Elsa Gress’s (1919-1988) pen is, in her own word, heretical. It castigates and breaks with smug Danish mediocrity, and her rhetorical question “is anyone listening” is a critical highlighting of the Danish ‘deafness’ and a reflection of her personal experience of feeling like the odd one out, of feeling misunderstood, of speaking but not being heard.

The root cause and partial explanation for the repeated theme of being left out can be found in Elsa Gress’s first book of memoirs, Mine mange hjem (1965; My Many Homes). We are told that Elsa awoke to an awareness of the world via the heavy furniture of her childhood home with its “carvings, flutings, twisted columns, and polished panels, which a child can use as a mirror and see the world strangely distorted.” Elsa looks at her reflection in a Chinese vase, which is first an object of fascination, but which turns out to be cold and hostile when the child hugs it: “It was a shock, which has undoubtedly followed me and marked me to this very day.” This early memory of being attracted and being rejected was to prove symbolic for Elsa while growing up within and outside the unconventional Gress family – constantly moving from home to home, going steadily down in the world.

A feeling of exclusion also comes across in her memories of clever and beautiful older sister Lily, whose pious religiosity brooked no competition. Lily’s premature death aged nine kept her forever in the role of idealised myth she had already filled in life; this made it impossible for Elsa to escape her dead sister’s shadow and receive sympathetic attention from her mother, who remained distant and frozen over the death of her eldest daughter.

Elsa Gress shared the feeling of exclusion with her brother, Palle, who committed suicide at the beginning of World War Two, shortly after their mother died. The intimate, almost erotically-tinged relationship with her brother explains Elsa Gress’s erotic fascinations. Her brother’s troubled disposition and violent mood swings are not only found in a number of the male characters in her works. In her second volume of memoirs, Fuglefri og fremmed (1971; Fancy-Free and Foreign), where Elsa Gress writes about her personal erotic fascination as a mixture of aversion and desire, sexuality is also associated with her strong feelings for her late brother. Eroticism that grows out of ambivalence is given clearest form in the novels Jorden er ingen stjerne (1956; The Earth Is No Star) and Salamander (1977).

In her third book of memoirs, Compañia I–II (1976), the enforced feeling of otherness during her childhood and adolescence is seen as the background against which she establishes herself in the role of “professional outsider” – a position she stresses is necessary, but which she also, ironically, protests against. Her writing career is characterised by the clash between wanting to maintain a marginal position – being an outsider, who sees more clearly – and wanting to be heard and understood.

Elsa Gress was made a member of Det danske Akademi (The Danish Academy) in 1975. In the Academy’s septennial publication En bog om inspiration, 1974–1981 (A Book on Inspiration, 1974-1981), Elsa Gress gave her version of how 1970s’ Marxism viewed art, and she gave vent to her indignation:

“In the last couple of decades, this foolish inartistic, or directly anti-artistic notion of inspiration as Romantic, and therefore ‘bourgeois’, phenomenon, has been thrown together in profane mêlée with the ‘Marxist’ ideas that art is all in all a bourgeois and therefore sinful phenomenon, which in the classless society of the future will be replaced by ordinary folk dancing on the village green and equal creative opportunity for all.”

Between Life and Friends

“I always write memoir”, states Elsa Gress in her collection of essays Blykuglen (1984; The Lead Bullet), “but sometimes I use the real names and the real events.” Drawing boundaries between reality and fiction was to her illusory. The result is an oeuvre in which the same stories, experiences, and memories are repeated in various forms. People from her private life can be recognised – often down to the tiniest details – in her fictional characters.

Her preoccupation with language, with its “nuances and its changeability”, does not result in reverence, but more of a desire to maintain the value of language and to break open its boundaries. Thus the debating style, familiar from her many collections of essays, often breaks into the novels as a kind of educationalisation of the writer’s intention, as a not always successful combination of an essayist tone and a literary tone. The memoirs Mine mange hjem and Fuglefri og fremmed play the strongest artistic card – also as fiction – in Elsa Gress’s body of works. The polemic tone, which spreads from her extensive essay output to her fictional works, is caused by a constant and impatient desire to enter into a dialogue with the reader – as is apparent in, for example, part of her collection of short stories Habiba (1964). Here it is clear that the most successful stories are those furthest removed from Elsa Gress’s own easily recognisable alter egos – as in “Skål for en lunefuld dame” (A Toast to a Capricious Lady), which describes the twist of fate when a young boy is imprisoned in a concentration camp because of his Jewish-sounding name and is saved – in another twist of fate – by a fellow prisoner.

The novels, on the other hand, closely follow Elsa Gress’s own development and experience and act as a form of twin text to the memoirs and vice versa. Her debut novel Mellemspil (1947; Interlude), which received the literature award Schultz’ Litteraturpris that same year, describes the feeling of detachment and loneliness experienced by a young Danish woman visiting London after the Second World War. The shadow of death from the war years mingles with a sense of loneliness, loss, and inner despair. The personal tone, in which “any resemblance to real persons was intentional”, as she later writes in Fuglefri og fremmed, is an attempt to create a “truthful documentation of inner circumstances, and of the outer circumstances that determine them”.

Albeit an archetypical Dane, Elsa Gress finds a distinctive perspective on the Danes via that which is different. This outer, alienated vantage point, which she gradually acquires over the course of her childhood, is intensified by the distance generated by travel. In Fugle og frøer (1969; Birds and Frogs), she describes how travel is necessary “for the development both of personality and of abilities, and at the same time something that has to be endured, something that is fun to remember but troublesome to undertake.”

Her ambivalent attitude to the US, as demonstrated in the novel Jorden er ingen stjerne, is perhaps illustrated most clearly in the essay “Rosen blusser alt i Danas have” (Rose is Blooming Now in Dana’s Borders) from Om kløfter (1967; On Chasms), where the “chasm” between the US and Denmark becomes unintentionally parodic. An euphorically nostalgic stay during World War Two on the banks of lake Arresø – which gives, despite the shadow of war, a picture-postcard image of unspoilt Danish countryside and solidarity between friends, symbolised by a couple of chipped mugs of wartime tea made from dried apple leaves – is juxtaposed with a heat-wave summer in an LSD-filled, dysphoric, and violent New York some time in the 1960s. The problematic comparison illustrates how the nightmare version of the US can also serve as a stabilising factor for Danish identity.

During the German occupation of Denmark in the Second World War, Elsa Gress was active in the resistance movement while also studying for a master’s degree in Comparative Literature; she wrote a dissertation, awarded a gold medal, on Engelsk æstetisk kritik fra 1680 til 1725 (English Aesthetic Criticism from 1680 to 1725). In 1945 she made her publishing debut with a collection of essays, Strejftog (Raids), the first of what was to be a long list of critical books dealing with society, art, and gender. The distinctive Gressian mixture of genres caused Poul Henningsen to declare that “by intellect [she] is a scholar, but by disposition she is an artist”.

Mythology of the Artist

Elsa Gress sees the artist as a special person who will always be closer to the truth, and this is the position portrayed in her two final novels, Salamander (1977) and Simurghen (1986; The Simurgh). The salamander is a mythological reptile that can withstand fire, and which symbolises “somebody who enjoys and lives in great heat”. Stage director Roy Roscoe is one such fiery spirit who, with his uncompromising artist’s temperament, consumes the people in his life. Brilliance but also brutality make up the artist’s Janus face; hatred and love, desire and rejection constitute the two sides of the same coin. Like Judith in Jorden er ingen stjerne, the female lead, Lisa, is almost masochistically attracted to the strong male type, and she is willing to lay herself open to the degradation that comes with loving a great artist. Lisa has to acknowledge that the intense, but brief, nearness causes absence, loss, pining, and pain. But “art and love always upend norms, expectations, illusions, reality.” Ironically, behind Lisa’s uncompromising search for art and love there is a husband who (mostly) with gentle understanding looks after the children and remains a fixed point in her life.

Of Elsa Gress, Poul Henningsen wrote:

“She is mistress of the art form that is the definition of all art: to attach greatest importance to the essentials and be indifferent to the non-essentials. That is the way in which she has arranged her life. That is the way in which she has built a home around her consisting of husband and children and parrots and guests, where everyone gets up and goes to bed as and when suits them […] She lives likes she thinks she should… She writes like she lives.”

Accounts of art, love, and death continue in Simurghen. Here Elsa Gress focuses on group painting, a collage of the circle of friends around Hugh, the painter, and his wife Judith, a writer. Between the initial rough sketch for the painting in 1978 and the application of paint in 1986, the friends gradually meet death in more or less violent ways: murder, suicide, accidents, death from cancer, stroke, and heart failure. The mythical figure of the Simurgh, which is painted into the final process of the artwork, becomes the emblem of the presence of death in life. It is a celebration of the “continued life of the dead in the consciousness of the living, and the connection of the living with the dead”, as is gradually unveiled through the real and imaginary ways in which the characters intervene in each other’s lives and consciousnesses.

Judith describes the bird as:

“the visible symbol of the ineffable and unattainable, in which we all have a share and which has a share in all of us.”

Although the novel is structured around the creation of a painting, it is clear that the writing is the crucial factor: a fragment, which Judith has carelessly left lying on a pot in the kitchen and which her painter husband finds and keeps, can be read as a manifesto:

“It begins in the language, in the words with their heavy burden of accumulated experience of sorrow and delight […] A picture that says more than a thousand words is a gift, but a greater gift is a word that says more than a thousand pictures. Language is us, in truth and falsehood, love and hatred, courage and fear.”

Simurghen (1986)

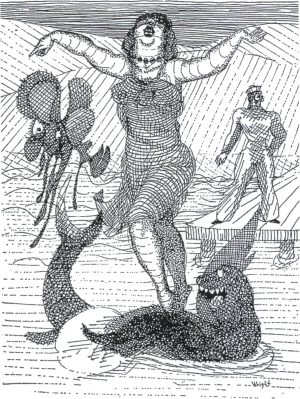

Elsa Gress was always seeking inspiration from visual art forms, theatre, film, painting, and sculpture – not as a contrast to language, but as a dialogue in language and with language. Her fascination with visual art is perhaps given its finest articulation in her play Den sårede Filoktet (1966; Philoctetes Wounded), which was filmed for television by Danmarks Radio (Danish Broadcasting Corporation). Inspired by Nicolai Abildgaard’s painting of the same name, the play gives a clear exposition of the problems faced by art and the artist as being fundamentally a matter of non-simultaneity. Abildgaard is here the symbol of the genuine, uncompromising artist faced with oblivion or lack of comprehension. His painting Den sårede Filoktet depicts the isolation and pain to which the artist is reduced by an uncomprehending and brutal world that cannot recognise true genius when it sees it. The mythological picture becomes not merely a metaphor for the fate of the artist – wounded, but vigorous – but also a picture of the concept of the artist that Elsa Gress advocates. The true, uncompromising artist becomes a marginal figure in a society that cannot or will not have truck with contradictions, otherness, strangeness. Carl Th. Dreyer, Asta Nielsen, and Karen Blixen join Abildgaard as the perfect examples of true artists who are not understood by the official Danish cultural world, and Elsa Gress makes them identification figures for her personal experiences of alienation and marginality.

Karen Blixen was one of Elsa Gress’s Danish ‘household gods’. In a letter to Anders Westenholz she explains her view of Blixen and motherhood:

“She quite clearly used, and knew she did, ‘her’ natives as substitutes for children, but there can be no doubt that she felt the void eating away inside her, and that her words to the contrary are rationalisations of the given situation. Writing is not on any level a substitute for having children, and it was not ‘humbug’ when at the end of her life she told Jonna Dinesen that it was all very well being a famous author, but the happiness – and the unhappiness – of being a mother it was not.”

Feminism or Humanism

Polemic and heresy are also part of Elsa Gress’s approach to the women’s struggle, which she to some extent anticipated with her discussion book Det uopdagede køn (1964; The Undiscovered Sex). The book was intended to step in “where the other participating ladies fall silent, from ‘modesty’, from ignorance, from circumspection” – to step in by involving the personal element. Although she is in agreement with Simone de Beauvoir’s views, as expressed in Le Deuxième Sexe (1949; The Second Sex), about female gender being socially constructed, she criticises her for omitting a personal investment in the analyses, for using a masculine form of argumentation, for taking cover under case stories and indulging in abstractions. Woman is not the second sex, states Elsa Gress, she is the undiscovered sex, whose potential is not yet visible in the prevailing “single-sex society”.

In Det uopdagede køn (1964; The Undiscovered Sex), Elsa Gress states:

“Woman as such is not the mystery, albeit many generations of men have so believed and – the ones who are writers – voiced. The woman, the individual human being, is. To which one can but add that nor do we get closer to the man as person and human being by analysing the concept of Man. He is just as mysterious as the woman.”

In line with her dismissal of abstractions in the gender debate, Elsa Gress dishes out sharp criticism of “group treatment” of the sexes. The women’s issue is a humankind issue, the liberation of women is the liberation of humankind, humanism is more important than feminism. “There cannot be much wrong at all with the one sex without something equivalent being wrong with the other.” The route to the “ultimate emancipation” is therefore that of double liberation and the rendition of both sexes as humankind. It is dangerous, she maintains, to claim that women have special “superior intuitive ability” because this kind of idealisation of femaleness, if followed to its logical conclusion, will turn into pure masculinism and thus to the complete opposite of idealisation: devaluation. It is therefore of no use to speak of ‘woman’ as abstraction, to make her a mystery that has no relation to women in real life. Elsa Gress herself, however, does not sidestep abstractions and generalisations: she asserts that women are not merely bearers of culture, they are the very point whence culture rises. It is thus woman who is responsible for the origin of language. Language, she points out in her essay “Kulturbærerne” (The Bearers of Culture), twenty years after the publication of Det uopdagede køn, stems from mothers’ need “to impart experience to the next generation and to refer to things that were not there, but that might happen or had been there”. This view of the mother language does not mean she advocates an actual women’s culture, but that she arrives at a quite different view of motherhood than that reached by Simone de Beauvoir. Elsa Gress considers Beauvoir’s analysis of motherhood as enforced societal role to be mistaken because it does not include the mother’s biological and personal experience of consummation.

That a woman writer, and particularly a woman who participates in the public debate, will be subject to prejudice is, in Elsa Gress’s view, a fate common to women who pick up a pen. Her own works were either praised as being “just as substantial and perceptive as a man’s” or she was called “acutely malicious as only an intelligent woman can be”. However, not being invited to the top table allows women the opportunity to find their own uninhibited voice, and they can thus “say things directly and effectively”. In her preface to Det uopdagede køn – in order to reassure the reader and as an ironic gesture in response to fear of the woman writer – she comments tartly on the book’s cover photographs “of the authoress, and one of her with her family”: the photographs were there to prove that the writer was not “a monstrous creature, an uncommonly ugly or disagreeable or perverted female person […] the reader [must] be reassured that they will not be subjected to bluestocking nonsense, and that the authoress is neither exorbitantly flat-chested, nor arrogant, nor sexually deviant.”

In Det uopdagede køn it is art that gives the woman status as human being, as is the case with so many of the issues Elsa Gress examines and describes. “It is inherent to the essence of art – as well as to the nature of its practitioners – that it is a field in which notions of a totally superior and a totally inferior sex simply cannot thrive.” Art is always “on the side of Romeo and Juliet”, because it is a matter of erotic tensions between the sexes as equal individuals. However, she highlights male writers and artists as “women’s voice”. Hester Prynne from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850) and Jeanne d’Arc in Carl Th. Dreyer’s film La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928; The Passion of Joan of Arc) are examples of eternally modern, strong, but tragic women created by “sensitive and intelligent men” who are more “openly androgynous than the average man”; they are apparently also more androgynous than the “literature written by women” that “has been more influenced by what ‘man’ (the men) expected of the women than what it actually was they had to say”.

In her play Ditto Datter (1967; Ditto Daughter) she creates a feminist and nightmarish vision of the future, one in which the “International Sterilisation Decree of 2017” is the grand turning point for a new world order, and where the “two-gender era” has been eradicated. The framework around this high-tech female world, which is barren and empty, is a dialogue between mother and daughter who together embark on a journey in records back to historical or fabricated encounters between the sexes: Heloïse and Abélard, Ninon and La Rochefoucauld, Kierkegaard and Clytemnestra. Elsa Gress presents a historical understanding of the gulf between the sexes, and also a critique and caricature of a radical version of feminism. In a sense, the play corresponds to her general critique of what she sees as the trend towards erasing the sexual relationship between the sexes in favour of the ‘insistence’ of a new era (the 1960s) on uni-, bi-, and homosexuality.

Elsa Gress sees Carl Th. Dreyer’s film La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928; The Passion of Joan of Arc) as symbolic of the individual person’s resistance to the system. In Er der nogen der hører efter? (1964; Is Anyone Listening?), she writes: “An individual has refused to give in, refused to be a yes-woman. She is to be burnt alive in an unfeeling, indifferent world, where cruelty is daily fare.”

Her angry attack on the institutions that had no understanding of art, and which fostered mediocrity, gradually developed into harsh attacks against the movements on the left wing, in the women’s movement or the gay movement. Albeit grouped with the cultural radicals, as the female counterpart to Poul Henningsen, her aristocratic outlook on the artist became increasingly inflexible. Her repeated accusations against the popes of culture can, paradoxically, be heard echoed in her own categorising critique of the new movements that took over the cultural arena from the 1960s onwards. As castigator of society, culture, and gender, she certainly made sure the readers were “listening” – but she did not get them to toe her line.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch