Swedish agriculture had a rough time of it in 1932, Axel Strindberg reminds us in Människor mellan krig (People between Wars). Many farmers went belly up, while the literary world was infected by a “summer holiday mood .[…] of corn shocks and devotees of life”. The thematic shift from ‘bread to corn’ among the young generation of proletarian authors strikes him as odd. Artur Lundkvist, Vilhelm Moberg, Ivar Lo-Johansson, Harry Martinson, and a number of other autodidacts wrote prose and poetry against the backdrop of the agricultural proletariat, with the sex drive playing the main role. At centre stage stood women and the soil, conflated in a single image whenever possible, to whom young men consecrated all their love and devotion.

Women authors weren’t slow to pick up the gauntlet. Among them were Ebba Lindqvist and other poets. Moa Martinson’s novels, Kvinnor och äppelträd (1933; Eng. tr. Women and Apple Trees) and Sallys söner (1934; Sally’s Sons) were published early on. Along with Moberg’s Mans kvinna (1933; Man’s Woman), they set the pace for a long list of fictional works about lawless passion in a rustic setting.

Moberg’s account of the relationship between a young farm wife and her neighbour in the 1790s became a formula that was restated in various ways, including in several 1930s novels by women, all of which followed a new trend that was referred to as primitivism or vitalism. The list consists of Av jord är du kommen (1935; Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Dust) by Gurli Hertzman-Ericson (1880-1954), Synden på Skruke (1937; Sin at Skruke), and Elida från Gårdar (1938; Elida from Gårdar) by Irja Browallius (1901-68), and Spelet på Härnevi (1938; The Game at Härnevi) by Berit Spong (1885-1970). Kvinnorna i släkten (1936; The Women of the Family) by Gertrud Lilja (1887-1984) may also deserve a place on the list. On the rare occasions that literary history alludes to these works, they are described as bucolic or peasant novels, a form of unfashionable realism. They have strains of naturalist fatalism, but also articulate a kind of female primitivism based on the trinity of woman, sex, and the earth. As opposed to Mans kvinna, in which the lovers escape to the forest to live happily ever after, the women in these books often pay with their lives for their forbidden passion. The novels formulate a more or less explicit critique of the way that patriarchal society links ownership of the earth to that of women as sexual objects while maintaining a level of erotic ambivalence – a strategy that successfully attracted wide female readership. One obvious source of inspiration was Elin Wagner’s tragedy, Åsa-Hanna (1918), about a crofter’s daughter who marries a shady merchant even though she loves the son of a poor neighbour.

Female primitivist literature was a hybrid between the peasant novel, modernist sexual romanticism, and the type of women’s novel that Gösta Berlings saga (1891; Eng. tr. The Story of Gösta Berling) perfected. Elisabeth Dohna’s feelings for Gösta illustrate Lagerlöf’s theme that women’s love must be unconscious in order to find favour and remain blameless according to the Law of the Father. Love that is conscious and actively covetous must be punished, as when Marianne Sinclair loses her beauty and begins to practise self-denial. Lagerlöf plays off “individual emancipation” against “Lutheran moral obligation”, creating the ambivalence so typical of women’s fiction. According to Horace Engdahl’s “En genial deklamation” (An Ingenious Recitation), “one purpose of this approach is to circumscribe and outmanoeuvre sexuality without sacrificing erotic tension. (Allt om böcker 2/92)

Erik Hjalmar Linder’s Fyra decennier av nittonhundratalet (1965; Four Decades of the Twentieth Century) classifies both Browallius and Martinson as ‘milieu realists’. With a couple of lines, he relegates Lilja (“occasionally intense”) to “the charming undergrowth of literature”, while omitting Hertzman-Ericson and Spong altogether. Nevertheless, Spong was a trailblazer of sorts. She melds an early form of erotic primitivism with meticulous descriptions of historical settings that may very well have inspired Mans kvinna. Even I Östergyllen (1928; In Östergyllen), her first book of short stories, has undeniable primitivist tendencies. “Min är den sjunde” (Mine Is the Seventh) in Kungsbuketten (1928; The Royal Bouquet) is a story of unbridled passion between forester Bjur and the half-vagrant Judeka in the bogs of Finnmark. The young farm wife in “Mellan Jul och Petter Katt” (Between Christmas and the First Day of Spring), from the same book, dies alongside her lover, a hired hand. And “Den röda källan” (The Red Well) graphically describes Midsummer’s Eve, which was still celebrated as a heathen fertility rite in rural eighteenth century Sweden.

Erik Hjalmar Linder, the same critic who extolled the stormy entrance of young male authors, demanded punctilious objectivity of women’s literature. In criticising Browallius’s higly erotic 1930s novels, which recount various transgressions of the Sixth Commandment, he asserted: “While intermarriage can lead to degenerate aberrations, literature that plays out against such a backdrop will lack universal appeal.”

Hjalmar regarded Browallius as “timeless”, though willing to concede that “she has found a new side to the peasant novel, which had appeared to be a depleted genre.”

But no critic or literary historian, not even Barbro Alving in her highly favourable study of Hertzman-Ericson, has made the obvious comparison between female primitivists and the male vitalists of the age. Alving calls Av jord är du kommen an “ode to rootedness […] a declaration of love for the land” in Swedish agrarian culture. She holds Hertzman-Ericson out as an eminent stylist, whereas Linder writes about Spong’s mastery of complex plot in Spelet på Härnevi and immediately reduces female literary skill to the “popular oral tradition” to which “the primitive storyteller” has always belonged – anciently primitive, in other words, rather than contemporarily primitivist. With such words, these authors are simply crossed off the list of modern literary innovators.

Generally speaking, female primitivists were more literate than their male counterparts. The novels reflect thoroughgoing knowledge of the joys and hardships associated with tilling the soil. They are a far cry from conveying the “summer holiday mood” that Axel Strindberg criticised in the works of young male authors. Nor do they skip over the role that women’s crafts – from sewing and food preparation to lace-making – played when it came to ensuring survival of the family farm. They also underline the central importance of women in making ends meet. It is hardly a coincidence that Browallius’s first story, “Selma är död” (Selma is Dead) from Vid byvägar och älgstigar (1934; By Country Lanes and Elk Trails), and Spong’s first story, “Till en hederlig begravning” (For an Honourable Burial) from I Östergyllen, are both about the death of a worn-out mother.

The female primitivists knew all about spic-and-span kitchens, filthy cowsheds, shabby farmhand’s quarters, and elegant vicarages, but did not flinch at burn-beating, potato fields, stables, and other outdoor settings. Browallius consistently employs Närke dialect in her dialogue, forging a stylistic register that ranges from irony (“The pastor’s family don’t even have pigs, do they?” – “Even if they did, it wouldn’t do them any good”) to heart-rending stupidity (“Why should I marry that one?” she thought, “or marry an old man when there are so many who want me?”). Spong’s style reflects a solid sense of history (a lover has eyes “whose colour resembles the smooth, dark bilberries that she had polished with the hem of her dress when she was a child before stringing them on a flax thread for a necklace.”). Hertzman-Ericson’s evocative imagery is more impressionistic (“The summer was as short as a tune on a birch-bark horn”).

Both male and female primitivists wrote about sexuality in a frank and open manner. But that is where the similarity ended. With a heavy dose of sexual Romanticism, men idealised the libido, giving full expression to the (male) individual’s scepticism of modern civilisation, including the emancipation of women. Meanwhile, women’s ambivalence about sexual pleasure that transgressed the Law of the Father drew inspiration from and expanded upon the earlier sentimental novels.

“Sins of Seduction”

The novels that Hildur Dixelius (1879-1969) wrote in the early 1920s about the pastor’s daughter and her forbidden passion forged a link between the literature that Selma Lagerlöf had brought to perfection and the new primitivism. Dixelius, who is generally omitted from literary history, started off with Barnet (1910; The Child), a very Platonic tale of infidelity that won first prize in a novel competition. She served as the flagship brand for the Åhlén & Åkerlund publishing house in the 1920s; her plethora of novels were printed in large editions and translated into German, Dutch, English, and French. She disappeared early from the Swedish scene after having married a German professor of philosophy and going to live with him. As anti-Nazi resisters, they later moved to Istanbul. In 1919, before leaving Sweden, she published a book about opera singer Signe Hebbe.

Prästdottern (1920; Eng. tr. The Minister’s Daughter), Prästdotterns son (1921; Eng. tr. The Son), and Sonsonen (1922; Eng. tr. The Grandson) take place in the provinces of Västerbotten and Ångermanland from the late 1790s to the mid-1800s. The first part of the trilogy makes particularly skilful use of an archaic style that now and then lends a documentary air to the narrative. The opening scene shows thin little Sara Alelia, a preacher’s wife in the Sami area of the Västerbotten province, laboriously printing a “scriptum” for the bishop. Her husband, who is a good deal older than she, suffers from paralysis, and when love enters her monotonous but God-fearing life in the guise of a young student, she gives herself to him as if he were manna from heaven: “I was like a stock dove in distress and an eagle came flying over the mountain.” She gets pregnant, is abandoned by her lover, and retreats to the isolated spot of Rombäckvallen where she starts a settlement and instils the fear of God in her son as a means of repenting for her youthful transgressions. The character of Sara is finely etched; she is the central figure in a tragedy that ultimately devours two more generations of her family.

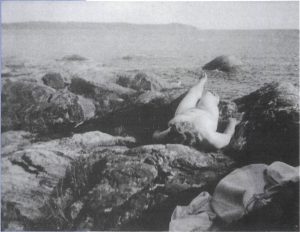

Male primitivist literature features women going for a swim. They paddle half-naked in “summer-dappled lakes” (Harry Martinson) or “let their ample breasts flow out of linen camisoles over the rushing water” (Vilhelm Moberg). Sara Alelia’s initial encounter with her beloved student provides an incentive for the erotic beach scenes of the 1930s:

“He arrived unexpectedly. Sara came up from the creek, where the maids were doing the summer wash. She had slipped on a footbridge and fallen into the water. She had her shoes and socks in her hands; her dark-striped, homemade cotton dress was wet all the way to her waist. The heat had caused her to untie her red silk scarf, which she was also carrying. And so they met as she made her way around the osiers along the ditch bank and up to the main road.”

One theme of the trilogy is the way that “sins of seduction” (sexual desire) always lead to disaster, culminating in Sara’s grandson – a fanatic pastor who turns out to have inherited the hot-bloodedness of his deceitful progenitor.

Sara keeps such a tight rein on her own desires that she almost drives Sahlén, the stoic schoolmaster who loves her to distraction, to an early grave. Like a reincarnation of Jane Eyre, she patiently awaits his ‘castration’. Half-blind and maimed, the Västerbotten version of Rochester gets her at last. The trilogy fully manifests the age-old dichotomy of women’s novels: desire is both washed to the surface and punished. The chastisement is mandated in higher quarters – God speaks through Sara, or so has she and her family come to believe.

Poetic justice is done when children who have been conceived in “sin” (forbidden pleasure) die. Lightning strikes the son of the fanatic pastor and his stepdaughter, and Fostersyskon (1924; Foster Siblings) recounts the death of a child who was conceived after a murder. The primitivists, who wrote a decade later, portrayed such children as hale and hearty, while their legitimate counterparts languish away. The primitivist, psychoanalytical gospel of instinct vanquished the old social morality, which had replaced sexual desire with privation and holy rapture. When Dixelius became more psychoanalytical in the 1930s, however, she did not write primitivist literature, but focused on accounts of neuroses, childhood traumas, and compulsive repetition.

Sexuality as the New Religion

Female primitivists constantly challenged the image of the earth as a compliant young woman that was propagated by their male contemporaries. They saw the role of the earth in patriarchal society as similar to that of female sexuality – both of them were always linked to and bound by an owner. The framework of their tales is the control of female fertility that the patriarchy has sought since time immemorial in order to ensure that the property owner would have legal heirs. The young heroines often stake their lives to circumvent the law. Spong’s Spelet på Härnevi starts off with what appears to be a semi-confession by the dying wife of a propertied farmer that he is not the father of their daughter, the heiress to his estate. The deathbed murmurings trigger a fateful tragedy that ends with the suicide of the daughter when she concludes that the farmhand she is in love with must be her half-brother. But her real crime is that she breaks her engagement with the son of a rich farmer to be with her landless lover. Thus, the primitivists resemble Dixelius in that unbridled passion serves as a subversive force that takes its revenge in the second or third generation. But there is an obvious difference between the two genres. The new doctrine of instinct that had taken the place of the patriarchal religion that demanded women’s submissiveness paved the way for a language that could finally describe their sexual needs. Meanwhile, it presented legally sanctioned sexuality as a painful duty and marriage as a relic of antiquity.

The love scene in which a farmer’s daughter gives herself to the farmhand before finding out that he may be her half-brother is the high point of Spong’s Spelet på Härnevi:

“She immediately noticed a change in his tone and in his touch, and it made her calm and inwardly grave… Play and small talk, jealousy and affectionate coquettishness yielded and fell away like sepal that had done its duty, and desire flared up, furiously like a poppy in the field and just as red in all its simplicity. They closed their eyes, and still they saw each other; they saw each other with their hands and with their skin, which was dampened by the perspiration of love and cooled by the shivers of passion, and they spoke each other’s names and thought they had said all there was to say. But trying to hold back his final intoxication, he bit her on the neck, off to the side where her hair fell down and grazed his mouth; and she long sported impressions of his sparse teeth, two small wounds, connected by a dotted red line where blood had burst forth under her skin. She didn’t show that she felt it, but he had the taste of blood on his lips and came to his senses.”

Spong followed up on her long novel Nävervisan (1942; The Birch-Bark Ballad) with a sequel, Svarta tavlan (1946; The Blackboard). Like Lyttkens’s 1940s novels of emancipation about the Gustavian Tollman family, Spong documents a feminist version of social mobility. Her books, which take place between the Romantic period and early modernity, made it eminently clear that primitivism was on the wane as a literary movement: Ann-Lovis, the heroine, gets the man she loves and still holds onto her career as the first female elementary school teacher in the district. The title of Nävervisan is an allusion to Swedish hymn 325, which is said to have been written in the seventeenth century on a piece of birch-bark by Elle Andersdatter, the young wife of a Danish burgher. The book lends the female tradition the quality of a supernatural game where superstition plays into the hands of emancipation.

Spong’s key novel Sjövinkel (1949; Sea Angle) caused a scandal through its account of the trials and tribulations that she and her husband endured as headmistress and headmaster in Strängnäs, lashing out at the narrow-mindedness and ingrained distrust of intellectuals that characterised small-town Sweden.

No longer the pioneering primitivist of the 1920s and 1930s, she was writing banal love stories by the late 1950s. Her late novels, Ingen sommarhimmel (1957; No Summer Sky) and Under svart vimpel (Under a Black Pennant), depict the aristocratic officer class in Germany just before the turn of the century. Their message is that a woman should obey her husband no matter how dubious his honour.

Browallius, also a teacher, took another route in her post-primitivism period. At the end of her prolific career, she was writing semi-documentary novels about contemporary issues, such as modernisation of the countryside – Ut ur lustgården (1963; Out of the Garden of Eden) – or the foster child system – Skur på gröna knoppar (1965; Shower on Green Buds) and Instängd (1967; Shut In).

Sophie von Knorring (1797-1848), who published the first novel of the Swedish countryside, Torparen och hans omgifning – en skildring ur folklifvet (1843; The Cropper and his Surroundings – a Chronicle from the Life of the People; Eng. tr. The Peasant and his Landlord; or, Life in Sweden), was the forerunner of female primitivism. As with Spong and Browallius, whose historical narratives were influenced by ideas about women’s emancipation, Carl Jonas Love Almqvist’s Det går an (1838; It Can Be Done; Eng. tr. Sara Videbeck and the Chapel) was a sine qua non for Knorring’s book.

Lust for the Earth

Her more distinctly primitivist novels, Synden på Skruke and Elida från Gårdar, present sexual passion as a violation of agrarian social norms. As opposed to Spong, Browallius confines herself to a contemporary setting: “’Haven’t you read about Hitler and Musselinee and the commonists?’ he asks accusingly. ‘They are the Antichrist, let me tell you, in three forms.’”

Efriam, a small farmer in Synden på Skruke, lusts after Hilda of Guttersbo, his poor but hot-blooded neighbour, bringing down a curse that plagues Skruke for three or four generations, including his children with Lisen, his faithful and trustworthy wife. In a paroxysm of machismo, Efriam gets both Lisen and Hilda pregnant, but receives his comeuppance when Lisen’s frail son dies while Hilda’s (the “wild seed”) flourishes. Lisen takes revenge by seeing to it that her daughter Agnes does not marry the farmhand she is in love with.

“Finally Hilda was in front, and Efraim walked behind. Now he knew what it was all about. He grew serious, pursued her like a bull elk in the autumn […]. As he followed, he watched her swaying hips and white neck where her hair had curled beneath her blouse. The room seemed to swim before his eyes when he understood what has about to happen. Not a word was exchanged. Two silent shadows glided among the young spruce trees. Suddenly they emerged from the forest; the trail had ended […]. Hilda still led the way. Desire propelled her. Winter was over, and the heat was returning to her blood, enticing and guiding her. Efraim was, after all, a big, strong man with iron fists and money in the bank.” (Synden på Skruke).

Elida från gårdar, a primitivist escalation of Wägner’s Åsa-Hanna (1918), introduces us to the beautiful ragbag Stamp-Elida toiling in the fields. She avariciously imbibes the acrid air, a sure indication that she is a sensuous creature doomed to adversity. But her uncommitted relationship with Linus, who works at the sawmill, is not her downfall – Browallius presents it as egalitarian and natural: “She put her arm around his neck, and he felt the coolness of her skin against his cheek. Both of them sighed resignedly. They couldn’t resist their desire for each other any longer. Elida surrendered willingly to his power and received his love artlessly and unaffectedly. She never had any misgivings or questioned their relationship.” Certainly she wants to marry up in order to escape the drudgery of the agricultural proletariat. After she weds a merchant, Linus goes away to train as a forest warden. When he re-enters her life like Thomas Mellor in D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928), things quickly go downhill. She still loves him, but she cannot let go of her bond to the land. She starts to fantasise about doing away with her husband and running the farm with Linus by her side, but that disgusts him, and he takes off again. Pregnant with Linus’s child, Elida murders her husband, sets the farm on fire, and dies in the flames. At that point, the wind changes direction and spares the rest of the village, which the neighbours interpret as a judgment from on high.

Gurli Hertzman-Ericson, the daughter of a wealthy merchant from a family of industrialists, started off with a collection of folk tales entitled Från mor till barn (1903; From Mother to Child). She was a free-thinking intellectual who worked as an editor at Rösträtt för kvinnor (Women’s Suffrage) in the 1910s and wrote two novels with social themes – De stumma legionerna (1918; The Mute Legions) and Trotsiga viljor (1920; Defiant Wills) – before her first popular success, Huset med vindskuporna (1923; The House with the Dormer Windows), a collective novel. The anti-Nazi novels that she published during World War II provided solid entertainment in a context of human solidarity and ethics. Av jord är du kommen fully and unexpectedly manifests the fundamental concept of primitivism. The master of the highly esteemed Danielsgården farm is beset by uncontrollable desire for Elma, the sensual wife of his neighbour, and eventually pays for it with his life. As in Synden på Skruke and Spelet på Härnevi, his legitimate daughter Jonna suffers the consequences. Just as her counterparts in the writings of Browallius and Spong, she is obsessed with ownership of land and property. She is forced to sacrifice her lover but dies happily with his cheek against hers after rescuing his little daughter from drowning. Domaredansen (1941; The Judge’s Dance) downplays the theme of primitivism in favour of emancipation. Christina Jon Pers leaves her son with his father, who is too cowardly to marry her.

That even Gertrud Lilja was influenced by primitivism demonstrates the strength of the trend. Kvinnorna i släkten, which takes place in the province of Småland at the turn of the twentieth century, finds Johan – a lay assessor’s son who has been married off to Kristina, the stately but sexually inhibited daughter of a farmer – lusting after his neighbour Mari. Lilja started off in 1924 and was a traditional prosaist who called her favourite theme – that men always choose the wrong woman, which drives the right woman crazy – a universal problem.

“Kristina was seized by violent hatred for Mari and all women of her type whose bodies were weak and whose souls were willing, who weren’t ashamed of their desires, who had not been born with bashfulness that stiffened their limbs and hardened their features […]. She looked at Johan again. He breathed calmly, smiled a little in his sleep – perhaps he was already sober, it didn’t take long with him. She felt his leg against her leg, his hip grazed hers […] She longed suddenly for him to wake up.

Overcome with shame, she moved farther away, buried her head in the pillow, and burst into tears.”

Kvinnorna i släkten

The portrayal by female primitivists of the libido as both amoral and natural represents an evolution of the moralistic ambivalence that Maria Sandel had evinced at the beginning of the century. Sandel’s last novel, Mannen som reste sig (1927; The Man Who Rose Again), describes the repellent/attractive qualities of Ulla, a slatternly woman who drives her upright husband to ruin. Female primitivism decoupled the ambivalence of the sentimental literary tradition from its religious, patriarchal assumptions and turned it into a sensual code that stood on its own. The erotic undercurrent of female sexuality contributed an extra, masochistic sense of satisfaction, as if transgressing the Law of the Father elevated lust to ecstasy. Female desire in these books burns down villages, devastates marriages, slaughters farmers, and allows women to affirm themselves by listening to their bodies. Eventually, they and their offspring are punished mercilessly, often with death.

Translated by Ken Schubert