arrives in the form of golden coins and scatters himself like sunbeams between her open legs:

The miracle came to me with the sun’s gallop.

The golden rain fell across the bed,

running like a sun-stream over my body,

filling my soul to the brim.

The desire I felt was not a man’s,

nor a loving woman’s –

As my mind dimmed, I blissfully perceived

the lust that cannot exist:

not a woman, not a man,

but yet a jubilant encounter –

I lay there numb and everything vanished

as the warm gold ran

between my open legs.

“Then they rapped me hard on the knuckles when I discovered the pearl between my legs and wanted to make it glitter, but this time they didn’t explain anything, but gave me only angry looks.” – Maria Wine: Man har skjutit ett lejon.

A Slain Lion

Maria Wine has described herself as a slain lion. She roars to warn another lion that hunters are near. But it is already too late, and a girl with a bleeding mouth lies where the prey had fallen. The scene appears in her autobiography, Man har skjutit ett lejon (1951, revised 1974; A Lion Has Been Shot), which tells of her life at a Danish orphanage as a young girl. She saw her mother only fleetingly and did not find out until ten years later that the man who once joined them was her father. Eventually, she was placed in a foster home, but found no security there either.

In a much later poem, the trampled woman returns as somebody who feels like a footprint. An abyss of emptiness or darkness appears, as the footprint “longs for its foot / since no foot longs / to have its print back” – “Skönhet och död” (1959; Beauty and Death). Despite its theme of submission, Wine’s love poetry is not free from recrimination.

Before I leave you alone

with your dreams

(which naturally surpass anything

I can ever give you)

I will cover your forehead

with a hundred snowflake kisses

and I will secretly show you

how to untie the knots

on all the ropes

that I would like to bind you with

Stenens källa (1954; The Rock’s Source).

She married Artur Lundkvist, an author and future member of the Swedish Academy. She moved to Sweden, where she got to know the literary world, in order to be with him. He inspired her to start writing. She had plenty of material and obtained even more from their travels and the principles of free love that he championed. Even after publishing thirty volumes of poetry, she still maintained that he was the poet in the family. She was just a versifier. In Vinden ur mörkret (1943; The Wind out of the Dark), her first book, she wrote: “You are clear and strong. I am the weak one.” He might have been heaven to her: “My heart is a well-worn trail / over which the heaven stretches its arc”. Unsurprisingly, she wrote poems that advocate free love, but deep sorrow is evident both in and between the lines.

The one who has been trampled on petrifies or screams out her pain “with plumage”, she writes in Född med svarta segel (1950; Born with Black Sails), and suffering is elevated to the level of art: “If you trample on a cherry, its white eye squeezes its way out through a blood-red sun.”

Anna Greta Wide underwent Freudian psychoanalysis with Iwan and Signe (the sister of painter Einar John) Bratt.

Their treatment centre in Alingsås attracted many authors and artists. Karin Boye stayed there for a few days before committing suicide. Eva Neander, who also died young by her own hand, was a patient as well. Iwan stressed the importance of expressing one’s sexuality, whatever form it takes, and not being afraid of the body and its natural functions. Signe moved to Gothenburg a few years after his death in 1946. She maintained her practice and supported Wide, who later succumbed to cancer at age forty-five, until dying of the same disease in 1954.

Selections of Wine’s works have overemphasised both the passionate and gentle aspects of her love poetry. The prose poems in Ring i ring (1948; Ring within Ring) about losing one’s virginity tell another story. A girl describes her experience in “Det måste hända” (It Has to Happen):

“Spread your legs further apart, he repeats; something inside me refuses, I’m frightened to death, the pain, the blood; he struggles, I resist. Let’s rest a little, he says, then we can try again. So we’re going to try again, the pain, the blood. It’s so little, he whispers. Did they scream? I ask. Did who scream? Your other women. Oh, you mean my other women; yes, some of them screamed. So they screamed afterwards, the pain, the blood, the shriek, how did they manage? I’m tired, dead tired, I’m ashamed, I want to go to sleep and forget the whole thing.”

“I’ve never wanted to have children; I wanted to stay a child as long as possible; in you I found a father”, Wine writes to Lundkvist in Den bevingade drömmen (1987; The Winged Dream). He made her an adult; later they were like sister and brother, and now the roles are reversed. He has become her child, and she the mother that she always longed for. As an older woman, she wonders in “What Is Love?” whether love is actually what she is writing about. The answers can no more than brush against words like joy, pain, and captivity. Instead, she consoles herself with the thought that life would be a weary journey had she never loved.

Dried-Up Riverbed

Ingeborg Erixson, whose mother was self-supporting, never questioned that she would continue to work as a telegraphist after marrying artist Sven Erixson.

Their friends included proletarian and south Stockholm writers like Rudolf Värnlund, Josef Kjellgren, and Ivar Lo-Johansson. They participated in a demonstration after soldiers shot five young people during a labour conflict in Ådalen in 1931, so she was not a totally unfamiliar figure when she published her first book of poetry at the age of forty-two. Being known as the practical wife of a temperamental artist may have been to her disadvantage. “Telegrafisten” (The Telegraphist) in Kustlandskap tells of a woman who is invisible to everyone and who, floating in space, broadcasts the “secret Morse code of her being”. Erixson has been grossly misinterpreted and underrated.

Only in exceptional cases do the nature images in her poetry come from the outdoors. The meadow through which the grasshopper’s silver drill bores is an inner one. “Landskap med variationer” (Landscape with Variations) in Ebb och flod (1948; Ebb and Flow) describes a love affair that alternates between hot and cold, producing hardened lava around the mouth and showers of ash over green hills. Alongside the pulsating love poetry is the sequence “The River”, which conveys a feeling of deep depression. The central poem of Främling i eget landskap (1951; Stranger in your own Landscape) is “Om värmen har lämnat dig …” (If the Heat Has Left You). The objects of the world are hiding; “it is as if they had heard you at a distance / as you approached, fled on frightened mayapples”. The poem is addressed to a frigid, solitary person who offers no consolation but looks and asks for the connection, the way to the innermost door. “Far away on the outskirts you walk, stranger in your own landscape.”

“Skogen” (The Forest) asserts that all trees are different. It may be interpreted as an answer to Edith Södergran’s loving poems in the sequence “Fantastique” from Rosenaltaret (1919; Eng. tr. The Rose Altar), with its image of the young birch that shakes its golden curls and is reminiscent of a sister. Where is “the birch that among the birches in the spring wind / shakes out her hair the same way the sister does?” Erixson asks. One is both trapped in inner chaos and outside all community: “prisoner here in the forest / among everyone else, a stranger to everyone else.” Everybody faces the same existential condition, but it affects some people more than others. Södergran writes in “I” that “I am a stranger in this land” and “Am I a stone someone threw to the bottom?” – Dikter (1916; Eng. tr. Poems). Being defined as the representative of a group, as if all birches were the Birch and all women the Woman, is also a problem.

Anne Nilsson Brügge

The Wolf’s Teeth of Tenderness

The first book that Elsa Grave (1918-2003) published was entitled Inkräktare (1943; Trespasser). The protagonist of the first poem sequence steps “onto an empty opera stage”. An unhappy clown is in the old theatre with its romantic props. The newcomer is neutral: “I hear nothing / I see nothing”. Underneath the droll attitude, however, is genuine music: “but deep from the heart’s new graves / rises the black song that lives in the shadow of dreamers’ faces.”

Having attended art school, Grave entered the literary scene uninvited and scrutinised humanity in both war and peace. Her long career earned her the reputation of a blasphemous witch in a black cape.

Her attitude towards maternity may have been a reaction to the lofty images of mothers that were in fashion at the time. With its snoring sow in a stuffy sty, “Svinborstnatt” (Pig Bristle Night) from Bortförklaring (1948; Excuse) may be the closest thing to an unclean, vegetative portrait of a woman. Something is always beneath the surface in Grave’s poetry: mine galleries or the long root system of a thistle. The sow grubs for rotten morsels, and the black corpse of a fly is covered with a drop of cream.

Den blåa himlen (1948; The Blue Sky), her next book, lends new complexity to the concept of maternity. The mother in “Djuphausmaskerad” (Deep Sea Masquerade) is truly an ugly customer:

Monkfish mother

in your bottom hideaway

you who wallow, prepared for lust,

in your swaying slumber

and devour your brood

with half-naked deep-sea jaws

Alongside grotesqueness, “Till det döda barnet” (To the Dead Child) in Bortförklaring exhibits great solemnity. An indeterminate feeling hovers over “9 vaggvisor för mitt ofödda barn” (Nine Lullabies for my Unborn Child) in Höstfärd (1961; Autumn Journey), with sea, wind, and a cosmic perspective reminiscent of Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral’s “Meciendo” (Rocking). Hungersöndag (1967; Hunger Sunday) is about a mother and child who are liberated from each other. Mödrar som vargar (1972; Mothers as Wolves) presents the dreadful side of maternity. The responsibility mothers have for their offspring is sometimes exercised with fury, as in “Djävlar” (Devils):

giving birth to our two-legged possessions

that one day become

our baby-snatching

with grown-up eyes

and backs

that are turned to us in fright

at the chattering

wolf’s teeth of tenderness

The child has given its mother wolf’s teeth and claws. The child has forced her to discover the teeth in her breast and the claws with which she will pierce its heart “if you don’t remain / my innermost lament / my song / my prey / my own beloved child”.

Grave, who was also a composer, finally gave a name (satanelles) to her muse-like curses, her litanies of “the parallel indifference” (of human beings and the cruel father): Sataneller (1989). By that time, a number of male critics had wearied of Grave’s constant wrath. They found hopelessness, even lust, in her warnings. Howling mothers are obnoxious.

Elsa Grave grew up in a mining area of Nyvång in southern Sweden. Her father, who was an engineer, took her down to the galleries, where she once found the ancient fossil of Som en flygande skalbagge (1945; Like a Flying Beetle). The fins of the fish in the rock were taut like a sail: “an instant / carved in stone / on its way through the sea of timelessness.” Ariel (1955), her first novel, describes her childhood garden, which was in the shadow of the mountain of ash from the mine. She wanted to write “impure poetry”, in the words of Pablo Neruda. In Elsa Grave’s work, the frogs sing of their icy passion, the young camel with thick little humps dreams of the desert, and anxiety sways like a tortoise or a beetle.

Evighetens barnbarn (1982; The Grandchildren of Eternity) grieves over polluted air, ravaged forests, and nuclear weapons. Elsa Grave cries to the heavenly Father that salvation comes from maternal love, not Christ’s suffering. In countries like El Salvador, whose very name means the Saviour, mothers carry the cross.

Anne Nilsson Brügge and Inga-Lisa Petersson

The Evening Primrose and the Daytime Sunflower

“What do you want to accomplish with your poetry?” radio journalist Matts Rying once asked Ella Hillbäck and Osten Sjöstrand in the Swedish town of Mariefred. Hillbäck answered: “I want to do the same thing that I wish for from others: that we will give each other courage, that we will lend each other the courage to live” – Matts Rying, Poets idag (1971; Poets Today).

Hillbäck (1914-1979) was born during one war, “when spring wore a black jacket”, and published her first book during another one. Her parents were textile workers in Mölndal. In Hos en poet i kjol (1939; With a Poet in Skirts), she asks herself what she was born to do: “I should dare” and “I should win.” Names are significant. She writes in 12 blickar på verkligheten (1972; Twelve Looks at Reality) that flowers, just like people, can be misnamed: “My middle name is Viktoria. Did that stand for victory?” Her parents’ last names were Johansson and Holmgren – the pseudonym Hillbäck may have been based on Hilda, her mother’s first name. En gång i maj (1941; One Time in May) is about St Birgitta, a model of courage and vision. On the shores of Lake Vättern are heard the water’s songs of “the great courage that lasts until the end of time.”

When the war had ended and the world had flung open its gates again, Hillbäck saw something that was to leave its mark on her poetry: fields of crosses, draped with steel helmets – Världsbild (1947; World Picture). To behold such a sight required true courage. We cannot live without experiencing the pain of others, we must live on something other than the horror of the moment – perhaps on the poem’s tone, which rose from black veils of water and made her want to weep for happiness. Or perhaps on love? “To love / is to gasp for breath / in the deep where fishes dwell.”

Raised as a socialist, Hillbäck evolved into a social critic with a Catholic and philosophical orientation. Her large oeuvre, including thirteen books of poetry and five novels, is more notable for observation and reflection than plot or ambition. Poesi (1949; Poetry) contains love poems about men and women “as good as two old trees / as naked as two desolate trunks / as mature as leaves wilting on the ground / and so sweetly poor” (“Nocturne”). The external world with its refugees and war memories ultimately resurfaces. A spring mass to the Holy Mother or a “morning bath with a thrush” might be just what is called for: “Trembling like the dewdrop, he sings from head to foot. He is himself a bath. The divine ablution of a spellbound morning.” – I denna skog (1953; In This Forest).

Her novels Albatross (1943) and Gullhöna, flyg (1955; Ladybird Fly) are masterful depictions of young women’s growth and development. Maturity is learning to see what is important. Each book features someone with particularly good vision, remarkable eyes. But not everyone is willing: “He knew everything there was to know about lenses and dioptres, she thought impatiently; couldn’t he get himself a pair of glasses to see with at home? He had to discover very soon that his mother needed a sign of life to have some lustre in her eyes […]” – Cirkusvagnen (1959; The Circus Wagon).

12 blickar på verkligheten introduced a new tone of the incredulous visitor to her writing. The cover by Jan Biberg shows twelve patches of blue sky. In 1969, Apollo II landed in Mare Tranquillitatis and brought back moon rocks and soil. Is that right? “The earth’s scourge remains. Nations are still warring. No cure for cancer has been found. Acres of hunger grow faster than office landscapes.”

Hillbäck’s cosmic overview is subsequently channelled through Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772). According to her Swedenborg-visioner (1973; Swedenborg-Visions), he chooses a latter-day adopted daughter to establish the new kingdom. “The wars arrived in earnest at the very last stage when the daughter, Swedenborg’s daughter, began her pilgrimage. All she saw was war.” The words with which he sends her out bespeak her worthiness: “She is my magic lantern that blinks in the night. She is my child on clear, frosty mornings, red as an apple. She is my evening primrose from the moor, the fragrant orchid. And she is the daytime sunflower.”

Ella Hillbäck lived at a guest house with the Bridgettine Sisters at the end of her life and was granted a Catholic burial.

Anne Nilsson Brügge

Translated by Ken Schubert