The salon culture pursued by Friederike Brun and Charlotte Schimmelmann in Copenhagen mansions and houses in the countryside at the beginning of the century lost its base and its future along with the national bankruptcy of 1813. Denmark was impoverished; now economies had to be made both in public and private funds. A well-reputed academic and budding writer such as Johan Ludvig Heiberg (1791-1860) had difficulties getting a job. He thus launched the journal Kjøbenhavns flyvende Post (1827-37; Copenhagen’s Flying Post) in order to make a living; two articles from his own pen, “Om den i det offentlige Liv herskende Tone” (1828; About the Prevailing Tone in Public Life) and “Om vore nationale Forlystelser” (1830; About Our National Amusements), tell us a great deal about the milieu in which women’s literature of the Romantic era originated. With straightforward observations of mealtime procedures, outings to the woods, consumer patterns, and trips to the theatre and to restaurants, he paints a picture of traditions and bad habits in the domestic lives and public comportment of Copenhageners – his intention being to enhance their discernment.

We have the word of writer Benedicte Arnesen-Kall (1813-1895) that the ‘flying post’ appealed to the middle class:

“For me it ushered in a new world and sowed the first seeds of interests and attitudes that were later to have no small impact on my life.”

Livserindringer (1889; Memories of My Life).

At the same time, Heiberg wrote a number of vaudevilles which were great successes at the Royal Danish Theatre: Kong Salomon og Jørgen Hattemager (1825; King Solomon and George the Hatter), Aprilsnarrene (1826; April Fools), Recensenten og Dyret (1826; The Reviewer and the Animal), and the national treasure Elverhøi (1828; Elves’ Hill); in 1829 he was therefore accorded the title of ‘theatre poet’. In 1830 he was appointed professor at the Royal Military College. He thus represented the new middle class, consisting of public officials and merchants; these people were now the culture-bearers and they also, with the fall of absolute monarchy in 1848, took over political power. Vaudevilles and articles about the daily lives of Copenhageners presented Heiberg’s various suggestions for ways in which to shape a culture for this new and influential class.

The main thrust of the articles is that the middle class lacks identity. In Heiberg’s opinion, having taken on its cultural benchmarks from the aristocracy without having the financial resources to live up to them, the middle class is, for all practical intents and purposes, totally devoid of standards. As an example of the disparity between ideals and realities, Heiberg mentions the old tradition of fitting out the best room in the house as a “hall”, a room solely designed for large evening parties with supper and dancing: “although many families are in the position that they hardly hold one large party a year, they nonetheless consider ‘a hall’ to be almost inseparable from domestic happiness.”

He wanted to teach the women to organise life at home in such a way that there was time and space for the important things – exchange of ideas, intercourse of the mind – keeping at bay all that causes ‘indolence of the soul’.

Heiberg wants the salon culture of the previous generation to be replaced by an intimate sphere. The expensive representative façade, with a single lavish party when the occasion arose and an otherwise impoverished daily life, should be superseded by “the correct middle way”, in which quiet speech, simplicity, order, and “the ability to have one’s body under control” should be the hallmarks of family life, both when the family is alone at home and when there are guests. Any social gathering should be neither “too big nor too small”, it should comprise people “who by way of a similar degree of education are suited to one other” and are not thrown together because of “a random family tie”. The lives of children, servants, and adults should be more differentiated, so that the aesthetic norms on which the family’s socialising was based could be followed in equal measure in an everyday context.

Heiberg also wanted the life spheres of the two genders to be more separate than had been the case for the salon culture, in which Enlightenment ideals of reason had largely determined the vantage point. Women were to set the tone and organise life in the intimate sphere, and men should do the equivalent in the public forum. This distance between the sexes should be demonstrated by men’s respect for women based purely on “the idea of the female sex”. Ladies who venture into the public domain ought by rights to have pins in their clothing, protection against improper contact, writes Heiberg, “a spiked trimming of this kind […] round the waist, by means of which every lady would have a veritable bodyguard”, just like roses have their thorns.

This outline of the mid-century role of woman corresponds to the Romantic ideal of womanhood, an ideal which female authors of the period addressed in their writing. We spot it in the opening pages of Thomasine Gyllembourg’s first novel, Familien Polonius (The Polonius Family), written in 1827. The young hero reports that a copy of Raphael’s Madonna della Sedia hangs in his mother’s boudoir, and that nothing in the worlds of art or nature had ever outshone this picture in his mind: “and from this I can also deduce that a very young mother with her infant child in her arms is for me the most agreeable in Creation, and this period of the female life the loveliest”.

The culture of the intimate sphere as an element in the wider Romantic movement arrived in Denmark from the south; it also, of course, showed up in the other Nordic countries. Barely two years after Thomasine Gyllembourg made her written debut, Sweden saw the publication of the first volume of Fredrika Bremer’s Teckningar utur Hvardagslifvet (1828; Sketches from Everyday Life), which in style and content was akin to Gyllembourg’s stories.

In other respects, the novel as genre fitted the intimate sphere in the same way as the dramatic and lyrical-declamatory genres had suited the salon culture. The reading and writing of novels could be undertaken at home, and although books were certainly expensive to buy, they could be borrowed from girlfriends or from the subscription libraries and book clubs; novels were also serialised in journals – in Kjøbenhavns flyvende Post, for example.

The literary establishment greeted the female authors with mixed feelings. In Danske Forfatterinder i det nittende Hundredaar (1896; Danish Female Writers of the Nineteenth Century), Anton Andersen extols their ethical standards, but he regards their aesthetical results with forbearance: “gute Leute – aber schlechte Musikanten”.

A Woman, and yet a Writer!

The Romantic dualism of the genders equipped women with their own identities, but the role of writer was not one of them. The intense exclusivity of the home, cut off from the civic society beyond its walls, was a necessary condition for the development of sensitivity and womanliness. Women’s active participation in public affairs would be an abandonment of the intimate, domestic life. It would seem a choice had to be made between being a woman and being a writer.

Thomasine Gyllembourg chose to be a woman. She published all her work anonymously, and she was not above expressing a lack of respect for women writers. In a short portrait written for the second edition of Gyllembourg’s collected works in 1866, her daughter-in-law Johanne Luise Heiberg quotes her thus: “It seems to me that we womenfolk have enough to attend to without also concerning ourselves with the like; we must leave that to the men; those women’s scribblings are never of any worth anyway.” The paradox of being the most successful Danish author of her day while having this basic attitude was a circumstance upon which Gyllembourg herself reflected in – as always, anonymous – letters to Kjøbenhavns flyvende Post, written in 1834, and a “Literary Testament” in which she posthumously acknowledged her authorship.

She here intimates that she is not an author in the usual sense of the word. She was not in competition with the great writers who “fly like the eagle to the regions where the naked eye cannot follow”. Her stories are “fruits of life, not of learning and profound studies”; they stem from the “domestic and social life, the specific conditions and complexities”; she contends that as an author, she builds “like the swallow on the houses of people, where it strikes up its unassuming song”. Other women writers of the time directly ascribed a monopoly on artistic creativity to men.

“I remember that towards the end of her [Gyllembourg’s] writing activities I […] had felt somewhat disgruntled with her, because she had not put her name, her identity as the author of the everyday stories – about which I for my part was in no doubt whatsoever – on these [stories] […] had she done so, she would have given us younger ones, who had in some small measure begun to make our way, an authorisation that we too were permitted to produce and publish,” said Benedicte Arnesen-Kall in 1874, when giving a lecture on Gyllembourg in Kvindelig Læseforening (Women’s Reading Society).

This was the case with, among others, Ilia Marie Fibiger (1817-1867), who left a published oeuvre of twelve works: a novel, plays, and tales. She was, as she writes in one of her letters, “a woman proud […] as only few”. Like Heiberg, she was of the opinion that women commanded men’s respect purely by virtue of their female gender, and this wholehearted identification with the Romantic picture of womanhood meant that she turned with anger and loathing against her own urge to write: “There can hardly be any implement to which I have objected more than a pen,” she wrote to her brother. She submitted to literary inspiration as if to an outside force. “I myself do not create, but am afflicted […]. Only where I am sent do I go,” she claims in the preface to “Hagbart og Signe” (Hagbart and Signe), published in Tre Dramer (1857; Three Plays). Elsewhere, she compares herself to a postman carrying around messages from the pen of a stranger. She was unable to integrate the writing self in her female self-image.

Thomasine Gyllembourg’s insistence on anonymity was based on an obvious aversion to mixing together two societal roles, that of woman and that of artist; separation of the two was the thrust of her own agenda. Ilia Fibiger’s aversion to writing, on the other hand, took the form of the (neurotic) anxiety for the pen identified by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, in The Madwoman in the Attic (1979), as anxiety for “male” activity (pen = penis); they perceive this anxiety as being a fundamental factor in the work of women writers in nineteenth-century English literature.

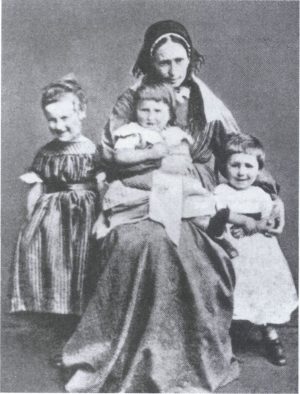

Ilia was the sister of the better-known author Mathilde Lucie Fibiger (1830-1872). The sisters grew up in a home rich in culture but marked by war. Their father, an army man and head of the military academy at which Heiberg was a professor, encountered hurdles along his career path in consequence of his excessively democratic views. Their mother was of an impassioned nature, one which had trouble coping with the family’s constant relocation and financial difficulties. The couple divorced in 1843, and their nine children were split up. Ilia and Mathilde had to seek work as private tutors. They later led an impoverished existence in rented rooms, taking on various jobs – painting porcelain, teaching infant school, needlework. Mathilde finally trained as a telegraphist, and after Ilia’s death she was appointed an official in the telegraph service.

In her young days, Ilia had been in love with a naval officer, Oswald Marstrand; he was killed in 1849, during the three-year Danish-German war. She had hoped to spend her life with him, as wife and mother. She now channelled her maternal energy into helping the sick during the cholera epidemic of 1853; she volunteered as a night nurse at the hospital for the poor – and in so doing, she became Denmark’s first nurse. From 1860 she lived in Copenhagen’s first social housing neighbourhood, the adoptive mother of six abandoned children. At five o’clock in the morning, while the children slept, she would write her historical plays and tales or translate serialised stories for periodicals in order to ensure a supply of housekeeping money.

And yet she did not write from financial need alone; she also had a pressing need to express herself. The verses in the formulaic dramas welled up in her while she sewed shirts or combed her hair. When the body was in motion dealing with the daily routine, words started to take shape. Sooner or later, she had to seize the writing implement in order to commit the ideas to paper. The fate of the manuscripts once they had reached the theatre manager (since 1849 this had been Heiberg), publisher, or bookseller was a matter in which she made every attempt to enlist the help of male friends. Like Gyllembourg, she could not stand “writing women”, and to the author Meir Goldschmidt – one of many targeted to assist with her publications – she wrote: “I am not an author.” To a female friend, she wrote:

“A woman, and yet a writer! To be thus determined by one’s entire nature, by the intense craving of one’s heart – and then merely be content to produce, to write!”

The conflict between Romantic self-image and her writing enterprise eventually caused Ilia to feel “utterly torn apart”.

Hans Christian Andersen in his diary, 10 November 1864:

“Dinner at Eduard Collin’s, I received from Mrs Collin a comedy by Ilia Fibiger, I was to read it and deliver it to Casino.”13 November: “Read Miss Ilia Fibiger’s play To Søstre [Two Sisters, unpublished], it is quite unusable.”

The Sinister Diktat

The conflict between Romantic self-image and “the feeling of being called to a bolder bearing in life, to a more manifest campaign”, to which Mathilde Fibiger admits in the foreword to her epistolary novel Clara Raphael. Tolv Breve (1851; Clara Raphael. Twelve Letters), intensified as the century progressed. The so strongly idealised women had no field of occupation beyond the limited circle of the family. This was particularly true of the many women who never married and who, when their parents’ generation had been put to rest, had neither anything to live on nor for. Some chose, like Ilia Fibiger, charitable pursuits – prison visiting, setting up orphanages, poor relief. During this period, many middle-class women formed institutions to address specific social problems in the name of Christian love.

Mathilde Fibiger was thirteen years younger than Ilia, and she was not content with the role of ‘Good Samaritan’. In her first novel, Clara Raphael. Tolv Breve, she articulated the clear demand that women should have better opportunities to participate in the life of the community. In the politicised climate of the 1840s, the Romantics’ spiritual elevation of woman led to the development of a feminist discourse, Clara Raphael. Tolv Breve being one of its pioneering works.

Mathilde Fibiger was just as bound by the parameters of gender dualism as were the other women writers of the period. Her heroine, Clara, has – like the hero’s mother in Gyllembourg’s first novel – a Madonna hanging on the wall, but Clara endeavours to work out the Romantic ideology of gender role for herself and to recast it in a version that can embrace a more active way of being a woman. Clara’s Madonna is an ‘Ascension version’, which in itself gives an indication of Fibiger’s ideas. The woman should be an intermediary between God and the world; with God’s support, she must disseminate the female values to the rest of the community. Clara writes:

“The woman must take on the man’s mental reality, as otherwise her inner life can easily become one fine figment of fantasy, without creative force and autonomous enterprise. She must preserve her mind as an immaculate mirror, in which she can see the ideal. She must never lose herself in material things, but raise him with her above them.”

Fibiger paraphrases the Second Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians, 3:18: “But we all, who with unveiled face behold the glory of the Lord in a mirror, are changed into the same image.” This citation thus interweaves a theological and a Romantic line of thought, in which the man’s “mental reality” – his point of reference in actuality – faces the woman as the immaculate mirror, an image of God Himself. If, however, the woman insists on her own “creative force and autonomous enterprise”, then she is challenging this “mental reality” of the man. Fibiger’s last and most profound novel, Minona (1854), deals with this confrontation.

The meticulously planned composition of Minona centres on a main storyline concerning brother and sister, Minona and Viggo, and two secondary stories about pastor’s daughter Virginie and single mother Tyra. The key concept is that of ‘love’, a slightly more comprehensive version of the key concept of ‘light’ addressed in Clara Raphael. The struggle is for control of this central energy source. Minona maintains: “There is only one love – the light coming from heaven.” She believes she has her feelings directly from God, and so she considers them inviolable. Viggo, in contrast, represents “duty and the sense of justice” – the laws of society. The two siblings have lived apart since childhood. When they meet again, they fall in love. Viggo tries to resist the illegal feelings they have for one another. Minona, on the other hand, believes in the legitimacy of her feelings, and she confronts her faith with the taboo on incest. She seeks – “in the word of God, the writings of the philosophers, the poets’ accounts of human life” – a rationale for this incest taboo, and she concludes that the world allows itself to be ruled by a “sinister diktat”.

By the end of the novel, Minona has to abandon her faith and yield to Viggo’s “mental reality”. Her conversion happens when her friend Tyra, having given up hope, takes poison and dies with the words: “Life is a lie!” Tyra has pursued a more direct realisation of Minona’s claim to love. She has left her titled family in order to live with her lover, and she has had a child. When the lover abandons her in favour of a well-to-do commoner, she loses faith in this ideal of love. By witnessing her death, Minona thinks she has found the answer she was looking for. “It was not enough for me that it was God’s will – I had to know ‘why’. Now I know – is it necessary to be acquainted with any other feature of poison than that it kills?”

The novel shows, however, that Minona cannot assimilate this supremacy of realities in her personality. Fibiger lets her die from grief. On her deathbed, Minona does indeed defend her new conviction – in lengthy religious deliberations – but she does not convince the reader. We are left with the pale pastor’s daughter as the only viable model for a woman’s life.

In her personal life Mathilde Fibiger also learned to yield to the realities: “The meaning with my life is that I have developed from illusion to reality,” she wrote shortly before her death, with reference to her writing career giving way to a job as a telegraphist.

This tension – between a heroine from the intimate sphere (Virginie) and a rebel against patriarchal law (Minona) – is one of the distinctive features of women’s Romantic writing. It is felt in the novels of Swedish writer Fredrika Bremer and Norwegian Camilla Collett. As the century progresses, the third position – the emancipated woman (Tyra) – appears with increasing frequency.

In Fredrika Bremer’s Famillen H *** (1830; The H*** Family, re-translated as The Colonel’s Family, 1995), Beata Vardagslag, whose surname (meaning ‘workaday’) in itself indicates the intimate sphere, and blind Elisabeth, who is worn to pieces by unrequited love for the head of the family, the Colonel, are the two poles of Romantic love. In her monologues, Elisabeth expresses a proud and defiant womanhood which corresponds to Mathilde Fibiger’s heroines, Clara and Minona.

In Camilla Collett’s Amtmandens Døttre (1854; The District Governor’s Daughters), the heroine Sophie, a young woman with ample opportunities, is confronted with “Norwegian housewives” who by virtue of their “faded characters […] are no longer individuals”. Sophie’s inner wealth is symbolised by a cave in the natural world beyond the social life of the governor’s estate.

In Bremer’s novel, Elisabeth was merely a subsidiary character. In Fibiger’s and Collett’s novels, Minona and Sophie are heroines, though Sophie is of a less radical design than Minona. Sophie’s ‘nature’ is not in conflict with the laws laid down by society. Her goal is the relatively modest one of getting married to the man – the tutor Cold – she loves. Collett claims, however, that this modest goal is in fact unattainable. In the game of love, the “highest winnings” are simply “bait, they are never paid out”.

Mathilde Fibiger was more eager than Collett to learn the true market value of female emotions. In her contribution to a public controversy, Et Besøg (1851; A Visit), she writes:

“Rather than being pure gold, and lie as a display coin, I would like to be exchanged into marketable currency, even if three-quarters of the value is thus lost.”

Collett ‘proves’ the theory that a woman’s love never has a chance of coming to fruition by allowing a misunderstanding to separate them. However, another storyline adheres to Collett’s Romantic orientation, and by so doing contradicts this theory. Instead of Cold, the lover and doubter, the intellectual and visionary, Byron-esque character, Sophie ends up married to a fatherly dean with an affluent, well-ordered home and a little motherless daughter. The young woman’s emotions are “worthy of a king”, writes Collett, but they are exchanged far too readily by her parents in the same way as ‘uncivilised’ peoples “exchange their gold and sandalwood for European metal knick-knacks”. Of the two men, however, the dean has a greater understanding of the best way in which to appreciate and negotiate Sophie’s “gold”. She is certainly unhappy on her wedding day, but the marriage provides her with the opportunity to be “a light and comfort to her nearest, the cherished ideal to her husband, and an affectionate friend to Ada [her stepdaughter]”, and she endeavours to “draw all suffering into the soothing sphere of her tenderness and solicitude”.

Sophie simply ends up in the intimate sphere. She is thus a realistic contrast to Elisabeth and Minona, who want their “gold” to be marketable currency outside the home as well as in it. They salvage their vision of female strength by dying. Sophie crushes her love, tears down “the temple”, but on the other hand she saves her life. At the same time, Collett’s novel salvages contact with reality, as does Bremer’s, in which Elisabeth is but a poignant exception.

Mathilde Fibiger, on the other hand, staked everything on her new woman, on expounding her point of view as an option. But the readers were not convinced; Minona was to be her last novel. With the exception of a few translations, a couple of articles, and a handful of poems, her writing career came to an end just four years after its sensational debut. While writing the closing chapters of Minona, she expressed her feeling of “naturelessness” in a letter to Meir Goldschmidt: “I have the nature of an elf maid […] I am hollow,” she writes. Fibiger wanted to emancipate Romantic womanhood from its tethers to the intimate sphere, but by detaching the psychological components from their social setting, her portrayal of female self-esteem became a shell around a void.

Look More at the Intention than at the Manner of Expression

Female writers of the Romantic movement did not have the academic training in literary tradition enjoyed by the majority of their male colleagues; this did not, however, mean that they approached literature with no prior aptitude whatsoever. If anything, being voracious readers they were stuffed with the male writers’ descriptions of the world and of themselves. They had an overwhelming urge to supplement and correct these pictures of women and the world according to their own minds. Ilia Fibiger’s first literary work was quite simply a rewrite of Carsten Hauch’s drama Marsk Stig (1850; a play about Lord Marshal Stig Andersen). She had attended a performance at the theatre and in 1851 finished her own version, which was more consistent with her understanding of the national-historical material. Camilla Collett launched the essayist section of her writing career by declaring, in Sidste Blade (1868; Last Leaves), that she, like the “captive, recording her statement in her blood on a strip of cloth”, writes from “the prison cell called woman”. Mathilde Fibiger’s manically expressive letter-writer, Clara Raphael, seems possessed by her desire to depict the world as she sees it. The female writers displayed a strong sense of having something new to tell.

They were, naturally, aware that they were inscribing themselves in a literary institution that neither bid them welcome to the profession nor accepted their texts as authoritative. It was not easy to win readers for the images of woman and world that the female writers were attempting to project. “You must remove your critical spectacles and look more at the intention than at the manner of expression,” writes Clara Raphael in one of the letters to her friend, with a despondent sense that no matter how much she might write, she still cannot make herself completely understood: “Were it but possible to explain to you what is so clear to me!”

Women writers had to struggle with the language apparatus they had taken on – the genres, metaphors, narrative voices – bending it to their own purpose. Ilia Fibiger’s work within the fairytale genre is an interesting attempt to make a hero of the woman in a narrative structure that is so thoroughly based on a male brand. The heroine is often launched into an active search for a prince – a gender inversion of the traditional male project – whereupon the course of events is interrupted, for reasons unknown and unforeseen, and taken over by a male hero’s contrary project: to find himself a normal princess. This often results in the two heroes, of each their sex, dying, because her project goes against the societal norms and his project is a suppression of femaleness.

Given that Ilia Fibiger disowned her urge to write and thought that an outside force wrote through her, she was unable to submit her texts to critical editing with the reader in mind. She had made Pilate’s words her own: “What I have written I have written” (John 19:22). The majority of female writers at the time envisaged a readership consisting of middle-class women who shared their experiences and ideals. In Mathilde Fibiger’s epistolary novel, Clara’s letters are addressed to a female friend. In the epilogue to her En Qvinde (1860; A Woman), Louise Elisabeth Biørnsen (1824-1899) writes that the book is written to women since only they will understand “the warnings, the reprimands, and the example that are woven into this simple tale”; the men, she assumes, will be too proud and injudicious in their critique. The women cultivated their texts in an ecosystem that they allowed, both from desire and necessity, to exist somewhat independently of the ‘public’ literary forum. Women’s writing of the Romantic era thus also bore the features of a project in identity formation. This project led to the development of three distinct genres, variants of the main genres in the female canon: what can be called the governess novel, the marriage novel, and the emancipation novel.

In 1850 Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) was translated into Danish, inspiring a number of novels about young women from good families who, due to straitened financial circumstances, have to seek outside work as governesses, teachers, and ladies’ companions in the families of strangers. Clara Raphael. Tolv Breve was the first Danish governess novel, rapidly followed by Louise Biørnsen’s Hvad er Livet? (1855; What is Life?), Cornelia Levetzow’s (1836-1921) En ung Piges Historie (1861; A Young Girl’s Story), Fanny Suenssen’s (1832-1918) Amalie Vardum (1862), and Ilia Fibiger’s Magdalene (1862). In Norway, the governess features in, for example, Marie Colban’s Lærerinden, en Skizze (1869; The Teacher: A Sketch). The genre is that of a female bildungsroman, constructed around the familiar three-phase progress: home – away – home. In the Danish tradition, the first home is the centre of positive values, an original intimate sphere either with the good mother or the foster mother. Social catastrophes in the form of death and poverty drive the heroines from these homes out to other families, where they often experience the subordinate position of governess to be a severe violation of their self-images as women. Now it is no longer the inner qualities, the ‘fair soul’, that count, but only the capacity as a worker. The separation of personality and work duties necessitated by being a wage earner is usually described as an outrage against the young woman’s identity. The aim for the governess is to find her way back to the intimate sphere, either through marriage and thus as wife in her own home, or by returning – as in Levetzow’s book – home to her mother if circumstances there have improved. In contrast to Jane Eyre, the heroines therefore rarely reap positive experiences of life outside the intimate sphere. It is more likely to frighten them; “I ran further and further into the forest, and then suddenly turned and went back,” we learn from Levetzow’s heroine about her exploration of the terrain around the parsonage her foster mother has married into, and where the heroine can now happily spend the rest of her life.

In contrast to Levetzow’s heroine, Johanne Luise Heiberg writes in Et Liv gjenoplevet i Erindringen (1891-92; A Life Relived in Memory):

“Were I in a forest, then I would have to see its outer boundary; only once the glade had appeared intimating the sky outside, could I settle down under a tree.”

The governess novel did not, however, lead its heroine to financial independence – that was only a transitional phase before being returned to one of the traditional stations as daughter or wife. Nonetheless, the thematic core of the genre was in the description of the unmarried young woman’s encounter with the world beyond the home; this addressed a situation forced upon an increasing number of women in the second half of the nineteenth century, and it also contributed to the contemporaneous discussion about education for girls.

With her novel Ægtestand (1835; Marriage), Thomasine Gyllembourg had created the Danish marriage novel, a genre employed by the the next generation of writers such as Louise Biørnsen, En Qvinde, Athalia Schwartz, Cornelia (1862) and Stedmoder og Steddatter (1865; Stepmother and Stepdaughter), and the Danish-Norwegian writer Magdalene Thoresen, Signes Historie (1864; The Story of Signe’) and Solen i Siljedalen (1868; The Sun in Siljedal). In the marriage novel, the heroine wants to achieve a life for herself alongside her duties as housewife. She is a neglected wife struggling to develop her own personality in spite of her husband’s lack of attention and love. In the course of the tale, she is tempted by a lover or incited by her own reckless dreams. In the end, her husband becomes aware of her qualities, or she realises that she has come close to squandering that which is central to life: marriage and motherhood.

The compositional complexities of forming a couple and the internal frictions of a long life together, perhaps in the form of power struggles between the sexes, comprise the thematic core of the genre; as was the case with the governess novel, the proper intimate sphere is the final destination of the tale. The key note of the governess novel is indignation; the key note of the marriage novel is resignation.

The third genre of Romantic women’s literature, the emancipation novel, is represented by works such as Minona, Famillen H ***, Amtmandens Døttre, and, to a large degree, Fredrika Bremer’s final novel, Hertha (1856). These novels also arise out of and profess the ideals of the intimate sphere and its exemplar of woman, but they make a more active and visionary attempt to show the whole of society within this paradigm. This genre was the test site for the breadth of vision of contemporaneous women’s literature.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch