It may seem like a paradox that the women’s movement became an inspiration to art and literature, given that it started out as a political and collective movement. One explanation is that rather than exclude the aesthetic, the politicisation redefined it so literary modes of expression were understood as part of a larger cycle between the author’s experiences, the reader’s identification, and the literary public’s power structure. Based on the new research in women’s studies being conducted at the universities, a league of female reviewers arose who wrote about new – and old – women’s literature, thus functioning as the propagators of reader experiences as well as the new norm-setters with regard to interpreting women’s literature.

The notion of the importance of the woman’s experience, in particular, became an artistic driving force. It led to the creation both of the confessional genre, in which the subjective experience served as a way for the writer and the reader to conquer identity and ‘I’-power, as well as of emancipation literature, in which experience paradigmatically leads to awareness, resistance, and liberation, from marriage or from mental self-oppression. The actual discovery of the female universe as both a special and valid theme inspired ‘old’ modernists like Cecil Bødker – who wrote Evas ekko (1980; Echoes of Eve) – newer authors such as Dorrit Willumsen, Jytte Borberg, Charlotte Strandgaard, and Kirsten Thorup, as well as a large number of debut authors from Jette Drewsen, Hanne Marie Svendsen, and Vita Andersen to Anne Marie Ejrnæs, in whose first novel the paradigm of the 1970s definitively breaks down.

The women’s movement at the end of the 1800s became a literary breakthrough, a fight for women’s writing and (political) voice. Many years after women gained access to the academic world, research in women’s studies, which combines academia and politics, developed in the 1970s. From then on, women and gender have been a subject of academic study while the new research questions, at the same time, questions the meaning of gender within the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. With women’s studies, scientific enquiry becomes more than a discourse to which women have access; science itself is challenged and changed.

The female literary public, like Janus, had two faces – one of liberation and one of pain. For instance, two suicide novels were very popular subjects of debate: Jette Drewsen’s second novel Fuglen (1974; The Bird), about the artist Mia, and Herdis Møllehave’s (born 1936) Le (1977; Laugh), about the thirty-year-old, highly educated, divorced mother who takes her own life after a complicated relationship with an emotionally reserved man who, in self-defence against the new strong woman, hides his feelings and vulnerability behind the knot in his tie. However, Le is also a story about a woman suffering from alcohol problems, anxiety, and depressions, who throws herself into a love affair with a temperamental, alcoholic artist who does not love her, and who makes him her fate. Part of the novel’s appeal – it sold more than 100,000 copies in Denmark and has been translated into Swedish, Norwegian, and Icelandic, among other languages – lies in these unanswered questions about the differences and the relationship between the sexes. Herdis Møllehave continued the debate on the new love issues of the times in her novels Lene (1980) and Helene (1983), yet another novel about marriage.

With the new league of female reviewers, literature, the press, and academia became interwoven. Pil Dahlerup and Jette Lundbo Levy were reviewers in the Danish daily Information during the same time period when women’s literature was becoming a subject of study in the academic world. Birgitte Hesselaa and the author Inge Eriksen also wrote for the same newspaper, while Bettina Heltberg was an important reviewer of the new women’s books in another Danish daily, Politiken.

The World is Your Tale

In Hanne Marie Svendsen’s (born 1933) stories, gender is a constant focal point, also where consciousness and emancipation are interpreted as an openness to fantasy and sensuality. History, daily life, and art are considered part of the specific dialectic of gender relations. In Guldkuglen (1985; Eng. tr. The Gold Ball), the central symbol in the book is accompanied by the following story: one day, a man with a voracious appetite for power, women, and wealth sees in a cave a statue of a woman with an abundance of breasts. He wants to crush this demonstration of female power, sexuality, fertility, but instead the statue falls on top of him and leaves him with a gold ball on a chain around his neck. Like Ahasuerus, he is condemned to continue his voracious wanderings for eternity, without being able to die, until he finally realises that the ball is a symbol of his own life, of his rejection of life and female fertility. Only then is he able to die – and pass the ball on. It even appears to give eternal life to his diametrical opposite, the woman Maja Stina, who survives for generation after generation constantly caring for new children – and finally for her namesake the narrator.

Guldkuglen was Hanne Marie Svendsen’s breakthrough as an author. In its form, it breaks with her previous, realistic stories about female consciousness-raising and revolution, but the relationship between the male and female outlooks and ways of life forms the core of her entire body of work. It is an imaginative and fantastic story, a story of creation and apocalypse, of one island’s creation and development and ultimate collapse. The novel is told in the present in which the two Maja Stinas spin around in space and time at the top of a tree which may be the Yggdrasil world tree, and it retells the stories of the people of the island and thus the previous history of the ‘I’. These stories deal, especially, with development as an interaction between the male appetite and different types of female – or artistic – approaches to life, love, and history. The oldest forefathers are violent in their appetite for women, power, and wealth. They want constant conquest and change, although they, like the unfortunate Ahasuerus of the myth of the gold ball, sometimes run into a female, witch-like, mystical power they cannot conquer. The story also questions the female stagnation that can degenerate into obdurate insistence on the immutability of sofa cushions. Attached to this immutability is a sentence that is repeated as a refrain throughout the novel: “That’s how it is. It won’t be any different. And it is the way it is. The many fantastic tales about the lives and fates of the generations are woven into the story’s reflections on the nature of time, order, and sensation. Thus, the island and the gold ball also become symbols of the bending of time, its circular nature, which the narrator is forced to overlook in order to tell a traditional, linear story about the people of the island. And this conflict is again part of the reflections on gender, sensation, desire, myth, and power that appear as a pattern in the individual stories.

Hanne Marie Svendsen’s debut novel, Mathildes drømmebog (1977; Mathilde’s Dream Book), is a distinctive work, not least in its unique layout. The typeface is in two colours – the brown sections tell the story of Mathilde’s daily life, from when she, at a young age, wanted to break with the conformity of the older generation, until she, in middle age, finds herself trapped in a routine job, routine family, and a seriously hypothermic relationship to her husband. The blue dream sections not only foreshadow her fate, but also give life to another dimension of colours, sense and, especially, nature that she slowly loses contact with in her waking world. Hanne Marie Svendsen associates her concept of emancipation with this alternative mode of sensation and realisation, which is an enduring aspect throughout her oeuvre, even when the nature of her stories change, becoming experimental, fantastic, and mystical. This is also where her poetics is imbedded. It is less pronounced in Dans under frostmånen, (1979; Dance beneath the Frost Moon), about the reserved daughter of a priest and her startling experiences with eroticism, politics, and history, and Klovnefisk (1980; Clownfish), in which the confident career woman is compelled to reverse the way she views herself in relation to the others as hippies and losers. But it returns in full force in the collection of short stories Samtale med Gud og med Fandens Oldemor, (1982; Conversations with God and with the Devil’s Dam), which takes as its point of departure the little fable about ‘The Lunatics’ who invade the ‘I’ with crazy projects she refuses to acknowledge – until she meets them again in her mind, brought to life by a musical experience. And in Guldkuglen, where everything – dreams, the sensations, and the narrator’s reflections on the meaning of the story, the words, and the myth – unfolds concurrently.

In Hanne Marie Svendsen’s Under solen (1992; Eng. tr. Under the Sun), a destructive boy in a small town becomes a building tycoon with plans to subjugate nature and transform it into a shopping and entertainment centre. He is murdered by the main character, Margrethe, whose life we follow from childhood to old age.

However, her new form, which is inspired by, among other things, the fantastic literature of South America, continues two of the most important trends in 1970s literature: the idea of the break-up as a revolt against political and mental conformity and oppression, and the focus on the relationship between the sexes as a polarisation – and a dialectic. The male drive for development, conquest, profit, machines, and the increasingly catastrophic usurping of nature do not go unchallenged as the ‘evil power of history over female reproduction’. With reference to Plato’s image of the sexes as a split double creature that longs for unity, and in the belief in sensation and art as a common need for men and women, there also lies a utopia or, at least, a hope. In the drama about Rosmarin og heksevin (1987; Rosemary and Witches’ Wine), in which Odysseus gets Circe to fall in love with him and in so doing manages to avoid being transformed into a pig, the dialectics of the sexes unfolds further. In a process of resistance, the women deny history and progress, that they are born of women and are part of the passing of the generations, and that they themselves can die. Into this static universe enters Odysseus, with his proposals for transformation and his Penelope-like dream image of a woman. Both views of life are changed by the meeting: for Odysseus, Circe lives on as “a thorn in the sole of his foot”.

In Lisbeth Bendixen’s (born 1923) second novel Kassen stemmer alle ugens dage (1979; The Cash Drawer Tallies Every Day of the Week), three women cashiers are freed of guilt and self-oppression through an Easter ritual carried out by an odd old lady with the mysterious-sounding name Maria. Brooding religiosity, constricting provincial norms, and rigid gender roles tie the women to a convention in which sensuality and sensibility founder. This is also the case with Karen in Dans med mig (1984; Dance with Me), who mirrors herself in the wild Camilla who is perhaps just a killed-off part of herself. Myth and art become part of the liberation process and a dimension that is also central in the collection of short stories Stjerneloftet (1987; Ceiling of Stars).

Transformation and awareness are also the theme for the young Kaila in Kaila på fyret (1987; Kaila in the Lighthouse) and for the nameless man in Karantæne (1995; Quarantine). Both are brought to isolated places, where they are confronted by the lives they have lived so far and develop the courage to move beyond routine and unreality, that is, towards both greater sensitivity and greater awareness.

Tove Pilgaard’s (born 1929) two novels about the girl Lone, Brudstykker af et pigeliv (1982; Fragments of a Girl’s Life) and Modsætninger (1985; Opposites) tell a story of a woman’s life in which pregnancy and marriage put an end to dreams about personal growth and education. It is the story of an unfulfilled self in which pressures from the outside have a negative effect on self-confidence and trap Lone in fear, anger, and a feeling of alienation towards her husband. She escapes to a university degree and thereby also to self-expression, to books and writing, and perhaps also to a life as an artist. The opposition between the mental imprisonment, which is emphasised by a distant relationship to a closed or unsympathetic husband, and the dream of self-expression continues as a theme in Korsangeren og andre noveller (1988; The Choir Singer and Other Stories) and Dukkenat (1992; Doll Night).

Frantic Freedom

“We can have moments ofcrazyfreedom. And we couldn’t really have them if we weren’t also confined,” says Jytte Borberg (1917-2007) in a 1984 comment on a collection of her texts, Hvad tænkte egentlig kaninen (What Was the Rabbit Actually Thinking), which has freedom as its theme. Properly speaking, all her texts take freedom as their theme.

Since her – late – debut with the collection Vindebroen (The Drawbridge) in 1968, Jytte Borberg has written about freedom, fantasy, and warping, about oppression’s inner and outer forms, and she has done so in literary forms that have moved between the fantastic and the realistic, between stylised and detailed and historical accounts. In her early works, it is possible to discern inspiration from abstract and fantastic modernism, and later there is a clear fellowship with the youth, student, and women’s revolts against authority and patriarchy, and the lunatics’ revolt against the norms for experiences and behaviour, such as in Slaraffenland (1982; Cockaigne). However, Jytte Borberg weaves them together in an entirely distinctive cultural criticism that has its own standpoint in the combination of a lived adult life with threads back to World War II and earlier, and a special affiliation with the modes of rebellion of later decades.

It is characteristic that Jytte Borberg retained her emphasis on the fantastic, art, the erotic, and the physical throughout the 80s and the early 90s. In the special ways women, the mentally ill, artists, and lovers experience and sense the world, she finds porous and unconscious flows of energy, a floating place between body and soul for which there is no room within the systems of power and normality.

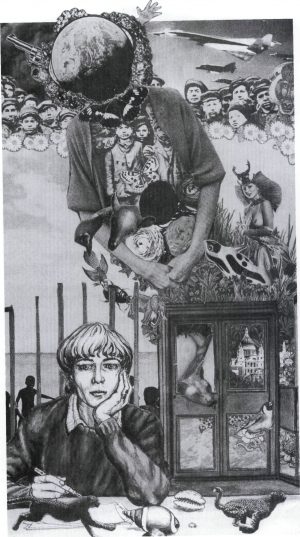

Arentz, Anne: Kvinden uden land, 1975. Drawing. The Women’s Exhibition at Charlottenborg, 1975. Exhibition catalogue

It is already a crazy project the main character of the same name in Orange (1972) takes on when she leaves her (banker) husband to become independent and free. Orange goes on a tour de force of Danish society’s models for unfreedom, in which she openly offers any service from washing floors to sex in exchange for a flat. It is both a grotesque and a realistic story about the living conditions in a society where everything – work, housing, love, friends – is part of a system of exchange that the main character happily accepts. The 1970s criticism of capital is at stake here, as is Jytte Borberg’s diagnosis of unfreedom as a lack of awareness about the coercion to which activities are subjected, and as an endeavour the object of which is measured in profit, where no one gives anything without getting at least the corresponding value in return.

Orange and the women in Turné (1974; Tour) can be viewed as Jytte Borberg’s contribution to 70s feminist literature. In 1976, she achieved great success with her historical tale about a servant girl in Eline Bessers læretid (Eline Besser’s Apprenticeship), followed by Det bedste og det værste – Eline Besser til det sidste (1977; The Best and the Worst – Eline Besser to the End). Eline, like other of Borberg’s heroines, has an appetite for sensuality and independence, and she pays to retain her own identity outside marriage and politics. The novels are based on the political and literary messages of the women’s movement, while still finding their own path. During her “apprenticeship” as a fifteen-year-old servant girl at the turn of the twentieth century, Eline has her consciousness very much raised. The novel listens to all the voices that seek to form and instruct Eline, and is full of irony towards the learning of the privileged classes and growing sympathy for the cook’s socialist class consciousness. In Jytte Borberg’s work, consciousness-raising is primarily a question of honesty and integrity in one’s personal life. A common pattern throughout her body of work is the impossibility of being integrated in – being one with – a normal life in society while at the same time staying true to oneself. A person is or becomes both wilful and demented when she insists on her own experience of the world. In this way, the desire for freedom also poses its own dangers.

In Jytte Borberg’s Rapport fra havbunden (1978; Report from the Bottom of the Sea), the young Agnete finds release when she sees the reflection of her sufferings in an old man’s figurehead, which is created, highly symbolically, in her director-husband’s boatbuilder’s yard as a wedge of resistance within the bastions of power.

Social – and anti-social

Before Jytte Borberg published her first book at the age of fifty-one, she had been a doctor’s wife for thirty years, with a husband working at a series of mental hospitals – a position that placed her, as a housewife, in the upper social circles, as well as involving her in her husband’s work and in the special nature of the hospital environment. She uses this knowledge in the novel Slaraffenland, in which the young main character, Iris, by virtue of her position as housekeeper and surrogate mother in the house of the chief physician is subjected in the extreme to the dialectic of madness. Iris represents normality, but also sensitivity, which is diagnosed by the good doctor as an illness requiring treatment. The mad society is outside, but also represents confinement in relation to the norm – provincial life in 1950s Denmark – which is described in glimpses as exceedingly prejudiced and narrow-minded.

Jytte Borberg describes fantasy, eroticism, childishness, and madness as types of freedom and also as social conventions. However, the conditions for upholding them come at a price. In her Tvivlsomme erindringer (1990; Questionable Memoirs), the narrator has become at least as crazy as Orange did twenty years earlier. In the language of surrealism and dreams, she tells her life’s story, but from the very beginning disrupts the common notions of the passage of life. She has a special view of time itself – in life and in the story:“Time is like a labyrinth, and the world is a flow of places that are closely tied together by people’s consciousness and awareness, by people’s search for happiness and peace and freedom”. In the story, she takes the image of the labyrinth literally through her constant breaks with narrative progression. The movement in time, which is normally understood as a movement in a specific direction, is broken up so that time itself becomes spatial, is given an extra dimension. This kaleidoscopic form of recollection is not unknown in the memoir genre; however, Jytte Borberg makes an extra point of it in her consistent use of dream techniques: the adult narrator can suddenly step back into her childhood home, where she meets an old boyfriend whom the father encourages her to sleep with. The dream departs from the everyday notions of time, space, and people.

Jytte Borberg’s Tvivlsomme erindringer (1990; Questionable Memoirs) are filled with animals as symbols of sexual instinct and reminders of the animal in people. There are tigers that turn out to be harmless, especially if you are not afraid of them. In several scenes, women appear with suckling pigs. In contrast to her mother, the narrator is fascinated by the smell of goats, the most rank of all animal smells, and has intercourse with a goatherd. Like animals, women carry their young in their mouths. And all these peculiar events are mingled with recognisable scenes. The narrator is minding her great grandchild who has a cold when a woman appears carrying her child in her mouth, a child she later swallows with a mouthful of red wine. The effect is that the recognisable and realistic also becomes – questionable.

Of course, the aim of this dream-like and surrealist technique is not only to characterise the narrator’s madness: from Orange onwards, convention, especially, is depicted as crazy. However, Jytte Borberg by no means views her linguistic fantasy, her breaks with the proper law and order of reason, as an immediate solution or release: “Many people actually believe that you can free yourself from your own problems through writing. I find, to the contrary, that I write in order to come into contact with them,” she says in an interview.

In Jytte Borberg’s universe, the special balancing act between power and madness does, however, have a stabilising point in art. In art the visions, the senses, and the breaks with the norm become socially acceptable, but art also becomes the place that releases those who are struggling, because the artistic images have their root in the unconscious language that is, again, the language of the senses, the impulses, which have their own laws. In the images, we recognise the forgotten and the repressed. How the artistic process works becomes clear in both the content and form of the narratives. The artist Lotte in Sjælen er gul (1981; The Soul is Yellow) finds the strength to preserve her visions as artistic and valid when she comes into contact with the dead painter Olivia Holm-Møller (1875-1970) while taking classes at a folk high school. The text takes Lotte’s experiences literally and brings her fantasies to life in a surrealistic style of writing that acknowledges the dialogues with Olivia on the colour of the soul. Lotte’s goal is to insist on herself and on her own sensations. In the artistic dimension it is possible – and lonely: “The white is my loneliness / my good loneliness”, says Olivia in a poem in which she uses the egg as a metaphor for her own world.

Loneliness also becomes a condition with respect to erotic relationships: Jytte Borberg’s texts are filled with descriptions of relationships based on powerlessness, oppression, and bartered deals, while at the same time, sensuality and eroticism pervade the language and, especially, the women in the stories. The path of desire also appears, out of necessity, to move outside the social conventions: Iris loves an involuntarily committed patricidal patient, and in Løslad kaptajnen (1992; Release the Captain), the erotic, anarchistic, and anti-social elements of the unfaithful husband and defrauder, who lives with his maid, are highly valued. However, there is still a dialectic insistence on the costs – madness and death.

Life and Writing

“As long as we live in a time where it is still necessary to explain why the lack of insight in the self delays development – I can’t see how we can live without the function of the small-talk group for both sexes, or the personal narratives that teach us all something about ourselves,” wrote Bente Clod (born 1946) in the Danish daily Information in February 1978 in defence of “the personal narrative”, including her own novel Brud (1977; Break), a tale about “Bente Clod” and her personal process of self-realisation in love and work. The genre is the confessional novel: the personal life with its secrets serves as a pattern for everyone’s secrets.

In Pil Dahlerup’s review of Brud (Break) in Information on 26 May 1977, she distinguishes between Bente Clod and “Bente Clod”, but in both she sees a danger in allowing the personal to be the measure for everything: it “can reduce the entire third world to a personal matter,” and it can lead to the establishment of “such unconditional demands on the mental presence of others that it invariably leads to a breakdown”. The problem, she says, is that the deserving occupation with the personal traps the author and the heroine in the clutches of narcissism, a trap “which not only belongs to her, but also to the women’s movement and to other revolutionary movements”.

Writing and public life had a special importance for women. It became an insistence on women’s competence when it comes to understanding their own lives and needs, and it became an insistence on stories in which the female ‘I’ is a topic of interest. At the same time, the emergence of the female ‘I’ in the language led to a change in the importance of being ‘I’ – and woman.

Brud became famous and infamous – and was read and discussed throughout the Nordic countries. In form, it disposes of the distinctions between author, narrator, and protagonist – they are all called “Bente Clod”. In content, it rejected every pattern for accommodation between the individual and the social order. The title signifies that it is about breaking on many levels. The theme is clear in the novel’s love story, which proceeds via a chain of break-ups and reconciliations until the final break. However, the break between the lovers is also the ‘I’ narrator’s break with her old identity: her dependence on being in love with a man. She becomes a lesbian, and discovers writing and expressing herself in public as a means to independence: the ‘I’ has gained in importance as the conclusion to a therapeutic, artistic, and political process.

Truth or Dare

Brud is the story of the journey from a weak to a strong female identity. However, the confessions also question where women’s true identity really is in the midst of the jumble of roles, emotions, experiences, and language.

Den frygtelige sandhed – en brugsbog om kvinder og masokisme (1974; Eng. tr. A Taste for Pain – On Masochism and Female Sexuality), by Maria Marcus (born 1926), put this issue into sharp relief. It was a piece of confessional literature about a female desire for suffering and oppression – rather than liberation and power. It was also a genre-mixing handbook that could be used in many ways. It was pornographic, it shared a number of experiences, and it reviewed and discussed classic theories about masochism. The book – and her entire body of work – takes a special approach to the objective of literature of experience, especially with regard to the questions about the relationship between language and truth, femininity and nature, emotions and politics. In 1964, Maria Marcus published Kvindespejlet (Woman’s Mirror), a satirical novel about the nature of femininity, written in the form of a diary. A special point of the novel is the way it contradicts itself because the female narrator considers writing a book to be unwomanly. Kvindespejlet is about femininity as a self-created, self-destructive, claustrophobic universe, a fantasy where the woman finds herself as a woman while at the same time suppressing herself as an individual. She creates a female virtue consisting of passiveness, submission, and silence. In order to realise the fantasy, she must reject the men who do not live up to the role as co-creators of the image of womanliness and manliness. But where do the fantasies and ideology come from? Is it the woman, herself, who brings about her own destruction?

Maria Marcus was born in Germany in 1926, the daughter of two non-orthodox Jewish parents who fled to Denmark with their children in 1933 and then on to Sweden in 1943. In a paradoxical and uneasy relationship with the obsessive fantasies of sexual masochism, she attempts in her memoirs to break away from the view of the self as just a victim and product of certain (biological) conditions, such as race. The Jews, she says, are not a race; what they share is a common culture. Is it possible to say the same about sexuality and its relationship to gender? The self is fate, on the run, instinctive, but the self is also heterogeneous, decided by diversity, searching.

In 1980, Maria Marcus picked up this line of thought in the novel Jeg elsker det (I Love It), which she co-wrote with Stig Sohlenberg. In it, she emphasises that the dream of self-effacement is a figment of the imagination, and can only be legitimised as such. The novel describes the growth process in a sadomasochistic relationship that realises the innermost dreams of both parties by alternating between the woman’s and the man’s point of view. Maria Marcus tries to save herself and feminism by differentiating between two truths: the truth about the sexual desires which are limited to fantasy, and the truth about the social and political desires which belong to the world of reality and revolt. But she also points out that language gets caught between the two projects. On the one hand, its aim is to represent truth (and in this regard, language belongs to the order of reality). On the other hand, the woman creates her own language and reality with her fantasy. There is a difference between fantasy and reality, reality and interpretation, but the difference is not static, it is in constant flux, and it becomes impossible to hold onto definitive conclusions. A pragmatic solution, of course, is therapy, which Maria Marcus depicts in Kys prinsen (1984; Kiss the Prince).

But if the personal experiences and needs of women cannot be an argument for liberation, then what can? Maria Marcus’ strategy becomes a division of labour between the political and the sexual. However, in the process, she also becomes a contradiction to the dream of the left wing and women’s movement of identity between the political and the private, life in the workplace, in politics, and in bed. Desire, politics, and femininity turn out to be three separate, yet collaborative, quantities, although it is not possible to see where one ends and the next begins. Even in Maria Marcus’ work.

In the memoirs Barn af min tid (1987; Child of My Time), and in the novel Lili-og-Jimi (1991; Lili-and-Jimi), about a sixty-year-old woman’s attempts to preserve her – erotic – life as a woman, the question of the split self is presented in a new light.

Post festum

Autumn 1978. The journalist Joan Jensen arrives in incognito at the remains of a women’s collective: a cold, miserable smallholding run by two women who live disciplined and shabby lives as the last vestiges of the great utopia of the women’s movement: the community of sisters.

This takes place in Ulla Dahlerup’s (born 1942) Søstrene (1979; Sisters), which describes the Danish women’s movement, here called the Thitites

As early as the mid-1960s, Ulla Dahlerup caused a sensation when she made herself a spokeswoman for diaphragms, even for very young girls. In the early Redstocking days, she participated in an action in which women would only pay a price for their bus ticket corresponding to their lower pay level. In 1962 she had made her debut with the novel Jagt efter vinden (Chasing the Wind), but after her early career as a writer of fiction, she mostly worked as a journalist, with a broad and often controversial involvement in social issues.

, and its development. The story is both tender and critical, a dual tale viewed from the inside and the outside, and thus mirroring Ulla Dahlerup’s own ambiguous position in the women’s movement.

The women’s movement and the left-wing political and sexual conflicts are also points of reference for Suzanne Giese’s novel Brændende kærlighed (1984; Burning Love). The importance of independence and freedom for a female identity is the theme of her later novels. In Forsvindingspunktet (1993; Vanishing Point), the first-person narrator thinks and writes about the intoxicating sense of freedom after 1968, when she, as a young girl in love, goes into shock after meeting two men’s – the father’s and the son’s – desires to have her as a lover. Ingrid in Den tredje kvinde (1994; The Third Woman) escapes from a boring marriage and hides behind the identity of a dead girlfriend. Slowly the true story of the friends unfolds as Ingrid, in a break from her life of conformity, makes a living as a belly dancer and begins to work as a photographer. The artist’s life and autonomy forms the new basis for an identity that also builds on the true story of the women’s lives.

The Redstockings and the women’s movement became literary material post festum. In 1978, Suzanne Giese (born 1946) published her debut novel På andre tanker (Change of Heart) and in 1980 came Bente Clod’s Syv Sind (Doubt), which includes a utopia about a women’s island which Bente Clod elaborated on in Vent til du hører mig le (1983; Wait Until You Hear Me Laugh). Ulla Dahlerup’s novel is the only one she published after her career as a young writer in the 1960s, while Suzanne Giese embarks at this time on a literary career after many years of writing practical, journalistic pieces in support of the women’s movement, including Hun (1970; She) – in collaboration with Tine Schmedes – and Derfor kvindekamp (1973; The Women’s Struggle – That’s Why). The points of view in the three stories vary. Syv Sind differs from the others in that it was written from within a living movement and with the utopia intact, while Søstrene was written for the dead. Here the women’s collective is the source of creative energy, while the works of Suzanne Giese and Ulla Dahlerup from the same period focus on the great passion and the big question. They all wonder about the meaning of the female gender, which in the 1970s became such a powerful force in literature and social movements. And in this way, they mark the start of a period in which the women’s movement has lost its innocence.

They recall the elation and the festive atmosphere which filled the women’s community. The core of that elation is the female gender itself, which acquires value and importance with the removal of all imposed norms. In Ulla Dahlerup’s novel, the sisters bathe together and symbolically burn all roll-ons and bras. In Bente Clod’s book, the women’s group Syv Sind publishes a book of photos of their own vaginas. Completely naked and under the skin, a gender comes to light and acquires meaning in itself.

Bente Clod and Ulla Dahlerup also highlight the conflicts in handling the liberated gender. Gender acquires meaning because the individual woman has become valuable as she is. However, the women’s collective also has a tendency to make all women identical, to anonymise, to de-sexualise – and to de-aestheticise the female gender. Thus, Bente Clod’s heroine, Mirjam, who is a well-known author, feels pushed out of the community by the animosity and jealousy of the others – but is ultimately accepted by the group, which is now interpreted as a life-saver of solidarity.

The fanatical Thitites in Ulla Dahlerup’s book also have difficulty accepting the sexuality and individuality that two of the members emit. Self-portrayal, desire, and beauty become, in her work, taboo within the movement. The intoxicating, inspirational development in the women’s community is replaced by a narrow-minded discipline and intolerance.

Søstrene is an ambivalent story. With provocative acuteness, Ulla Dahlerup reveals the blind spots in the ideology of the women’s movement. However, at the moment of defeat, when she has written the death of the movement, she has her Joan call the women together to support the last vestiges of their dream. In this way, the terminal point of the novel becomes misery as well as an insistence on never forgetting history.

Both Bente Clod and Vibeke Vasbo have been active in the Danish lesbian movement, which broke off from the women’s movement in 1974. The relationship between the heterosexual and the lesbian Redstockings was complex and characterised by suspicion. The lesbian women interpreted their love as a political choice and a sign of female self-sufficiency that makes men unnecessary.

Woman – woman

In 1976 Vibeke Vasbo (born 1944) published Al den løgn om kvinders svaghed (All the Lies About the Weakness of Women), which resolutely challenges all talk about accepted notions of femininity. The ‘I’ narrator in this documentary-style diary novel moves to Oslo where she finds work as a crane operator. The background is a love affair with a Norwegian woman; however, the private relationship is consistently pushed to the back by work-related and political conflicts, in a constant refusal to deal with or depict anything traditionally feminine. The story also becomes a document on femininity in exile. The narrator, Vibeke, is far removed from the political and cultural solidarity in Denmark, and finds the Norwegian left-wing community extremely patriarchal. And yet, in all its anger, the text also becomes an exile from the patriarchy – and from a specific notion of femininity.

In contrast, femininity is again given contours in the collection of poetry Måske har jeg haft en anelse (1980; I Might Have Had an Inkling), which moves from the theme of oppression through falling in love and takes a step further towards the new state of the ‘I’. Here, womanly love becomes the ‘I’s opening of body and senses. She is moved when she sees the woman she loves:

“My palms / the insides of my arms / the insides of my thighs / my chest and stomach / turn towards you / follow your movements / like the petals of flowers / follow the light”, reads the poem »Som blomsternes blade« (Like the Petals of Flowers).

After Danish writer Thit Jensen. See article “Twentieth-Century Woman”.

The poems about male society are epic, but in the love poems, the ‘I’ becomes lyrical, intoxicated, and open. She is not afraid to let her guard down.

In Miraklet i Amalfi (1984; The Miracle in Amalfi), Vibeke Vasbo wonderingly moves away from universality: “Once I thought everyone saw the same thing – they just wouldn’t admit it. But that’s not how it was. In fact, my sight became more and more remarkable day by day”. While Al den løgn om kvinders svaghed was a truth text where the ‘I’s outlook on the world sought to convince others, the point of departure is now an openness to the world’s remarkability. In the story, the ‘I’ opens herself to the miracle of love; on a study sojourn in San Cataldo she falls in love with a Danish priest, and under the sun of the Catholic south, a number of interpretations of outlook and body are eroded, adding surrealistic images to the text as signs that the world can take on shapes and contain meaning beyond the normal good sense of a Danish woman. The meeting with love requires a new interpretation of gender, and the Christian concept of loving thy neighbour steps in as a mediator leading to the notion that the opposite sex can be relevant. In this chaos of new outlooks on the world, the female aesthetic also changes, addressing ambivalences in the dual-gendered world.

In Hildas sang. Historisk roman fra 600-tallets England (1991; Hilda’s Song – A Historical Novel from 7th Century England), Vibeke Vasbo writes about the correlation between love and Christianity – and about aggression and oppression as part of the history of Europe, the Church, and the sexes.

The novel is a distinctive combination of detailed historical studies and free invention. The historical sources tell very little about the life of the Abbess Hilda before she entered the convent; Vibeke Vasbo invented her entire love life, her children, and not least her marriage with the un-baptised Penda. In many ways, Hilda is a modern woman, divided between the Christian message and her own motives of revenge, and open to modern science. Christianity is understood as part of a civilising process in which the message of love will put an end to vendettas and wars and abolish human sacrifices. However, the Roman Catholic Church institutionalises itself as an increasingly centralised power that seeks to make the education of the nuns a lower priority, that is, it wants earthly power, while Hilda and the novel emphasise love – also bodily love. The love and woman’s message pervades the order of nuns, where Hilda forgives a lesbian couple (as long as they stay away from each other) and fights for women’s right to education and positions of power.

In the gospel of love, the Amalfi book is followed up on, the struggle between the two sexes as natural enemies and neighbours, and potential lovers, is played out against the backdrop of history. It becomes a theme for the civilising process of Western culture as a constant conflict between life/desire and death/hate.

Another motif – the artist’s motif – appears at the end, when Hilda finds a poem written by two nuns that expresses Hilda’s sorrow over the death of one of her sons: “It is strangely liberating to say the words out loud”. It is this universal artists’ psychology that the activists and artists of the women’s movement turned into such a central aspect of their aesthetic.

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd