The year 1909 is as good a focal point as any. A general strike was under way in Sweden and women were fighting for the right to vote. Two of them were in the limelight that December. Ellen Key was honoured on her sixtieth birthday, while Selma Lagerlöf became the first woman and the first Swede to win a Nobel Prize in Literature. Earlier in the year, a Swedish reporter had stood outside the gates of Holloway Women’s Prison in London. A group of suffragettes was about to be released.

Women held their own Nobel Banquet for Selma Lagerlöf at the Grand Hotel in Stockholm on 13 December 1909. Some twelve hundred guests were in attendance, while more than one thousand had been turned away. Both Swedish and foreign newspapers provided extensive coverage. The keynote speech, delivered by Lydia Wahlström, was entitled “Every Woman’s Gratitude.” Lagerlöf responded by having Fredrika Bremer make an appearance and witness the multitude of prominent, capable women.

Culmination and beginning. Key and Lagerlöf had conquered the world, each in her own way. The female strikers found their mouthpiece in a novel by Maria Sandel (1870-1927) entitled Virveln (1913; The Vortex). Elin Wägner, the reporter outside the prison, was in London to cover “the greatest movement the world has ever seen”, the Fourth Congress of the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance.

“An Authoritative but Insufficiently Trained Speaker”

When Key mounted the platform in 1883, it must have been seen as both a frightening and bewildering sign. The general public had still not grown accustomed to suffragettes on lecture tours. Key was a pioneer in the field – “an authoritative but insufficiently trained speaker,” as Carl David af Wirsén described her. It started off unpretentiously enough. Fifteen people showed up to hear her at the Swedish Workers’ Institute in the Kungsholmen district of Stockholm. Before long her pulpit was smack dab in the middle of Europe, and she was called “The Great Aunt of Europe”.

The most cherished member of her inner circle was Lou Andreas-Salomé, with whom she corresponded for over a quarter of a century. She hobnobbed with nearly “everyone who mattered” in pre-war Europe: anarchist Pjotr Kropotkin, sculptor Auguste Rodin, playwright Gerhard Hauptmann, philosopher Martin Buber, dancer Isadora Duncan, and poets Rainer Maria Rilke and Maurice Maeterlinck. Key’s word was often law. Her verdict could elevate or destroy a young writer.

Andreas-Salomé sketched a touching portrait of Key in 1905. Key was visiting Andreas-Salomé at Loufried, her home on the outskirts of Göttingen. Shortly before leaving, she removed her dress to have it brushed off. So there she was, sitting at the breakfast table in her green, loose-fitting knickers. “And floating above it all,” wrote her hostess, “was an affable, earnest face – Ellen Key in a nutshell.”

Her medium was speech; she generally presented a thought in a lecture before formalising it in an essay. Lagerlöf took the opposite approach. Her element was the printed page – “This writing, my dear, is my only passion.” If she took to the rostrum, she was sure to have a tale or two in hand, ready to enchant even the most callous audience. One of her challenges was to effectively champion social causes without sacrificing her distinctive mode of analysis and expression.

World War I brought the issue of Lagerlöf’s mode of expression to a head. The world was waiting for her pronouncement. What would she have to say when confronted by the reality of the conflict? And how explicit, how propagandistic, could she be? The novel Bannlyst (1918; Excommunicated; Eng. tr. The Outcast) was her answer after years of hesitation and writer’s cramp. The book was a call for peace, though both subtle and original. Built into the novel is the theme of the peculiar female voice that must establish its authority without abandoning its singular position on the periphery. The theme reaches its climax towards the end of the book. A woman’s voice is heard during a sermon by the local pastor. The voice is “thin and shrill”, as it has been throughout the story. But now it is also “strangely audible and distinct”. The voice,

Vocal Chords under the Spell of Women’s Suffrage

twenty-seven-year-old Elin Wägner had just been recruited to the women’s suffrage movement. She would rewrite both Lagerlöf and Key, borrowing key themes from each of them.

Wägner published her article on the release of the suffragettes from Holloway in the May 1909 issue of Idun:

“[…] accompanied by shouts of joy, the prisoners dashed out, happy if a bit pale, to be embraced by their friends. The leaders were there, and I could observe Miss Pankhurst close up. She looked like a clever, well-behaved schoolgirl. And yet she’s the one who constantly stirs up trouble and has been called the Portia of the suffragettes due to her eloquence.”

In the case of Key, she took the burning topic of how to define women’s nature and the relations between the sexes.

Wägner was the most indefatigable opponent of the Swedish patriarchy for four decades. Her first memorable work was Pennskaftet (1910; Eng. tr. Penwoman), a novel that takes place in Stockholm and became a bible for “the new woman”, who is also referred to as the “self-supporting educated woman.” Two of the central characters, Cecilia (the woman with a past) and the Penholder, reflect Wägner’s own life.

An article by Aleksandra Kollontai entitled “Novaya zhenshchina” (The New Woman) that appeared in Sovremennyi Mir (The Contemporary World) in 1913 asked rhetorically:

“Who is she – who is the new woman? Look around, strain your eyes, examine your five senses, and you will be convinced that the new woman is here – that she exists.” According to Kollontai, a subconscious set of criteria had recently developed with which different types of women could be distinguished from one another.

Cecilia is swooped up at the beginning of the book by Ester Henning, a captivating but strong-minded suffragette. Before long she meets the “Beasts of Burden”, the diverse nucleus of hardened activists on Lästmakaregatan street in Stockholm. The suffragettes in Pennskaftet are Wägner’s own creations. But they are based on women who will always be linked to the Association for Women’s Suffrage (FKPR), founded in 1902, later the National Association for Women’s Franchise (LKPR). The list includes Professor Ann-Margret Holmgren, the orator who led the movement, historian and director of studies Lydia Wahlström, who became the Chairwoman in 1909, Deputy Chairwoman Signe Bergman, a bank cashier, the mild-mannered but unflinching “mother of women’s suffrage”, school founder Anna Whitlock, social reformer Anna Lindhagen, the broad-minded Emilia Broomé, and factory inspector Kerstin Hesselgren.

The book captures the full panorama of the new woman’s life in the big city: safety, transport, dress, career, menstrual cramps, housing, diet – and, above all, sex. The most incandescent theme of the book is the need for “the new man”.

Pennskaftet is about the semiotics of the new woman and the new eroticism. A new system of signs has emerged. Women hurry home when the trams are no longer running, go to a restaurant to catch a bite to eat, or talk with a male co-worker. Modern society comprises all such signs, but few people are able to interpret them. Architect Dick Block, a young and not wholly unsympathetic man, steps in to fill the gap. He is the faltering coming-of-age hero, bearer of the requisite decoding and recoding of vision.

The novel’s hidden agenda is to find a way of turning “man as he is” into “the new man”, a worthy partner for the full-fledged new woman. At the beginning, Dick

Even the reader has to wipe away a tear or two. From now on, “woman” represents independence, efficiency, diversity, loyalty, sensuality, and articulateness. One way of viewing the new woman is as a lover finds her on a summer morning: “in bed with a women’s suffrage button on her nightgown, writing under a parasol while the curtains flap like taut sails.”

Crafting Modern Swedish

With Pennskaftet, female journalists came into their own as literary figures. Actually they were already a force to reckon with. Klara Johanson, recruited from the Fredrika Bremer Association magazine Dagny, had started as a reviewer and columnist for the Stockholms Dagblad newspaper back in 1899. Among the other bright new journalists were Marika Stiernstedt, Anna Stina Rydell Alkman, Elin Henriques Brandeli, Else Kleen (Dagens Nyheter), and Hedvig af Petersens (Aftonbladet).

They rather than the bourgeois realists and flaneurs were the people, who crafted modern Swedish. An article by journalist and writer Staffan Tjerneld entitled “The Women of 1918” praised the freshness and originality of the language employed by female reporters and novelists compared with that of the male notables of the age. He was referring to Wägner and her Kvarteret Oron (1918; The Anxiety District), the only story of the profiteering period during World War I that remains relevant. Another journalist whom he had in mind was Marika Stiernstedt and her wartime reporting, published as Från Frankrike fjärde krigsåret (1918; From France in the Fourth Year of the War). Then there was Agnes von Krusenstjerna and her portrayal of the decline of the Swedish bourgeoisie in Helenas första kärlek (1918; Helena’s First Love). And finally he was referring to Ulla Bjerne, the unjustly forgotten representative of la bohème and the new woman. Bjerne’s Dårarnes väg (1918; Path of Fools) was based on her experiences and observations in Paris and Senlis just before the war. Born and raised in the town of Söderhamn, she wore men’s clothes, was painter Nils Dardel’s “lady in the green pyjamas”, took Gustaf Hellström as her lover to learn how to write novels, and smoked and drank with swashbucklers like Henning Berger and Frank Heller. Bjerne’s pre-war novels Mitt andra jag (1916; My Other Self), and Dårarnes väg present the new woman in her cosmopolitan and ominous incarnation, surrounded by absinthe, cocaine, and the white slave trade.

But consummate journalists had already made their mark

Ester Blenda Nordström, a friend of Wägner and her husband John Landquist, had been a Stockholm journalist since 1911. In 1915, she took a job as a roaming school teacher in Lapland. She documented her life with the Sami in Kåtornas folk (1916; People of the Tents; Eng. tr. Tent Folk of the Far North). She also published Amerikanskt: som emigrant till America (1923; American: as an Emigrant to America) based on her experiences as a stowaway and waitress in the New World. Her last chronicle, Byn i vulkanens skugga (1930; The Town in the Shadow of the Volcano), is about life in Kamchatka.

A chapter entitled “Tintomara” in Landquist’s book I ungdomen (1957; In Our Youth) recounts:

“Ester admired Elin both as a journalist and a writer. We looked at her as Elin’s first pupil, particularly when it came to the column-writing style that Elin introduced.”

Voices from the crowd

Wägner’s first novel Norrtullsligan (1908; The Nortull Gang) also involved a kind of participatory journalism. The book revolves around the growing ranks of women clerks whose fate she shared as a boarder in various rooms around Stockholm. Another type of documentary, the diary of a prostitute, had received widespread attention the year before; it was entitled Den undre världen (The Underworld). The author was Anna Mathilda Cecilia Johannesdotter Johansson (1877-1906), and the publisher was cultural journalist Klara Johanson.

Sandel lent her voice to still another disadvantaged group: industrial working class women. Considering Sandel’s proletarian background and the new material she presented, her mastery of artistic expression is truly amazing. Her prowess is particularly evident when it comes to dialogue and the ability to choose situations that capture the essence of the people and living conditions she describes.

The use of melodramatic and dime novel techniques in her social realism was both pioneering and the source of great suspicion. A woman wearing a white veil embraces a man in a moonlit churchyard. A seamstress on her way to another arduous night witnesses the episode. Suddenly she realises that the woman is a young baker in the neighbourhood and the man is her own fiancé.

The first issue of the Social Democratic women’s newspaper Morgonbris (Morning Breeze) appeared in November 1904. The publisher was the Women’s Trade Union. The name, suggested by Maria Sandel, was taken from a poem by Hjalmar Gustafsson of the Social Democratic Youth Federation. The final stanza goes:

“For we greet you – young,

Fresh, and daring morning breeze.

May you lead us from snow and ice

To freedom, sun, and song.”

The writings of Anna Lenah Elgström (1884-1968) also elicited voices from the deep, Dostoevskian in its essence, suffused like never before with the yearning and suffering of the soul. A history of Swedish prose free from male preconceptions would point to Elgström rather than Pär Lagerkvist as the pioneer of expressionism and anxiety-ridden soul-searching. Her short story collection Gäster och främlingar (1911; Guests and Strangers) preceded Lagerkvist’s Människor (1912; People).

Ellen Michelsen wrote about Kristina Erbrecht, a Salvationist in Elgströms first book Gäster och främlingar, for Volume 2 (1920) of the Danish cultural monthly Tilskueren:

“She does her duty in the plague-smitten, foetid dens of iniquity. She kisses horrid prostitutes if only they ask her to. Not out of Christian piety, but impelled by her prodigious compassion, her love for these poor creatures, so brutally abused by fate. Like a sentry in the night, she stands at the window of the Salvation Army shelter and gazes into the depths of the Old City. Make no mistake about it, she is holding someone to account. And she hurls her weary, bitter Why into the emptiness of space, towards the silent stars.”

“The Pain of Millions was Given a Voice”

The outbreak of World War I was cataclysmic, perhaps more for these newly liberated women with their revolutionary visions than for anyone else. Key wrote to Andreas-Salomé: “Alas, my dear Lou, will not all the golden bridges that the peoples of the world have constructed be washed away in blood and fury?” (30 September 1914).

None of the women fell silent, but their idealism lost some of its sheen. Lagerlöf wrote Bannlyst, a farewell to the aesthetic that had animated her earlier. Key turned into the dark and misanthropic “Sibyl of Strand”, light years from the herald of joy and happiness. Wägner used an international women’s suffrage congress to symbolise her disillusionment. The story is ironically entitled “De eniga millionerna” (Millions United). The dream of international solidarity goes up in smoke, and the congress scatters like a beehive that has been set on fire when a telegram arrives that war has broken out.

In reality, however, the movement regrouped. The Congress of the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance scheduled for Berlin

Citizens with Power and Authority

The women’s suffrage movement had long aroused opposition from conservative forces and the military establishment. Men were now Sweden’s most valuable possession. A right-wing brochure urged women to “sacrifice your selfish little cause for the greater good of your country.” Imagine, wrote Wägner, putting the interests of your country above your pride as a woman. Nevertheless, many women believed as early as 1906 that victory was at hand. But 1907-1909 saw only a small step forward – women became eligible for election to municipal assemblies. Universal suffrage and eligibility for office did not become a reality until 1921.

Elisabeth Tamm, a landowner in Julita, was among those who were elected to municipal office following the first reform.

She was also one of the five members of her sex elected to the Riksdag in 1921. The Association of Liberal Women (FFK) reconstituted itself as the National Federation of Liberal Women that October at Tamm’s estate in Fogelstad. The objective was to prepare women to exercise their newly acquired power.

Five activists, later referred to as the “Fogelstad core group”, attended the meeting: Tamm, Wägner, Ada Nilsson, Kerstin Hesselgren, and Honorine Hermelin. The effort quickly expanded and turned out to be one of the most meaningful, original, and forward-looking developments of the inter-war period.

The first “Basic Course in Civil Rights” was held at Fogelstad in the summer of 1922. Two or three FFK representatives from each province were invited to attend. In 1925 the initiative was institutionalised as the Women´ s College for Civic Training at Fogelstad, which admitted students regardless of social class or political persuasion. Hermelin served as headmistress until the school was disbanded in 1954. Its main goal was to explore the relationship between the public sphere and personal life. Women’s unique experience was viewed as an important asset for political renewal. Among the teaching aids were a make-believe rural municipality called Komtemåtta, with a church, agricultural community, brickworks, orphanage, doctor’s residence, and other amenities. Students learned the ins and outs of exercising political and economic power at the local level. A fundamental maxim of the school was the commonality of hand, brain, and heart – no theory without practice, and no political action without considering the dictates of sensibility and emotion. Fogelstad proved unusually successful in breaking down social barriers and recruiting students from all classes.

Martinson recalled her participation in the spring 1928 course at Fogelstad:

“New layers of my brain were suddenly put to use. Everything I had read about and learned on the croft proved valuable. The others were sympathetic to what I had to say […]. There were large gaps, both literary and academic, in my upbringing. But the knowledge of the educated women also fell short when it came to society and ordinary people, so we were even.”

Jag möter en diktare (1950; I Meet a Poet).

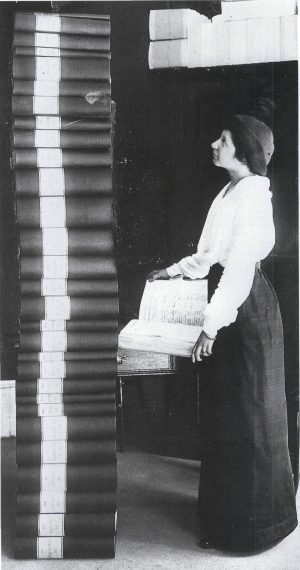

The core group, which eventually included attorney Eva Andrén and physician Andrea Andreen, also published a magazine entitled Tidevarvet. The first issue appeared on 23 November 1923. The magazine, which served as a vehicle for all kinds of ideas until it folded in 1936, could boast of superior journalism.

As editor-in-chief of Tidevarvet, Wägner wrote to her friend Ingeborg Björklund, a poet:

“It might not have been such a big deal to put together a little magazine, but when you have to write it as well and be your own maker-up, copy editor, errand girl, and typist, you’ve got your hands full.”

(24 July 1924)

Wägner was the editor-in-chief from 1924 to 1927. The office started off at printing works in a dimly lit cellar on Vattugatan Street in Stockholm and later moved to a bright flat on Triewaldsgränd Lane across from the consulting rooms of Dr Ada Nilsson, the publisher. Circulation peaked at a modest three thousand subscribers.

Barbro Alving wrote to Hesselgren in 1954: “Was there ever an uneventful day at Tidevarvet?” Hesselgren replied: “I think not.”

The Inner Voice

Klara Johanson wrote some of the most scathing articles in Tidevarvet. In November 1923-December 1924 and January 1932-May 1933, she contributed brilliant (albeit a little too astute for many people’s taste) “Observations”. Many of her pieces invoked Frederika Bremer to address the burning topics of the day.

Among them were “The Inner Voice” (no. 6, 1924). Women’s suffrage was a fait accompli, Johansson started off. But what good was it if women were no more than what Sophie Adlersparre prophetically referred to as “the errand girls of the political parties”? Bremer issued another proclamation: “Behold the handmaid of the Lord!” That does not mean subservience, but women’s declaration of independence: Handmaid of the Lord, not of their lords. Women had to start listening to their inner voice. In order to do so, they must “politely but firmly resign their position in society as domestic servants.”

Obey not your masters, but a higher authority. Nowhere did that authority speak more clearly than when it came to peace and the Earth. The masters had failed to establish peace either on or with the Earth. Who could change the sorry state of things if not women? The interests of women, the Earth, and peace were inextricably linked. Most feminists of the interwar period found common cause in that trinity of concerns. Among their accoutrements was a fundamental ecological perspective, which showed up as early as in Lagerlöf’s Gösta Berlings saga (1891; Eng. tr. The Story of Gösta Berling). Tamm was the Riksdag’s theoretician and advocate for ecological issues. Thus the philanthropist of Fogelstad joined forces with Lagerlöf, the farmer from Mårbacka. The holistic approach brought together Key, the ageing health oracle of Strand, Wägner, the part-time farmer of Lilla Björka, and the crofter Moa Martinson. The overpopulation issue, on which Ada Nilsson served as an expert, was integral to their analysis. Even the literary elite – Johanson, Emilia Fogelklou, Agnes von Krusenstjerna, and Karin Boye – was on their side.

A number of seminal books were shuttled back and forth between Wägner and Fogelklou in 1938. The most important of them was Johann Jakob Bachofen’s Das Mutterrecht (1861; Eng. tr. Mother Right). Among the others were Jane Harrison’s Themis (1912), an interpretation of Greek mythology and its testimony to an ancient matriarchal society; Albrecht Dietrich’s Mutter Erde (1905; Mother Earth); and Sir James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (1890).

Wägner became engrossed in such studies after returning from a trip to Greece in 1937. Their biggest discovery was the falsification of history. What had happened to all the “signs” of another time, of other possibilities? Pennskaftet had sought an alphabet for the “new woman”: The quest now was to

Women’s Suffrage, Humbug!

Wägner’s Väckarklocka (1941; Alarm Clock) took on that task of decoding and recoding, sometimes in direct contradiction to Pennskaftet. “What has women’s suffrage accomplished?” was one of the underlying questions. “Still plodding along in men’s tracks”, came the answer. Only if women deciphered the code, read the signs properly, and reconstructed the half obliterated traces of the ancient past could they find their way back to ways of life that affirmed propagation, nurture, and growth.

Back in the nineteenth century, Bachofen had discovered one such sign: the opening of Aeschylus’ Eumenides, the final play in the Oresteian Trilogy. The play opens with an invocation, as the priestess reviews the line of succession at Apollo’s temple in Delphi. The first three keepers were goddesses: Gaia, Themis, and Phoebe. Apollo is a trespasser – a python-killer and distorter of signs.

Wägner experienced another sign in her personal life. She was standing at Cape Sounion, the place from which Aegeus had once watched for his son Theseus’ return. Would the ship bear a white or a black sail? As it turned out, the sign was misleading – the sail was black even though Theseus had triumphed. What Wägner realised is that the ‘error’ carried a meaning. It was hardly conceivable that a hero would simply have forgotten to announce his victory.

No, the sign represented the true import of his victory, the conquest of the matriarchy. With the assistance of Ariadne, he had slain the Minotaur of Crete. But he broke his pact with her and left her on Naxos. The black sail symbolises his inner conviction that the betrayal was a loss, the victory a bereavement. The patriarchy – along with its lust for conquest, its monuments, pageants, processions, and other tokens of power – was now here to stay.

Wägner’s Väckarklocka is just as desolate as Lagerlöf’s Bannlyst. In both books, the war is already raging and the only salvation is to take stock of the most fundamental, deeply buried resources, ultimately in the custody of the Mother. Not the mystical, preconscious, opaque, elemental substance, but its visionary, lucid, and enlightened essence. Listen closely, the authors seem to be saying, and you will hear the voice that we all bear within us.

According to Wägner, a “pole shift” in prehistoric times from matriarchy to patriarchy created a new symbolic language and way of looking at the world. The “experience of the warrior” became the foundation of science (domination of nature) and the general attitude towards life (Darwinism’s survival of the fittest). The Big Bang Theory is a modern example. “If I take a walk in the forest, I have to remember that the peace I experience is only a mirage. The trees are engaged in a furious battle for light, space, and soil nutrients.”

(Väckarklocka)

Translated by Ken Schubert