There is a great variety in the quantity of creative or academic material passed down to us from each of the approximately one-hundred-and-fifty illustrious writing women living in the Nordic region between 1500 and 1800. Alongside the extensive oeuvres – the works of Dorothe Engelbretsdatter, Anne Margrethe Lasson, Agneta Horn, Queen Christina, Birgitte Thott, Leonora Christina, Sophia Elisabet Brenner, and Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht, for example – numerous small extant oeuvres comprise perhaps a few poems, a book of genealogy, some drawings, a translation, a prayer book, a hymn book, and so forth. These are principally of interest by demonstrating, in virtue of their number, that in a very specific milieu in the Nordic region it was the custom for women to study and to write – all in all, indeed, to think. They each contribute to breaking down the picture of the intellectual/artistic woman as a one-off loner, as the exception who might cause some wonder but who can ultimately be disregarded when writing the history of Nordic culture and literature. There is even much evidence that they were not actually as lonesome as illustrations might suggest; an engraving for Frederik Christian Schønau’s Samling af Danske Lærde Fruentimmer (1753; Collection of Learned Danish Women), for example, shows a woman alone in a study. The learned women were linked by the ties of family; they often mixed with one another, being sisters, sisters-in-law, aunts, and cousins. They met at parties, festival days and sickbeds, and sometimes they worked together – perhaps researching the family history, in a teacher/pupil relationship, or as pupils at shared lessons. Their link to the intellectual world was not exclusively via men. Knowledge was also exchanged directly from woman to woman, in letters and face-to-face; there would seem to have been a subculture of learned women. Selected samples will serve to give us an idea of who these women were.

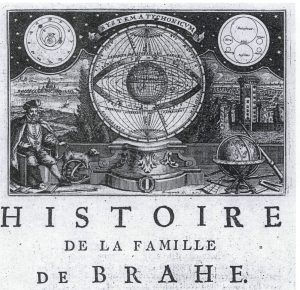

One of the earliest eminent, learned women was Sophie Brahe. She was born in 1556 or 1559 and died in 1643. In the annals of literature she is unfortunately most famous for one long poem she did not write: “Urania Titani” (i.e. From Urania to Titan), written in Latin, a fictional letter in which Sophie, alias Urania the Muse of astronomy in Greek mythology, writes to Titan, sun god, son of Uranus, the firmament. The poem deals with Sophie’s disappointment and longing while she waited for the return of her betrothed, the alchemist Erik Lange, who preferred to stay abroad experimenting on the production of gold. The poem is written in the form of an Ovidian heroid (an epistolary poem, purporting to be from a mythical heroine to her lover or husband, as written by the Roman poet Ovid) on the future husband’s protracted journey abroad. Sophie had been married before, to Otte Thott. He had died in 1588 and about two years later she – a widow and the mother of a son – became engaged to Erik Lange. The poem was written in 1594, but it was first published in 1668 by Peder Resen who believed, due to the poetic fiction in which Sophie had the role of narrator, that she was the author.

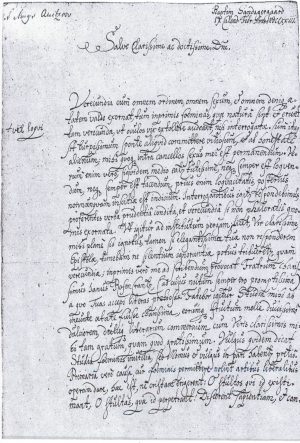

The author, however, was Tycho Brahe. In a letter written in Latin, dated 26 July 1594, and addressed to Thomas Craig, advocate, in Edinburgh, he referred to the poem as: “the elegy that I recently wrote for the sake of pleasant diversion, in my sister’s name, as an imitation of Ovid.” However, long after Resen’s publication of the poem, a copy was found with corrections made in Tycho Brahe’s handwriting. There has been some speculation that a poem written in Danish by Sophie Brahe might be lurking in the wings. This would seem unlikely. Tycho Brahe wrote a good many other fine poems in Latin and must have been familiar with the heroid genre, which was a popular form of Latin poetry in Europe around 1600. In Denmark, on the other hand, it had not been used before at all. The first Danish-language heroid we know about was written by Charlotta Dorothea Biehl, “Brev fra Waldborg Immersdatter” (Letter from Waldborg Immersdatter), in 1775 – almost two-hundred years after “Urania Titani”. What is more, Sophie could neither read nor write Latin. We find occasional references to Sophie Brahe writing poems, but any pen-on-paper poems from her hand have yet to be unearthed. It would seem to be Resen’s hastily drawn conclusion, jumping from the figure of Urania to the identity of her creator, that led to the assertion of Sophie’s authorship; for the time being, however, there is no evidence to refute the claim that the poem was written by the man who said he had written it.

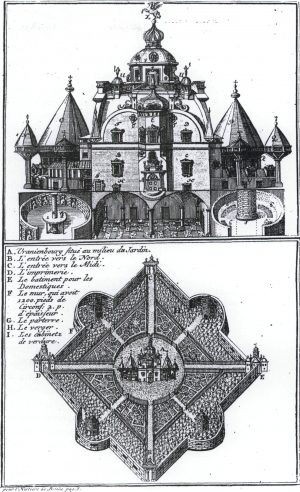

Even though, until proven otherwise, Sophie Brahe cannot be called a poet, she is still absolutely a “femina illustris” and is, as such, an early example of one of Denmark’s learned women. Her expertise was primarily in the areas of chemistry, horticulture, astrology and genealogy; in pursuing the two first subject areas she had also acquired medical knowledge. A far later source tells us that her older brother, Tycho Brahe, was considerably impressed by his younger sister; at the age of fourteen she was already helping him where she could in his first chemical laboratory, and she took part in the observations that led to his identification of a new star, which he named “Stella Nova”, and for which he became celebrated when he published his findings in 1573. Tycho Brahe thought her unique in the whole Nordic region. In the poem “Urania Titani” she is portrayed, undoubtedly deservedly, as an experienced astrologer. Tycho Brahe tells us that she put her knowledge of chemistry to use in the production of medicaments; she herself, in a letter to Margrethe Brahe, wrote that she “distil[s]”. We do not know for certain whether or not she actually engaged in alchemy and imagined that the alchemical art would lead to the production of gold, or whether she simply had to put up with the fact that her fiancé and later husband Erik Lange believed in it. For many years she engaged in horticulture; even when she was nearly eighty years old she received guests from abroad who had heard about her garden and wanted to see it for themselves.

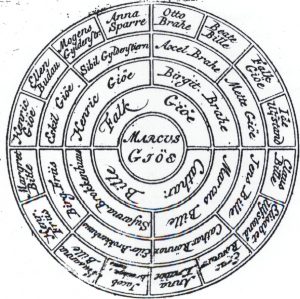

Finally, Sophie Brahe was a genealogist and was quite likely a role model for the many aristocratic women of the next generation who worked on their family genealogies, women such as her sister-in-law Margrethe Lange, Marie and Sophie Below, Anne and Birgitte Thott and a number of ladies from the Bille family. Sophie Brahe’s 900-page-long family book is a remarkable example of its genre. It can today be seen in the Lund University Library.

Anne Margrethe Qvitzow (1652-c. 1700) was renowned for her skill in Latin. She translated the first three books of Caesar’sGallic War; although never published, the translation is now kept in Karen Brahe’s Library along with another manuscript containing a moral-philosophical treatise on drunkenness. Lasternis Skrabe (i.e. Scourge of the Vices) is the title of the tract, written in her own handwriting and dated 1669, in both a Danish and a Latin version; the Latin, Strigilis Vitiorum, is most likely her own translation from the Danish. She was an aristocrat who had a good start in life, but nonetheless floundered in an ill-fated marriage, during which her fortune was squandered away, and ended up in abject poverty. Nothing is known of her life thereafter. Whether or not drunkenness was the cause of her own misfortune we do not know, but her treatise is deeply pessimistic in its view of a vice that is not only glorified by some people as a virtue, but that cannot be thrown off even by those who regret the hold it has on them. Her “elegy to Ove Rosenkrantz Axelsen til Raakilde”, written in Danish in c. 1685, is also kept in Karen Brahe’s Library. Finally, inserted in Otto Sperling’s work on the learned women is a short handwritten autobiography in Latin of Anne Margrethe Qvitzow, which was sent to Sperling in 1673 at his request, in which she gives an account of her ancestry.

At the age of fifteen, Anne Margrethe Bredal (1655-1729) wrote a speech in Latin on the occasion of the anointment of King Christian V. She worked as a teacher in the home of Birgitte Giøe til Qvitzowholm, and she was renowned for her learning. Two letters written in Latin are all that we have from her hand; in the one she writes about, among other topics, her marriage and studies: “My marriage lasted 17 years and was fruitful, producing eight offspring, one of the male sex, the rest little girls. This existence left me far too little time for my books. For I was kept away from my studies, partly because of my husband’s long-standing illness, partly because of the running of the household, which according to God’s will rested entirely upon my shoulders while my husband was ill. Yet I did occasionally seize an opportunity to indulge in study, and the Muses welcomed me back to their pursuits – me, I say, for whom nothing was dearer than the honey-sweet delicacies of the Muses. After full 17 years of marriage […] my husband’s life came to an end. I mourned his death, his deeply distressed widow, for three years together with the seven of my children still living. In the course of this quiet period of widowhood I resumed my studies, which had been somewhat slackly pursued during my lawful marriage, and I again formed a friendship with the Muses. Thus I turned with God’s will and the approval of my friends to a new marriage […].”

“To my mind, it is just as certain as can be that if women have loyal guides then they will just as often and just as willingly tread the path of learning as men. Alas, how often have I not heard my dear, sweet mother censure those who did not show her this path. She would most assuredly have reached the destination had she been led assiduously along the route of scholarship.” Thus wrote the learned woman Anne Margrethe Bredal in an autobiographical letter from 1673. “I love literature and will love it until the day I die,” she ended the second letter we have from her hand, dated 1703.

Cille Gad (1675-1711) came from Bergen, and we know that she too proved herself highly intelligent as a child. Her father taught her Latin, Greek and Hebrew, and it was said of her that “had she been a man, in her fifteenth year she could have been admitted to the university; and, furthermore, it is said of her that she could conduct a discussion in these three languages (being Latin, Greek and Hebrew) with any erudite man.” This information is taken from a letter to Otto Sperling written by the hymn writer Anna Reimer, and she goes on to relate how, at the age of twenty-nine, Cille Gad had been made pregnant by a sailor from a Dutch ship en route to the West Indies. According to one source, she concealed her pregnancy and gave birth alone. Another source said that she had arranged to join her future husband later, but had given birth prematurely. Whatever might actually have happened, soon after the birth she was found with a dead baby; she was then accused of infanticide. This she denied, saying that the baby had been stillborn. True or false, she was sent to trial, found guilty and condemned to death. She was then held for some time in a prison on an island off Bergen. Her father fought for her release, and Anna Reimer wrote to Otto Sperling and asked him to intercede on her behalf. While in prison, Cille Gad was informed that she had been admitted into Sperling’s collection of learned women. She expressed her thanks for the honour and again declared her innocence. Following an exchange of letters between them, written in Latin, Sperling did indeed intercede on her behalf. On 3 September 1707 he wrote to the king! One of his arguments was that there had been many people in the house when Cille Gad had given birth, but no one had heard the sound of a baby crying, which would suggest that the baby was stillborn. It had yet to be proven that she had killed the infant, and the first judge had actually acquitted her. As a final argument, Sperling wrote that: “this person has pursued academic studies and has in every way made good progress in her Greek and Latin languages […] so it would be the utmost shame were this woman to end her days so wretchedly.”

Some of the letters from Cille Gad to Otto Sperling have survived, among them two poems written in Latin during her imprisonment. She was finally acquitted on 6 April 1708. She then moved to Copenhagen with her father, where she remained until she died of the plague in 1711.

In the throng of individual women who have attracted favourable attention through scholarship and writings, the occasional umbrella emerges, covering a whole group of studious women. These help towards an understanding of how it was at all possible for so relatively many women to break away from the normal lifestyle of their gender. More often than not, family relations can be identified as the unifying factor. There is also, however, at least one example of a clear-cut ‘women’s organisation’, this being the Odense adelige Jomfrukloster (a secular convent home for unmarried ladies of rank, situated in Odense on Funen): a treasure, a very special and rare pearl, for all to see in the centre of Denmark. Unpolished today, but still unspoiled. The “Jomfrukloster” was established in 1716 by Karen Brahe. It was the fourth in a series of seven homes for unmarried ladies of noble birth set up between 1699 and 1749; in order: Roskilde, Gisselfeld, Odense, Støvringgaard, Vemmetofte, Vallø and Estvadgaard. The privileges of the Danish nobility had been steadily reduced since the imposition of absolute monarchy in 1660, and an unmarried daughter of noble rank could easily find herself in financial straits, which her family might not be in a position to alleviate. This is one of the reasons for the sudden rise in the number of convents set up around the year 1700.

Odense Jomfrukloster will be highlighted here, at the expense of the other secular convent homes, because of its special cultural status afforded by the founder, Karen Brahe (1657-1736), and her maternal grandfather’s sister, Anne Giøe (1609-1681). The ‘convent’ was more than an institution for aristocratic ladies of meagre means. It was a centre for learned women.

The convent home was established by and for women. The institution was firmly rooted in Christian soil. There was room for eight resident unmarried noble ladies, and they could use the library to study in harmonious and aesthetic surroundings amid the many fine portraits and paintings that were gradually accumulated. Today, the book collection is housed at Roskilde Priory, where the majority of the portraits also hang.

The aristocratic spinsters Anne Giøe and Karen Brahe are both obvious candidates for the list of Denmark’s learned women and they are also both named in the gynaecea, even though neither of them seems to have left any extensive written oeuvre. The library was atypical given that the majority of works in the collection were written in Danish and a large proportion of the texts were written by women. When intellectual men built up private book collections, their main interest was often directed abroad. Latin was an important tool in their studies, because the greater part of the international scholarly literature was written in Latin. Both non-fiction and fiction were chiefly written in Latin, French, German and gradually also in English, while literature written in the national language was left somewhat high and dry.

Anne Giøe was thus, in a sense, going against the tide when she built up her library with emphasis on works written in Danish. She might not have been skilled in Latin, and she might not have shared Birgitte Thott’s ambition of being at the centre of events, but, as Albert Thura wrote: Anne Giøe did not simply collect books, she also read them.

Anne Giøe must have known Birgitte Thott very well. Birgitte’s husband was Anne’s brother and she had grown up with him at Rosenholm Castle in the scholarly environment promoted by Holger Rosenkrantz. Anne’s father, Henrik Giøe, had died in 1609 when she was an infant; her mother, Birgitte Brahe, died two years later. From the late 1620s until 1649 she lived at Hvidkilde Manor near Svendborg with her brother Falck Giøe and his wife Karen Bille. In the period from 1649 to 1653 she lived with them in Sorø, where Falck had been appointed a professor. Sorø was but a stone’s throw from Birgitte Thott’s manor, Thurebygaard, where Anne had been born. Widow Thott and Miss Anne must have seen one another quite frequently during this period. Birgitte Thott’s mother, Sophie Below, was known for her fine family book, which her daughter, also called Anne, took over and continued working on; Birgitte Thott later revised the manuscript and equipped it with a grandiose introduction, which tempered the inevitable look of a rough draft that goes with the phase of collecting material. Writing Brahes, Giøes, Thotts, Belows, Billes, and so forth, knew one another in criss-crossing constellations. The idea of a shared library was just around the corner.

Anne Giøe started her book collection at an early age, and it accompanied her all her life as she moved from manor to manor. At her death, it passed into the keeping of Karen Brahe, someone who would love, respect and derive benefit from the library and make sure it was not dispersed. Karen Brahe transferred the books to her convent home as soon as it was up and running, and she continued to expand the collection.

In the history of “the learned women” Karen Brahe’s Library has no equal. For most women the path to the library had of necessity to go via a man, a father or a husband, who also had some say in which reading matter would benefit their women. Karen Brahe’s Library was stocked by and for women. The collection was valuable and sought after. Interested men could obtain permission to visit the Library, and they were well treated once there. They could commission a copy of a manuscript or a printed book, but the material in the Library was not for sale.

The Library has not been enlarged to any substantial extent since Karen Brahe’s death. Today it consists of approximately 2000 Danish-language books, of which approximately 1000 come from Anne Giøe. One way in which Karen Brahe supplemented the collection was by purchasing books from Frederik Rostgaard’s Library. There are fifty-four books dating to pre-1551; seven of these are, as far as we know, the only extant copies of the works concerned. Of the manuscripts, the collection of sixteenth-century folksongs known as “Karen Brahe Folioen” (Karen Brahe’s Folio Manuscript) must be mentioned, as should Leonora Christina’s Hæltinners Pryd (Adornment of Heroines), Susanne Giøe’s translation of the first section of Vives’ De institutione feminae Christianae (Om den kristne kvindes opdragelse) (The Instruction of a Christian Woman), and Birgitte Thott’s Om et lyksaligt liv (On a Happy Life). The Library also contains a collection of over 400 funeral sermons, of which many have never been published, and a fine collection of book bindings, including what is known as a concertina binding.

If we pick out the Nordic women’s literary oeuvres and gather them together, big and small, we see the Nordic region in fine bloom, with committed, moving, keen, sincere, quality writing often arranged in bouquets around a scholarly family, a manor or a convent. A female consciousness and a literary aesthetic equal to those found elsewhere in Europe is clearly present in the work of the Nordic “feminae illustres”.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch