The debate about the incomprehensibility of the young female poets, provoked by the reception of Ann Jäderlund’s poetry collection Som en gång varit äng (1988; Which Had Once Been Meadows), would later also become about Katarina Frostenson and Birgitta Lillpers. They are all accused of writing impenetrably, but these three become the central figures of the period. They emerge from a decade of straightforward everyday poetry, and now begin to investigate the slippage between language and the world. They prove its existence, use it, and play with it. There is really nothing to warrant that a hat is called a ‘hat’ – this is merely a convention. Our everyday language – when we say “would you like some more milk”, or “the BNP must be increased”, or “I love you” – to them this appears to be an independent and arbitrary system.

Many of the female poets of the 1980s also strive to block intellectual reading in order to show language in action. It can be called a language of the body and the senses.

Are there other common traits? It is characteristic that the female poets cannot say I in a self-asserting manner – and perhaps do not even want to. They turn their backs on the proud modernist striving for an authentic self. The self that is found in their poems is dispersed. This is clearly seen in that its body is disjointed. The poetic speaker can look at his or her hand and not recognise it, or hear his or her own voice and not know where it comes from. “Out of my throat a / voice laughs”, Katarina Frostenson writes. “Think of your hand as a hole / in the other’s head”, or “I see my hands coming / they have come loose / from the piece”, Ann Jäderlund writes. These poems are ownerless.

The reception of Ann Jäderlund’s Som en gång varit äng in some ways was aggressive. The poems were, for instance, called “word compilations on a page in a book without the will to touch upon any subject or contain any understandable import”, as Magnus Ringgren wrote in the Swedish daily Aftonbladet. In the daily newspaper Dagens Nyheter, Åsa Beckman discussed the male critics’ inability to take in female texts; they have never had to learn to transcend gender in their reading. The debate that follows is poisonous, but among others the poet Tobias Berggren sees in the new female poetry a different language disowned by civilisation.

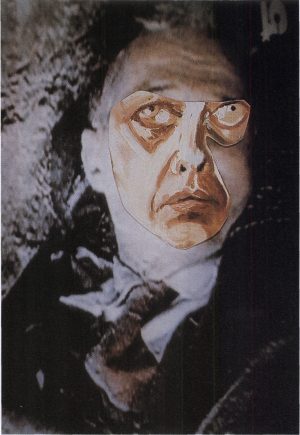

Katarina Frostenson

In 1978, Katarina Frostenson (born 1953) made her debut with I mellan (1978; In Between). The title sounds like it comes from an early and preposition-greedy 1960s, but here the prepositions touch bottom. I mellan is the first book of an authorship of great gravity and integrity that gradually comes to include prose and drama as well. Katarina Frostenson’s poetry has a recurring theme: to see or be seen. This is a drama of life and death.

The pulse of the city beats in her early poems and she often describes walks through peopled streets between modern glass facades. It is a fragmented poetry in which the words are typographically distributed across the pages. The world around her is so flickering and mobile that it is only possible to take in small bits at a time. The poetry only catches fragments of faces, just a few words of passing dialogue, just a few letters from signs. But the flickering is not just outside the poetic self; it even moves inside the body and shatters it. Terrified, the poetic speaker notes what her voice or her hand is doing. It seems impossible to establish a self that is in control of the poem.

Katarina Frostenson’s poetry describes our society as a society of the dead, where everything is clean and well lit. It is a society that must continually disown the low, the dirty, and the dark. And not through repressing it – as might have been done in earlier times – but on the contrary through talking about it, showing it, and discussing it at any cost. This is our modern information society’s way of maintaining order. The practise is terrifying: she has “a feeling that cruelty grows with order”. In her poetry there is a continued attraction to that which breaks the order: betrayal, violence, lies. In the collection I det gula (1985; In the Yellow), a woman sits in a typically Swedish super-practical train compartment:

In a train

with frighteningly organised comfort, regular tight breaths

I find myself loving your evasions of me,

love really love your obvious lies They shine

Betrayal, stands a word in the absolute light betray me, again, again so that I

am filled by the yellow sea

In the collection of poems Den andra (1982; The Other), it is phrased more poetically:

Glossy, smooth, white. Memory, countless

metres of white bandages. White, so that you do not see, come, oh come accident –

come and break down

Katarina Frostenson’s language is often associated with violence. To name is an assault. We cannot bear anything that is dark and hidden: it must be dragged into the light, be seen, be named, and thereby be killed. We are, she finds, obsessed with making words and pictures of everything. And at the same time, she knows that we must speak and write in order not to live in a wordless darkness. This ambivalent attitude towards language is the basic trauma in Katarina Frostenson’s works. It does not appear to be a coquettish aesthetic attitude, but a deeply personal drama.

In her poetry there is a coupling between language and gender. “The name covers”, she writes. The very act of naming is mentioned as something masculine. Language enters everywhere. There are clear parallels between the acorn, the eye, and the word – all want to enter the darkness, penetrate, and dominate. “It glistens. It glistens from the glance that noses its way forward, wanting to penetrate, even deeper,” she writes in the prose poem Stränderna (1989, The Beaches). The word is phallic. “The word rose, like a pillar, stiffened everything around it, / […] / Alone, completely supreme”, she writes, and: “The word stood like a staff. Exterminate, what can be exterminated on a beach. Pull with power, uproot it”.

The ambivalence towards language is a theme throughout her works, but Joner (1991; Ions) displays it most clearly. With this collection, Katarina Frostenson’s authorship condenses and becomes more violent and more dramatic. In Joner, she writes about naming and about being named, about seeing or being seen, about being the rapist or the victim. She does so by mixing images from the rewritten dismemberment of Catrine da Costa, the myth of Artemis and Apollo, and the medieval ballad Jungfrun i hindhamn (The Maiden in Deerskin). All are about the bestial will to drag out, dissect, and see at any cost.

by my hair hangs the voice

I said to I

and I freed myself from I

I looked down my dress

in my dress hangs the voice

I said to I

and I freed myself from I

I looked down my trousers

in my trousers hangs my dress

I said to I

and died

In Joner, Katarina Frostenson problematises the concepts male and female. The positions start to circulate: victim, tormentor, man, and woman trade places. The opposites we are used to apprehending in the world dissolve. Gender identity becomes less a question of biology than a question of one’s position within language: am I someone who defines? Someone who is defined? The power struggle thus takes place within language. The collection contains the central poem “A” in which such a change is described with particular clarity.

“A” has the hunter Actaeon see the virgin goddess Artemis by a spring. In the original myth the hunter Actaeon sees a glimpse of Artemis naked, and as punishment he is turned into a stag and is torn apart by his own dogs. In Frostenson’s version, the poem does begin with the hunter doing the seeing. But in the middle of the poem, in an italicised line, comes the turning point: the goddess looks back. Now, just now, she is the one who takes aim at him. She shoots – and he is destroyed. With the title of the poem, Katarina Frostenson perhaps wishes to underscore the fact that the crime of seeing is equally terrible regardless of who commits it. The letter “A” is a fusion of the two guilty parties.

I saw him, looking at me

at the water’s brow, the spring –

: And if he saw her, did it: if he saw her

without

her seeing

That he saw her stand in the spring, naked –

the back, the edge of the shoulder, the white quiver If he saw her

turn as if from a sound and stripped bare, become completely visible

Then become hidden, with just the one white oval far above the others But

seen The glance that spreads, the thrill of the quiver

I saw him when he saw me now I see

She shoots with the bow

sighted

measured eye

It begins at the top, with a splash, a tan fleck: wrinkles,

a blaze It flows into a patch, spots over the eyes pointy-eared

– All his tan, his tan invisible now not the chest,

the mane, the chest, the hooves, cleft Elevated – filled … out

(sound from the mouth)

The strange thing about Katarina Frostenson’s poetry is that it automatically clarifies other poetry. When one reads her poems, one suddenly becomes conscious of what characterises conventional poetry: how it strives to be cohesive, complete, and balanced. Everything a poem says can often be traced back to a single, central-lyrical voice. That voice is alien to her.

Katarina Frostenson writes as if she does not know of its existence. As soon as a form is perceived, it is immediately rescinded. “Yes, everything that can be said of them must sort of be counter-sung in the same gesture,” she writes in the prose book Berättelser från dom (1992; Tales from Them), but the statement also concerns her poetic method. Here one meets, in a different guise, the same sense of designating language: an aversion towards everything that pretends to be settled, everything that is balanced and complete. Her poetry refuses to perpetrate the same assault. She wants a more direct language, a language of the body and the senses.

In Eva Kristina Olsson’s (born 1958) urhälsningen från mej (1992; The Original Greeting from Me), gender appears to be a strange uniform that is apportioned to us: a collection of cloth and kit that everyone, except the women in the poems, seems to know how to carry. The words appear alien to the poetic speaker. They are things that can be moved about in various fixed combinations.

This is also seen in her debut collection, Brottet (1988; The Crime), which is constructed around a number of central words – horse, man, yellow, block, rat. Here, too, there does not appear to be any obvious link between words and reality. Eva Kristina Olsson’s laconic debut is poignant. The shadow of a tall man falls over the poems. You realise that the poetic speaker was once assaulted, and that since then there has been this gap between language and world. Now she is carefully reconstructing language.

Another specific characteristic of Katarina Frostenson’s poetry is that it never retells, but attempts to bring forth experiences. This is a point of great similarity between Katarina Frostenson and the Concretists of the 1960s. The Concretists saw the poem as an “event”. They advocated the sensual and non-conceptual sides of words in order to break down intellectual understanding. They worked with sounds, rhythms, and resonances, and eschewed the aphoristic and anecdotal. Similarly, Katarina Frostenson works with the language as if it were matter. She may use words consciously to twist or obstruct the experience of the text. If a sense of something tricky or unpleasant is described, the line is tricky in itself. Thus the poem’s lines mould facility, gravity, superficiality, density, or space.

In 1994, Tankarna (1994; Thoughts) was published, a collection wrapped in a very yellow cover. In Katarina Frostenson’s poetry, yellow has always been a positive colour, related to something intense and wordless with which she connects when there is a breakdown of language and order. The yellow colour appears in many of her poems.

In Katarina Frostenson’s poem “I hjärterot” (“At the heart’s root”) we meet Herr Peder. He is out and he sees.Herr Peder fears that what he does not see does not exist, and therefore he must drive an arrow into the darkness. The poem about Herr Peder is violent. The tone is harsh, the sentences brief. There is something uncanny about his behaviour, and the jubilation he breaks into at the end is almost bestial:

Herr Peder is out. Herr

Peder is out to see. Herr

Peder is beside himself. He sees

everything, except the root. What cannot

be seen might not exist –

So he drives in the arrow, drives

it right down into the root. To

see, that place. In an eye’s

lustre – for a moment the world

is visible, joyous to see – and

hear. The black drops of the root.

Spill, your own ink. Then

the face breaks into jubilation –

the heart

In Tankarna, Katarina Frostenson constructs a special country. At the centre is a city. As is often the case in her work, it is a place that hides and disowns. But sounds and notes are occasionally heard from cracks in the facades, streets, and tiles. It is as if this city were built on a song. Outside the city are suburbs, woodlands, fields. They are places of forgetfulness. There lie the dead, half buried in the ground, along with other forgotten gear: “a mint green jacket / in the brown soil.”

In the poems there is one definitive pair of opposites. There is a wastrel family in a suburban apartment reeking of herring. By the kitchen table the language is vicious, as in previous works: “Speak, we are at your root finally / scrape, cover, mend / Voices, pain / accents, violence”. But a positive counterpoint is also introduced: in a rose garden far away a woman strolls while singing, “her mouth-song sounds / a belling, a voice like nothing else”. In between is the poetic speaker, heading for the wordless song of the woman with “a map / […] / beneath the breast”.

The woman in the rose garden is an unusual figure in Frostenson’s poetry. She is light and positive. She lives outside the repressive city, outside language. Her location is open and airy. This woman is the closest one comes to a utopian creation in Frostenson’s oeuvre. The poetic speaker hopes the wind will bring her own voice – associated with speech and language – to that rose garden and forever bury it there.

In Tankarna Katarina Frostenson’s poetic speaker is no longer divided. The body is an entity. The new self can lie blissfully in the grass and speak or sing. She is interacting with the world around her.

I walk on the warm air of the meadow, from the strong garment of the cloth –

happily on the back, in the grass of the hollow: suns, planets

heavenly toys, and stars, stars

make their calm rounds – and the tongue sinks into the throat just

now, and the mouth becomes smooth and swallows everything and all things

and all sounds slide out of me, a serpent again –

Ann Jäderlund

Ann Jäderlund’s (born 1955) debut Vimpelstaden (1985; Pennant Town), does not feature a complete and collected poetic speaker either. The mouth, the eyes, the hands are disconnected, and the poems investigate each part with surprise. Two mouths are attached to a nose and in the intersection between two legs is a heart. A poem may go:

I see my hands approach

They are loose

from the play

I am nobody there, I am nobody there

in the town

As I wobble

through the holes of the night

Ann Jäderlund’s debut collection consists of pure and brief poems, naive and often humorous. In her second book, Som en gång varit äng, she appears to be a poet of love. The collection can be read as though written after a troubling and passionate love story. It is consciously overloaded with heavy floral metaphors. There are huge amounts of flowers, leaves, bouquets, lilies, anemones, but everything appears strangely stylised and lifeless. The meadow was once alive.

Various phrases continue to leak into Katarina Frostenson’s poetry. A commercial slogan may equally well appear in a poem as a quote from the Bible. Behind these leakages is a linguistic philosophy. The quotes are slightly twisted – as if to create the illusion that they are not consciously chosen by the writer. To speak of a language “of one’s own” is impossible, Frostenson shows; everything that has ever been spoken exists in our common language. She lets a few words here, a few beats there seep in from ballads, folksongs, everyday chat, fairy tales, hymns. Literary characters, too, (from works by Carl Jonas Love Almqvist or Aksel Sandemose, and others) parade by, slightly disguised.

In Ann Jäderlund’s poetry, love and trust are constant themes. Love is absolute. It demands the entire human being. In Som en gång varit äng and Snart går jag i sommaren ut (1990; Soon I Will Go into the Summer), there is a dialogue between the female ‘I’ and the male ‘you’, with dramatic shifts between power and submission, between longing for absolute expression, and the terror of losing oneself for good. Love is a struggle, painful and wonderful. “I opened your hand with mine / You slid a finger into my brown throat.”

In Rundkyrka och sjukhuslängor vid vattnet himlen är förgylld av solens sista strålar (1992; Round Church and Hospital Wards by the Water the Sky is Gilded by the Sun’s Last Rays), Ann Jäderlund creates a landscape of love. It is a midpoint between a wild landscape and a disciplined nature. The lovers move here with senses vibrant. The dividing line between body and nature is erased; rocks, water, and valleys merge with muscles, veins, and skin.

It moves well over the ground like a second shading

As the day dies and the sun’s drops fall

Deep within your light from the chamber disappears

And shines the solitary mouth like a wound so red

And even I rest while the blood runs

It is a hide of silk trailed across my cheek

The soft rocks that break in double rows

And tremble for a caress in the foundation of the rock

The collection is divided into 148 four-line stanzas that can be read together as one single poem with different phases. Occasionally, it starts to describe a complex of images – such as women who move through a dance with gilded ribbons in their hands – but soon the imagery is dissolved and disappears. The stanzas seem to strive for a set verse, but are continually disturbed – a syllable drops out, a letter is added. The rhythm creates a feeling of being compelled upon, and perhaps of wanting to be, but at the same time of being on the move, refusing to persevere, wanting away.

At the centre is a female self. But who is the man? “I can’t stand your guises,” the woman says, and that may as well be directed towards a single man as towards several that simply represent each other. The cycle of poems can be read as a description of the various male love objects in a woman’s life, influenced by the very first: the father.

A leading male character is one that has the traits of the heavenly lover. He is tall and powerful. The speaker approaches him from below, she carries forth her body like a sacrifice: “Father I need you and I give you my head.” He sees right through her body. Not even her skin limits him: “The leg is filled with fluids after your thin finger.”

The female speaker in the poem is, as often in the work of Ann Jäderlund, silent. She watches what he is doing, but she does not stop it. The strong emotions seem to occur within herself. This is the desolate female position that Ann Jäderlund has described since Som en gång varit äng. And yet one senses that one of the ambitions in Rundkyrka och sjukhuslängor vid vattnet himlen är förgylld av solens sista strålar is to make the male and female positions mobile, to try to dissolve the deadly gender polarisation.

“I am establishing my realm,” Ann Jäderlund writes in a poem. And her collections can be read as a slow establishing of this realm of her own – a functional language. Let us start with Vimpelstaden. It seems to be written by someone who enters language obliquely: “I entered among words / My heart beat.” The words here appear as absurd and comical, and it seems ludicrous that people try to speak with them.

In her second collection, Som en gång varit äng, Ann Jäderlund takes a step further. The book contains the suite “Natur” (Nature), which was much discussed, not to say vilified, in the ensuing debate. It is one of the decade’s most peculiar suites of poems. Here one follows, right in front of one’s eyes, how the words slowly detach from their usual meanings. The gap between word and world becomes obvious. We get to follow how signifier and signified are separated.

In “Natur”, Ann Jäderlund works with a limited number of words: the moon, the field, the poppy, the pin, the leaf, the seed, the mouth, the breast, and so on. In reading the collection, one learns to identify the words as charged with the male or the female. Words like metal, crystal, rod, and pin are more male; poppy and leaf are closer to the female. In spite of the occasional switching of places – which is what makes the poem great – the polarisation can be clearly seen.

From these words, Ann Jäderlund creates nursery-like rhymes and strongly repetitive poems. In the essay “Le plaisir du texte” (The Pleasure of the Text), Roland Barthes writes about the function of repetition within rites, rhythms, and invocations. To repeat the same word and the same sound, Barthes writes, is a way to lose oneself in the unknown, to reach a stage where signification no longer matters. Then, the sounds and sensual qualities of the words are perceived and awaken joy and eroticism. Playing with repetition, Ann Jäderlund makes exactly this happen. It is as if the meanings start to shift.

The meadow is moist and pretends that the meadow is moist

The leaf is glossy and pretends that the leaf is glossy

The mouth is pretty and pretends that the mouth is pretty

And finally, in the penultimate poem of the suite, she reaches her point. She has made the words hers. Only now can she start to use them herself.

As if it is my meadow

As if it is my leaf

As if it is my lake

As if it is my pin

As if it is my ray

In Rundkyrka och sjukhuslängor vid vattnet himlen är förgylld av solens sista strålar, Ann Jäderlund seems to have established her realm. Language is here less problematic. The poem seems to be written with a sense of being amongst words, with greater access to all of their meanings. The gap between signifier and signified is closing. And the interesting thing is that this realm is established at the very same time that the male-female polarity becomes less important.

In this collection, Ann Jäderlund works multiple shifts into each line, thus creating an image of love as a complex drama. The lines are meant to be stifling with all the steamy blossoms and trembling bodies. The reader is efficiently transported into the same condition as the female speaker of the poems.

The cover of the collection Tankarna was created by Håkan Rehnberg. Katarina Frostenson often collaborates with artists. She has, for instance, written the poem suite “Moira” to paintings by Rehnberg. She has also worked with Jan Håfström, among others. In the Forum Gallery, which Katarina Frostenson is co-owner of, encounters between musicians, artists, and authors are facilitated.

Ann Jäderlund’s interest in the fixed form becomes more obvious. She investigates the tension between creative imagery and a specific, reined-in form. mörker mörka mörkt kristaller (1994; darkness darken dark crystals) is a brief but intense collection, considering its form. The seventy-five poems are written in a semblance of trochaic verse. Here, the special rhythm must consolidate disparate images that are mumbled out, half consciously, in a suggestive way. Ann Jäderlund effortlessly shifts between biblical and Nordic landscapes. The collection is about falling, sinking. It could just as well be about a suicidal drive as about the sinking towards death that is always part of life.

“The world exists (as movement)”, says the female poetic speaker in Maria Gummesson’s (born 1961) triptych Hos ljusmålaren (1989; At the Painter of Light), Hotell Kosmos (1990; Hotel Cosmos), and Drömlös (1993; Dreamless). Her poetry is spontaneous and temperamental; the key word is movement.

In the work of Maria Gummesson, movement also becomes a formal principle: hers is a constantly progressing and ongoing poetry. It consists of swiftly passing words and images: impressions of the city, of nature, and less frequently of people. An image is established only to vanish the next instant: “empty city, sun, some bicycles, shimmering against the backlight, now dissolved.”

Typography is important in her poetry. The words are not prettily arranged, but flow all over the pages. Some words are semi-bold, others italicised, yet others printed upside down. Some poems have been crossed out, arrows and stars are placed along the edges, and in the middle of a poem a time reference may appear (20.52.00). The effects serve a function: the poems must lack a unifying centre. They are in flux.

The woman in the poems shares traits with Hamlet’s Ophelia. Ann Jäderlund gives us glimpses of details from Ophelia’s death by drowning: the water, the nettles, all the flowers. Ann Jäderlund follows the fall of her poetic speaker through the poems with solicitude. It is obvious that the Ophelia figure fascinates her. In Shakespeare’s play, everyone – men and women – want Ophelia, while she only sinks. The experience of being the prey is constant in Ann Jäderlund’s books. In her works, woman is a chased virgin – but also an unusually self-conscious victim.

Birgitta Lillpers

Birgitta Lillpers’s (born 1958) poetry is set in the countryside – light years from urban city poetry. The environment characteristic of her writings is established in her very first book, Stämnoja (1982; Dischord). Her settings could exist somewhere in Sweden. There are farms, woods, fields, town streets, small town squares. But suddenly she brings in something unexpected that makes the text slide away from the illusory realistic level. In the middle of the description of a normal society there is a mention of the homeless living on dew-covered slopes in their tents. Who are these homeless? Nobody knows. Perhaps everything without a home in the world.

This is a very important element in her method. She glides back and forth between a mundane everyday and a poetic level, and forces the reader to accept this sliding. This element in her oeuvre is reminiscent of the works of Eva Ström.

Birgitta Lillpers’s poems are often long and epic. They continually reflect on the implications for a woman who speaks. Can language express her experiences? Is that desirable? How much is distorted? Many poems can be read as direct answers to critical objections to her poetry. She writes existential meta-poems; however, her thoughts are never abstract, but anchored in everyday objects and cares.

“And faced with reality there are suddenly no worn out / encyclopaedic volumes”, Birgitta Lillpers writes in Igenom: härute (1984; Through: Out Here). It is a line that describes her own manner of writing. What is real to her – and it sounds very specific – must be described distinctly, even truthfully. To write is always to reduce, but for the experience to contain its truth it must remain hard to decipher and complex, “so / that the pains are not distorted.”

When Birgitta Lillpers in Igenom: härute writes about a woman living in between two voices – one unforgiving and the other more liberating – she does not do so directly. Instead, it is conveyed through the humoristic story about the kinswoman who, in a basket under her ironing board, keeps the insufferable knämannen, a wooden figure that continually comments on her failings, and also a small group of tiny rescuers who eat sherbet and play joyous music. The rescuers know that truths are hard to come by.

Beauty could be a timeless morning, a

brittle leafing through of the undone from yesterday

and the reward is an early, strong, composed

sleep

quiet and small slices of bread, cinnamon, filled with

various types of corn and religions, that is

not the easiest to come by; the reward is that which is found sideways

with the opposition

and that is why we rescuers breed so

locally and exclusively.

The bold and fantastic imagery is characteristic of Birgitta Lillpers’s style. She creates images that incorporate entire imaginary worlds: about how it is “day after day staying alive in here, on the makeshift mint of wet-wipes” – Gry, och bärga (1986; Dawn, and Rescue) – or about the longing for a man who “dares to look right across my drawing table / and hold me a little by the lower arm when I fail / or when I don’t immediately understand the forms to be filled”, (Igenom: härute).

In Birgitta Lillpers’s poetic world, there is a basic opposition between the centre and the periphery, between speech and muteness.

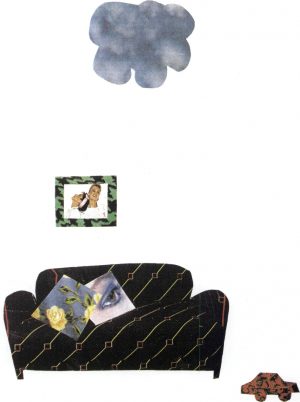

There are a multitude of allusions to folksongs, ballads, pop songs, the Bible, and older literature in Ann Jäderlund’s poetry collections. Here the reader finds influences from Petrarch, Carl Jonas Love Almqvist, and Edith Södergran. Of course this is a classicist trait, but in Ann Jäderlund’s case it is also a way of breaking with the modernist striving for originality. Time and again she stresses that literature and language is an echo chamber: I take what I want, I borrow from others. When Ann Jäderlund published the children’s book Ivans bok (1987; Ivan’s Book), it was no surprise that the illustrations were a collage of glossy magazine cuttings and other images.

And between male and female, as well. This basic polarity is the key to her lyrical work. She is often accused of being difficult, but if you read her from that perspective her poetic world opens up. Much that had seemed unclear falls into place.

At the centre are the “centre men”. They are not at all nasty, but enviably unconcerned. They are often childlike and self-righteous. They mostly listen to themselves. They do not know how to mourn their dead. They inhabit language as a matter of course. Outside are the women. They seem to live outside the world. They are small, often feel silly, and seem not to have any obvious place. They have no real language.

Most of what Birgitta Lillpers has written can be read as various paraphrases of this female isolation: “all the world is the secret / I alone / am not privy to”, reads a passage from Krigarna i den här provinsen (1992; “The Warriors in this Region”). The poems time and again repeat the experience of “not being understood”. This is described as terrible. The women live as if “wounded”: invisible, unseen. They often ask themselves “how is it worth living vulnerably”, I bett om vatten (1988; “Praying for Water”). They are in “a place where / no one else would endure”, Igenom: härute. But the question is where the women want to be. They are ambivalent. They feel mute in the world at large – and if they learn to speak the language of the world they feel that they betray something. “But”, as Birgitta Lillpers writes, “we also want a home with table cloths”, Igenom: härute. No matter how artistically visionary you are, you still long for a home with freshly laundered curtains and a well-stocked freezer.

What language does woman speak? In the poems, the women have to stick to what has been discarded by the men of the centre, to signs and words that they have abandoned. But that is not all bad. There, in limitation, they are forced to create something new. “When as so often there is nothing but left-over signs to stick to, / one must create a presence precisely for them”, Besök på en främmande kennel (1990; Visit to a Strange Kennel).

“Docentens hus” (“The Lecturer’s House”) is the title of a long suite in Gry, och bärga. It is an excellent example of how Lillpers’s imagination creates themes in her writings. The suite is a poetic and cheeky rewriting of women’s relationships to language and literature. It describes a house belonging to the lecturer. At the centre of the house is the lecturer’s work room (most likely with locked doors!) To this house come women from their snowy regions. They enter – through the kitchen door – into a kitchen where everything has been organised and cleaned, and faced with all this they lose their composure. Through the floorboards they hear the sounds of a radio, and it is immediately understood that something important that has to do with the Great World goes on in this house. It is “the sound that makes us yearn so nervously.”

As usual in Lillpers’s poetry, the men are not evil. The lecturer likes to offer avuncular advice: “you can learn to push discovery / but beyond / the extracted ascertainment / nothing exists.” The women can certainly try to push art, but they should not imagine that they can move beyond the territory men have already discovered. So when the women attempt to draw, the images do not come out as they want them to, but are filled by figures that resemble herons. In Birgitta Lillpers’s work, herons often stand for the original but useless.

In the second part of the suite, “Andra generationen” (“Second Generation”), the women have made a little progress. Now they are in the service corridor, which is a blatant metaphor for woman’s everyday position. A dinner is taking place in the dining room. The women – waiting among cakes, mousses, and fat fish – attempt to make themselves small and well-behaved. Their garments and shoes are really too small: “we tried to make our toes look like children’s toes.” All the while their expectant aim is the lecturer’s wonderful dinner.

But Birgitta Lillpers deepens the critique of today’s cultural isolation of the female. Ignominiously, some of these women slip into the dining hall – they are accepted into the male society. Remaining are the other crestfallen women who wonder why they are not also “harvesting love out there”. Again they attempt to remain true to something that keeps them from a place at the lecturer’s table. And again, the same suspicion: is this striving for authenticity worth the price?

The language used by Birgitta Lillpers seems to spring from a distant epoch. It is redolent with peculiar expressions and strongly archaic terms. It is a language that contains time. The words speak of old tricks of the trade – about working the fields, preserving, storing. Hay-drying on racks. Harvesting. Pickling fruit. In her poetry, these words are given a new and very positive valuation. They are slow and careful words that have been used far from all cities. They constitute a less exploited language.

Krigarna i den här provinsen was published in 1992. By then, Birgitta Lillpers’s style had changed. The poems have become clearer and tighter. They describe a desolate condition. Her landscape is now flatter; there are plains, expanses, and low fir trees, always exposed to a merciless sun. Here, hearts burn, she writes. Obviously, the collection can be read as a discussion of how unreasonable it is to send poems into the world. Behind the small warriors one senses a brave army of critics, even those who think they understand.

“Ynglingen” (The Youth) from Besök på en främmande kennel is a suite about meeting a young man. Initially, you think that it presents a new sort of masculinity in her poems: he is softer, more boyish, a half man. The woman teaches him to grieve and love. In a number of speeches, she gives him everything she has seen and understood from her isolation, “an infinitely vulnerable / knowing”.

Like Katarina Frostenson, Ann Jäderlund moves the language down into the body by letting the words speak directly to the senses. The poems are not “about”, they “bring forth” experiences.

The youth listens – and disappears. The suite can be read as a comment on men who annex the female. The young man has just made a brief visit to her region. He, who belongs in language, now goes fortified into life while she remains alone. “And I, / where shall I go now? There is / just one place where I can lay the quiet cloth / over life, / and it is akin / to that which is rejected.” So she is still there. Back in incomprehension. She is rejected. Without the grace of being understood.

With knowledge that still does not find a place.

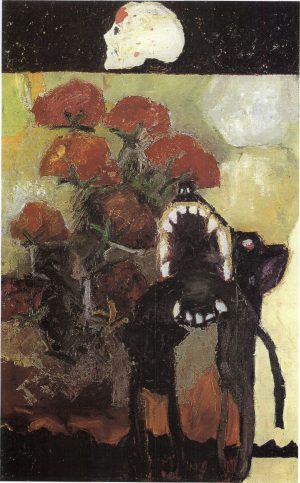

Helena Eriksson (born 1962) creates suggestive borderlands between animals and people. Whether the poetic speaker in the debut collection en byggnad åt mig (1990; a building for me) is human or not is hard to tell: she shakes out her scales, snarls, and tosses her bald head. There are violent meetings between her and the male you, “the animal king”. Around them exists a nature where everything falls, grows, and runs. It is clear that love and nature are something marshy, where you run the risk of sinking. It is, Helena Eriksson writes, “a place from which you will never find your way back”.

In Spott ur en änglamun (1993; Scorn from the Mouth of an Angel), the tone is lighter. With an entirely new purity and grace, Eriksson plays with light, air, and movement. The collection can be read as a female pastoral. In sunlit images girls in red silk dresses graze alongside animals in the hills, until one day they are lured by a fox. It is about female becoming, in a poetic rewrite.

Translated by Marthe Seiden