“From my blissful seat in the corner of the carriage I could look out at the hated civilisation from which I would now be relieved for a while. There were smart railway assistants wearing important expressions and very tight, white pantaloons, there were young ladies wearing gaudy colours, gaudy hats, and gaudy merriment, there were elderly gentlemen with roses in their lapels, travel shoes, bright parasols, and an insatiable curiosity about people’s names and financial circumstances, – these were the worthy bureaucrats who reside in the country from six o’clock in the afternoon to nine o’clock in the morning.”

While Adda Ravnkilde’s heroines stepped hopefully onto the train of progress, Illa Christensen’s travellers, as here from her collection of stories, Skitser (1886; Sketches), are of a more blasé nature. He – for it is a man – ensconces himself as a passenger journeying through his surrounding world, sitting in comfortable anonymity behind the window whence he can observe the crowds.

In the sketch of the view across the platform, modernity is at large both as motif and as style. On the surface, we are given a classic, realistic description, but underneath there is a noisy gathering of fragments: important expressions, white pantaloons, gaudy colours, and gaudy shapes. An impressionistic style in which sense perception runs straight through the pen without apparently being sorted out and put into proportion by a marshalling consciousness. A text resonating with the pulsating life of the city.

The train as motif is a highly concrete and yet also highly symbolic expression of the city. Steam power and development of the infrastructure had opened up the world. Railway tracks gradually branched out across the entire country like an enormous nervous system, drew new lines in the landscape, connected parts of the country, countries, and turned the countryside into the hinterland of the city. Whether a train trip was taken in order to get away from or get to – the city came along too!

The city itself was the prerequisite for both the organised and the literary female public. It promoted the masculine outlook on the world – made it possible to describe and structure what had hitherto not been systematised – and the feminine outlook. The passive-visual, which had previously been a female approach restricted to the intimate sphere, captured the street scene. The shop window displays played on the visual aspect, and in the thronging, anonymous streets the surrounding world was turned into facade, sense impression. It was permissible to stare – for women too! Conversely, however, women were then stared at as well – by the merchandise, by one another, by men.

In his early journalism, Herman Bang developed an impressionistic style reflecting atomised city life, a ‘female’ sensibility that fictionalised the report and rendered the surface a multitude of sense perceptions. On 8 February 1880, in the newspaper Nationaltidende, he takes us along “I Modesalonen” (In the Fashion Salon):

“Emilie nods, shakes hands, and talks. Miss Hammer is consulted about a coat. The coats are hanging side by side in a long row: light and dark, dolmans and throwovers, long cloaks, velvet and furs. The semi-darkness in the shop tones down the colours of the materials, the meagre light congregates in a glinting gaily-coloured bead trimming on a velvet jacket. The light havana-brown gleams through the darker shades, the glow from a lit gas lamp lingers across a dark-blue velvet fold.”

Ibsen and the ‘claim of the ideal’ animated the modern women to leave the patriarchal home, just like Nora had done. But it was the climate of modernity in which they would materialise, in an urban landscape where market forces and unleashed sexuality had undermined the transparent relationship between cause and effect, between signifier and signified. A look had formerly ‘meant something’ – it could be assigned sincerity or duplicity, honest or dishonest intentions. The thousands of looks that now locked eyes on the street had no other intention than that of the moment. Sexual allusion was put into circulation amid anyone and anybody, and reality transformed itself into myriad eye-catching. The borderline between subject and object, maleness and femaleness, became fluid, and the imaginary ‘female’ existence became an omnipresent keystone of emancipation and progress.

Masculinisation versus feminisation – this was the divergent underlay to which the modern woman applied her pen! She wrote in order to ‘become somebody’. By expressing herself on the subject of ‘something’ she could leave her stamp on the world – she could come into being!

On the other hand, she came from an enclosed domain where she was unprepared for this ‘something’ no longer existing as such: the turbulence of city life had changed the perspective. The long stretch had given way to the sporadic, and personally delineated space had overflowed into a stream of derestricted reflections – in windowpanes and in eyes. In a sense it can thus be said that the female otherness, which the modern woman thought she had put behind her – in the very act of writing, by manifesting herself – now greeted her as the reality to which she must be attentive if she wanted to create art.

Added to this mental paradox was the social difficulty of ‘getting out of the house’ in the first place. The ramparts had indeed fallen and notice of freedom had been given, but this was mostly as ‘window dressing’. The money was kept where it had always been kept – in the man’s pocket. Men were the masters of the street, publishing, the newspapers, opinions. The women who would not settle for watching, but also wrote, therefore had to get things on credit: borrow the new books, borrow a hearing, borrow some room. They had to lean on male patrons as female admirers, as sisters, as wives.

Indoors, but nevertheless outside! Life on the periphery of the city flickers from the flurried pens of Modern Breakthrough women. With shrewdness, melancholy, or desperation they people their works with upstarts, idlers, coquettes, and those who are insane.

The Parvenu

Man skal altid (One Must Always) is the title of a guide to etiquette published by Emma Gad in 1886. A slim, little book that could be popped into a pocket – and then referred to surreptitiously should the parvenu get lost in the social conventions of bourgeois society. The marketability of this kind of book was a sign of the times. Expansion in the commercial sector brought swarms of upstarts in its wake.

Those women of the Modern Breakthrough who gained a hard-won seat at the literary and societal table were, in a way, upstarts in the community of men. There were no ‘catechisms’ available to these women, however – they had to find out for themselves how to hold their own in the outside world.

Some works by women featured the parvenu, either veiled behind other characteristics or – more rarely – exposed; but almost always the object of conspiratorial sympathy and fascination mixed with aversion. Frequently – as in works by Massi Bruhn and Adda Ravnkilde – the parvenu is a motif manifested in a series of misalliances. Ragnhild Goldschmidt presents this motif in a glow of irresolution: must one always?

In Use – But Not Instituted!

With her short novel En Kvindehistorie (Story of a Woman), Ragnhild Goldschmidt (1828-1890) wrote herself into the Modern Breakthrough in its early phase. The novel was published in 1875 and was thus a late debut work. It was also her only independent book, her other publications amounting to a total of two short stories serialised in the daily paper Fædrelandet (the Fatherland). Despite her relatively advanced years, Ragnhild Goldschmidt was an active member of Dansk Kvindesamfund (Danish Women’s Society), and her most valuable contribution to the women’s cause was in co-founding Kvindelig Læseforening (Women’s Reading Society) in 1872. From 1881 onwards, she ran the work of the reading society and thus did her share to provide women with a ballast of learning that did not have to be borrowed from men.

She herself remained, both as artist and as private individual, in the shadows. She spent her life with her brother, Meïr Aron Goldschmidt, until his death in 1887; and it was he who published En Kvindehistorie. One sign of Ragnhild Goldschmidt’s unease, and her lack of a fixed place in the new era of upheaval, is her anonymity; another is the character she allocates her first-person narrator in the novel. In a light but subdued style, Sofie tells the tragic story of her friend Laura. It is, however, not an omniscient narrator who interprets as she tells; on the contrary, Sofie is consistently left in ignorance about the power of the sexual forces steering her friend towards disaster: “[…] it was said that she was a coquette. I do not know if that was the case; I was so used to her that I could discern nothing.”

Laura is a true upstart with nothing but her sex to offer for sale on the marriage market. When she falls passionately in love with a married landowner, she thinks that her sexual and social fortune is made. But the landowner forsakes her, and in desperation Laura marries an ill-humoured farmer from the west of Jutland. Six years later Sofie is reunited with a dying Laura; now, for the first time, she intervenes actively in the story by bringing about a reconciliation between Laura and the landowner.

Like the stories told by Vilhelmine Zahle and Christine Mønster, Laura’s story – woman’s story – depicts a female passion that is in use, but not instituted: it has no social orientation.

The other woman’s story, which supports Laura’s, similarly deals with a sensitivity that is awakened, but never finds its form, a new departure that occurs at a remove, and an ‘I’ that lives a life as spectator to the lives of others. The both gentle and strict mother prevents Sofie from living a life that is her own by weaving her into a web of sympathy and suppression. She is not even allowed the upstart’s entitlement to suffer defeat, but has to stay in the role of observer – there where “the romance of life” passes by.

Female sensitivity in Ragnhild Goldschmidt’s En Kvindehistorie (1875; Story of a Woman) proves a hindrance to personal experience-based learning:

“And is it due to mother’s strictness, or because the romance of life has passed me by personally, that I have such great sympathy for the heartbreak of others? I do not know, but it is said that I am somewhat sensitive.”

This narrator is a portrait of the woman writer in the Modern Breakthrough who, having no personal experience, has to write from the experience of others. As an author, Ragnhild Goldschmidt is thus of a transitional type: she might indeed write from the parvenu’s sense of deficiency, but she is still writing from a predominantly Romantic vantage point.

A Son

Illa Christensen’s novel En Søn (1890; A Son) is a searching study of a parvenu. The central character, Olaf Holm, has never really grown up; he has ruthlessly cut himself off from everything that has any connection with his childhood, and yet he has remained – a son!

Olaf Holm is the prototype of a modern, upwardly-mobile careerist. He is the perpetually injured party, desperately aspiring to wrest himself free of his poor and illegitimate origins. He works, studies, grafts, gets the best of exam results, the best of jobs and, finally, a highly cultured wife – and he learns precisely nothing! He never steps up to his personal plate, never allows himself to settle into life, but settles for using it as his “reflection”, as “material for vanity”.

Marriage is a cultural clash reflecting, on the microcosmic level, the same slide in values as that which triggered controversies in the public forum. Olaf’s wife has a notion that marriage should be a “life together” and not just a get-together. She wants “personal worth” and therefore has expectations of a personality that Olaf has by no means developed. On the contrary, the marriage reveals the indolence that is the flipside of the parvenu’s acute tension. Having finally acquired the wife he desired, he no longer has the energy to make an effort – he is physically as well as mentally undressed – can neither be bothered to dress properly nor have a conversation with her.

The novel is a finely tuned psychological analysis of how a modern mindset undermines the Biedermeier culture from within. Not only Olaf, but also his wife, is the product of a modern doubt.

The modern issue of faith and doubt is also brought up in Illa Christensen’s En Søn (1890; A Son):

“ – but enslaved as he had become by his fate, he had only the worldly-wise doubt of the thrall, could not adhere to the enthusiastic faith of the free man.”

She is thus aware of all Olaf’s weaknesses when she marries him, but nonetheless follows her pure instinct:

“ […] but that I now in full consciousness cover eyes and ears, leave everything high and dry, and dive straight into the heaviest seas, because I cannot, no! will not, will not live without you, – then I also become fearful that I forsake something, but what that is I do not really know, – but – something that will possibly catch up with me – later in life, when my life is a part of yours.”

The high-flown drama is meanwhile gradually toned down to an everyday level. While Emma Gad used laughter to head off disaster, Illa Christensen uses subtlety to play the characters off against each other. None of them are ‘whole’ personalities, and their extremely tangled web of motives and motifs acts as a kind of common denominator. They have to live in an opaque daily round, and in their separate ways they come to terms with one another’s half-measures and weaknesses. Ambiguities thus adroitly turn a novel of decadence into a tale of personal development. Despite the similarities, there is therefore a world of difference between this novel and Olivia Levison’s depiction of a female parvenu’s fate.

A Daughter

Olivia Levison’s novel Konsulinden (1887; The Consul’s Wife), takes place in the tension between the shut in and the open, between heaviness and weightlessness. The closed space behind the walls of the Copenhagen homes is presented thus:

“The family spent the day from morning to evening in the dark parlour facing into the backyard. Here they ate, worked, and slept – that is to say, once they had dined, the merchant, having loosened his collar and unbuttoned his waistcoat, took his long, perpetual after-dinner nap while his wife sat nodding in her chair, and the child was dying of impatience, forced to sit still and not make any noise in the hot atmosphere heavy with the reek of cooking, to the monotonous sound of the father’s snoring and the slow rattling of the mother’s knitting needles.”

The open forum in the halls of the bourgeoisie is presented thus: “Standing in the doorway, Elisabeth was dazzled. It looked as if the fairy palace had been made real. The ballroom, glistening with candle flames, was momentarily confusing; some young women had gathered directly under the mighty chandelier in the centre, in a spot that was a little darker than the rest of the room, and it looked to Elisabeth as if she was separated from them by a shining fence of slanting streaks of light playing on the bright dresses of the young women on the outer edge, their jewellery and white shoulders. She hardly dared walk towards them; the group had fallen silent, they were all watching the stranger, and Elisabeth could feel their gaze even though her eyelids were weighed down as if it were impossible to look up, while her lips, which wanted to smile, twisted into a wooden grimace.”

In the parlour in which the young woman has grown up, obedience has materialised in narrowness, intrusive odours, and monotonous sounds – it is textural and solid. In contrast, the ballroom is weightless and ethereal – a fairy palace of expanse and light – but the point in Olivia Levison’s depiction of the open space is that it is experienced as a shock.

The confusing throng of unknown persons becomes a mass of staring eyes, of streaks of light, of bits of bodies, which assail the figure of Elisabeth and settle upon her – as heaviness, as forced expression. Closed and open twist one into the other – the aggressive intrusiveness of the parlour is replayed in the individual’s encounter with ‘the others’.

The idiom of the novel expresses the same ambiguity as Elisabeth’s experience of space: on the one hand, a sensitive closeness to Elisabeth’s impression and sense perceptions; on the other hand, an impartial and restraining gaze that dissects and analyses. A cynical gaze in which the whole is taken apart in anatomical components – of the father: “the face puffy and red from sleep, the bared throat with grey stubble, the open, toothless mouth”; of Elisabeth, who is ‘seen’ in reflection: “Her skin shone with the singular transparent radiance that indicates amatory or other ecstasy”. The city mindset, in which a general view has vanished and the present moment can only be grasped by means of pin-pointing the detail, is thus part and parcel of the writing. Analogous to this, the novel deals with a woman who only exists in reflection and who is therefore utterly defenceless vis-à-vis the gaze that strikes her – completely dependent on whether it is negative or affirmative.

However, the cool analytical gaze that the narrator directs towards her subject also uncovers a psychological fate. Elisabeth is the victim of a fundamental denial.

The confirmation that opens the novel thus transpires as a lack of affirmation: from her father, mother, the pastor – and from God. She is instead marked out by “some superior force, inhumanly heavy, slowly lowering itself down over her”, a weight that continues to make itself felt in the ballroom scene every time affirmation from the surrounding world fails to materialise.

Compared with Erna Juel-Hansen’s “En Konfirmand” (Sex noveller) (1885; A Confirmation Candidate, in the collection Six Short Stories) the confirmation in Olivia Levison’s Konsulinden (1887; The Consul’s Wife) is both more desperate and more coldly analytical:

“Elisabeth hardly knows what is happening until she sees the pastor in front of her with hands outstretched above her head […] The words fell one by one like cold drops on the top of her head, she sinks under them as if under some superior force, inhumanly heavy, slowly lowering itself down over her. Beside herself, with her hand in the pastor’s, she suddenly bursts into hysterical weeping, bites into her handkerchief, which she crams into her mouth, and she has just enough self-control left to avoid screaming out loud.”

Elisabeth comes from the bottom of the bourgeois ladder. Her father is an upstart – one who has not climbed particularly high up, however – her mother is the daughter of a toff, but she has come down in the world and now has nothing but contempt for her husband’s ill-bred manner. In the power struggle between her parents, Elisabeth has been her mother’s puppet and has thus been hindered in developing a will of her own, a body of her own.

The young woman in Olivia Levison’s Konsulinden has her womanhood ‘confirmed’ in the mirror:

“She stood in there, moved the half-dead flowers out of the way, took the red boxes and longish cases and arranged them. Then took them out one by one. In front of the mirror, Elisabeth tried on brooches and bracelets, unhooked earrings and put them in, fanned herself and examined the result, full face and in profile. She was now really in her element.”

After the confirmation, food odours are supplemented by the eroticised atmosphere of the ballroom, but it is the mother who, being the brains behind Elisabeth the young woman, “celebrated her daughter’s triumphs, sat at home like a General who sends his army into battle and laid plans for the next campaign”.

Adda Ravnkilde’s Elisabeth acquired identity through Høegh’s words, and the process is almost the same for Olivia Levison’s Elisabeth, marked by a few throwaway words from a young painter: “[…] ‘what are you afraid of? I mean, you’re beautiful…– ’

“It gave a start deep inside Elisabeth’s heart, she felt as if the word sank down and became embedded there.

“Beautiful! Was that true? Really properly true? – She lifted her head and looked around; it seemed odd to her that just a short while ago she had found it difficult to raise her eyelids. Then she walked through the hall with Brandt, who contemplated her with a haughty and well-satisfied smile.”

This man, by the name of Brandt, ignites a “Brand” (fire) in her blood. He too, however, is a parvenu in the milieu. Neither of them has any other right of entry than their pornographic value: they both function as eye-candy for the rich, as game available to be hunted by all. Therefore they cannot have one other; they must prostitute themselves, separately. She does this by marrying the highest bidder, he does it by selling his portraits of the fashionable ladies based on the ‘appetite’ he gives them.

Brandt falls on his feet, whereas the ‘fire’ in Elisabeth becomes an inner self-consumption. Her self-esteem perishes, and thus on her wedding night her husband can devour whatever might be left of her:

“[…] suddenly he grasped with both hands the slender figure, it vanished in his arms, his huge head leaning over it looked like a monster throwing itself on its prey […].”

The remainder of her life is shaped as a variation on this movement: when she resumes her relationship with Brandt and is again let down, when she tries her hand as seducer of a wimpish man, and when she is eventually absorbed in the missionary movement, which can use her title of Councillor’s wife and her money.

The psychological analysis of the novel exposes Elisabeth as an individual who is cut off every time she makes the least hesitant attempt to acquire experience of her own – as in the scene where Brandt ‘draws over’ her slender talent for drawing:

“[…] he corrected them […] took the pencil out of her hand […] guided her small, clammy fingers, trembling in his grasp, to make a few bold strokes, which instantly made it obvious how delicate and diffident the other contours and lines were.”

Everywhere she goes she is treated as furniture or titbit, and the “delicate” aspect of her lines never becomes anything other than characterless. She is and remains an upstart who is checkmated between the urge towards “animal gratification” and the urge towards madness.

The painter – a character who features with conspicuous frequency – produces a concentration of the woman author’s dual gaze on the gender. Here he appears in Olivia Levison’s Konsulinden, contemplating the young woman with a half ironic, half scientific gaze:

“Now he saw how her eyelids quivered; they drew together blinking, the features took on an almost sickly appearance, the head slumped as if something was weighing it down. Interested, unthinking, Brandt stood still, his artist’s eye fascinated by the phenomenon he observed, studied.”

Konsulinden is a complex work of art in which the contemporaneous duality of nervous spleen and naturalistic microscoping has scratched itself into the text. The novel is written from the base of a female experience of being split in two, a condition that was typical for the period. Written from a vantage point located at the intersection between the eyes looking out and the eyes looking in. In the guise of the parvenu, the novel thus pens the woman author’s desperation at writing herself free of the gender role, out to the other side of the window pane, and in the same instant finding herself cast back on an anonymised gender. Taking over as writer and at the same time being taken over – by the public gaze, by the writing.

Settings

Olivia Levison (1847-1894) adopted all things modern with a passion, but at the same time she was “Indespærret” (confined), as one of her short stories was called – by family, by cultural tradition, and by her own sense of being an upstart, not good enough.

Like most of the Modern Breakthrough women, she found a niche in the Brandes circle, which inspired her intellectually but also maintained her diffident image as reflected in a male mirror, fuelling doubt about her identity as a writer. In her youth, this image was apparent in her eroticised relationship with the writer Erik Skram, which led to a correspondence on literary subjects in which she often expressed herself with surprising certainty and authority. It is moving – shocking to see how swiftly she is prepared to pull back when Skram unfortunately criticises her own literary efforts: “But on that subject we can readily agree: this is not art, and I am not an artist.”

Olivia Levison’s life and works manifest, in concentrated form, the extremes which the Modern Breakthrough woman had to span. At one end of the spectrum: a daughter’s role, an existence which in Levison’s case lasted for forty years and was further exacerbated by the patriarchal family culture in her Jewish home; a readiness to wipe out her identity as writer – and, under the pseudonym “Silvia Bennet”, a writing career that largely came to a standstill after it peaked with Konsulinden in 1887.

At the other end of the spectrum, here was a woman ready to go to the opposite extremes. After her mother’s death in 1884, she broke out of her daughterly existence at a stroke: got married and moved to Stockholm with her Swedish husband, a music reviewer. Three years later and she was back home, divorced, but now with her own apartment and her own identity: “O. W. Sandström – Authoress”. And a woman who was one of the few to voice her opinion during the public “sædelighedsfejde” or morality debate, as it was known, commenting from a non-mainstream – realistic and unimpressed – perspective.

A contribution to the debate about moral conduct, written by “Silvia Bennet” in the newspaper Politiken (8 February 1887):

“From the solid basis of Dukkehjemmet (A Doll’s House) to the dizzy heights of Handsken (The Gauntlet) a tower has been built like the one in Pisa, but considerably less solid. Have we women not suffered from the word woman since that time? Has it not been sumptuous for us, unctuous to the extent that we are tempted to return to the taboo lady or perhaps more likely the rural womenfolk.

Yes, womenfolk. People of the female sex, but people nonetheless, not cattle.”

As creative artist she threw herself with a passion into the naturalistic presentation of reality; she was ambitious and worked intently to give her prose an impressionistic approach – to make it an expression of a modern consciousness.

In her contributions to the morality debate, Olivia Levison proposed two, indeed three different strategies that could lead to a dignified life for a woman. The reform strategy – “[…] bring them up to trust in themselves, equip them in the way we equip sons” – is in keeping with the practical work to improve women’s educational and career opportunities, which was being undertaken by Dansk Kvindesamfund [Danish Women’s Society] alongside the officious care of morality. The second approach was also practical, albeit heading in a completely opposite direction:

“Designate girls to be wives, bring them up with a view to marriage as the only or the best prospect, well, that might be fine and natural. But, in such case, then allow them to get married ‘in season’, while they are young, while the amatory instinct is at its most intense, before they are spoiled and slackened by reading novels, dreaming to music, half-suppressed little affairs of the heart, and years of tortuous waiting.”

She practices non-dogmatic realism that takes the existing ‘nature’ into account, but also reinterprets it from the perspective of a naturalistic concept of instinct – and in so doing implies the third strategy: self-fulfilment, in which sexual energy is not stunted by “reading novels” and “dreaming to music”, but is released and rendered personal in artistic creativity.

The strategies alternated in Olivia Levison’s life – in her art they were joined together to a form in which the cracks bear witness to the inner tension. In the story “Indespærret” (Confined), from the collection Gjæringstid. Kvindebilleder (1881; Time of Upheaval. Pictures of Women), the central character, Ulla, is thrown back and forth in just such a filter of approaches that take each their direction. The young, impecunious woman has prepared herself for a survival strategy as teacher when the man – the first-person narrator – enters her life. He punctures her ‘armour’ of self-control and makes the passions flow. In artistic – and sexual – abandonment. But then he takes fright, withdraws, and Ulla is not in a position to pull the separate strategies – work, marriage, art – together.

The woman as the disquieting mirror of the male first-person narrator in Olivia Levison’s “Indespærret” (Confined) from Gjæringstid (1881; Time of Upheaval):

“At that moment she was indeed beautiful; the proud bearing and the defiant mien splendidly matched her vigorous figure, two softly glistening and ample tresses swung back and forth to her brisk movement, and a freshly-plucked rose had been thrust into her hair just above the one ear […] But when I looked at her again, I became almost appalled. Her pallor, quivering nostrils, and rapid breathing indicated great agitation, she seemed not to hear the storm of applause that erupted when the artist withdrew.”

As a woman she is consigned to a social situation where the man is the point of crystallisation, and when he vanishes so, too, does the structure in the artistic-sexual force field, and she ends up as a fairground performer.

The story tells us that the one dimension of a woman’s life cannot be introduced as experience in the other dimension. The text, however, renders interrupted empiricism as a modern aesthetics – a naturalism that, in its visual and fragmented form demonstrates how the eye–catching device has undermined the Romantic vision of totality.

Olivia Levison was twenty-seven years old when she made her publishing debut with the short story collection Min Første Bog. Fortællinger (1874; My First Book. Stories). It contains three stories written in keeping with the Biedermeier frame narrative, but with the experimental use of first-person narrator both as observer and participator.

In terms of literary history – and personal biography – the story “Liv for Liv” (Life for Life) is interesting given that the intellectual development of the female central character is both promoted and inhibited by an eroticised relationship with a man who shares a conspicuously large number of features with Georg Brandes. Her development therefore takes place “in a constrained fashion and without a great deal of awareness on my part; for I received everything from him: I knew no other explanation.” This is the paradox encountered by the Modern Breakthrough woman: liberated from the drawing room, only to be bound even more firmly to reflection in the male gaze.

Another aspect of the short story collection also showed that Olivia Levison was quick off the mark. Several years before Herman Bang developed the city text par excellence – journalism – Olivia Levison, in the story “Paa Landet” (In the Country), inscribed the modern fragmentation of consciousness into the language she used:

“Embankment; a group of men and women, up the slope something, something slimy, motionless, and yet odiously dangling and slack; deathly stillness – finally a head; a bluish pallid, contorted face with staring eyes and streaked, heavy hair hanging down – Hanne’s face!”

Syntax disintegrates, prose is staccato like a pulse running amok – and in accompaniment the narrator ‘swoons’.

The collection Gjæringstid (1881; Time of Upheaval) contains some of the most desperate prose writing of the Modern Breakthrough. The most delicate, sensitive passages side by side with the coarsest of expressive segments. The stories are of an erotic nature, but most have no clear plot. The style is uneasy, ragged, and in many places the meanings are displaced into the secondary meanings of secondary meanings – as in the outdoor setting in “Nummer To” (Number Two):

“Down by the beach it was different. They sat down out on the large rocks, between which the water continually ran in and spread out like a huge fan edged with greyish-brown, fluffy down, clattering with the pebbles and occasionally sending icy splashes into the faces of the two sitting hand in hand watching the waves. The milk-coloured, foaming crests poured down, and on the shore arose steep, brown-green, opaque glass walls which gradually tipped forwards and snapped with a sharp, whooshing hiss.”

The movements have no specific direction – they go in, spread, go up, down, rise, tip forward until they break; the colours are turbid – greyish-brown, milky, brown-green; the materials are variable – now liquid, now glassy. Similarly, the erotically-charged movements in the short stories are chaotic, with no defined destination. Nevertheless, all the stories are composed of thoroughly eroticised scenes where passion is revealed in that which is held back – and in the abrupt reversal:

“The eyes twinkled with shiny, steel-blue flashes of light, she felt like laughing, teasing, playing the coquette, she threw herself back on the seat, stretched and fanned herself with her small lean hands. The Brazilian regarded her in silence, observant and with professional eyes. She suddenly yielded to her desire and laughed […].”

In this passage the coquette from “Modedamer” is making eyes with a “silence” that proves to hold the menace of a beast of prey.

The coquette – the female response to the times. In Olivia Levison’s “Modedamer” (Ladies of Fashion) from Gjæringstid (1881; Time of Upheaval), she is a figure in transition between body and form:

“He reached out for Miss Julie, who had no difficulty in avoiding him; the slightest movement of the small, slender figure was full of a studied and unerring grace, the slim face was of a clear and perfect paleness, under the eyes a slight hollow and the plump lips were colourless and slack. The consummate elegance of her dress, its soft, harmonious colours suited so excellently the fine, calm, and calculated grace of the entire figure that this exterior caused a singular kind of pleasure: a pleasure like a work of art, a painting or a statue.”

In “Indespærret” the passion of the central character is both more pent-up and more vehement – overwrought, as the male first-person narrator says – when it erupts:

“[…] her whole body shook and seemed to be half in a swoon. But she suddenly looked up, tossed her head back, and energetically threw her arms around me. – In the next instant she had leapt up and out of the pavilion.”

The characters in the stories might indeed be realistically rooted in their milieu, but at the same time they are in some indefinable way also outsiders. In “Indespærret” we find ourselves mixing with a shabby, semi-proletarianised bourgeoisie; in “Loreley” and “Modedamer” with the fashionable, travelled society; and in “En Brevvexling” (A Correspondence) and “Nummer To” with the higher, cultivated bourgeoisie. Corresponding to this, the first-person narrator in “Indespærret” is an evasive specimen – half scientist, half something undisclosed – and in “Loreley” he is even more blurry. Similarly, the female main characters in “Modedamer” and “Nummer To” move on the periphery of their milieus – the former as coquette, the latter as a marginalised artistic figure.

A recurring configuration is that of the inscrutable woman who interests and excites a male observer. He approaches, watches, makes a cautious first move and, apart from in “En Brevvexling”, he advances and pulls back – forward and back. He has no idea what to do with the woman’s smouldering passion. She flares up, he gets fired up but tries to stifle the dangerous flames. Looked at from one perspective, it is the female sexuality that is diffuse and omnipresent; seen from another angle, however, we have a sexualised masculinity that dare not face up to its desire. In this respect, Olivia Levison uses the frame narrative in a modern fashion. Unlike the Biedermeier frame narrative, in which the narrator binds the account to an interpretation – a truth – Olivia Levison’s narrator is just as volatile and unstable as the characters being described. It is the tension between what the partisan narrator perceives and what he does not appraise but pins down in details that creates a catastrophic zone: a gaze that “momentarily glanced down […] A dull, deep flush rose up from her throat across her cheek and ear, faded and vanished.” The narrator believes he is an observer, but exposes himself as the instigator of a sexually charged game that overpowers him.

Gjæringstid taps into the sexual unrest of the times; from one moment to the next the mind was obliged to adapt to chance ‘encounters’ – intense or idle togetherness with no other development than beginning and cessation. The fragments, with the epic continuity chopped up into scenes, situations, and glimpses, record the coquette and the female fairground performer as a response to the modern climate of consciousness.

Olivia Levison’s silence after Konsulinden has to be interpreted as her response. It was only by means of restraint and ‘confinement’ that she could keep desperation at bay.

Cunning

Illa Christensen (1851-1922) was certainly not any kind of social upstart. She came from an artistic background with deep roots in the official class. Almost her entire writing career nonetheless addressed the battle to be recognised and the psychological damage caused by living as a fighter. Equally, her imposing pseudonym “F. C. van der Burgh” suggests that she was not unfamiliar with the upstart’s urge for embellishment. The most substantial part of her output consists of four novels and two collections of short stories, published in quick succession from 1884 to 1890.

Skitser (1884; Sketches) is Illa Christensen’s first book. It was published when she was a thirty-three-year-“old girl” – eleven years after her former fiancé had died of tuberculosis. As in this case, her writing was mainly centred in the higher, culturally dominating bourgeoisie – in the theatres and salons of the city, in the holidaymakers’ railway carriages, and in cosmopolitan hotel foyers – but a sidelong glance is also cast at the go-getters and ‘philistines’ of the petite bourgeoisie.

One special feature of Illa Christensen’s style is animism. This is no Romantic understanding of nature, however – nature is endowed with spirit in a gracefully dancing balance between sentimentality and irony, and in a manner which calls attention to the “stemningsmaleri”, mood-painting, as fiction.

Romantic sensitivity in Illa Christensen’s Skitser (1884; Sketches) – but proffered with tongue in cheek:

“Something was in the offing for her, she felt it, the May breeze, the sun and the waves were saying so in a language that Christian Winther had taught her to understand.”

The first collection of sketches was, all told, a matter of fictions. Erotically-charged fictions in which the glimpse of a stranger has made an intense impression on the woman – “She had not forgotten the back of that neck and those shoulders, she had instantly recognised them here this evening” – or the aesthetic fiction in which the music “elevates” sensation from the commonplace “shortfall”: “ – entirely! entirely! it had to be, otherwise it was no good; entirely wonderful; entirely jubilant! a little shortfall and her entire delight lay with broken wing.”

Or – as in the short story “En Skæbne” (A Fate), which is a kind of preliminary study for En Søn – the fictions disempower the person and thereby become fate. Unlike the novel’s upstart, the short story’s upstart ends up committing suicide. A ‘legacy’ from his father and paternal grandfather, a legacy he has spent his whole life trying to repress – and, in so doing, one that has controlled him. Enervated by the obsession that “his name must be polished”, finally there is only the empty theatrical deed left. The closing scene is played out on Kongens Nytorv, a square in the centre of Copenhagen, with street life as the soundscape and the Royal Danish Theatre as the backdrop. The staging of the suicide: a man standing and looking up at the windows of his own home where his wife is flirting and drinking with his friend, and where his own child, sent down to the street for more drink, is his ‘accidental’ co-actor. The son is also dragged to his death when his father walks out of the scene, out of the city, and out onto the ice – which breaks.

In Illa Christensen’s writing, as in the works by Olivia Levison, the setting has taken over the story – and the characters. They assume the pose of the flâneur and the coquette, but despite – or precisely because of – their blasé attitude, they are vulnerable. For they are not stirred by personal incentives, but by impulses that possess them. Eyes looking from outside – pressure from within. A female counterpart to the go-getter has the central role in “Et Kys” (A Kiss). A woman, struck! On the surface by a kiss, which stems from her own flirting, but more disastrously – struck by an inward loss of control:

“She did not scream, she did not swoon and let him revive her, she just dashed like an arrow into the opposite corner of the room, where she sank down onto a low wooden stool.

“With one hand gathering up the torn-off scarf, with the other over her eyes, she sat rocking back and forth, back and forth, like someone suffering great physical pain […] As if in a dream, she heard him rummaging noisily around, worse and worse, becoming utterly deafening, he moved the large painting to and fro, kicked tripods, knocked over crates and easels, while maulsticks and brushes rolled around as if they were crazy.”

The loss of self experienced by the characters corresponds to the accumulation of non-hierarchical statements. “As if in a dream”, the motivating central perspective is missing. Illa Christensen accompanies this impressionistic technique with a teasing tone, a playful escapade with the characters – with the fiction.

Like the women writers of the Modern Breakthrough, Herman Bang developed and perfected a literary form of impressionism – which contributed to an intensification of the contrast between his work and that of the more dogma-regulated naturalism. In an article titled “Impressionisme. En lille Replik” (Impressionism; a Brief Remark), published in the journal Tilskueren (1890; The Spectator) and written as a polemic against Erik Skram’s ideas, he outlines an impressionist poetics:

“The impressionist is indeed ‘privy to this secret concerning our life in nature and between people’.

And the surplus which he believes people through art may be brought to see is precisely the sum of thoughts that are contained in the actions and which are reflected in them.

Like all art, the impressionistic narrative art, too, will give an account of human emotions and of human inner life. But it shuns all direct elucidation and only shows us people’s emotions in a series of mirrors – their deeds.”

In Skitser. Anden Samling (1886; Sketches. Second Collection), the stories play on the transition between the satanic and the humorous, shiftlessness and the vulnerable – the flâneur’s attitude converted into words.

The idler, as sketched by Illa Christensen in “Dagtyve” – og Arbejdsdage (1889; “Idling Away the Days” – and Working Days):

“Francois did not work, he aestheticised, and to his mind that was the worthiest pastime for a human being, – machines were the liberation of the mind – it was actually a mistake that God had created us with muscles, nerves were what we needed.”

The language vibrates with ambiguity. As the sounds and the light and the forms hit the nervous system, the flickering space is present in the metonymic style, with the parts superseding the totality – “and the mass of umbrellas that were out that evening”. Inserted parentheses: “(Very softly)”, and outright stage directions: “A Gentleman: ‘it should not be forgotten […]’” – help give the stories an ambience of hectic, hasty city life. The concentrated situation, the observed line in which personality and occurrence are sketched in one stroke, is Illa Christensen’s form. Thus, a young woman’s person and destiny are captured by the male observing first-person on the train journey in the story “Reddet” (Saved):

“[…] and finally her little foot, which she had turned in a childlike fashion so that the sole was visible, was shod in a sensible, stout leather shoe; this slightly dusty, slightly shabby shoe was of such sweetness in my eyes that I would happily have looked at it for the entire journey […].”

In addition, the narrator is spot on: aestheticising onlooker to life. He saves himself; she, despite the stout leather shoe, does not save herself!

Not only is Illa Christensen in command of the impressionistic technique – she develops it. Uncertainty about subject/object, outside/inside is exploited with both dramatic and epic effect in the picture of the face behind the window in the story “I Skygge” (In Shadow): “The thing was, that behind the small, gloomy window in Læderstræde a sweet, young female face could be seen, at first somewhat coyly downhearted, then more and more tired and pale, – eventually it disappeared altogether […].

After a while, a child’s face emerged behind the window pane, where it had continued to show itself until it could be called a young girl’s face, right up until this moment, when it could be called an old girl’s face.”

In an instant, the nameless need is distilled into its infinite perspective.

In the novel “Dagtyve” – og Arbejdsdage (1889; “Idling Away the Days” – and Working Days), this “window pane” is a psychological structure in both the male and the female central character. They are ravaged by the fellow traveller of the blasé attitude – satiety, fatigue, distaste:

“She sat down by the bed […] she was tired, a little sleepy, felt a little cold, had quite a headache, and was so despondent, alas! so extremely despondent! – oh! the strap broke, and she could not get her boot on properly, she left it dangling from her foot and laid her head listlessly against the bedpost, – she stayed sitting thus, without weeping, without thinking, merely with the feeling of having been deposited, arbitrarily, both in life and at this very moment […].”

Deposited! On the lowest flame – not really sleepy, not really cold, no weeping or passion, merely …

The novel has a number of suggestions as to how this modern spleen devastates lives. The young woman has, for example, a lady of fashion for a sister; she ends up losing her mind. In both a concrete and figurative sense, the corset prevents the vain woman from ‘eating her fill’ – insanity is the final escape route from the objectified body. In Illa Christensen’s novels, however, the central characters mostly marshal themselves on simple fare and in so doing they lay the groundwork where “Øjeblikket” (The Moment) can, in spite of everything, combine with “Tilværelsen” (Existence) – the boot can be mended even though the strap is broken! In the sketches, however, the moment is the prevailing element, cunning is the mainstay – as theme, as narrator who is both knowing and unknowing, as characters who deceive one another and themselves. Ironically, this playing with fictions is what links fiction and reality and holds the madness at bay.

Illa Christensen possessed the elasticity of mind and word that forbore. But she had to cut her writing career short when her mother went blind. Like a good daughter she retired – I Foyeren (In the Foyer), as her one-acter of 1890 is so tellingly titled.

Situations

Betty Borchsenius (1850-1890) did not have this kind of mental suppleness. In a slim collection of short stories, Situationer (1884; Situations), the scream has escaped restraint: “Can the scream not be arrested in the throat so as to catch one’s breath for a new life?” exclaims the enigmatic narrator of the last story.

Like those written by Illa Christensen, these texts generally attempt to render the modern sentiment of existence in aesthetic form. The humour, irony, the satanic cynicism, and the exaggerated bombast are tried out in these “Situationer”, but the elasticity, which in Illa Christensen’s writing causes the various strings to play together, is lacking in Betty Borchsenius’s five untitled sketches. The scream has indeed been arrested, has not been rendered in coherent form, and the writing has been shattered into glinting pieces.

Long sequences are purely scenic, and the meaning is so quiveringly fragile that it seems to be sucked into the discourse: “Forever ‘Farewell’ and ‘Goodnight’, – and ‘such weather’ – ‘lift your

dress well up otherwise you will have it ruined’, – ‘lend me a needle’, – ‘Thank goodness we do not have far to go’, – ‘Yes, indeed I shall by Jove’, said a youthful voice, well pleased, – – ‘do you not regret, Canditatus Holm, that you have promised to accompany me?’”

An utterly pointilist soundscape – but the context fades away, as it did in Betty Borchsenius’s life, too. While writing her short stories, she abandoned her acting career. Things crowded in on her and she became insane. Both in writing and in life, Betty Borchsenius thus exposed the schizophrenic chord that was the sounding board for a woman’s Modern Breakthrough.

The Madhouse

City attitudes were not restricted to the street scene. Here we are in the waiting room of the doctor of mental illness in Amalie Skram’s novel Professor Hieronimus:

“The room was long and gloomy, with a bare floor, yellow benches against the walls, and a large, conspicuously-placed spittoon. There were two men in the room, a farmer who was slouched forward with his hands between his knees and his head deeply bowed, and a younger fellow who looked like an artisan or teacher, with a grimy, jaundiced face and a mass of unkempt, lifeless hair.

“Knut and Else sat down on the bench across from the artisan, who seemed deeply absorbed in the open newspaper he held in his hands. A few minutes later, he glanced shyly up from the paper, and when he encountered Else’s scrutiny, gave her a somewhat embarrassed, yet superior smile, as if to say: ‘You realize, of course, that I’m not sitting here on my own account.’”

Just as individuals in the streets, trains, department stores of the modern city are bombarded by impressions over which they have no personal control, these characters are not thrown together because they have any kind of business with one another. On the contrary, they have no business whatsoever with one another; they are there by virtue of an impersonal service – the hospital service – which they individually have a private reason to seek out. The puppet-like persons present in the waiting room compress both a general exposure and a general confinement – in the hospital, in themselves.

The verbalisation of more and more areas of life, on the one hand, and the general crisis of values, on the other hand, proved a breading ground for a new science. This was the era in which modern psychiatry was born, and ‘the mad’ were given a label and placed in institutions established to accommodate the condition – imposing edifices, which closed in around those who could not cope with the upheaval of the times. A number of the Modern Breakthrough women were hospitalised for one or more periods of time – partly because they were party to the same scientific mindset that laid down the premises for psychiatry and partly because they were outside the system of societal norms anyway, both as women and as creative artists.

In 1891 Knud Pontoppidan, the captain of modern Danish psychiatry, held a series of lectures in which he as a doctor claimed a monopoly on the verbalisation of insanity:

“It is a common misunderstanding that psychological therapy consists of really ‘talking it through’ with the patient, and that in this the doctor of mental illness needs to exercise his entire dialectical skill and brilliance […] for the more opportunity the ill person has to document his case, the more it is to be feared that his false convictions become fixated.”

Symbolising the Agony of Life

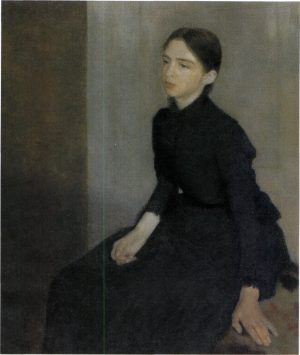

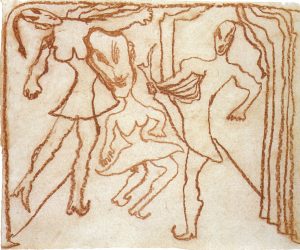

“Oh God – she couldn’t get it right – she couldn’t get it right!” What Else Kant, in the novel Professor Hieronimus (1895; Eng tr. Under Observation, 1992) could not ‘get right’ is a large painting that “was supposed to symbolise the agony of life”, but instead looks like “a miserable fool with tacked-on black wings – a character from a masquerade.” Not only has Else no control of the material, but the figure even starts living its own life and pulling defiant faces at her: “Oh the expression around the mouth – that terrible rebellious expression around the mouth!” Similarly, she is beginning to lose contact with her body. Even though she is fading from lack of sleep, she cannot sleep, or rather: subconscious, corporeal manifestations prevent her from letting go; they gush forth as hallucinations, as neurotic coughing, as a feeling that her head is splitting in two.

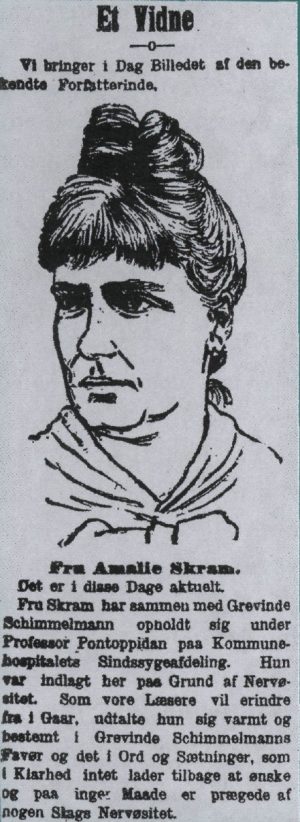

This also happened to Else’s author, Amalie Skram, in 1894. She short-circuited, the mental grid burnt out, and so, as a modern person, she went to science – to the doctor – to get it repaired. She was hospitalised in Copenhagen under the care of psychiatrist Knud Pontoppidan, a man known for his modern views. Things did not transpire according to her expectations, however – rather than being protected and pampered, she was subjected to a ruthless demand for unconditional “subordination”. Her stay in Ward 6 thus turned into a life-and-death struggle with Pontoppidan. He won the first battle and forced through her transfer to a so-called ‘mental hospital’, Sct. Hans Hospital, but when the consultant psychiatrist there allowed her release after a month or so, she won: she went home and wrote Professor Hieronimus and its sequel Paa St. Jørgen (1895; At St Jørgen), an indignant indictment of psychiatry in general and Pontoppidan in particular. The two novels gave her an artistic victory and were a weapon in the ‘mad movement’, which some years later was a potent contributory factor to Pontoppidan’s resignation from his position as director of psychiatric care at the Copenhagen hospital.

In 1897 Knud Pontoppidan published a form of apologia: 6te Afdelings Jammersminde (Memory of Lament from Ward 6). He quotes from a letter he had written to Amalie Skram:

“I have, however, derived much benefit from making the acquaintance of ‘Professor Hieronymus’. It is a capital book – for the person able to read it rightly. It gives a life-like depiction of how an insane person’s rancorous indignation warps her outlook and causes her distorted perceptions.”

As naturalistic works, the two novels bear witness to the pressure – pressure of form – that drove a writer like Amalie Skram to a forum in which a Pontoppidan could play ‘author’. A striking and fundamental feature of the waiting room scene is thus the objective – neutral – narrator. The narrator is ‘covered’ by Else, and in principle nothing other than what Else can perceive, sense, deduce can be written or described. The text is constructed as an uninterrupted inner monologue, in which everything – as good as everything – that Else notices, is committed to print. But it is precisely by this means that an inherent tension is injected into the text: Else experiences in moments – whereas the text ‘glides’ from detail to detail. In places it even takes on the character of medical records or case notes.

A scrupulously recording eye has a good grip on what is happening; the phenomenal world is registered with clinical accuracy in all its nuance and detail. By that means, however, reality clings to the text. The concreteness of things, the details take over, and the gaze gets lost in the material.

Fundamentally, it is this material – “it” – Else cannot ‘get right’. It is therefore that she flees into the madhouse, where the fiendish irony of the novel ensures she is assaulted by precisely “it”: “There they were again, inside her head, those lions and tigers and Hell-hounds. No, it was the maniacs. Ten of them. Imagine all of them having room in there. If only they didn’t split her head open. They would fly in all directions and it would be so hard to find them when her head was put back together again.”

Anguished and exhausted from lack of sleep, she is assailed by the sounds of the hospital – the noise of “the maniacs”. They are a floor below her; she cannot see them and recognise them as human beings, but only experience them as sound projectiles invading her body. And that is her vulnerable point. Her very reason for agreeing to hospitalisation in the first place is that her normal defence mechanisms are damaged. She has lost the ability to ‘overlook’ – everything penetrates her porous surface.

Over the course of the two novels, Else gradually regains her health – not at one stroke and not in full, but enough so that she can leave the institution with a stabilised sense of self. She is able to pull herself together largely because her artistic conflict is completely displaced by an actual enemy: Professor Hieronimus. The aggressive erotic tension between the two marshals her energies and changes the world from an amorphous “it” to a visible opposition she can lash out at, a solid ground she can depart from – and hate.

Her compulsive focus on the person of Hieronimus and her deepening anxiety at the beginning of her stay in the hospital show that the ‘treatment’ could just as well have resulted in Else not re-establishing her sense of self. That she does so anyway is not thanks to Hieronimus.

One of the decisive aggravations to Else’s condition is brought about by her abrupt realisation of her position: she simply does not have one! Up until this moment, she has explained away, refused to believe that her arguments were not being heard; she now suddenly realises that she does not exist as subject in this system, she is a number – a ‘something’. Her reaction to this realisation is a stiffening, and the following night she fights her decisive Jacob’s battle: “Her eyes closed, but sleep was far away.

“Then the woman who committed suicide was beside her again. But now her breath wasn’t rattling. Unmoving and quite naked under a sheet, she lay on Else’s blanket. Else distinctly felt the cold emanating from her dead body, and the stench of carbolic acid blended with the smell of the corpse.

“Else wanted to scream and open her eyes, but it was no use. The corpse had glided onto her chest and was suffocating her. She struggled violently for air, for the power to move. But she couldn’t lift a finger. Now she was dying – she was dying. Oh God, she was dying after all, suffocated to death by this unknown suicide. She was dead already. There was just a tiny little place inside her head, at the very top, that was still alive. The last remnant of bodily life had retreated to that place, where the fear of death bored like a red-hot spike.”

As in the ‘realistic’ sequences, this ‘surrealistic’ episode glides along the sensations – sound, movement, sight, temperature, and smell – and it is notable that the boundary between subject and object is not respected. Else’s inner body is subjected to exactly the same kind of gliding as along the outer body of the imaginary corpse – here the boundaries have been erased. Else has been depersonalised; the corpse, or the limbs, go into operation. The logical – naturalistic – consequence would be silence. But instead a free-flowing imagery is released, in which madness is graphically portrayed. The scene marks a turning-point, a symbolic rendition of Else’s own death. In spite of – or perhaps, on the contrary, by virtue of – not having a voice in the discourse of the system, she has been abandoned to her fantasies, has been compelled to endure her own discourse, to get a grip on the shapeless “it” by getting herself into shape.

In Amalie Skram’s Professor Hieronimus (1895; Eng. tr. Under Observation, 1992), locked away in the hospital Else is abandoned to her fantasies:

“She was lying in a semi-conscious state with towering green-stained walls close around her. At the top the walls slanted inward, leaving only a tiny open square, covered by a wire cage with a gas jet burning inside it. A pale twilight flooded down the green-stained walls and she could hear a muffled roar, like the sea rolling monotonously in the distance. Nobody could see her, and the wire cage over the opening would never be taken away, and she would never be pulled up from these depths to life and time, the sounds of which she could dimly perceive. She would lie here forever, lie here with frozen arms and outstretched legs.”

In the writing she is presented as prepared and, once the death process has been lived through, she can again see herself as creative subject. What Else does not think about, but what the text thinks through this scene, is that she momentarily regains not just her ability to open up for her imaginings – they have plagued her throughout – but her ability to shut off, step back, once they have assumed artistic form outside her own person.

The rather peculiar motif for a naturalistic painter, the agony of life, is thus simultaneously explained and delivered: agony for the mad apparitions – for “it” – is the agony of life. Here the symbol of the agony of life is thus painted – not in colour and line, but in writing!

Phantom?

In 1883, some years before Amalie Skram’s hospitalisation, Helga Johansen (1852-1912) had been through a similar experience. Voluntary admission to Københavns Kommunehospital (Copenhagen Municipal Hospital) resulted in forced transfer to the ‘madhouse’, from which she ran away during a walk with her brother when he came to visit her.

Helga Johansen was a trained teacher and, like so many other unmarried women, the solicitous daughter of an ailing mother.

She had a close relationship with her brother, the artist Viggo Johansen, and had therefore come into contact with Georg Brandes, with whom she corresponded. Her oeuvre is sparse and has the clear signs of being ‘notes from a lonely soul’. In her works, social reality only exists as the restraint and force which the voice talking is up against. In her novel Hinsides (1900; Beyond) and in the prophetic Brev til Menneskene (1903; Letter to Humankind) only the pseudonym “Hannah Joël” does the talking, and Rids (1896; Outline), published from the pen of “Et Fruentimmer” (A Woman), consists of three dramatic pieces, of which the two dialogues, “En Times Tid” (An Hour Or So) and “Passiar” (Talk), are more like monologues randomly intersecting one another than conversations. The last piece, “St. Hans Nat” ( Midsummer Night at St Hans), which reaches a dramatic climax when the ‘mental patients’ conspire to set fire to Sct. Hans Hospital, is the only text in Helga Johansen’s oeuvre in which there is some kind of communication between characters. It is, however, communication in which the psychotic voice is heard everywhere – in the light conversation of the bourgeoisie, too.

Like Amalie Skram’s novels, Hinsides is a fictionalisation of its author’s own medical history in 1883, but unlike Else who believes she is ‘taken into account’, the ‘I’ in Helga Johansen’s novel positions herself beyond. The text is played out on an inner stage, and the outer hospital setting is only present as a “performance being given” – from which the occasionally quoted detached fragments of speech merely serve to endow the performance with some comic effect.

The text is ‘strange’, and in long stretches hard to distinguish from psychotic transcript:

“I […] have been thinking on the facade, and have not noticed that words cast shadows that have to be drawn up so that there is a world in which to live. Only now am I sure that it is not the edge jutting out that is important to get hold of – for you have to get away from the main entrance, rush at speed along the soil, then again towards cloud and right around along the eaves, until you find the place you came from. Then only is the word drawn up, and can be arranged among the signs.”

As everywhere in the novel, she is here addressing “the signs of life”, and the story can thus be read as a metatext on the relationship between language and phenomena. Every phenomenon is distilled into its component parts; it is not people who are active in the text, but limbs, hands – and ultimately abstracts. The material attributes are broken down as through a prism, in which movement is isolated in “a world of its own”, and visual elements appear as “dots” and “stripes”. Colours are no longer characteristics of things, but possess a life of their own.

The agenda of the text thus addresses the issue of the phenomenological truth of language. When shattered glasses resemble sugar, the imagery is tried out by the first-person narrator eating the glass dust; when “light engulfs me with a peace”, the metaphor materialises through self-immolation. Language assumes magical powers – it becomes dangerous:

“These folds appal me, now refracted by my arbitrariness and remaining as directions down in the shadows of the gown. I must stare, bewildered and afraid, at all the marks made by my existence here in this world, where I ought not have broken in.”

As in Professor Hieronimus, it is all the intrusiveness from outside that has to be kept at bay. The text is writing itself up against the phenomenal world’s invasion of the subject. Amalie Skram rendered the anonymously threatening as ominous but recognisable specimens – lions, tigers, dogs – whereas in Hinsides, reference to reality is in a constant state of flux. The only fixed point is the ‘I’, all other meanings fluctuate. This leads to an aestheticisation of sense perception. From ascertaining that there is a lack of “red” in the room, the text flows along associative lines to a bleeding hand.

In Helga Johansen’s Hinsides (1900; Beyond), associative flow is the organising principle:

“There is something lacking in the room. The only red is the little star in the ceiling, which keeps watch at night. A solitary little star – and it is not red enough!

“You must hew the stars out yourself and make them better. You can get the stars out in a pane of glass when you smash the window […] It will not make a hole large enough to climb out through, but I can make my hand bleed so it will be more red in here.”

Blood is indeed indisputably red, so the logic is accurate – but absurd. All the other aspects of a bleeding hand – pain, disablement – disappear in the abstract association. Or the text slips into a form of expressionistic colour riot:

“Why have I not previously known that butcher’s shops are beautiful? Yet once I could get as close as I liked and delight in the red meat on white marble.”

This cynical vantage point is a consistent projection of the monological. The surrounding world exists only as a random occasion that triggers specific linguistic transitions.

In principle, these gabblings could continue indefinitely, and yet the text has a kind of progression and ending. Inside the linguistic construct there is a slender strand of storyline, in which Hannah Joël at length succeeds in escaping from the institution. She “chooses to try the light again” – even though the text renders neither perceptible nor probable a process of development in the subject. Herein, however, possibly lies recognition that madness is the follower of freedom:

“Once you have become accustomed to seeing things in instants then you can also see the dots. And having once seen that, without feeling dizzy, then if you want to you can play the game with the stripes without danger.

“I am not yet that far – far from it. All I know is that if I want to be among the others I have to be able to gather the light stripe together again. That is hard, because I see the chasm between each moment. It is just leap after leap. There will never be more coherence to depend on, but I ought to be able to do without feeling secure by a phantom. The chasm I will acknowledge, even though I must look away so as not to become dizzy. If it again draws me, I say to it: You are but a dot! As all I await is a moment, you have perished!”

To the last, the writing thus avows skeletonisation of the phenomenal world as an existential condition. Any seeming coherence is rebuffed as “phantom”, whereas the “vision of the instant” endures.

The ‘mad’ speech of the text is thereby in profound concord with the times. The atomised “moment” is, in terms of consciousness, the counterpart to the released, privatised individual. This modern cognition leaves no room for truth, no history that can be carried over into the next moment. Individualisation is penned to its utmost consequence – the surrounding world is not a condition, but a choice.

Via ‘madness’, Helga Johansen wrote herself clear of the “phantom” and onwards to the human being. From this position she later used her Brev til Menneskene to take issue with the ‘isms’ of the Modern Breakthrough:

“To those advancing it was no longer said: Now onwards, every man! but: Now every man on his knees before the concepts! […] They have fashioned for themselves regalia of the grand concepts. The truth they wear on their head as a crown, justice they hold as a sceptre, freedom – that is the orb they play with in their spare hand.”

In contrast to this scheme of things, there is life in which the one person stands face to face with the other: “The objective of the course followed by these two is not the palace, not the cottage, not the learned auditorium, nor the church. The objective is the lodging house, the meeting place.”

Where ‘madness’ was the negative, then naked humanity is the positive consequence of the release of the individual, an ethical obligation to the chance encounter, and the responsibility incurred by the individual in the moment:

“People! We who live in joint community of time! You, who with me draw the breath of life into the realm of the thousand moments, which has come!”

Here Helga Johansen has also taken the aesthetic consequence of having looked madness in the eye. In Brev til Menneskene abstraction and aestheticism have become symbolism and myth.

“There is no audience, when you have a look. Audience, it is a concept that has strayed into the sense perceptions and been allowed to stay there. Audience has become social hallucination: hallucination, which in market value passes for reality.”

Helga Johansen’s disavowal of modernity’s theatre, Brev til Menneskene (1903; Letter to Humankind).

Amalie Skram’s and Helga Johansen’s respective versions of the ‘madhouse’ are similar – and yet not in the least similar – to one another. Both have the Modern Breakthrough’s thinking on emancipation as their frame of understanding, and both exceed this by construing the first-person narrator as a volatile construct and not as a fixed – natural or ideal – identity. But where the pages of Amalie Skram’s books are filled with texturality, Helga Johansen dissolves texturality in an existence that implies other and more dimensions than that of experience.

As far as the history of literature is concerned, they represent two different phases in the development of literature written by women: from Amalie Skram’s naturalism through a surrealism, which here in the mid-1890s was becoming increasingly conspicuous in her writing, to Helga Johansen’s monological stream, which points ahead to twentieth-century experimental prose. At the same time, they cultivate trends present everywhere in the female Breakthrough. But each in her way takes her pen out to where the aesthetics and the cognitive forms of the Modern Breakthrough undergo a transformation.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch