Hagar Olsson (1893-1978) may have been dubbed the “apostle of the life force”, but her first novel was entitled Lars Thorman och döden (1916; Lars Thorman and Death).The book was brought out the same year as Edith Södergran’s first poetry collection. According to literary historians, the twin events marked the birth of Finland-Swedish modernism – Gunnar Brandell called it “a remarkable phenomenon […] that fuelled modernism in Sweden as well.” Olsson, aged twenty-three, and Södergran, aged twenty-four, did not know each other yet. They became friends in 1918 after the publication of Södergran’s Septemberlyran (1918; The September Lyre).

Their point of view in 1916 was somewhat retrospective: their works reflected fin de siècle pessimism, the existential crises brought about by World War I, and the sceptical literature by loafers and men-about – town that was in fashion at the time.

A man “with cold eyes” frequents Södergran’s work with striking regularity. In addition to the well-known “Dagen svalnar” (The Day Cools), he appears in “Oroliga drömmar” (Uneasy Dreams): “There is something heavy, immobile in his inner being, … wings bear him into the land where all that he does is in vain, / into the land of empty and useless days far away from fate …”

Olsson’s novel can be interpreted as the story of such a man, who has lost contact with the meaning of life. But she crosses an important threshold by demonstrating that such weariness and resignation is not a sustainable foundation for creating art, which requires fieriness, power, and substance, the ability to connect with “the absolute”. Proceeding from a venomous survey of the decadent turn of the century with its supercilious, rambling cynicism and self-absorbed mood of annihilation, she advances the hope of a new culture based on inspired human community in a transformed world. That is the modernist challenge in Lars Thorman och döden.

Many experiences of the weary, disillusioned hero come from the life of the author herself. Her writing reflects the sense of rootlessness that originated in her childhood. The middle-class, Christian household harboured conflicts, disagreements, and discords that made her prone to depression and existential brooding. After a showdown with her father, who also had three sons to support, she obtained the money to enrol in the humanities curriculum at the University of Helsinki, but thought the courses she took to become a language teacher were meaningless.

A Thrilling Encounter

Dagens Press (The Daily Press)hired Olsson as its literary critic in 1918, providing her with a venue to wage her celebrated campaign for ‘modernity’ in art and literature. Her most significant initiative was the launching of Södergran into public awareness.

The crucial importance of Olsson’s friendship for Edith Södergran, who lived an isolated life, has been frequently emphasised. However, Olsson’s evolution as a writer was equally dependent on the relationship. The creator of Lars Thorman with all his anxiety and mortal longings found someone who experienced death as a constant presence, but could nevertheless exclaim with conviction: “What do I fear? I am a part of infinity. I am a part of the cosmos’ great strength …”

Olsson was drawn into the charmed circle, and it was not long before ‘I’ turned into ‘we’:

“A magic spell came over us and left us with the feeling that anything was possible at any time. The future glowed within us and made us impatient; its seductive and terrifying crown would one day be ours. We were unknown and poor and lived in a remote corner of the world, and yet we felt like princes. Our treasure was wrapped in the hope that hovered over a devastated world like the hands of angels and pointed to a new humanity.” (letter by Södergran).The letter stakes out Olsson’s entire literary project, its faith in the life force, the power of the spirit to transform the world, and the artist’s holy calling, “with responsibility for all of humanity.”

No book has ever revealed more about Olsson as a person than Ediths brev (1955; Edith’s Letters; Eng. tr. The Poet Who Created Herself), which she published after overcoming heavy inner resistance. Her reticence, clearly expressed in the preface, to dust off the letters reveals the deep impact that the relationship had made on her life even though it only lasted from 1919 until Södergran’s death in the early summer of 1923. With its detailed notations by Olsson, the book

is rather like a tragic novel that traces the dissolution of a deeply loving friendship. Olsson was plagued by feelings of guilt early on for all the visits she had neglected, the letters she wrote less and less often despite Södergran’s eternal plaint: “Have you forgotten me?” Olsson’s notations explain that she was weighed down by work, that she was frequently ill, and that her family needed her during the holidays.

“No one had heard anything like this before. Here was the consciousness of modern humanity suddenly exploding into Finland’s provincial cultural milieu which, despite world war and civil war, was still completely anchored in the past and imagined that it retained unchallenged possession of its territory. It is both tragic and comic to remember how incapable readers were of understanding such language at the time.”

(Olsson writing about Edith Södergran’s Septemberlyran in Ediths brev)

A Deeply Involved Literary Critic

Olsson had not yet found her voice when she wrote her first three prose works – Lars Thorman och döden, Själarnas ansikten (1917; Faces of the Soul), and Kvinnan och nåden (1919; Woman and Grace). As often as not, her tone and vocabulary were reminiscent of the literature she was fond of attacking: the pretentious echo of the 1890s. But her reflections on other authors were masterly from day one. She could find words to describe even the most subtle nuances, the essence of the work she was reviewing, the pulsating individuality of a writer. She demanded commitment from both authors and critics. One of her essay collections was entitled Möte med kära gestalter (1963; Meeting with Dear Figures). Her portraits of writers seek to capture the meeting itself, the encounter between a reader and the printed page, a process that is every bit as fragile and crucial as that which goes on between two people.

Much has been said about the impact of Olsson’s analyses on literary history. As a leading critic for a large Helsinki newspaper, she was in the catbird seat to propagate modernist ideas. Along with Elmer Diktonius, she was also the motive force behind the radical cultural magazines Ultra (1922) and Quosego (1928-1929), which became forums for young writers in Swedish, Finnish, and other languages.

Ny generation (1925; New Generation) is a collection of previous literary essays. The thin volume with its typical 1920s cover by Wäinö Aaltonen – the man Olsson was living with at the time – retains its vitality and relevance to this day, yellowing pages notwithstanding. Her introductions to the writings of difficult authors like James Joyce and Guillaume Apollinaire are extraordinarily insightful. She has a knack for putting her finger on the groundbreaking personal and revolutionary aspects of their styles and worldviews.

Having incorporated feeling, empathy, and intuition into the genre of literary analysis, Olsson was contemptuous of the intellectual hair-splitting that she found in much of the criticism written by her academic, male colleagues. A long, prominently displayed article that she wrote for the newspaper Stockholms Dagblad in 1928 lambasted Professor Fredrik Böök under the ironic title, “Den ofelbare svenske kritikern” (The Infallible Swedish Critic). This attack by a young woman, aimed at the foremost authority on Swedish culture, spurred a boisterous debate and exposed fundamental conflicts between traditionalism and modernism, in Sweden as well.

Theatre of Revolt

Olsson achieved the most significant formal renewal in her dramatic works. Over the course of four years, she wrote three plays that broke with the naturalist tradition: Hjärtats pantomim (1927; Pantomime of the Heart), S.O.S. (1928), and Det blåa undret (1931; The Blue Wonder). The various roles are embodiments of power in the world she saw around her. The characters are more like carriers of ideas than real people. Like her prose works, the plays zero in on the psychological forces behind appearances and external events.

Olsson was largely interested in creating political theatre that preaches and agitates. Her goal was to raise urgent questions about war and peace, dictatorship and democracy, oppression and revolt. Hjärtats pantomim is about the seductiveness and intrinsic destructiveness of capitalism. “Everybody wants money. They never think about anything else, they live only for it. Money. And more money.” Love, on the other hand, is a dynamic and rejuvenating force.

S.O.S., which goes head to head with the arms race and chemical warfare, is eerily evocative of today’s weapons trade and nuclear threat. The protagonist is a weapons manufacturer who becomes a pacifist when he realises the consequences of his actions.

Det blåa undret mirrors the tension between Communism and Fascism in the Europe of the time. It was first performed in Helsinki in March 1932, less than a year before Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor. A young woman is a socialist, while her brother is a fascist. In the final scene, they confront each other at a street demonstration. A self-assured female figure steps to the front of the stage and presents the message of the play. The revolutionary drama stemmed from Olsson’s acquaintance with the group of feminists that ran the Women´ s College for Civic Training at Fogelstad.

The New Woman

The theme of “the new woman” and associated issues was more conspicuous with each novel Olsson wrote in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Mr Jeremias söker en illusion (1926; Mr Jeremias Searches for an Illusion) is about a weary contemporary man trying to squeeze a little meaning out of life. In the expressionist novel På Kanaanexpressen (1929; On the Canaan Express), however, a disheartened male author undergoes a transformation in the first chapter when he meets a young woman named Eaglet: “She seemed to have been created for wings – for high altitudes – for solitude.”

The Eaglet character in På Kanaanexpressen was based on Toya Dahlgren, Olsson’s partner from 1928 until she died of tuberculosis, like Södergran, in 1932 at the age of twenty-two.

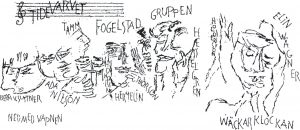

Det blåser upp till storm (1930; A Storm is Brewing),Olsson’s next novel, cedes the stage to an independent, rebellious upper secondary school student by the name of Sara. She is the first narrator to appear in Olsson’s prose works. The book was runner-up in the 1930 competition for the best contemporary Swedish novel sponsored by Natur och Kultur publishers. The award aroused widespread interest in Sweden, and Olsson was invited to make a lecture tour. She called her presentation “Förräderiet mot ungdomen” (The Betrayal of Young People). While in Sweden, she became acquainted with the group that published the radical feminist magazine Tidevarvet and with the Women´ s College for Civic Training at Fogelstad. “Förräderiet mot ungdomen” appeared in the magazine, which continued to publish her articles throughout the 1930s.

Olsson’s association with the Fogelstad group whetted her appetite for women’s issues. In the summer of 1931, she held a lecture series at Fogelstad entitled “Militant Femininity”. In her view, society had to be rebuilt from the ground up: “Women cannot be emancipated within the old social structures, which rest entirely on the dogma of male rule.” She ended with the appeal: “A woman who does not rebel is not a woman, only an appendage to men.” Her theses were doubtlessly a bit too radical for many of her listeners. But headmistress Honorine Hermelin and Ada Nilsson, the controlling editor of Tidevarvet, were delighted, marking the start of lifelong friendships. Olsson carried on a lively correspondence with Hermelin that was reminiscent of her exchange with Södergran a decade earlier. The letters tended to focus on Olsson’s writing career. Hermelin read her manuscripts and suggested changes, sparing with neither criticism nor praise. She mourned with Olsson when her young partner, Toya Dahlgen, died of tuberculosis, reawakening the trauma of Södergran’s passing ten years earlier.

Chitambo (1933)describes the difficulties associated with refusing to remain “an appendage to men” and becoming an independent individual, both emotionally and intellectually. A woman’s coming-of-age story, it is not about reforms or the struggle for equal rights. Instead, the themes are power and powerlessness, the pain of inner emancipation, the soul’s rebellion, and the struggle of the oppressed for wholeness and dignity.

The protagonist Vega Maria Eleonora Dyster (her last name means gloomy) is born, like Olsson herself, in 1893. The fight over what to name her long affects her search for a sustainable female identity. One of the chapters is entitled “Conflicting Names Trouble My Soul”. Her father has her baptised as Vega after A. E. Nordenskiöld’s famous ship. “He took it for granted that I was born to greatness and knew just how to inculcate the same foolish fancy in me.” Browbeaten and disappointed by life, her mother wants to name her Maria (Mary), evoking the self-sacrificing concept of womanhood. To top it off, she is also given a third name (Eleanora) at the actual baptism ceremony. Going to see Henrik Ibsen’s Et dukkehjem (1879; Eng. Tr. A Doll’s House) one evening, she identifies with Nora, the bold and wilful rebel: “That was when I decided to be a proud, free woman. I would never marry, never succumb to a man’s charms.” Ironically, she meets the love of her life right after that. Not until the man abandons her and she attempts suicide can she begin to construct an identity for herself. To do that, she needs a language of her own. She has experienced the horror of annihilation; when she returns to the world of the living, she listens only to herself for the first time.

Teenage girls who revolt against the fossilised lifestyles of their parents abound in the books of short stories with which Olsson concluded her career: Hemkomst (1961; Homecoming), Drömmar (1966; Dreams), and Ridturen (1968; The Riding Trip).

Alienation from the Modern World

World War II profoundly challenged Olsson’s faith in the future. After having fought so passionately for peace and humanity, she was left with “an emptiness in my heart that nothing in the world could fill.” Jag lever! (1948; I’m Alive!) is a confession of her horror when faced by Nazism, violence, killing, and the concentration camps. Her essay is a pained critique of civilisation. Her later books are frequently about people who feel alienated from the modern world. Her works of the 1940s – the novel Träsnidaren och döden (1940; Eng. tr. The Woodcarver and Death), the play Rövaren och jungfrun (1944, The Robber and the Maiden), and the memoirs Kinesisk utflykt (1949; Chinese Outing) contain a portentous mystique of life and death that casts a spectral light over the words.

Jag lever! contains two sweeping, penetrating essays – both of which had been written earlier – about authors with whom Olsson felt a deep affinity: Agnes von Krusenstjerna and Cora Sandel.

Kinesisk utflykt, a deeply personal and original book, combines memories with reflections about the present. A subjectively perceived underworld becomes the framework for recalling the days of her childhood, from which she glimpses the shapes of her parents in a redemptive and clarifying light. Finally she finds her most beloved friend, lost to her for these many years:

“Oh, this back, its narrow, protectively hunched shoulders, they were eternally branded in my consciousness; they could belong to only one person in the whole wide world. Something that had been deeply buried wanted to push its way up, a pain so great it would have torn me to pieces had I not hid it in the ground, far beneath the soil in a flowerless grave.”

The passage brings to mind a well-known line in “Dagen svalnar” (The Day Cools) by Södergran: “[…] take the longing of my narrow shoulders”. In Olsson’s fantasy, the long-lost friend sends the narrator a painting of “a lunar landscape bathed in incomprehensible light” – a memento of “Landet some icke är” (The Land That Is Not), Södergran’s magical poem in which “the moon tells me in silver runes” about death, which is no longer frightening, but opens the door to “the land where all our wishing is marvellously fulfilled.”

Translated by Ken Schubert