The oral tradition – folktale, legend, ballad, proverb, figure of speech – stemmed from a culture in which written language was something remote and mysterious. Something best left to the clergyman – for he knew a thing or two. Among the peasantry, on the other hand, history, ways of life, and codes of conduct were passed on by word of mouth from generation to generation. The old texts were repeated and re-created, and as long as these stories yielded culturally sustainable models of explanation, the tradition existed as living applied narrative.

From the late 1700s, however, peasant culture gradually disintegrated. This occurred in various ways and at widely different tempi from neighbourhood to neighbourhood and from province to province – in some places the process lasted far into the twentieth century. The oral tradition thus gradually lost its cultural foundation. The reasons were many and complex. The advance of Enlightenment ideas went hand in hand with population explosion and crop failure, the two latter factors making it harder to survive on the mode of production that supported peasant culture. From within the community, Pietist movements had brought about an extensive change in mentality; from the outside, government authorities and the aristocratic architects of rural reform were taking active measures to retrain and transform the sluggish peasantry into agronomic individualists.

The oral tradition thus gradually became homeless, driven out by the mushrooming written culture. It nevertheless survived – at least for a while – and women played an important role in its battle for survival.

The Tongue of the People

When oral culture was superseded by written culture, it was at one fell swoop rendered silent yet visible: having discovered it, the cultural elite stored it – in writing! A national-romantic upsurge across Norway in the mid-1800s triggered a large-scale collection of folklore. In Denmark this “Klappejagt efter gamle Minder” (Hunt for Old Lore), as he referred to it in 1854, was led by Svend Grundtvig. Inspired by his father, educator, theologian, and writer Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig, he considered the peasants’ oral literature to be the “national poetry”, and in 1843 he encouraged all “Danish men and women” to collect old folk ballads: “Furthermore, it was us,” he wrote, “who first began to write by pen what before had only been spoken by the tongue of the people, and Denmark and the entire Nordic region must never forget to thank the worthy women of the manor houses, to whom we owe virtually everything of that which has hitherto been unearthed of our medieval literary tradition […].” (Dansk Folkeblad, 8 December 1843).

In keeping with the Romantic concept that external forms are but a cover, a veil for the actual or essence, Svend Grundtvig did not consider the connection between oral tradition and peasantry to be essential. The “tongue of the people” was just the contingent expression of a common, national heritage; the dirty, work-gnarled people, in whose care “the national treasure” was stored, were, along with the oral aspect, a stratum that could be removed, allowing the actual thing – the poetry – to emerge.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the Romantic current merged with the positivist endeavours of the Modern Breakthrough in Denmark. From a position of idealisation, the oral tradition was now made the object of scholarly objectification. This did not mean that oral literature was thereafter seen within the parameters of its cultural circumstance – that comes in the cultural history of a later period – but it meant that information about an informant’s gender, age, and social situation was now just as carefully recorded as the narrative.

The pioneer of the modern version of folklore research was Evald Tang Kristensen (1843-1929). While Svend Grundtvig came from a completely different social stratum to the individuals whose narratives he was collecting, and never really had any personal dealings with ‘the people’, Tang Kristensen came from and worked among the rural peasantry. As village schoolteacher he was embedded in the culture of the countryside, and as folklore collector he roamed the length and breadth of Jutland. If he heard about someone who could sing or narrate, he would spare no effort in going to see them. Neither time nor money – nor the lice he often took home from a night’s lodging – could keep him away.

The contrast between a Svend Grundtvig and an Evald Tang Kristensen bears witness to an epochal shift in the prevailing culture. Where Svend Grundtvig is the distinguished solitary man of letters who distils the information accrued, Evald Tang Kristensen is both scholar and collector. The existence of an Evald Tang Kristensen shows that the bourgeois mono-culture was disintegrating, and gives notice of the change that would make it possible, a decade into the twentieth century, for the women collectors to step forward, too.

The Hidden Pattern

From the 1850s and up until his death in 1883, Svend Grundtvig had contact with approximately 300 collectors from across Denmark. Many of these collectors were clergymen or teachers – at the colleges, the young country lads who aspired to a teaching career were encouraged to record in writing what they knew of folklore. The folk high schools’ national-romantic revival of rural youth also led to an increase in the work of recording the oral tradition.

Unlike collectors in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, who – as Svend Grundtvig wrote – chiefly comprised “worthy women of the manor houses”, Svend Grundtvig’s collectors were mostly men. Despite the quantitative preponderance of men, some women did occupy key positions – albeit in low-profile roles that were hard to spot.

From the very outset of Grundtvig’s activities, women were centrally placed in the underlying pattern reflected in the collection work. Thus – it was said – one of the first contributions came from his godfather, the poet B. S. Ingemann, at Sorø Academy: a small collection of legends from the parishes of Pedersborg and Slaglille near Sorø. This is correct, the only snag being that the legends were recorded in 1826 by his wife, Lucie Ingemann, and that the legends had been narrated to her by “Trolde-Margrethe” (lit.: Margrethe the troll-woman) at “Parnas” (Parnassus) on the other side of Sorø Lake and by “Karen Goldamme” from Slaglille. This is a typical pattern. Even when women came up with the raw material – as narrators, as recorders – folklore still ended up being men’s business.

Contrary to this pattern – which followed the sharp divisions laid down by bourgeois society between male and female, public and private – a number of women were taking a new and different approach.

One of the more striking was Frantziska Carlsen (1817-1876). She divided her time between the estates of Rønnebæksholm and Gammelkøgegård, owned by her father, and Copenhagen and Vallø Stift, (a stift being a foundation for unmarried daughters of the aristocracy). Her greatest efforts on behalf of folklore collection took place between 1854 and 1857; not only did she personally record the legends and folktales of southern Zealand, she also drew on the work of a close network of female friends and helpers.

One of these friends was Baroness Elisabeth Krag Juel-Vind-Arenfeldt (1806-1884) at Stensballegård Manor, near Horsens in Jutland. She undertook her collection at the same time as Frantziska Carlsen was making her recordings and, like her friend, she covered most folklore genres. She, too, went out in the field herself, as well as drawing on the work of helpers.

She received a considerable amount of help from the young Nanna Reedtz (1835-1862), who stayed at Steensballegård for several extended periods. Nanna Reedtz also formed her own corps of collectors. In her childhood home of Bisgaard in the parish of Tamdrup, she got the estate manager to record folklore from his home district, Himmerland; the private tutor from his childhood village, Torrild, and a friend from north Zealand, Miss H. Poulsen at Egelund Manor, were set to work recording in the Fredensborg area.

These women saw their work as a vocation. By helping to unearth “the national treasure” they made their contribution to the spiritual and intellectual development of ‘the people’. In no way did they see their activities as a breach of the woman’s role of their day. Seen in a longer historical perspective, however, they were pioneers breaking with the invisibility that had hitherto cloaked the bourgeois woman’s ‘care work’ – be it as collector, or wife, or in other ‘supporting roles’. In this way, the collecting women were moving closer to the position of a Grundtvig. They did not just give of their knowledge, they constituted the central collection point within their respective networks. They actually arrogated to themselves an authority at ‘middle manager’ level, which put them in a very different category to a Lucie Ingemann.

This ability to navigate the hierarchy was a result of their particular social or marital status. They were exceptions to the rule in that they had a more or less free hand. They were either unmarried or married in a manner that did not box them into the respectable female citizen’s position as guardian angel. They acted both as feudal relics and as forerunners of the single, independent woman who became a feature of the late-nineteenth-century societal landscape.

Frantziska Carlsen, in particular, can be seen as a harbinger of the coming development. She did not merely ‘settle’ for being a collector and recorder. She used her pen to write her own words – books about her home district and her childhood. Her singular contribution gave a foretaste of what would become daily fare after the turn of the century.

The Female Folklorist

Progressive social development, as reflected in the rural culture, not only created the conditions for a village boy such as Evald Tang Kristensen to pursue an enterprise in which vocation and public visibility went hand in hand – the village girls were also on the move. Women who had grown up in a traditional village culture found themselves, as adults, in a situation where they had effectively been set free. They were no longer ‘peasant’ women, but as women – and women from what was known as ‘the working people’, at that – they had no direct access to education and jobs. They mastered written language – in this the folk high school movement, among other factors, had borne fruit – but they were nevertheless excluded from the bourgeois society’s written culture. For a good many of these women, collecting folklore was a route to a visible social identity.

During the first decade of the twentieth century, a number of women gained a name and a certain – albeit modest – reputation as authors of regional portraits; some of the most well-known being Christine Reimer (1858-1943) from north Funen, Karoline Graves (1858-1932) from western Zealand, and Helene Strange (1874-1943) from the northern part of the island of Falster.

In the varied assortment of regional portraitists, Helene Strange can be seen as a compound of the features scattered among the other female writers. Like women of the previous generation, she started out as a collector and errand-girl for Hans Ellekilde, the then-leader of Dansk Folkemindesamling (Danish Folklore Archives). However, as local history societies eventually popped up around the country, she found an outlet in the yearbook of the Lolland-Falster historical society, by means of which she could circumvent the established authorities and publish the narratives she had recorded. The next step – the one that would lead to telling her own tales and giving her imagination free rein – was then not so great. She was countryside born and bred – she had drunk in the rustic tales with her mother’s milk – and she could write too, so she soon broke away from the ‘middleman’ and launched herself as a writer on cultural-historical subjects. Storyteller, mediator, and author in one!

The coming together of oral and written culture in the individual woman created this – modern – type of writer and the specific genre that portrayed the life and customs of ordinary people. Cultural history in a scholarly sense, with an overarching perspective that can objectify and combine the individual details into a particular systematism, it is not. Nor is it folklore. It is a hotchpotch of the one and the other and neither.

The portrayal of the life and customs of ordinary people is an expression of a rationalist view in the sense that everything – what is told and what is lived – is noticed and noted and questioned on the basis of an unambiguous truth criterion: can this or that be verified as fact, or is it superstition? At the same time, however, it is the irrational – superstition – that interests the narrator, and it is therefore that which fills most of the pages. In another way, too, the oral tradition seeped into the writing. As the folktale was a practical utility narrative – a continuous ‘discourse’ of the circumstances prevailing in rural society – so the portrayal of life and customs is bound by the situation. With no overarching systematism it ‘talks’ on and uses the rhythm of everyday life, changing work processes, the progress of the seasons, or life’s watersheds – birth, marriage, death – as occasions for a form of associative narrative. What particularly links these portraits to folklore is, however, the fact that universal and personal, objective and subjective explanations are woven together and entangled with the portrait to such an extent that it is impossible to spot where one stops and the other begins. Despite the attempt to objectify, the writer has thus yet to become individualised in relation to the material.

Nor can the writing be called modern. The traditional material is not capitalised on as a style, a timbre, that re-creates the mental characteristics of peasant culture in writing. On the other hand, Helene Strange, for example, uses the tradition as a narrative layer serving to add local and period colour to the description. Even when she is ostensibly writing fiction, it seems more like ‘object lesson’ than art.

“I have had the pleasure of seeing that many have followed it with interest, but this has not put me under any illusion that I have perpetrated a masterpiece; far from it, but I have to the best of my ability endeavoured to provide a ‘dressed up’ cultural-historical exposition.

During my work in the field of history I have noticed that people are loath to engage with the actuality of cultural history, and accordingly I have ‘fleshed out’ this little piece of north-Falsterian cultural history.”

Helene Strange’s characterisation of her regional novel set on the island of Falster, Priergaardsslægten I-II (1922-23; The Priory Family), in a letter dated 10 May 1923.

A genre full of contradiction, it joined forces with an equally paradoxical specimen: the regional movement. This movement was a steadfast attendant to the modernisation of rural communities: a nostalgic attempt to maintain the regional culture now in the throes of being dismantled. At the same time, however, it was a highly modern phenomenon that advanced the process of democratisation in the local regions and the switch over to a more rational mindset. That which, in the established bourgeois community, was an impediment to the female folklore collector – class and gender – was an absolute advantage in the context of the regional movement. The former country girl had, so to speak, an innate right to the matter in hand.

Where the female collectors of the 1850s had an expedient relationship to the folklore, the case was somewhat different for the woman of the 1900s. She had now been given a completely different rein – she had to earn her own living – and this new departure had led her into a dilemma of identity: neither ‘real’ woman nor ‘real’ man, neither peasant nor burgher. In this situation, folklore acted as a bridge between oral heritage and the written culture to which the woman aspired. Here, she could both display aspects of herself – show herself as she was – and train an empowering, objectifying relationship to the self. The regional movement and the craze for portrayal of life and customs was the culmination of a one-hundred-year endeavour to fix the oral tradition as a cut–and–dried form. Finally, written culture imperialised the last remnants of the oral culture and also turned the countrywoman into a writing individual. In writing her heritage, she signed it away – but by so doing she inscribed herself into the modern society as an individual with a name and identity.

“Research into regional issues, following scholarly methods, addresses not only the past, but also the present and future, asks not only ‘whence’, but also ‘where to’. It seeks causal connection, and is constantly asking ‘why’; […] It sees the local as the basis of the national and international, and wants to teach the population to see and feel the coherence in the life of place and lineage and to make the individual feel like a living and acting part thereof.”

Regnar Knudsen’s characterisation of the regional movement in 1926, citation from Lolland–Falsters Historiske Samfunds Aarbog 15 (the Lolland-Falster Historical Society Yearbook 15).

Writing Down the Far “Too Natural”

Collecting and writing down was not a completely straightforward matter. Men in particular had – they thought – problems with the women collectors. In 1885, for example, Miss Charlotte Plum from Broager asked Evald Tang Kristensen for help in changing the style of her notes, as she was not capable of writing a language that was suitably “plain and folksy”. Moreover, she found people “too natural” and she often had to ask them to rephrase their narratives. Hans Ellekilde simply thought that most women were unsuited to the work of recording folktales: “They confined themselves exclusively to the ballads, like their predecessors.”

Several points can be drawn from these statements. Firstly, they bear witness to a clash of cultures. A woman like Charlotte Plum, who had a bourgeois upbringing, was simply equipped neither with the written language nor with the forms of comprehension necessary to ‘grasp’ the oral tradition. Its devices span from the subtly hinted to the grotesquely exaggerated. The metaphysical dimensions are often represented by roughly-hewn animal and human figurations in which bodily orifices or gender characteristics are overmagnified. Where the burgherly art idealised and harmonised, the folklore tradition was coarse and contrastive.

Secondly, Charlotte Plum’s travails show that the Romantic attitude to folklore was still alive and kicking in the late 1800s. In contrast to Evald Tang Kristensen, who endeavoured to record all the sounds and gestures in the written language, this “natural” aspect was clearly peripheral for a woman like Charlotte Plum. She asks people to rephrase their narratives because she wants to track down the ideal core behind the verbal presentation.

Imbalance of this kind, between recorder and informant, shows how difficult it is to get a handle on something ‘original’. The oral tradition recorded in writing has been through a good many filters, and even the actual narration to the collector was an enterprise imposed from the outside. Above all, the act of oral communication is by definition bound to the physical body, but in being transferred to written language it is passed on outside the body. Moreover, the narrative situation from which the written material stems has generally been an artificial setup. The collector will have sought someone out and then asked her, on the spot, to deliver what she could. This would have guaranteed neither the performance of her usual repertoire, nor that she had narrated everything she knew.

Evald Tang Kristensen found his best informants among the oldest members and the worst-off section of the rural population. In all likelihood, this reflects a situation in which the younger and more affluent people no longer needed to remember the tales they had been told in their childhood. Most of the material was recorded in the latter years of the nineteenth century, a time at which modern cooperative farming displaced the last remnants of the old rural culture. The traditional working partnerships crumbled away, and with them the storytelling situations in which the oral tradition was rooted. Only the old people had lived with the narratives, and only the poor people still living in a pre-industrial sphere had need of them. That these very groups were the ones so keen to be informants is probably also due to a more concrete factor – they were paid to do so! Payment for the narratives was the largest item of expenditure on Evald Tang Kristensen’s budget for his collecting trips.

Similarly, information about the men’s and the women’s favourite genres only makes certain tendencies probable. Evald Tang Kristensen’s meticulous records suggest that men chiefly told folktales, while women mainly sang ballads. “The men have,” he wrote in 1884, “by and large, been my best source as regards folktales and women as regards ballads. These latter are seldom very good narrators and are not that comfortable in seeing their narratives written down […].” And in 1926 he supplemented this observation with:

“It seems as if the women had a feeling that it was not becoming for them to pass on something to a visiting man they did not know.”

Kerlingabækur – old wives’ tales, superstitions – has for centuries been a common term in Iceland for the mystical and ‘superstitious’ recordings from folk culture. In his foreword to Iceland’s most extensive collection of folklore, Jón Árnason’s Íslenzkar þjóðsögur og ævintýri (1862-64; Icelandic Folk Legends and Tales), Guðbrandur Vigfússon wrote: “Mothers and women have always been some of the best narrators, and without them our sagas and legends would have been long since lost.”

This last conjecture probably goes some way towards explaining the absence of women from the genre. Other collected narratives show quite clearly that women were perfectly able to tell folktales – even very coarse ones, at that – but by all accounts women mostly told their tales when they were in exclusively female company. The clear-cut boundaries in the rural community between men’s and women’s work made for a culture that was just as closed to men as the public sphere was to women. And, of course, “a visiting man” could not simply enter that compartment without further ado.

Like Evald Tang Kristensen, the Icelandic collector Sigfús Sigfússon was also interested in the lives of the informants. Between 1922 and 1958, he published a major collection of Icelandic folktales in which the informants’ names indicate that the Icelandic women – unlike women in Denmark, for example – were the dominant agency within the folktale genre. Sigfússon’s informants, like those in the other Nordic regions, also had an extensive repertoire of folk legends about bewitched men and women.

Gender and Genre

With the aforementioned provisos, the folktale must nonetheless be said to be a genre that men have found easier to handle than have women.

The folktale was – and was perceived as – ‘fiction’. Something that was not real. A fantastic tale requiring a degree of professionalisation and individualisation, which the itinerant storytelling man was usually able to acquire. Not everyone was allotted the talent to be a good storyteller. A repertoire had to be built up and stylistic ingenuity cultivated in order to hold the attention of the listeners – the narrator was not presenting them with anything ‘useful’ – and, in addition, the genre’s compositional and sequential requirements had to be observed.

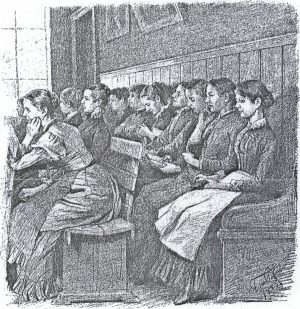

On the other hand, the ballad was a genre that followed fixed stylistic and metrical rules. There was less requirement for individual creativity vis-à-vis the actual material, and whereas the folktale needed listeners, the ballad with its endless series of stanzas fitted in nicely with the often solitary and mundane woman’s work. The housewife on the little homestead spun yarn on her own, and she attended to stable and kitchen on her own; in order to avoid the poorhouse, many old women scraped a living by weaving and darning for the farmhands in the village. These women trod the musical boards of the ballad rather than those of the social sphere, from which they had been excluded by virtue of their hardship.

Like the ballad, the folk legend was a genre depicting everyday life – and, as such, legend was not just the men’s but also the women’s mode of expression. Folk legend was closely bound up with daily life but, in contrast to the ballad, the telling of the tale required time spent in a common forum. In the evenings, when the whole household was gathered and everyone – depending on gender and age – was busily engaged in various types of domestic industry such as rope-making, woodwork, spinning, and hand-carding wool, then the stories were told. Someone started, someone else made additions or improvements, whereupon a third person picked up the threads that had been laid out and took the tale onwards. Folk legend was a collective genre; telling-by-turns served as constant repetition and revision of the rules of conduct and the understandings that structured the village community. For a culture in which written language was unknown to most, the folk legend constituted an ongoing collective working in and working up of history, law, religion, and morality.

The legend is, therefore, close to ordinary everyday conversation. It bristles with implicit meanings and fixed expressions, and the narrator’s personal outlook is only perceptible in the tone of the language.

The folk legend was also a fixed ingredient of everyday life in another way. In contrast to the folktale, it deals with reality and its constantly new vicissitudes, and while the folktale is universal – it stretches from east of the sun to west of the moon – folk legend is local. Folk legend describes named persons and places, and is generally based on a conflict in which humankind is brought face to face with nature and its unknown forces. Pre-industrial rural society did not view nature as recreational and idyllic. The wolf could only just be kept from the door even under the most favourable of conditions, and the least misfortune, the smallest slip-up, could put life and livelihood at risk. Nature commanded forces that should not be challenged. In the folk legends, these dangerous and mysterious powers are rendered recognisable and manageable in the guise of wood nymphs, elves, goblins, werewolves, and other human-like creatures.

In its narrative form, legend functions as an incantation, a warning, an affirmation, a thought. The oral tradition does not think in factual circumstance and abstraction, but in metaphor and momentum. And regardless of the material – be it a legend of mountain folk, auguries, or apparitions – the folk legend tradition bears witness to the vulnerability of the social structure and to humankind’s fragile dependence on nature, and shows how easy it was to err – to be bewitched.

“One day, near Markbæk between Tiset and Kastrup, a woman was out walking in the middle of the day, and it was as if sleep overcame her, and so she lay down by the roadside. Just south of the road and east of Markbæk farm there was a hillock not many steps from where she lay. But as she awoke, a little green man jumped off her, and it was said that he had put the sleep upon her. It was also said that after this she bore a child. This I was told by an old woman, when I was a small child.” (Ane Marie Møller, Bovlund).

Legend cited from Evald Tang Kristensen: Danske Sagn som de har lydt i Folkemunde, Ny Række I, 1928, nr. 650 (Danish Legends, as narrated by the local people, New Series I, no. 650).

Bewitched

“While my mother was in the service of Jens Hansen at Tågeby, there was a girl called Maren in service at the parish bailiff’s. At that time all the cattle wandered freely on the common land in the autumn, and when it was cold then they wanted to go into the forest, and there is a lot of that in the area. So, one evening the girl went out to do the milking, and when she got there the cattle were over in a bog, known as Rævemosen [Fox Bog], in Tågeby Kohave [enclosed meadowland]. It was known to be a place of elves, and no one liked passing by of an evening. Just outside the forest there is a hill, Træhöj [Wood Hill], which, incidentally, is still used as a landmark. When she had finished the milking and was on her way home, the girl had to walk past Træhöj and an elegant maiden came out of the hill, and a little dog that the girl had taken with her raced straight up to the maiden. The girl walked over to her, she looked to be very nice, and called to the dog. The maiden invited her to come along to Rævemosen, for there was to be a dance that night. The girl would most dreadfully like to go along straight away, but first she had to take the milk home, and so she ran as fast as she could, all the while spilling it freely. She ran into the scullery and put down the bucket so the milk splashed out and all over. She wanted to leave again straight away, but the farmer’s wife, who was standing there, was angered and scolded her for spilling the milk like that. Well, she had to make haste, she said, for she was going to a dance. ‘No, you are not, you are staying here and helping me strain the milk.’ There was no one else at home except a tenant smallholder, who stood thrashing straw, and when the girl now started running, the farmer’s wife bounded after her and grabbed hold of her skirt. The girl hit out at the farmer’s wife, who then called to the smallholder and he came and helped her get the girl to bed, and then they used water and lead [a magic cure]. It did not help immediately, however, but she eventually became so good that she got married. She never really got over it though.” (H. P. Nielsen, Sejling).

The ‘bewitched’ motif – here in a Danish variant of the ‘bjergtaget’ genre, literally ‘taken to the mountain’ – is found throughout the Nordic region. In Iceland the dangerous forces dwell in the mountain pasture, in Norway most often by waterfalls and mountains, in Denmark by bogs and barrows, and in Sweden by the forests and charcoal stacks. The folk legend cited here has features that are characteristic of the genre: the narrative is based on a single episode, and proceeds from an introduction to a dramatic kernel followed by a conclusion. The introduction might be very brief, stating the bare necessities of time, place, and persons involved, or, as here, it might be more comprehensive. This depends entirely on the situation – whether or not the listeners are already familiar with the localities described – and on the temperament of the narrator. The dramatic core of the tale sees the everyday, familiar world confronted with a world that is both similar and dissimilar. The elf maid appears in human form, but unlike Maren, who literally has her hands full of work, she is “elegant”. She entices the girl with something that contrasts sharply with the mundane toil – she invites her to a dance. Joy undreamt of! And hits the spot bang on: the girl wants to, yes, would even “most dreadfully like to go along straight away”.

The danger of desire is also apparent from a widespread Icelandic legend found in a number of versions in Jón Árnason’s collection Íslenzkar þjóðsögur og ævintýri (Icelandic Folk Legends and Tales). A man is rescued from a shipwreck by a maiden of the huldufólk; she gives him shelter, food – and love. When he finally gets back to the human world, he refuses to acknowledge paternity of the child she is expecting. Thus far, the legend tracks the ever-lurking danger in an ordinary – unmarried – peasant girl’s life. Unlike the peasant girl, however, the hulder girl has the power to punish the faithless man, so that not only she, but also he, is excluded from the community. He is therefore often transformed into a monster, spreading death and misfortune wherever he goes.

The extremely human urge to let go of the reins and give way to desire here and now is given a forceful erotic perspective in other folk legends of the same type. In these, the elf maid might entice with dance and song, she is perhaps delicate and slender of appearance, with loose, flowing locks, and flimsy robes, or she might be endowed with an impressive bosom and make explicit invitations. Whatever the case, she is dangerous precisely because the person she meets is made to let go of everyday life. In this story, her invitation alone is enough to stop the girl being able to control herself – she has been possessed! In other folk legends this possession means that human time disappears: one minute spent in the hill and one hundred years have passed in the human world. As an expression of the flipside of desire, the elf maid who is so seductive upfront is usually also equipped with a hollow back!

At the culmination of the drama, two worlds battle for control in the unfortunate human being. Sometimes – as is the case in this story – helpers step in. On other occasions, the affected person has to be self-reliant and take to their heels, run away, or employ cunning. The mountain folk are indeed not all-powerful, they can sometimes be overcome. Not by means of reason, but through counter-cunning and magic: the sign of the cross, jagged iron or – as in this story – lead and water.

The conclusion, which is generally quite concise, specifies both the short-term and the long-term consequences. The story quoted here ends relatively well – the agents of duty get the better of desire, and the girl “became so good that she got married”. The legend does not waste words on what this might involve: marriage was so inevitable, so indisputable in peasant culture that it was not a matter for debate. It underwrote the ownership of property, survival, and cultural identity. In contrast to the bourgeois marriage, marriage in the peasant community was not a forum in which to develop individual inclination; on the contrary, it was a public forum connecting the individual to the community. If you were unmarried, you were left high and dry. Particularly if you were a woman.

In Iceland the contrast between hulders and peasants was less clear-cut than in Denmark. Hulders in the Icelandic folk legends, therefore, often take the guise of ordinary people. They are farmers or fishermen – and their backs are not hollow. But they are seductive and fair of appearance! In some of the tales they are said to be descended from Lilith – Adam’s first wife, who was not prepared to submit to the man’s wishes. God sought in vain to make her listen to reason, but finally had to give up and create a new man who was better suited to her. These variants show that the Icelandic folk legends, in contrast to those from the rest of the Nordic region, were the product of a society in which the individual, and thus individual desire, was given wider – and perhaps more precarious – scope than in most peasant cultures.

Demonic Gender

Displacement tells its own tale of the conditions that render the individual vulnerable to demons. Any transition – on the road or on a journey from one state of affairs to another – is a particularly sensitive situation. As in the folk legend cited, for example: the pre-marital state in which the young woman is no longer a child, nor is she yet a married woman. Or – as also addressed in this tale – when an individual is beyond the control of the community: she has gone outside the cultivated areas. In a rural community, where loose-housing systems for cattle were common, milking time was one of the ideal opportunities for demons. In other folk legends – especially Swedish ones – the demons’ hunting ground is located around the charcoal stacks, to which the men came from afar to work.

On this trip – to the cows, for example – women are again far more vulnerable than men. In the majority of charcoal-stack tales, the men sort out the situation by thrusting a burning stick up under the mountain woman’s skirts, whereas by no means all the girls manage, like Maren in this legend, to save themselves. This thematic difference reflects a historical disparity between the conditions of life for men and women. Men had a much greater radius of movement than women did; the men’s work territories stretched far and wide – even as far as the market town when goods were to be sold – while the women’s lives were enclosed within the confines of the farm. In the rural community, therefore, meeting a solitary woman on the road gave cause for misgivings: “A good housewife in the rural village was meant to stay indoors on the farm or in the company of her husband. The higher her prestige, the more suspect it was if she was seen out alone. Various accounts relate that the worst possible scenario was to meet a really respectable lady,” writes Jonas Frykman in Horan i bondesamhället (1977; The Whore in Rural Society).

However, the milking had to be done – and as this was usually work undertaken by the young woman, she was constantly in the danger zone. The married woman, on the other hand, had no reason to feel all that safe either. In particular, the vital dealings with milk were instrumental in rendering women vulnerable: a culture with no rational understanding of chemical transformation processes viewed the working-up of milk into butter and cheese as a magical enterprise in which it was absolutely essential to observe quite specific ritual precautions. The explanation as to why it nonetheless frequently proved impossible to make the butter coalesce was consequently also of the magical kind. Over the years, countless are the old, odd, or in some other way ‘eccentric’ women who have been elected the culprit – having taken up residence in the churn or milked someone’s cows by means of a darning needle in the wall.

Women were especially vulnerable to demonic forces during pregnancy. For one thing, it was always questionable whether or not a woman would survive the delivery; for another, forces beyond human control had, after all, physically possessed the pregnant woman. It was as if she was allied to the subterranean powers. In all pre-industrial rural societies, therefore, a profusion of rituals and rules stipulated how she should behave in order to prevent trolls, pixies, dwarfs, and the like from taking over. In fact, the pregnant woman was sometimes so very vulnerable that not even her own husband could stay put in his skin; assuming the form of a werewolf, he would attack his wife. When in this guise, he found her apron particularly covetable – the apron, however, was also the woman’s weapon against the werewolf. Thus a recurring feature of these folk legends is that the man is revealed as a werewolf when he returns to his human form and still has threads of apron fabric stuck between his teeth. The dual function of the apron in the legends – manifesting female weakness and also female strength – endows it with a significance beyond that of the purely utilitarian. The apron symbolises female virtue, which in the rural culture is the same as diligent competence. One of the most conspicuous differences between descriptions of country girls and descriptions of elf maidens is, therefore, this apron. The elf maiden does not work, she does not wear an apron; on the contrary, her enticement is projected by means of a blurred bodily configuration without hard-and-fast garments and contours. Gender is not fixed behind a specific item of clothing, but is spread across her entire appearance. The apron thus symbolises both virtue and the demonic element of the female body – and therefore becomes the werewolf’s point of attack.

“[…] Let it be said, the man was a werewolf, that was plain to see for his eyebrows met above his nose. It once happened, while his wife was with child, that she went with him to Nykjøbing, and, when they got to Lindeskoven [the linden tree forest], the man had to go in there for a moment. No sooner had he tethered the horses and gone into the forest than a foul hairy animal tried to climb up into the cart to the woman. She immediately undid her fine new linsey-woolsey apron and pummelled the creature, and indeed eventually it had to leave empty-handed, but not until she had almost worn out her sturdy apron on it. Then, shortly afterwards, the man came back, indeed, and true to tell there were some threads from the apron stuck between his teeth.”

(Karen Toxværd, Sillestrup).

Folk legend excerpt cited from Evald Tang Kristensen: Danske Sagn som de har lydt i Folkemunde, nr. 16 (Danish Legends, as narrated by the local people, No. 16).

The bewitched motif expresses an existential conflict between desire and duty. It occurs in all genres of folklore, but features frequently in the folk legend tradition. This is not because peasant culture was puritanical or pleasure-denying; on the contrary, everyday life was lived within a framework of celebrations marking the transitions of year and life – such as baptism and harvest – when pleasure and desire were paramount. There was feasting and drinking, dancing and flirting – openly and shamelessly. The legends show that desire is not a danger until it defies control by the community; a community, such as the pre-industrial village, existing on the bare minimum, could not ‘afford’ individual manifestations of desire. Acted upon beyond the remit of communally organised and ritualised procedures, desire would prove fatal. The folk legend cited above, which in this respect is prototypical, also offers an explanation for this view: the erotic impulses are not an integrated part of the human psychological make-up, but something beyond the individual’s control, something that strikes from the outside. Unlike the individual of cultured bourgeois upbringing, the person brought up within the peasant culture had not internalised his or her agencies of compulsion. They were not manifest as psychological inhibitions, but as tangible external threats and reprisals – from the squire, the bailiff, the community. People in general, and women in particular, were therefore vulnerable when alone; then you had to tread carefully – close your eyes and ears – otherwise you would be possessed.

‘The bewitched dairymaid’ is a recurrent motif in the Icelandic folk legends. The basic fable is thus: “At the onset of summer, the girl went to the mountain pasture to take care of her father’s sheep. There she sat, in all her solitude, when an exceedingly fine-looking young man appeared before her. His words were sweet, and the girl melted – yielded.

“At the onset of winter, she returned to the village and she had become suspiciously stout in the midriff area. Despite the villagers’ gossip and her father’s supervision, however, she managed to escape when her time came. The hulder man was awaiting her in the mountain pasture and he protected her as she gave birth. The baby stayed with the hulder man, while she had to return to her father, who soon forced her to marry a dependable farmer. Yet, she managed to exact a promise from her husband that he would never receive strangers without asking her first.

“Time passed – she was never happy, but always dutiful. And then one day two men arrived at the farm and asked the farmer if they could have shelter for the winter. As he had made his promise so long ago, and he did not want to seem like a henpecked husband, the farmer invited them in. His wife, who had heard everything, turned pale and hid. She tried to avoid the strangers at all times, but in vain. One day she looked into the hulder man’s eyes and, at his side, she recognised her son – for it was they! The hulder man and the woman embraced one another, and at that very instant they died from grief.”

There are a number of variations on this tale in Jón Árnason’s Íslenzkar þjóðsögur og ævintýri (1862-64; Icelandic Folk Legends and Tales).

The folk legends’ quality of everyday, colloquial language is the most obvious reason for the female storyteller still being a well-known character around the turn of the century. Among the worst-off section of the rural population – those who as yet only lent body and toil to the abundant blessings of the new world of cooperative farming – illiteracy and peasant mentality survived into the 1900s. Once democratistion in the form of better schooling had become widespread, however, folk legend as a natural element of cultural communication disappeared. And yet the question remains: has it ever died out completely? Might it not still thrive as a writing-less vein running alongside everything else we tell one another? Alongside all that can be rationalised, all that has an express purpose.

The Story

Nor did the folktale vanish without further ado. It had long since gained a footing in the written culture, where the typical three-part structure – at home/out into the world/back home – can be traced way back in the history of European literature. With the rise of the bourgeois middle classes, starting at the end of the eighteenth century, the folktale was assimilated with the novel in the so-called bildungsroman. In this genre, the three-phase sequence corresponds directly to that of the folktale, whereas the magic helpers and the journey to the land of the dead, which are characteristics of the earliest versions of the folktale, have disappeared. In a bildungsroman, the land of the dead has been replaced by a psychological field of conflict that the young person must learn to control before being able to return home – to become one’s self in an individualised sense.

In the late 1800s, the bildungsroman changed its profile and became a novel of decadence – a genre shift showing that the inherent tension between individual and outside world has been intensified. The hero no longer reaches home – there is no home – and the narrative tract has been broken up into episodes.

The dialogues, which in the bildungsroman usually consisted of long well-formed reasoning, have become snatches of speech that are not intended to carry an argument or a deduction, but are there to characterise the individual in the specificity of the situation. Orality – the idiomatic remark, the syntax influenced by spoken language – has now invaded written language, but it is an orality of the moment, transient. A denial of every tradition.

Transition to the twentieth century, however, gave the oral tradition a new lease of life within the written culture. A literary re-orientation occurred, at slightly different speeds, in all the Nordic countries. This was partly a result of social mobility, by means of which hitherto oppressed groups pressed forward and arrogated ‘a seat’ for themselves at the public literary table; partly a generational rebellion turned against the ‘tired’ and ‘decadent’ symbolism of the 1890s. This neo-realism, or popular realism, as it was also called, obviously gave space to voices other than that of the dominant bourgeois culture. Untrained voices – female voices!

Many of the young writers were women who had grown up with the oral tradition running in their veins. For not becoming fishwives, farmers’ wives, clergymen’s wives, or other female appendages to husband and station, they could thank the break with peasant culture and pre-industrial ways of life. But that they became writers – some of them major writers – was thanks to the influence of folk poetry on their language, their musicality. Women such as Selma Lagerlöf in Sweden, Marie Bregendahl in Denmark, and Sigrid Undset in Norway brought together the individualised speech of the Modern Breakthrough and the collective speech of the peasant culture.

Thus, in their writing, the narrative mode is joined with the episodic, the individualisation of dialogue with the collective register. In their works the story experiences a renaissance – not as a closed sequence of development, but as a mosaic of tales weaving in and out of one another in a simultaneously processive and iterative movement. Their realism is, in its way, suitably ‘realistic’; but the almost contrapuntal aspect of their compositions adds dimensionality to the realistic universe, inserting a magic depth. In folk realism, the closed domestic space of the bourgeois novel of decadence has been opened. Several dimensions of space and time are often set in counterpoint, so that the nature forum – again – becomes unknown and alluring.

An intricate and sometimes invisible line runs from the peasant ‘literary’ tradition to the major folk realists and on to what is today known as magic or magical realism; a genre that, unsurprisingly, has a Latin American axis – in countries where the confrontation between modernity and traditionalism takes place far more forcefully than it did in the Nordic region around 1900. The fantastical elements are, however, also perceptible in modern Scandinavian literature. The freely imaginative, breaking through the unities of time and place while operating on several levels of consciousness and temporal axes, is a literary phenomenon which, in a way, draws a traditional female outlook into the text: no demarcation of the self vis-à-vis the other or, in other words, an ability to identify oneself with many and much at one and the same time. And indeed, many women writers have worked in the genre – Kirsten Thorup in Denmark, Kerstin Ekman in Sweden, and Svava Jakobsdóttir in Iceland, to mention but three distinguished authors – but it is of course not an area reserved exclusively for women. On the contrary, it seems as if everything on which the fantastical draws –womanliness, orality, folk culture – the far “too natural”, has now entered a resolute marriage with the cultural sphere and has become the literary norm.

“And not far from this awful gang there lived a wealthy man with a daughter who was engaged to a stranger, a distinguished gentleman. Just before her wedding she had gone out into the forest and, all unawares, had wandered into the robbers’ lair […]. But at that very moment she heard voices and noise, and she hid under a bed. After a little while, a robber came in carrying the body of a young woman he had stabbed to death and, to her horror, the young woman under the bed realised that the robber was the very man she was going to marry. The robber tried to take a ring from the finger of the dead body, but he couldn’t get it off quickly enough so he took an axe and chopped the finger off with such a forceful blow that it flew down under the bed where the young woman was lying. Once the robbers had gone out thieving in the night, she picked up the finger and crept out of the lair. The wedding day arrived […]. And when they stood before the altar and the bridegroom was about to set the ring upon her finger, she held out the chopped-off finger – which she had concealed in a fold of her frock – and said: ‘That ring would no doubt be a better fit here.’ There was great commotion in the church. And he was instantly apprehended and executed along with the rest of the gang. The young woman entered a convent, where she ended her days. What a horrible fate that must be for a woman, concluded Marie, shivering in her light summer coat.”

Kirsten Thorup: Lille Jonna (1977; Little Jonna)

“In the past, she had been frightened of grey shadows that rushed off under the timbered houses, and she had been afraid of night-time, even when the nights were lightest. She had been terrified of the witches’ rings trampled deep into the grass, and not even during the daytime did she dare to go over to that side of the meadow. But her grandmother had told her that the rings weren’t made by dancing witches. The roe buck and his mate made the rings and the symbols of infinity when they were in heat, and they made them every single year in the same place… If his mate did not want to be mounted, then why didn’t she run right away into the woods? And if she meant to let him have her in the end, why did she rush away? What was forcing her to keep running? The witches’ rings had become even more frightening to Tora once she had seem them come into being.”

(Kerstin Ekman: Häxringarna (1974); Witches’ Rings).

“And the eyes of this petrified and cloaked figure sprang to life. They were like the eyes of a fox, darting to and fro between us. Then she fixed me so with her stare that the hood moved. Quite definitely. She sent me a message so compelling that I stood as paralysed, and in her eyes smouldered a fire that would burst forth in tongues of flame any second unless I did what she desired. The volition flowed from her. Bound in stone yet alive. I trembled to think what this terrible power would be like had it burst from the stone. And she was so versed in magic that I felt as if she transported this volition to me, compelled me to will something. I was meant to want to do something or other. And Gunnlöð held my hand tightly and began tugging at it. They had something to show me.”

(Svava Jakobsdóttir: Gunnlaðar saga, Forlagið Reykjavík 1987).

Translated by Gaye Kynoch