In Aase Hansen’s (1893-1981) first published novel, Ebba Berings Studentertid (1929; Ebba Bering’s Student Days), a young woman called Ebba moves from the provinces to Copenhagen in order to study political science. Her expectations of this new life are high having listened to the school graduation speech, which referred to the liberated woman “who really can share with us, because she now has a stake and role in the world around us”. Disappointment is remorseless, however, as the city and male fellow students do not live up to Ebba’s dreams. City life and student life do not make for a meaningful life – she finds but vacuity, jazz, loose sexual morals, and unhappy love affairs with the men who will not, when it comes to it, share the world anyway. In resignation, once all her illusions have been shattered, Ebba allows herself to be seduced by a married man from her childhood town.

The story is not only about the vacuity of the modern day, however, but also about Ebba’s and the narrator’s hesitation in handling its promises. Life in the city is seen in the light of the provincial life left behind and the lost, unequal, but dignified relationship between the sexes. This ambivalent relationship between women and the new era is the constant theme in Aase Hansen’s writing; from loss of innocence – transition from ignorance, provincial life, and youth – to intellectual and sexual experience.

Aase Hansen had studied Danish, English, and German at university, and was thirty-six years old when she published her debut novel with its tale of university life. Slightly older Ellen Raae (1885-1965) had studied Danish and English. They belonged to a generation of women for whom citizenship had been won, but the victory did not feel like a personal triumph. Along with writers such as Johanne Buchardt (1908-1948), Ellen Duurloo (1888-1969), children’s book author Estrid Ott (1900-1967), working-class writer Caja Rude (1884-1949), and Karen Bjerresø (1922-2004), they comprise a group interested in and troubled by the interplay between women’s demands on life and the new age as promise and threat.

There is a group of writers whose fate in the annals of literary history has largely been one of silence. In Dansk Litteraturhistorie (1967; A History of Danish Literature), Torben Brostrøm only mentions Aase Hansen, a woman who has “published a large number of thematically closely-related novels that can be difficult to tell apart.” Her books are “short on plot”. “The intimate and private aspects are accentuated by the weak contemporary flavour; they could actually take place in any period whatsoever.”

City Life and Love Life

Johanne Buchardt was born in a workhouse; her mother was German, she did not know her father and she grew up with a foster family living in the countryside. Between 1939 and 1948 she published six novels, all infused with the same intense longing to be visible, worthy, and acclaimed. Buchardt and her characters want, on one hand, to be recognised as morally superior, bearers of the values of tradition, but on the other hand they also want to be rewarded with solid financial and career success. The city becomes a breeding ground both for soullessness and for fulfilment.

Johanne Buchardt’s lack of personal heritage shows itself in several ways. One tendency in her writing is the feeling of emptiness, lack, and depression, a mood she tries to escape by means of a ‘borrowed’ inheritance. In her first published novel, Født til Graad (1941; Born to Tears), about orphan Lene, her heroine fails in her attempt to get along in the modern urban world. At death’s door, her total suffering is described as that of a Christ figure martyred in order to rise again in the countryside with nature, motherhood, and her husband Sejr (Victory).

The newspaper Berlingske Aften characterised Johanne Buchardt’s first book as being the work of a “dilettante” who borrows from Anton Nielsen, Skjoldborg, and Aakjær (“of course, there is also something of Johanne Buchardt herself, but it is not the best part”), whereas Hakon Slangerup (Nationaltidende, 10 February 1941) was more encouraging:

“Johanne Buchardt’s book has promise – because it is not just a story about herself, but has its greatest value in what it has to say about others. This young writer has a keen eye and a gift for form. She need not stop at the one novel, which everyone can write about themselves.”

In her key work, Der gaar ingen Vej tilbage (1944; No Way Back), the girl Ingeborg overcomes lack of a personal heritage and creates her own identity – seemingly out of nothing – as an independent, visible, and financially successful milliner. She has to distance herself from insupportable maternal images: her mother is one of Johanne Buchardt’s many portraits of wretched biological mothers. On the other hand, Ingeborg’s first employer gave up love in order to pursue her career – in Ingeborg’s symbolic ‘birth year’ 1914. Together, these two mother figures constitute the split itself – between love and career – while a third, her employer in Copenhagen, combines the two aspects in a mannish lesbianism.

“Only at night, when he took her in his arms, did tenderness burst into dizzy passion driving them towards one another in a union that seemed as natural as their own bodies, as lasting as the sound of their own blood and as inevitable as death itself, which some day awaited them. Their feelings for one another were renewed in these hours, reached a height they had never reached before – and which they would never again reach, and which seemed on the brink of devouring them. They did not know, neither of them knew, that a fire like this, which in its blazing savagery ascends to heaven itself, is always a portent of death.”

Johanne Buchardt: Der gaar ingen Vej tilbage (1944; No Way Back).

As was the case in Aase Hansen’s writing, the suspicion here is that women’s dignity and equality are afforded less of a guarantee by the new arrangements for love between man and woman than they were by the traditional marriage patterns. Ingeborg liberates herself from her sexual passion and turns to a man whose scar – symbolic castration – guarantees a lust-less love based on compassion. This solution also turns her into a living paradox: she has to combine the beautiful and deep love affair with the dream of a successful career, as can be read into the elegant dress with which she eclipses her envious mother.

Socialist Moral Standards for Young Women

Caja Rude (1884-1949) presents the Social Democratic movement as a solution to the young working-class woman’s struggle. The lone woman in a long list of Danish working-class writers, she made her publishing debut in 1929 with a collection of short stories, Skyggebilleder (Shadow Figures). The very next year, she embarked on her series of stories for young women, addressing the correct understanding of a working girl’s role in the family, in the workplace, and in relation to the opposite sex. These books should also be read as a response to a basic need: in her most well-known novel, Kammerat Tinka (1938; Comrade Tinka), the central character calls for texts dealing with the lives of workers and young women. Tinka can point to books written by Karin Michaëlis; like these, Caja Rude’s novels constitute an aesthetic universe, where the young working women can see their own lives reflected and interpreted.

The educational aspect is central to her work: in Magasinets Else (1936; Else of the Department Store) the heroine lectures her friends about the danger of being so vain and pleasure-seeking that they might embark on a relationship with a man in order to get clothes and be taken to nightclubs. Pleasure-seeking leads to unwanted pregnancy and social degradation. The working girl had to learn to control herself and to bolster her sense of self-worth by means of knowledge, competence, and work. One of Else’s friends has chosen to go into the bricklayer’s trade; her mother, on the other hand, is a stay-at-home housewife. Caja Rude makes the case that the new generation of young women entering the labour market is a necessary and unproblematic development.

Motherhood is central to Caja Rude’s visions; it provides salvation for man and woman alike from the pitfalls lying in wait for them both: aggressive sexual instinct and anti-social anarchy.

Work also has a function in relation to the men, who are forced to respect their strong wives. Caja Rude’s mother figures evolve throughout her writing career. At first, the mothers are weak and poorly. Later, they are the incarnation of a particular female autonomy, which culminates in the person of Tinka’s mother, who always gets the better of her somewhat old-fashioned husband. Work and self-discipline are Caja Rude’s solution to the gender battle, to establishing a sexual relationship with men, and to an ideal working-class family. Although she depicts the exploitation of girls and women in grim factories, the exploitation she particularly wants them to avoid is that carried out by men. The core of the women’s lives is the family; from first to last, it is their status in this forum that she wants to improve and protect. The well-functioning working-class family is both the objective and the yardstick for the individual’s life and the means by which to shape good and healthy people.

No word of free sexuality and abortion on demand thus flows from Caja Rude’s pen; on the contrary, she writes a number of articles about the destructive influence of the companionate marriage. She sees the ‘open’ relationship as an intoxication of pleasure that permeates every aspect of life, from the erotic to an overconsumption of restaurant dining, alcohol, and taxis; taken to its logical conclusion, it leads to financial and moral ruin. The big problem with companionate marriage is that it is not based on producing children and therefore deprives the woman of motherhood, “and that form of asceticism can drive any normal woman to hysterical distraction”, writes Caja Rude.

In Kravet (1931; The Demand), young Agnes is thrown out into the world when her father turns into an alcoholic; her mother is powerless and ashamed of feeling sexually drawn towards her husband. Agnes is initially a little lamb of God: a sacrificial lamb for her father’s lack of control and her mother’s lack of personal responsibility. The remarkable aspect of the novel is that Caja Rude takes Agnes through a transformation that leads her into the role of spirited heroine about to embark on marriage and enter the workplace. In the first part of the novel, the narrator looks on with a mixture of horror and fascination as the men, intoxicated by alcohol and bestial instincts, oppress and wreak havoc on the women; in so doing, they cause the breakdown of the working-class family.

She shares the idea of the necessity of discipline with other sections of the socialist movement. The workers’ parties also wanted to be able to present their own class as being morally superior. A number of fantasies were, however, also at play: about the nature of men and women and about the possible directions of sexual instincts within the family triangle. In Caja Rude’s writing there is no mediating factor between the image of the humiliated woman with no authority over her personal affairs, but with a body ravaged by the man’s urges, and the fit, spirited, and informed young woman on her way into a marriage defined by equal parts companionship and motherhood.

Battle of the Sexes

Instinct and motherhood are recurring themes in writing at the time – the family as such being the sore point. Ellen Raae’s oeuvre comprises a series of stories about young women who go to the city in order to get an education and provide for themselves; the city, however, proves fatal by being the manifestation of their lack of history and lack of roots: the family they left had not given them the ballast with which to navigate their new life. In the mock ‘home’ that is the boarding house, the landlady is more like a brothel madame handing over the young woman to her seducers. Degrading and rape-like seduction is a recurring theme, and it is accentuated by the seducing man coming from within the house – a father or a brother.

The seduction is thus a twofold battle: between the young woman and the man, and a battle inside the young woman between her abhorrence and her desire, which the man generates through his words, spoken and written, and his action. Ellen Raae interprets the women’s problems in terms of the psychology of drives, inspired by concepts from psychoanalytic theory about splitting, repression, and therapeutic confrontation with childhood. In Frigørelsen (1949; Liberation), her young female lead encounters aspects of herself in a younger woman – who manages to establish a harmonious relationship with a man. Instead of getting a man, the central character gets a ‘room of her own’ – a lovely and well-appointed apartment. In the closing sentences of the book, however, Ellen Raae fuses the two together into one utopian complete woman.

Gæsten (1955; The Guest) puts the battle between man and woman – and within woman – under the microscope. The story is made up of three conversations with and about the same man – called “the guest”. Ellen Raae presents the battle between the sexes as a battle about language. The man and the woman do not simply argue with words, they also try to read the other’s desire behind the word. The man’s reading of the woman’s body and sexuality proves to be the woman’s weakness. The woman’s appetite for the man is a defeat, both for her personally and for female principles and values. Women only find independence and freedom in their own, solitary, room. With regard to this hard-won women’s room, the men are either irresponsibly childish but powerful parasites or, like the husbands in Tidens Tryllespil (1941; The Enchantment of Time), they are patriarchs who make it their business to fit out the rooms for the women.

Ellen Raae shares Johanne Buchardt’s outlook when it comes to understanding women’s desire as a threat against female self-respect. Love is dangerous, balance tricky, and in Ellen Raae’s writing we are far removed from Aase Hansen’s idyll of times past. Women’s very existence is problematic.

“Only the present was real, and the present was Mogens, who murmured little, affectionate words, not promises, never promises, never words of love, merely the sweet, intimate words she knew so well, and which always made her weak, like now. His small tough hands touched her skin – she knew them, too, her skin knew and remembered them, they had once, long ago, touched her, and ever since she had always just longed for them. Now they were here and loosening her clothes, lifting and carrying her, laying her down.

‘Come here, he whispered, – Are you going to come here? Her mouth gave no answer, but her body was answer enough, she no longer resisted. She went to him.’” Ellen Raae: Gæsten (1955; The Guest)

“When Mum was a Boy”

Life is also difficult for the female of the species in the work of children’s book writer Estrid Ott (1900-1967); in her girls’ books she focuses on the physically active, plucky girl who has an unspoiled appetite for life – until the demands made of an adult woman’s life make themselves felt.

Estrid Ott made her literary debut at the age of seventeen; she had been a Girl Guide (cf. Spejderminder (1919; Memories of a Girl Guide), passed the upper secondary school leaving examination, worked as a journalist, and travelled the world. The challenges of life as a Girl Guide, education, and travelling on short or long journeys are the central elements in her stories about and for girls during the inter-war period, and via the many reprints of her work, right up until the late 1960s. Her books for young children in which Bimbi, a soft-toy elephant, describes his lively life with Babsi, a young girl, (1936-1947) can still be found on library shelves today.

Fourteen-year-old Kari, living in the Norwegian mountains during the 1850s, is the epitome of a wild tomboy. She cannot concentrate on her weaving, and would much rather go off with the boys to check up on a bear they have spotted. She suddenly finds herself far too close to this bear, it prepares to attack – and she shoots it. That is how she gets her name, Bjørne–Kari (Bear-Kari), which is also the title of the book, published in 1945. In all her naturalness, and with her strong ‘anti’ streak, she is a leading character in the series of girls who show themselves to be far more interested in a life beyond the calm domestic pursuits of the home.

Behind the picture of the spirited girl there lies, however, a conflict; one most clearly displayed in the early part of Estrid Ott’s writing career. It deals with the young girl’s troubles in choosing between her father’s world, with its freedoms in life, and her mother’s world, a far more onerous woman’s existence. Before she really settled down as a writer of children’s books, Estrid Ott wrote a book in collaboration with her mother, Olga Ott: Vi tre. En Roman i Breve (1923; We Three. A Novel in Letters), a tale for adults about a young trainee journalist, with the symbolic name Vera, who finds herself in a difficult position between her divorced parents. Her aim is to turn from her father and towards her mother, and also to re-establish a family unit, a “we three”, that has been shattered by several generations of strife and acts of revenge.

Vi tre is a deeply serious novel written in an impassioned tone not often heard in Estrid Ott’s girls’ books. Some aspects of this seriousness and of the same conflict are, however, found in Skal – skal ikke (1930; Shall – Shall Not), with the sequel Kære Chester (1931; Dear Chester), where the girl is caught between her father’s plans for her to pursue a ‘male’ career matching his own, and her weak-nerved mother’s dream of seeing her daughter in beautiful ball gowns – i.e. in an eroticised, but also more passive, female role.

Sonja’s nightmare:

“She dreamt that she was wearing a gown with a train. A train so weighty that it was almost impossible to drag across the floor. She suddenly turned into a horse pulling a heavy load. She leant forward in the harness and heaved all she could; but it was not to be moved.

“Then she was standing in a large hall with many mirrors; rooted to the spot, because the train was made of lead.

“She could see her reflection; saw another in the mirror behind her. Chester Gordon, laughing and laughing. Chester Gordon, who had planted himself on her train so she could not budge.”

Estrid Ott: Skal – skal ikke

Estrid Ott’s extensive output of girls’ books is brighter and lighter in tone, but behind the many happy images of girls there lies a deep disquiet about the woman’s life altogether, strangely mixed with an automatic acceptance of family life, by and large always seen as cheery, often unorthodox, and parents generally have very little authoritarian inclination.

Motherhood and Paternal Power

A number of Estrid Ott’s mothers place her in the ranks of those writers for whom motherhood is a problematic area. Aase Hansen, Johanne Buchardt, and Ellen Raae all describe the route to motherhood as being obstructed by deeply ambiguous images of mothers and fathers. The mothers are very occasionally idealised, usually they are dismissed as unfit for use, whereas the fathers are bewildering, seductive, all-powerful, and often scary. Behind the newly-won social rights there are old, unresolved images of the husband, the father, and the mother obstructing the pleasurable conquest of the future. These can be viewed as inner traumas, as ties to paternal authority, but also as images of more extensive conflicts between the sexes.

These are the conflicts that torture the young Karen Bjerresø’s heroine, a dentist called Birgit, and from which the novels about her, Men der kom ingen (1945; But No One Came) and Ene mod mange (1946; One Against Many), attempt – with a lot of effort – to extricate her.

“Now I can picture my mother with, it seems, flaming eyes, and her thin hair – for at the moment she wears neither scarf nor cap – standing up on her head like angry fire-spewing serpents; I again feel a little of my childhood and youthful terror for the holy wrath of Faith. Should I allow the incandescence I feel down inside me to bubble up, then I can make myself mad as a dancing dervish, and then I will see the fire go out in her eyes and give way to a wondering horror, her arms will drop listlessly, and she will entreat me to be the me she knows. I have been through that once and twice in days gone by.”

Aase Hansen: En Kvinde kommer hjem (1937; A Woman Comes Home)

Birgit is well-educated and has her own clinic, but she is caught between the demands put on her by her parents, with whom she still lives, and her body’s unanswered call for sex and pregnancy. In her frustration, she tries to solve all her conflicts at one stroke by deciding to be a single mother: by this means, her body would come into its own, she would be liberated from her parents and her father would get the grandchild he dreams of. This ambiguous project does not succeed, however, as her father rejects her; in Karen Bjerresø’s story, motherhood is thus simultaneously an answer to the woman’s longing, an image of her social suffering, and the core of her –unresolved – showdown with paternal authority.

The moral of this story is even clearer in Ellen Duurloo’s writing. She already had a long list of children’s books to her name when, in 1939, she published her first books for adults: a trilogy, starting with Han skal herske over dig (1939; He Shall Rule over You); the second volume is titled At elske (1940; To Love), and the third part Gud er Kærlighed (1941; God Is Love). The trilogy launched a long and popular list focusing on love and confused desire; for example, male homosexuality in Dømt til Undergang (1945; Doomed to Destruction), and male Don Juanism in Elsket og savnet (1947; Loved and Missed). The theme is treated with fascination and seriousness, but also occasionally for the sake of titillation. The strange machinations of sexual desire can provide spicy entertainment, as in Fru Ellermans pensionat (1949; Mrs Ellerman’s Guesthouse), which is a veritable guided tour of human perversion and callousness. In her debut trilogy, however, she treats her subject matter with absolute seriousness.

The story is one long account of the battle against an authoritarian father and an authoritarian father-image that entirely overshadows the mother and the main character Else’s own maternal role. The father is described as an academic rebel and progressive, and in this light his exercise of authority over his daughter seems even more paradoxical. He sends her to a corrective home for ‘fallen’ young women, run by the evangelical wing of the Danish church, and in so doing hands her over to the female substitute parent, a cruel and asexual, powerful mother figure who obstructs any embrace between father and daughter. After these early years, the rest of the daughter’s life is spent trying to find a father substitute she can both love and live with. Intemperate desire and intemperate anxiety tie her to an ill and sadistic husband, until their daughter symbolically dies – a mark of the destructive nature of their relationship. As in the work of Ellen Raae, desire becomes a self-destructive force that renders the woman an easy victim of the violent man.

Maternal Heritage and the Art of Writing

In Ellen Duurloo’s work, Else’s constant unrest and longing to be controlled and find peace becomes an expression of her thorough sense of alienation.

This dilemma is explored most exhaustively in Aase Hansen’s extensive oeuvre, the backdrop to which is woman’s lack of identity in herself and in her day and age. In Aase Hansen’s interpretation, women can choose to live as ‘loving’, without control of their own desire, or they can choose to be thinking, listening, and writing women who make a living from being distanced. With some degree of sadness, Aase Hansen takes on the latter female role – having, in her early works, raged against the modern, intellectually uneasy woman. For are intellect and pen not the province of the father? Can modern women be in any way seen as a continuity in relation to the mothers’ lives – those mothers who get forgotten, lost, disowned, silenced, and loathed in the women’s narratives?

In En Kvinde kommer hjem (1937; A Woman Comes Home), the narrator moves towards reconciliation by facing up to the mother she has run away from: she goes to visit her in order to try and understand her. The book is an account of a frustrated, unemployed, and single modern woman who returns to stay with her mother for a period while she takes time out from her failures and tries to find a job. The mother is an eccentric, religious, and somewhat irascible woman; in her youth, the daughter had turned her back on her mother in order to go along with her father’s more realistic outlook on the world. Thus, the mother is far from being an ideal role model to which a daughter could sentimentally turn when career and free love disappoint. The moral of the story is that she can nonetheless transmit valuable experience, if the daughter looks at her with different eyes, no longer child’s eyes seeing her as the fierce, often angry, mother body. The daughter has to look through adult eyes and see that her mother is small and cannot cause her anxiety – but that, in all her eccentricity, the mother is in possession of a strength, an integrity in relation to the father’s world, which she passes on to her daughter by supporting her education. Once this new mother-perception has fallen into place, the daughter can be reconciled with herself, with men, and with work, and she goes away – to be called back again, to her mother’s deathbed where the final interpretive breakthrough takes place. She realises that she can turn towards life without guilt, and thereby act according to her mother’s values – despite their dissimilarity; that by living her own life, she will be taking her mother’s side – that her mother had been on the side of life. And mother and daughter return home – each to her own home.

Ene mod mange (1946; One Against Many) was published one year after forty-two-year-old unmarried head teacher Inge Merete Nordentoft had announced that she was pregnant. This news provoked an intense debate in the entire education system and prompted calls for her dismissal, but 1,200 of the school’s 1,900 parents supported her and thought she should keep her job.

In this, Aase Hansen comes close to reconciliation between woman, the past, and the future; the narrator is even reconciled and united with the husband without feeling threatened. In her next novels, the narrative voice and the narrated woman often fall apart – the one has consciousness and pen, the other has the tempestuously lived love life, and often, as in Drømmen om igaar (1937; The Dream of Yesterday), they cannot help one another. The narrating woman becomes the confidante, but is also powerless, one whose own life remains secret and blank, while the woman’s life lived in pursuit of love is far from idyllic. Here, we see women who succumb to the seducers and to their own inner obsessions. In the work of Ellen Raae, the women are split between ill-fated desire and cool solitude, while Ellen Duurloo’s Else founders in the unfulfilled desire without daring to make something of her intellect.

The Fall has, in Aase Hansen’s context, become a part of womanhood itself, and the narrator often only just manages to save herself from succumbing, too. Writing, on one level, becomes an alienation from female destiny – but also a rescue from it. To be “A Woman of Profession” (from Skygger i et Spejl; 1951, Shadows in a Mirror) provides respite and a room in which the narrator can cautiously stand firm, against the times, against the unrest of the woman’s heart, against traumas of the past.

Anne Birgitte Richard

Nationalism, Racism, and Sexism

In her very first novel, Zigøjnerblod (1903; Gypsy Blood), Olga Eggers (1875-1945) was concerned with women’s sexual emancipation – a theme that was to become a key issue in her works of fiction, supplemented by a growing disillusion regarding opportunities open to women in the existing society. Her writing career, which she pursued from 1903 until 1942, covered fiction, journalism – and pro-Nazi campaigning articles. Her fiction culminated and ended with the novel Erotik (1932; Eroticism), which examined the preconditions for love relationships and attacked the restrictive and bourgeois prejudices current at the time.

As far as passions, surprises, imaginative leaps and bounds are concerned, Olga Eggers’s life is on a par with the novels she wrote. Her father was a Baron and Police Lieutenant in one of the Danish colonies, Sankt Thomas (now Saint Thomas, US Virgin Islands), which was where she was born. She was still a child when the family moved back to Denmark. Aged twenty-six she married a writer and sub-editor on the magazine Familie–Journalen, Ludvig Ferdinand Adolf Rosenberg, from whom she was, however, relatively quickly divorced. In 1912 she married again – this time a man who later became professor of philosophy, dr. phil. Anton Ludvig Christian Thomsen. After his death in 1915, she spent the rest of her life alone. A woman from the respectable bourgeoisie who slowly but surely broke with the lifestyle and the conventions to which she had been born.

In Zigøjnerblod she expressed some optimism in relation to women’s sexual liberation; but by the time she published her second novel, Moderne Ægteskab (1904; Modern Marriage), aspiration was already focused on the home that had previously been considered a prison.

It is apparent from the very outset of Olga Eggers’s writing career that she sees men and women as being essentially different. Women are emotionally more stable, and they are also only able to love once in their lives – as we discover unequivocally in the novel Den røde Synd (1908; The Red Sin).

Above all, however, motherhood and maternal feeling is the woman’s specific asset. Maternal feeling is seen as inherent in all women, and it can therefore also be activated in relation to adopted children, as is the case in En Mor (1919; A Mother) and En grim Kvindes Bekendelser (1909; Confessions of an Ugly Woman).

In her novel Erotik, Olga Eggers addresses a number of themes from her early works. These themes are illustrated through three women and their widely differing circumstances: two sisters, both married, one unhappily to an affluent man, the other happily to a poor man with whom she has five children; the third woman is the sisters’ mutual friend – she once experienced a great love, but has now resigned herself to trying to live independently, which gives her the freedom of a self-supporting woman, while she has to forgo security and motherhood.

In the novel, Olga Eggers shows how these three women, each in her way, are deadlocked by circumstances over which they have no control. One of the sisters is unhappy and cooped up in a loveless marriage, which she breaks out of when – for the first time in her life – she falls passionately in love with another man. In Olga Eggers’s fiction, this passion is seen as dark and destructive, and the affair ends when the woman, who has abandoned herself to her passions, is in turn abandoned both by her lover and by her husband.

The other sister lives in a happy relationship with a man who has trouble providing for their four children. She becomes pregnant with child number five, and resorts to a backstreet abortionist; the abortion fails, however, the pregnancy is not terminated but the foetus is damaged and the child is born with a disability.

The ideological message of the book is passed on by a doctor – somewhat surprisingly, this message starts with a warm defence of eugenics and then goes on to advocate dissemination of information about birth control. The doctor is in favour of abortion on social grounds, and he finishes off by talking about the state’s obligations towards mothers.

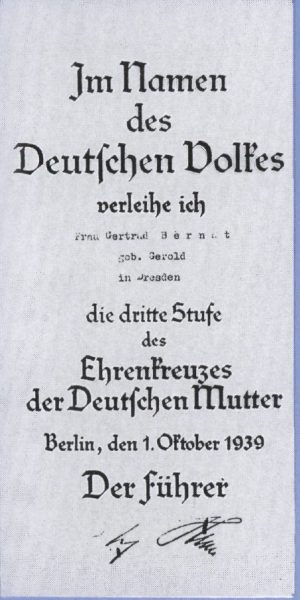

In 1935 Olga Eggers joined one of the Danish Nazi parties, DNSAP, Danmarks Nationalsocialistiske Arbejderparti (National Socialist Workers’ Party of Denmark), and in 1939 she was made editor of the Nazi journal Kamptegnet. The articles she wrote for Kamptegnet propose views on motherhood that fit in with those worked into her novels.

A fundamental factor in the Danish Nazis’ ideology was, like that of their German role model, racism. Nationalism, racism, and sexism are the three buttresses of Nazi ideology, and in this respect Olga Eggers’s views were no exception.

Eugenics, regulation of the human genome, which was taken to its ultimate consequence in Nazi Germany, had already been introduced in Erotik, but the extreme racist views expressed in Olga Eggers’s articles after 1935 are in direct conflict with the, certainly naive, but also open, tolerant and non-discriminatory attitudes expressed in, for example, her travel book Ene Hvid gennem Liberias Urskove (1931; A White Alone in the Liberian Jungle).

A major experience in Olga Eggers’s life was a voyage of discovery she made to Liberia in the late 1920s. She described the journey in Ene Hvid gennem Liberiets Urskove (1931; A White Alone in the Liberian Jungle), in which she argues against racism, against prejudice against black Africans.

One can choose to read these contradictions as a clear rupture in Olga Eggers’ existence. Perhaps, however, they should rather be seen as an expression of a gradual process towards greater and greater mistrust and disillusionment. Olga Eggers lived to see the collapse of Nazism. She was arrested immediately after the Liberation of Denmark in 1945, and died a few days later in Vestre Fængsel prison, sixty-nine years of age.

Annelise Ebbe

Translated by Gaye Kynoch