In Anna Ladegaard’s (1913-2000) debut novel, Opbrud i oktober (1966; Departure in October), we meet Ursula from an English-Rhodesian community who has spent part of her childhood in a German concentration camp where she was raised by “mothers” from different nations. As a personal consequence of World War II, she does not have a stable national identity, and her experiences transcend every limit for gender, country, language, and family. After the war, she is formed in the contradiction between the bigoted England and the more liberated France, which also offers a national identity and a gateway to the world.

France embodies limitlessness, the freedom to develop and open your eyes in all directions, the possibility to allow life as a woman to be a path to many pleasures. England, on the other hand, represents the closure that culminates in a marriage and a life in the English-Rhodesian club environment with narrow views of nations, races, classes, and gender. Naturally, the smart and beautiful Ursula breaks free of the marriage and again crosses the boundaries.

The story, which is a reflection on a Europe after World War II that is exceeding its limits for better or worse, is typical for Anna Ladegaard. However, it is also a demonstration of a historical and cultural situation that becomes valid for many, and a condition of life for a number of emigrant writers who find themselves between several nations.

Anna Ladegaard travelled out into the world, living in, among other places, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and Spain. Maria Giacobbe (born 1928) moved to Denmark from Sardinia, while Janina Katz (born 1939) and Iboja Wandall-Holm (born 1923) come from Poland and Czechoslovakia respectively. In their texts, World War II is the landmark event that wipes out nations and identities, but also creates opportunities for new self-defined goals, new cultural forms, and new lives for women and men. In Maria Giacobbe’s work, Fascism’s destruction and the clashes between tradition and modernity create conflicts and new movements, and spark the many experiments in form.

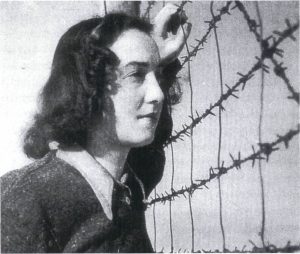

Iboja Wandall-Holm came to Denmark in 1955 in connection with her first marriage, and made her debut as a Danish poet in 1965 when Arena published the collection Digte (Poems).

She was born and raised in Czechoslovakia and survived the exile and persecution of the Second World War, the hell of the concentration camps in Ravensbrück and Auschwitz. She escaped during the infamous death march in February 1945, and arrived home to find her family killed before the war ended. One of her main works is the autobiographical Morbærtræet (1991; The Mulberry Tree), about the ability to survive and the spiritual dignity that develops in times of destruction, and which is also tested when the young woman’s revolutionary expectations of the post-war world are disappointed.

Morbærtræet is a quiet and grim tale of Europe during, and in the aftermath of, the Second World War, and of the fight for freedom, human rights, and a new post-war womanhood.

In the work of the much younger Swedish-Romanian Gabriela Melinescu (born 1942), cultural duality is a driving force in both theme and form. Världen i Sverige. En internationell antologi (1995; The World in Sweden. An International Anthology) includes one of her most recent short stories, “Berättelsernas lille man” (The Little Man of the Stories), which begins with the following line: “A human being should not die until it has become a story. A unique story. A complete story.”

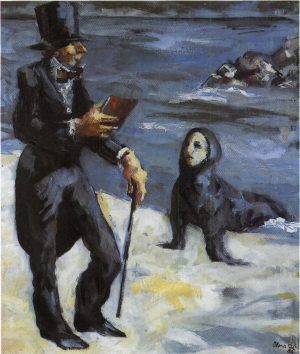

The main character of the story, Herr Bibeln, praises the virtues of history and storytelling. The story is set in a Jewish community centre somewhere in Sweden just before a meeting. In attendance are two Swedish women and Herr Bibeln. He tells his story to the women. He tells them how he was born in answer to a prayer to God, how he experienced the persecution of the Jews, how he was deported to Auschwitz, how he survived thanks to a dream of flying over the North Pole, and how he finally succeeded in doing just that. The story should be viewed as a reference to the concrete history of the Jews, but it also becomes the story and identity of the narrator in that he is telling it. And with its mixture of realism and myth, which is typical of Gabriela Melinescu’s work, the story reflects the increasing fragmentation of the narrative form that becomes part of the dual cultural perspective. The story is set in Sweden, but with an increasingly roaming perspective, such as in the poetry collection Ljus mot Ljus (1993; Light Against Light), where Gabriela Melinescu places “August Strindbergs sidste promenade i sne” (August Strindberg’s Final Promenade in Snow) alongside “Rabbinerens sang” (The Song of the Rabbi).

Gabriela Melinescu came to Sweden in 1975, but had already made her debut in Romania in 1965. She has written a large number of books in both Romanian and Swedish, including poetry, novels, diaries, and short stories. Today, she writes primarily in Swedish. Her stories are often set in her native country, and are associated with a tradition in which the most trivial and the most unlikely is combined without commentary or explanation. Realism and myth co-exist.

She shares her unyielding insistence on the necessity of narrative and of change with Anna Ladegaard, whose novels are also always reconstructions of historical events, mysterious, fateful, and in the course of her career, increasingly filled with reflection on narrative itself and the nature of confiding and disclosure. In contrast, the Swedish authors Rita Tornborg (born 1926), who is of Polish descent, and Sigrid Combüchen (born 1942), who comes from Germany, make rootlessness and alienation a point of form by breaking with the epic narrative structure and the principle of well-rounded characters. The view of the world becomes kaleidoscopic, while linguistic alienation is used as a linguistic responsiveness and creative force that weighs every word and excludes all automatism. In the work of Tornborg and Combüchen, the cultural clash becomes an expression of modernity, and thereby also an experience that can only be expressed in the language of modernism.

World, Dream, and Story

Anna Ladegaard may be a utopian. In the majority of her novels, her characters managed to establish a form of life that suits them specifically and that also establishes its own social order, which may not be in accordance with societal conventions in general, but rather represents an order that is created from scratch. It is created in transcendence of history, national borders, generations, and gender.

At the same time, the stories keep the reader on her toes by asking the big question about how the new order can be established, what unknown threads knotted. The suspense in the books lies in the nooks and crannies of the past and in the process of paving the way towards a possible future. The books are always concrete, ordinary, and focused on the characters’ daily activities, their day-to-day considerations. However, it is exactly this modest (without big words) and detailed form of writing that establishes in the reader an increasing expectation to see a pattern develop and come to fruition.

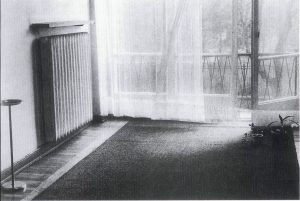

The shock effect is especially powerful in Drømmen om … (1980; Dreaming of…) when Anna Ladegaard allows the pattern to be shattered. The novel’s tragedy is hinted at, but only faintly, in the brief introduction, where a father shows his son a house he has not seen for ten years. In the house in a Northern Jutland provincial town the young couple Martin and Nina attempted to establish a life in a world far away from their life in Copenhagen. The provincialism oppresses their lives with its inquisitiveness, gossip, and malevolence. It does not permit ambition, breaks with convention, or differentness. It allows prejudice to control interpretations and evaluations of the not particularly wild lives of the new arrivals. In this society, Nina attempts to find a modus vivendi and makes acquaintances among the more friendly and open-minded residents. Nevertheless, things go wrong, and Nina dies dramatically after a premature birth caused by a fall. The long tale emphasises a marching in place. The house, which is renovated with care, becomes, as is often the case in Anna Ladegaard’s world, a carrier of the utopia, but the unyielding social order kills the dream. The utopia can only be realised when it becomes possible to confront the personal ghosts of the past and start a life on one’s own terms.

The characters in Anna Ladegaard’s novels are also in the paradoxical situation of insisting on their right to be themselves, which can, as in Günthers anden verden (1983; Günther’s Other World), degenerate to eccentric isolation, as well as striving to establish the story, the narrative of their lives, their roots, their future. As her work progresses, the jigsaw-like structure, with the many interwoven narratives that correct each other, becomes increasingly dominant.

Anna Ladegaard’s narrative utopia can be almost beseeching, as emphasised by her often extremely creative plots, which again are woven together with family histories with threads that reach down through history and horizontally across national borders. History, the family, is one of the creators of the narrative; quite literally in the novel Her på bjerget (1988; Here on the Mountain), in which the story begins with a somewhat complex inheritance from a Spanish grandmother to a Danish granddaughter, who takes up residence for half a year at a time in the family home in a remote Spanish village, far from both Denmark and Spanish society in general, but with room for eccentric individuals to live their lives. The logic of the narrative appears to be that things must become complicated before release can be achieved.

Narrative is powerful as an instrument of truth. In Anna Ladegaard’s radio novel Svens familie (1976; Sven’s Family), the first-person narrator writes a family history that turns out to be dominated by desire, hate, silence, and concealment as a constant and vicious inheritance. An end to this spiral finally comes through the story’s revelation of the right connections, a revelation that averts yet another disaster: the truth about the past shows the way to a better and freer future.

Love and Luck

Living the good life requires strength and a strong will, and Anna Ladegaard’s characters all have or find that strength. For the women, this means rebelling against the narrow family affairs (mothers, husbands), but not in the sense of 1970s feminism.

Still, it is often the women who rebel, especially in her early works. In Opbrud i oktober, Ursula is both a victim of the norms and free because she does not become a transmitter of them: she does not represent power and convention. Where the women are in power, such as in the domain of motherhood in Alle mine (1972; All Mine), they are more than vicious enough. However, convention is not bound to gender in the works of Anna Ladegaard; she searches everywhere for the ability to strike a balance between one’s own world and an essential connection to others, which again presupposes that one’s own “house” is in order. And she does not refrain from attributing talents and enlightenment to heroes and heroines who, in these virtues as well, depart from society in general and from a more pedestrian convention.

The rebellion is individual and based on ethics and a measure of human development that transcends many boundaries, but not necessarily those of family life, love, or home. As a result, family tends to become, on the one hand, an overwhelming enforced nuisance and, on the other, the big dream. Ursula breaks free by virtue of her beauty and refinement; the aesthetic, in the form of creativity and imagination, is often part of what makes Ladegaard’s characters special. The rebellion is erotic as well. The brusque writing style is traversed by sensuality, creativity, and eros as vital ingredients in Anna Ladegaard’s utopia. Heroes and heroines are categorised as erotic as a special qualification, and where eros and creativity are united in erotic imaginativeness, the narrator dares to truly vouch for the happy ending.

Janina Katz (born 1939) was born in Krakow, Poland and arrived in Denmark in 1969. She is a translator, but writes her poetry in Danish. Childhood, the past, and memories play an important role in her universe, which is also characterised by a journey through the past and the present – both unsentimental and dreamy. Poetry becomes a way to bring together sides and aspects of life, to juxtapose them and allow them to shed light on each other, thus revealing unexpected patterns and connections in a woman’s fluctuating life, such as in the poem “Jeg er helstøbt” (I Am in One Piece) in Mit uvirkelige liv (1992; My Unreal Life):

I am in one piece

But formed

– it is true –

by all the winds

that blew through

me

and tore apart my

country

and my home.

By gods golden calves

and other idols.

By my mother’s kisses

and slaps

– and please note –

both deserved.

By one man’s death

and many men’s embraces.

By an evening breeze

from a southern ocean

that lives in my imagination

and on whose

coast

I once was born.

I am in one piece

believe me.

This is something

I truly understand

after having been

so often

broken.

Shepherd in Paris

In one of her many stories about the culture clash between an underdeveloped culture and the new Europe, Maria Giacobbe presents the first-person narrator’s point of view with the following sentence: “The house where I was born, where my mother was born, where my grandmother arrived as a bride, and which my grandfather enlarged and decorated for her using half of what he and his brother had inherited from their father, that house is still standing, although it is almost unrecognisable when you, as I, had been away when it developed, after yet another division among the siblings, an outer layer of extensions and became hidden among them, like a seed in the flesh of the fruit.”

The name of the story is Dagbog mellem to verdener (1975; Diary Between Two Worlds), and even its linguistic structure demonstrates the nature and conditions of the process of remembering. Deep within the hypotaxis of the sentence can be found the core, the past that the first-person narrator and the reader sink into and from which the story, like the house, is slowly built up, hiding the original, although without it becoming completely inaccessible. From an indefinable point in the present, the past is reconstructed, life under Fascism, the family’s resistance, and the girl’s constant consciousness of the constraints that tradition places upon her when it comes to love and career.

Maria Giacobbe grew up on the Italian island of Sardinia and trained as a teacher before she met and married the Danish poet Uffe Harder. The majority of her work is written in Italian and translated by Uffe Harder, and later by their son, Thomas Harder. The language also tells the story of both division and unification between the two worlds.

Her debut in Danish, the collection of poetry Stemmer og breve fra den europæiske provins (1978; Voices and Letters from Provincial Europe) speaks from a place in Europe that resembles Sardinia. She watches the centre, the technological and economic development, from the sidelines, while she observes the traditional enclaves in Europe from the point of view of the well-educated and cosmopolitan European. From this dual point of view, she takes a critical approach to Europe’s history while at the same time using her cross-cultural experience from her Sardinian childhood in the days of Fascism to an adult life as a writer in the Danish welfare society.

To her, the traditional Sardinian society becomes the story of her own identity and culture. It becomes a world she constantly relates to, and always with a view to the reality and limitations of this world, without nostalgia – critical, but also as an assignment: how does one even relate to this type of experience?

A solution is presented in Dagbog mellem to verdener by a shepherd who emigrates to Paris while Italy is under Fascist rule. In the choice between nostalgia, resistance to all things new, and integration, he chooses a rather special and pragmatic solution: he makes a good living as a shepherd in Paris, but he also becomes a politically active anti-Fascist and a secret courier. The shepherd turns his dual foreignness into a virtue as well as making it a political point. What he is fighting against from the midst of his flock of sheep is neither the old nor the new, but oppression: Fascism as a threat to freedom, humanism, democracy, and the free development of the individual. He resembles the author in his radical intervention in history.

In a fantastic and dream-like atmosphere, Maria Giacobbe plays through the theme of alienation in Eurydike (1970; Eurydice), a story from the 1968 generation that places woman and love above global violence, oppression, and war. The sense of alienation is also a central theme in the dream-like stories in Den blinde fra Smyrna (1982; The Blind One from Smyrna).

Consciousness of genre and language is key to Maria Giacobbe’s writing. Access to language and storytelling becomes part of the narrative itself. The meaning of language is already a theme in her first novel, Lærerinde på Sardinien (1959; Diary of a Teacher in Sardinia), wherein the young Maria Giacobbe attempts to bring reading and learning to poor, partially fragmented Sardinian villages. In terms of social history, the book documents poverty, analphabetism, and underdeveloped cultures in which some places have not even introduced the bed as part of the household furnishings. But it also documents the dialectic of enlightenment. The children can only learn when met with kindness and respect, when their own cultural experiences, from before they learned to speak and write, are permitted in the classroom. What the teacher and the reader meet is a shocking material and cultural poverty that often robs the children of their childhood. Toys do not exist, the little girls work as maids in other households, the children cannot even speak Italian. Everything cries out for change, cultivation. There is apparently nothing that can be damaged. And yet the teacher presents a multi-page strategy. She implements changes by changing cultural patterns when she obtains beds and toys for a poor village, she opens up the outside world when she has a talented boy sent to the mainland, but she also allows the children to use the school, writing, and paper to retain their experiences from the past cultural life.

In the anthology Septemberfortællingerne (1988; The September Stories), in which seven writers each tell seven stories that together make up a modern Decameron, Maria Giacobbe contributed with a playful Egyptian storyteller who tells the tale of her life, from her beginnings as a poor and culturally deprived girl in Luxor on the verge of starvation to becoming an independent photographer. The motif is thus a common one for Maria Giacobbe. One of the themes of her story is the older husband as the woman’s lover, teacher, and helper – and each story hides its point so that the moral becomes the story itself rather than an obvious message.

In the novel Øen (1992; The Island), the teacher’s dilemma returns many times over. The stark story is about the murder of a shepherd boy who had witnessed the escape of a group of cattle thieves. The boy’s death is avenged by his quiet brother Oreste under pressure from a woman, just like in the Greek myth. Here it is not the sister, but rather the mother who encourages him, and the young murderer is sent on the run to Dr Rudas, a well-educated Sardinian woman who is following in the footsteps of her dead father. Through a polyphony of voices, Maria Giacobbe gives a voice to the mute who would otherwise not have the opportunity to speak out. But the silence of the poor is not only caused by mainland-European culture. The voices that carefully relate the events, motives, and arguments for the individual’s actions technically speak to no one, because the knowledge they express is taboo, subject to silence. Fear and honour control the small society which, even through blood vengeance, establishes a social equilibrium that cannot be created through the police and the official law, partly because the witnesses will not speak. The voices are a defence for the often terrible rules that govern their lives, as well as documentation of the futile dreams of the young people about a life beyond the traditional shepherd’s life.

This paradoxical polyphonic choir of silence is confronted by modern European thinking in the form of Dr Rudas, and it initially demonstrates that the beautiful young career woman is the strongest supporter and enforcer of the law, while the men, her dead father and her boyfriend Lorenzo, represent a third path that has humanity and love as images of a law beyond blood vengeance and the Italian legal system. Love and life, her eventual pregnancy, become stark contrasts to both the traditional society’s destructive taboos and modernity’s abstract legal practices.

In the tale of the relationship between Dr Rudas and the island, Maria Giacobbe depicts the dilemma of a modern, intellectual, and culturally divided woman – a woman who experiences anonymisation, abstract justice, as a release from the family’s silent, controlling concepts of honour. The husband, on the other hand, easily chooses the world of animals, island, child, and love without them becoming a threat to his modern knowledge and independence.

Maria Giacobbe’s cultural-critical utopia contains a message about a justice that is more civilised than that of civilisation, because it is based on love, happiness, and the body. The criticism is concrete and political, but it is also about identity trapped between tradition and modernity, as well as about modernity and the ambivalent relationship of the sexes to the old and the new. Her cultural discussion also involves the collective unconsciousness and mythical processes – history’s path through myths and religions and its confusion of man-made norms with a divine rationality. Throughout her body of work, erotic love is a vital and central part of any release. In the poor island society, the body and love are among the most neglected concerns. They belong to silence and the Devil, who torments the priest’s frail flesh.The theme of Havet (1967; The Sea) is the awakening of the erotic body.

In contrast, stunted eroticism is a driving force in the nameless woman’s betrayal of the French half-Jew Odette and her Italian lover in “Lærredet. Odette. 1940-50” (The Canvas. Odette. 1940-50), the first of three historical tales about women and the conditions of love in Kald det så bare kærlighed (1986; Call It Love Then). In a combination of terror and determinedness, the young Italian Dolores in “Udflugten. Dolores. 1950-60” (The Excursion. Dolores. 1950-60) goes on an erotic adventure with a black musician in the Danish landscape, away from her controlling Catholic society. The erotic also survives the separation of the lovers in the poetry collection Ariadnes døtre (1987; Ariadne’s Daughters). The poems progress in a singular dialectic from the flames of summer to the burnt-out fires of autumn. In the poems, there is a beautiful equilibrium between the two lovers; their longing, desires, reservations, and changes run parallel, although, and especially because, Ariadne, and not her daughters, curses the faithless Teseus. In Maria Giacobbe’s both loving and ironically-knowing version, the daughters know that they too will change. However, the progression of the poems becomes more than just a tragic transformation towards the end of love; it also culminates in an image of fertility, of his life in her, and of autumn’s readiness for new life: “… so ordinary / so wonderful” concludes the warm, ironic apotheosis to love.

Maria Giacobbe’s special dialectic also comes to light in the autobiographical childhood story Masker og nøgne engle (1994; Masks and Naked Angles), about a little girl whose father goes off to fight in the war on Fascism. From the child’s point of view, this is a fatal loss of love and an abandonment of the family: “[…] his absence caused an almost constant bitter taste of sorrow and hopelessness”. The mother lectures them about “the nobility of the choice that our parents made together”, but the contrast between approving of the heroic act and the feeling of pain does not subside. Instead, it forms the basis for insight into the complexity of existence, into the lack of identity between feelings and politics.

Anne Birgitte Richard

Rita Tornborg

Rita Tornborg (born 1926) made her debut at the age of forty-four with Paukes gerilla (1970; Pauke’s Guerrilla). Her environment is the big city, often a contemporary Stockholm with a myriad of recognisable addresses. Her characters live on Lötsjövägen road in the Hallonbergen district, do business on David Bagares gata street and run down Riddargatsbacken. It is not until the door opens to the homes of the various characters that Stockholm turns out to be more conducive to fantasy and above all more culturally diverse than one normally can or will see. In the Stockholm of Rita Tornborg, there are at least as many hot-blooded immigrants as cold-blooded Swedes, and their meetings are depicted with ironic sympathy.

Rita Tornborg (not unlike a writer such as Kirsten Thorup) takes up the heritage of the nineteenth-century novel, in particular through her descriptions of settings and characters and her interest in the big city and the attitudes to life that are formed and confronted there. Her narrator is manifest and omniscient, and the dialogue takes place primarily between the narrator and the reader.

Rita Tornborg has sometimes been criticised for creating characters that are dangerously close to clichés. In such cases, the criticism takes psychological realism as an ideal, and that point of view is not likely to be shared by Rita Tornborg, whose stories are more closely associated with an older tradition. Her most important tool is the imagination: her aesthetic is surprise on all levels of the text, from the individual sentence to the plot. The words smell like gunpowder and perfume; pregnant with the present, they also carry the past with them. Characters appear, live for a moment by virtue of their special way of being, speaking, and acting, and then disappear, only to reappear in other contexts and in other stories. They do not represent clichés of a type, but different, often unexpected approaches to life.

Tornborg’s prose in Systrarna (1982; The Sisters) has been described by Staffan Söderblom as verbose and “virtuously driven conversation with an invisible interlocutor”. Rita Tornborg demonstrates a powerful and feminine faith in conversation’s ability to influence and initiate change that is typical of the period.

In her work, the obligating conversation goes hand in hand with the attitude of the moralist. Everyone is equal, but some people are equal in a more original way than others. All people are, to a certain extent, alienated from reality, but some people are more alienated than others. Rita Tornborg has shown so much interest in immigrated foreigners, especially the Jews – in the novels Hansson och Goldman (1974; Hansson and Goldman), Friedmans hus (1976; Friedman’s House), and Salomos namnsdag (1979; Salomo’s Name Day) – that she has been mistakenly assumed by many to have a Jewish background, when in reality it is “only” a matter of sympathetic insight into the foreigner’s situation and an interest in the Jewish way of thinking. There is, however, one categorical imperative in Rita Tornborg’s moral universe: every person must take responsibility for their own life. This imperative is expressed in her work through a sudden protest action, a resounding No! that changes the direction of the lives of one or more of her characters. The individualistic message’s dimension of political and cultural criticism is clear: the Social-Democratic welfare state project will not find an enthusiastic supporter in Rita Tornborg.

In her first five books, the world is primarily viewed through male eyes; however, in Systrarna and especially in the subsequent Rosalie (1991), the perspective is that of a woman. It is not just a matter of a shift in the point of view of the narrator, but also of a new thematic orientation.

Rosalie depicts a disparity between the sexes, a female way of viewing and dealing with life and death and love that stands in opposition to a dominant male view. Men live solely in their own centres, in the “modules of power” where they “turn people’s fates like the pages of a book”. Women move on the periphery and live through powerful emotional meetings with other people’s fates. In the novel, the female life is presented as a series of losses that feed a fundamental feeling of want. However, rather than causing paralysis and passiveness, it inspires an unusual drive and ability to change.

Sigrid Combüchen

Sigrid Combüchen’s (born 1942) work comprises a collection of essays and a large and diverse collection of very different novels. They can be viewed as individual experiments in form in the aftermath of modernism, but there is also a complex connection between the ideas they contain and the form of these novels, as though every new initiative, every new issue required its own special solution independent of the prevailing trends.

Sigrid Combüchen’s novels represent something of an intellectual project, a controlled insight that could dishearten the reader if it had not been integrated into the artistic unity in such a sophisticated manner. Her novels stand on their own, but at the same time, when viewed from a reverse perspective, register imminent tremors in the body politic with seismographic sensitivity.

Both Rita Tornborg and Sigrid Combüchen demonstrate a brilliant lack of interest in the traditional composition of the novel: plots are introduced without being connected together, the characters are rarely complete. This may seem like a female way of writing, but it can just as well be a narrative approach resulting from foreignness. Whereas many Swedish writers grow out of a single geographical and cultural native country, the perspective of Rita Tornborg and Sigrid Combüchen is rootlessness and their vision is kaleidoscopic.

Sigrid Combüchen made her debut at the young age of eighteen with Ett rumsrent sällskap (1960; Civilised Company). However seventeen years would pass before she published another novel. At the time, in 1977 when “realism” and “authenticity” were still applauded in the art of prose, I norra Europa (In Northern Europe) appeared as something special, a harbinger of the “approaching summer of fantastical literature”, as Birgitta Trotzig wrote. However, this fantastical element does not operate within the framework of a traditional epic story (as in fantastical realism, which even then was the object of a great deal of attention). The plot of the novel about the three royal children, Adrian and Ragnar and the “princess”, is – if it is even possible to speak of a plot at all – set in a timeless literary world in which the myths of romantic novels and popular culture form a fragmented pattern without inner coherence. It is an example of fantasy literature that asserts the ability of language to create a separate world that approaches our own in a complex, artistically transmitted manner. The novel is built up of rhetorical elements that would come into fashion later – quotations, pastiches, ambiguity – and Sigrid Combüchen uses them brilliantly. However, technical virtuosity is not a goal in itself: the novel thematises a modern, divided consciousness and a kind of fetishism of experience that excludes deep connections and fellowship in favour of a consumerist and instrumentalist view of humanity. Without pointing the finger, it allows for a political reading along the lines of a critique of a process of progress that has lost sight of its liberational objective, instead becoming divided into the throw-away dream production of a growing leisure and culture industry.

In Sigrid Combüchen’s next novel, Varme (1980; Warmth), the composition is also shattered, but here there is a kind of central perspective in the form of the first-person narrator, Göran Sager Larsson, who sits reflecting on his childhood and youth on New Year’s Eve 1979, a few hours before his thirty-ninth birthday. He reminisces in fragments, episodes, and exchanges in dialogue, and his point of departure is a present in which he is not truly happy. He finds himself surrounded by people who are trying to construct exemplary and coherent backgrounds for themselves, people from the right class, women who “in the end have become pregnant with their femininity”, people who have had radical intentions since primary school. Göran’s memory snapshots, and his reasoning regarding them, sabotage this apparent order – anticipating an approaching disorder.

In this novel, as in her other novels, Sigrid Combüchen works with distancing effects on several levels. Between herself and the world she interposes a male consciousness – Göran’s – although it is female enough to be viewed as a mask for a more personal ‘I’. As a little side note, in Korta och långa kapitel (1992; Short and Long Chapters), the “author” comments in an almost confirmatory tone on Göran, saying that in Varme he “mostly supported his own case, and yet treated me with a degree of delicacy and discretion”, so much so that he returned as one of the main characters in the new novel. The contemporary world is viewed through the distant mirror of childhood, and most importantly, there is a vast, revealing distance between the words said and what the character speaking them actually means. Sigrid Combüchen has an unusually good ear for unconscious class and gender markers in language. This linguistic awareness has most likely been sharpened through studies of the English social satire novel, such as those by P. G. Wodehouse, in whom Sigrid Combüchen has documented an enthusiastic interest in her literary criticism.

In the monumental novel Byron (1988; Eng. tr. Byron – A Novel), a detour is taken through history in two stages in order to reach the absolutely contemporary. Lord Byron’s character and fate is discussed and interpreted through six members of the Byron Society in 1930s England. They each take turns placing an additional filter, in the form of historical personages in Byron’s immediate surroundings, between themselves and their romantic hero. Thus, Byron remains fragmented and elusive, which a number of critics called attention to. However, Combüchen’s work is not so much a biography of an author in novel form, as it is a novel of ideas. What it discusses is, among other things, equality in love and politics as impossible or at least as incomplete projects. It pits revolutionary idealism and innocence against realistic assimilation and consciousness of guilt, thus thematising its contemporary revolutionary dreams. Sigrid Combüchen then takes an unmediated leap directly into the currents of her time in her next novel, Korta och långa kapitel. Three very different characters, the young student Heidi who works as a personal care worker, the university professor Göran (known from Varme and now around fifty years old), and the thirty-five-year-old alcoholic Bengt, come into contact with each other in a typical suburban setting. In a way, they represent an empathetic, an intellectually distanced, and a subconscious or spontaneously unreflective approach to the reality that confronts them. The narrator is apparently most sympathetic towards the empathetic Heidi, although that does not put her in the position of a mouthpiece. If anything, they represent three different sides of the same (first-person) narrator, who explores the confusing multiplicity of contemporary life: bureaucratic strategies and individual fates, cultural clashes and rigid traditions, mournful distance, ice-cold intimacy, and genuine warmth.

In this novel, Sigrid Combüchen’s linguistic consciousness reaches new heights. Various idioms and tones of voice and their deeper meaning are represented perfectly. The form of this novel is more open than her previous work: characters appear, meet randomly, and move on towards an unknown future. Sigrid Combüchen has compared the work to a roundabout. The result is a contemporary portrait that inspires a sense of closeness and motion.

Ingrid Elam

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd