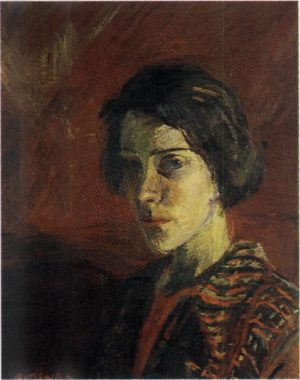

Súsanna Helena Patursson (1864-1916) came from a family of copyhold farmers. Her family owned the largest farm in the Faroe Islands. When she was a young woman she moved to Copenhagen to get an education and she found employment as a legal secretary. Her struggle for women to be allowed access to the Faroese nationalist movement’s meetings became a family matter. Two of her brothers, Sverre and Jóannes Patursson, were leading figures in the movement; her activities were a female counterpart to Jóannes’s political work. He spoke to men about national consciousness: about promoting their language and culture, about self-assurance and national pride. Súsanna Helena Patursson spoke to women, encouraged them to participate in the public discussion forum, to get an education, and she instructed them as to how house and home should be organised. She edited and published the first Faroese women’s magazine, Oyggjarnar (1905-08; The Islands), making housekeeping, interior design, and cooking recipes a national and political issue. She returned to the Faroe Islands in 1904, and became secretary of a local discussion club, a kind of preparatory forum for the national Føringafelag (The Faroese Association). One of the aims of this discussion club was to teach women the ropes of public administration, and to this end men and women took it in turns to fill the roles of chairperson and keeper of the minutes at the meetings.

Súsanna Helena Patursson wrote the first Faroese theatre play, Veðurføst (Layover Because of Bad Weather). It was performed in 1889, shortly after Føringafelag had been set up.

As a consequence of a Danish Act of 23 March 1852, the Faroese Lagting, (Faroe Islands Parliament), having been abolished in 1816, was re-constituted and the Faroese were to send two representatives to the Folketing (Danish Parliament). That same year an attempt was made to create a forum for political debate: the first daily newspaper, Færingetidende, published by the lawyer Niels Winther, a Member of Parliament from 1851 to 1856. The project failed. The first viable newspaper was not launched until 1877: Dimmalætting (Dawn), which is still the largest newspaper in the Faroe Islands. Føringafelag (The Faroese Association) started production of Faroese periodicals; in connection with the movement in Copenhagen, two poetry anthologies were published: Føriskar vysur (1892; Faroese Songs) and Sálmar og sangir (1898; Hymns and Songs). Both included work by Billa Hansen.

The original manuscript for Veðurføst has been lost, and there is no extant copy of the whole play. All we have today are single copies of four of the in all twelve roles. They show Veðurføst to have been an everyday tale with ‘scenes from folk life’. The storyline cannot be reconstructed, but the extant fragments address some of the big topics of the day: misuse of alcohol, nationalism, and in particular, women’s attitude to both.

At the end of the nineteenth century very few people could write Faroese. In the 1840s, V. U. Hammershaimb (1819-1909) worked out a Faroese orthographic system, which came into use at the very end of the century; it was not made an obligatory school subject until much later, and right up until 1937 it was compulsory to use Danish in schools. From its inception, the national movement and Føringafelag put the development of the Faroese language and respect for Faroese culture at the top of its agenda.

The Faroese national movement was formed in 1876 by students living in Copenhagen. In 1888 the movement got a foothold in the Faroe Islands themselves with the setting up of Føringafelag (The Faroese Association). Until the mid-1800s the Faroe Islands had been a farming community, without institutions such as publishing houses and news press. This changed in the second half of the nineteenth century with the first newspapers and book publications. A modern Faroese literature and an evocative, nationalist-minded poetry, which were not a direct continuation of the oral tradition, grew out of the national movement.

Generally, women were the last ones to learn how to write Faroese, but Veðurføst shows how those who were interested arranged to learn writing skills in groups taught by, for example, the local teacher – if, that is, he was nationally minded.

Besides Veðurføst, the first theatre evening under the auspices of Føringafelag included a production of Gunnar Havreki by Rasmus Effersøe (1857-1916). Gunnar Havreki is a Romantic play about male strength, female sensitivity, and fidelity; it has survived in its entirety. In a 1925 article about Faroese theatre, Christian Holm-Isaksen writes: “While the audience sat and roared with laughter at the comedy of Veðurføst, weak women swooned when Gunnar Havreki perished pitifully in darkness and sea-storm on stage. Where the first play was tame and uneventful, the second was intense and exciting. Veðurføst, a pleasant and gentle picture of everyday Faroese domestic life, in which much is said, has the usual plot with two young people finding one another.” (Varðin, periodical, 1925; The Cairn).

The reviewer clearly prefers Gunnar Havreki, even though he considers it a somewhat melodramatic affair.

Both plays were popular and were performed to a full house four times – what is more, the run gave a profit. Staging original plays in Faroese so quickly after the setting up of Føringafelag was a palpable victory.

Súsanna Helena Patursson’s attempt to make her name as an artist in the Faroese public eye nonetheless failed. Her plays did not survive. The roles in Veðurføst were copied out individually, distributed between the actors, and thus lost. Her women’s magazine was not well supported; it was ridiculed both within and outside her own circle – that is to say, also by the nationalists and the folk high school milieu.

Súsanna Helena Patursson’s poem “Far væl” (Farewell) describes the feelings of a woman betrayed by her beloved – he has found another. But the poetic speaker has not lost her self-esteem. Parting is bitter-sweet, she wishes him every happiness, but also puts the blame at his door. The poem can be interpreted as a definitive good-bye to love and as an account of the price paid for female independence.

But, go now, farewell

God bless you all your days

may He bless you all along your way

be good to her and forget me

I will mourn myself to death so tired

of grief

I was too good for you.

On the other hand, a compilation of her recipes and her housekeeping advice from the magazine were later published.

Súsanna Helena Patursson also left two short stories written in Danish, which were presumably not published. “Han duede ikke” (He Was No Good) and “Helga og Oluf Weller” (Helga and Oluf Weller). Both deal with the contrast between love and marriage. The central female characters are deeply in love with the ‘wrong’ men, who try to take the easy route to money and power. The women themselves are veritable paragons of virtue – hard-working and with a sense of justice that insists on revenge. In “Helga og Oluf Weller”, Helga marries and has children with a man who holds no fascination for her; he is not described in anything like the same detail as Oluf – the man she loves, but who lets her down. The tale bears similarities to the author’s own unhappy love story.

Homelessness

While Súsanna Helena Patursson’s writing was thematically on the threshold to a new departure, the poetic speaker in Billa Hansen’s (1864-1951) poems is homeless.

Billa Hansen lived alone and worked as a teacher in Brønshøj, a Copenhagen suburb. She had left the Faroe Islands, never to return. Her work describes loss of the childhood land in existential terms, not, as in the writing of some of her contemporaries, in terms of nationalism and celebration of the homeland.

She has not left a very large body of works – just eight poems, which appeared in the first Faroese songbooks and in Várskot (1898-99; Spring Sprouting), the Faroese journal published in Copenhagen. One of her poems has remained in Songbók Føroya fólk (The Faroese People’s Songbook), seventh edition, 1976; it is a text about the perils of the ocean – a theme that was deemed acceptable for the pens of writing women.

Some of Billa Hansen’s poems are strikingly different from the rest of Faroese poetry at the time, which was mostly a case of patriotic songs, most often written for special occasions in the Faroese associations. The closest Billa Hansen gets to this tradition is the poem “Ain skægvarfer” (A Picnic) in Føriskar vysur (1892; Faroese Songs), about a Midsummer outing to Dyrehaven, a forest park north of Copenhagen. The poem depicts gentle Danish nature in contrast to its harsh Faroese counterpart, but it is completely devoid of homesickness. On the other hand, the poem criticises conditions of life abroad in the account of the contrast between work, which is hard and demanding, and amusement, which is hard to come by. The poet defies all obstacles and goes on an outing. She is more than happy to tackle the punch bowl, but she resolutely shuts her mind to the sexual sensuality represented by a Midsummer witch. By not focusing on sexual attraction between the sexes, “Ain skægvarfer” rejects the image of woman that dominates the rest of the patriotic poetry. The de-sexualisation is elaborated on in her later poems, which describe loneliness, particularly the lonely woman’s psychological distress in modern society. She sometimes uses free verse and writes prose poems, which was unusual in Faroese poetry at the time.

Ja, fryhait live hökt hænda då,

o adlar trödlkonur liggje tit haima!

tit tryvast so idla y kátun lä,

mæn fejin kjá manne á kådda- nun dråima;

til Blåksbjörg tit rænne,

og här tit brænne

til tæss ät svart verur tikkara ænne,

y smildur fer!

y smildur fer!

(Yes, freedom long live this day,

and every witch, stay in bed!

You thrive so poorly in playful company,

but are happy to dream on man’s pillow;

to Brocken you run,

and there you burn,

so black be your skull

and smashed to pieces!

smashed to pieces!)

Billa Hansen: “Ain skægvarfer” in Føriskar vysur (1892; Faroese Songs)

The poem is written in a phonetic orthography constructed by Jakob Jakobsen (1864-1918). There was a bitter dispute in Føringafelag about the two written languages. Hammershaimb’s orthography based on etymological principles won, and is largely the system still in use today.

Need, longing for death, and repression are key themes in Billa Hansen’s poems. They were allowed to slip out of the history and teaching of Faroese literature. The leading male figures in the national association disagreed about the consequences of developments in modern society and culture, and later on only the optimistic attitude and opinions were remembered. The period around the turn of the nineteenth-twentieth century is still considered to be the great revivalist time, a period in which all modern development – cultural and industrial – kicked off. Billa Hansen was not deemed acceptable in this context. Posterity has not registered women’s major role in securing material advances, nor their cultural contribution during the time of upheaval. Women were not making the political decisions, and their empirical world created other pictures.

By Choice

Andrea Reinert (1894-1941) went to Copenhagen in the 1920s. In the poem “Fráfaring” (1932; Departure) the narrator not only leaves the Faroe Islands, she also leaves a ‘you’, standing on the beach waving. The sea metaphors symbolise the poetic speaker’s fear on parting, fear that this kind of voyage might take her way out of her depth. But the waves help her leave, and when she gets out where “bylgjurnar leika i trá” (the waves play in longing), she forgets the figure on the beach. The poet is compelled to set forth by a longing for social and intellectual freedom. While the poetic speakers in Súsanna Helena Patursson’s and Billa Hansen’s poems were left on their own, Andrea Reinert’s poetic speaker bids farewell to love of her own accord. The departure in Andrea Reinert’s account is one of choice.

Her awareness of death is also different to that of Súsanna Helena Patursson and Billa Hansen. A poem she wrote when she was young, “Duldur eldur i barmi inni” (Hidden Fire in My Breast), has an ‘I’ who is almost consumed by fire and who frantically longs for a ‘you’ – this ‘you’, on the other hand, is cold as ash. Life is made of fire and longing. It ends when longing is forgotten.

The Midwife of Faroese Literature

Maria Rebekka Mikkelsen (1877-1956) was a key figure in Faroese culture. She lived in Copenhagen, where she was very active in the Faroese milieu. She welcomed and helped the young men who came down to study, and she helped all the Faroese writers of the period: procured printing blocks, fetched and returned proof sheets, and often did the proofreading, too. She was the midwife of Faroese literature in the first half of the twentieth century.

Her writing, meanwhile, show other facets of her talents. “Fyri fyrst” (1945; So Far) is a short story – perhaps a fragment of a novel that was never finished. The main character is a young man living alone with his mother in a milieu where sexuality is suppressed. Sexual intercourse and children born out of wedlock are synonymous with social calamity. The women around him warn against making himself guilty of that kind of thing. And therefore he loses the young woman he loves. His temporary salvation is the masculine fellowship aboard a fishing vessel, Refuge. The vessel is compared with a woman – with whom he can huddle up and fall asleep. Desire is deferred, and the women’s agenda with the young man succeeds.

In “Fyri fyrst” there is a close feeling of common cause among the women in the young man’s family. The women are alone with their children, and the men who turn up just give them problems: one woman in the family twice gets pregnant with men who let her down. The young man’s mother is a widow, as is his aunt and their friends. The strong sense of female solidarity prevents the young man from developing into a real man, until one of his late father’s skipper friends notices that he has an ‘effeminate’ job looking after the office and stockroom for a ship owner. Arrangements are made so that he can join the skipper’s ship – and there he can embark on his masculine development.

The composition of the story is that of a Bildungsroman. The boy is at home; then he leaves and voyages forth, a fisherman. Home on a brief visit, he tests out some of the things he has learnt; by the time he goes away again he has reached a new stage in his development. The narrative style is impressionist, and this makes the story unique in Faroese literature: it jumps freely between outer and inner worlds, between thoughts and description, between free indirect style, direct speech, and narrative. The text is full of pauses, interrupting the narrative and allowing or demanding the reader’s active co-creation of the story.

“Self-criticism can be good, but Maria, you have always been too hard on yourself, both with regard to what you have said and what you have written, it comes so easily to you, the dialogue is so easy and natural and pithy and the content of value. – One derives benefit from hearing and reading you,” writes Billa Hansen in a letter dated 12 March 1947 to Maria Mikkelsen. The letter is written in Danish and possibly refers to the short story “Fyri fyrst” (1945; So Far).

The older male poets did not give an account of what they got out of journeying abroad. Maria Mikkelsen does. In “Tjaldurunga beyð hin lagna harða” (The Hard Fate Bade the Young Oystercatcher to Leave), the poet identifies with the young oystercatcher forced by the harshness of its life to leave its home – the migratory oystercatcher is the national bird of the Faroe Islands. Abroad, the youngster learns new languages and customs, but at the same time keeps and safeguards its native language. The poem represents Maria Mikkelsen’s own story, and it gives a picture of how life turns out for those Faroese who leave their homeland in order to pursue further education.

Súsanna Helena Patursson, Billa Hansen, Andrea Reinert, and Maria Mikkelsen were more interested in ‘abroad’ than were their contemporary male poets. More often than not the men write about home and, in particular, homesickness. The women do not seem attached to the homeland in the same way. As far as Billa Hansen and Andrea Reinert are concerned, home is a part of their make-up from which they each in her way try to break free.

Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen’s Scenes of Folk Life

“Once upon a time there was a young, beautiful girl; she was engaged to a man who was studying to be a clergyman. Once he had finished his training, he wanted to get married. Now she got apprehensive, because she was afraid to have children. She did not tell him, however.”

In “Gomul søga” (Old Story) by Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen (1877-1974) the young woman asks for help from an old woman who tells her to turn the grinding mill three times round the wrong way. The number of beats she hears will be the number of children she will not have to bear. She marries; the couple remain childless. Many years later, her clergyman husband finds out that she is bewitched – she has no shadow. She tells him everything, and he punishes her by locking her inside the church for three nights. While she is in the church, three unborn children visit her. Had they been given life, two of them could have become men of importance; but the third child would have been a girl, and she would have been disabled. The two sons reproach their mother for her action, whereas the girl consoles her and says that it was a good thing she was not born. When the clergyman learns of this, he curses his wife and she dies. But roses and lilies grow out of her shoes.

The story is characteristic of Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen’s writing. Her stories about women in the old rural communities describe transitional phases in women’s lives – the changes from child to adult, from unmarried to married, and widowhood itself. Life between marriage and the husband’s death is usually left out. A few stories, such as “Gomul søga”, take place during married life – but then lack of motherhood is the subject of conflict – and all her stories take inspiration from myths and they all have the feel of folk-tale.

Returning Home

The point of view throughout Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen’s narrative universe is omniscient and external; the characters’ thoughts are but sparsely reported, and stories are also scenes of folk life. They have an educational feel, which corresponds to Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen’s statement that she wrote in order to preserve memory of the past. She also stated that her intention was not to revive olden times, but this wish lies implicitly just under the surface. Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen considered her writing to be beneficial for society, and it compensated for her secluded life. Her husband was a lighthouse keeper, and the family lived on remote headlands and islets far from the villages. This isolation and loneliness is a criterion for her ties to the past: the good old days, when everyone was part of a wider community, when a few strong authoritative figures held the reins of power, fortunes were either good or bad and everything was ultimately in the hands of God. Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen lived at a time of colossal change both in society as a whole and in day-to-day life. She herself had moved far from the rural community, she owned no land, she was married to a government official, she had eight children, but the nature she lived in was the same nature as it had been before.

The first women writers in the Faroe Islands wrote while they were young. Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen did not pick up her pen until all eight children had grown up and left home. Only then did she have time for such work. Her collected writings have been published in four volumes, Gamlar gøtur (1950-73; Old Paths), and include accounts of folk life, poems, translations, and stories.

“[…] my dear, let me receive a long letter from you. I will not ask, for I know that you have enough to write and to work on, but a husband and six children, soon seven (between you and me), you do not have. I am so angry, but as the girl said, it has come, so it must be thus […] it is hard work indeed, yet I can say with David that ‘The lines are fallen unto me in pleasant places’”, wrote Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen to Maria R. Mikkelsen in 1912.

In 1967, Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen received the Faroese literature award M. A. Jacobsens bókmentavirðisløn. That same year, she got her first desk – on her ninetieth birthday.

Her scenes of folk life are about life and work in days gone by. First, she wrote about men’s lives and work at sea and in the mountains; after that, she wrote pieces about women’s work. Unlike the prominence Súsanna Helena Patursson gave to housework in the women’s magazine Oyggjarnar, Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen points out that the daily domestic work was “húspjak” and “pjak” – that is, pottering about – which was earlier often left to the older girls. The mistress of the house took care of the real jobs – dyeing, making clothes, working with grain, and so on.

While Súsanna Helena Patursson, Billa Hansen, Andrea Reinert, and Maria Mikkelsen travelled out into the world in order to learn, get ideas and, not least, experience, Johanna Maria Skylv Hansen’s writing took her back to the old rural community.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch