Is it possible to describe Karen Blixen (1885-1962) as modern? Both as artist and as bearer of the myth that, in the second half of her life, she stage-managed and performed in an indivisible unity of life and works?

In Dansk litteratur 1918–52 (1952; Danish Literature 1918-52), literary scholar Sven Møller Kristensen places Karen Blixen in the early modern literature category along with Nexø, Claussen, Pontoppidan, and Gyrithe Lemche. She “seemed like something isolated and alien, like an element from another world in the critical and social realist literature of 1930s’ Denmark.”

Of Syv fantastiske Fortællinger (Danish 1935; Seven Gothic Tales, 1934) we read that they cannot be summarised, because for that “they are too complex, labyrinthine, refined in composition, […] it is a matter of imaginative art, a game of artistic fantasy that is principally an end in itself.”

At this point in time, Sven Møller Kristensen was on the cultural-radical and critical-socialist wing of Danish cultural life. The communist writer Hans Kirk reviewed Karen Blixen’s books favourably in the newspaper Land og Folk. In a radio review broadcast in 1958, the author Hans Scherfig, also a communist, when speaking about Karen Blixen’s feudal origin characterised her by means of an analogy to the evolutionary story of a living fossil: “Like the rare okapi, the writer Karen Blixen is what natural history calls a relic – a still living descendant of an extinct species.”

To question her modernity is probably not a bad line of approach when characterising her outsider position vis-à-vis a Danish literary tradition, in which the realistic novel is dominant. But the issue of Karen Blixen’s modernity can also lead to a discussion of her position vis-à-vis a large area of twentieth-century Western literature in which women writers are responsible for some of the pinnacles of modern literature and literary modernism. We can simply make a mental comparison with two of Karen Blixen’s contemporaries: the English writer Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) and the Finland-Swedish poet Edith Södergran (1892-1923). Neither of these two leaves any doubt that they have, respectively, expanded the boundaries of the novel and added a new self-assured and ecstatic tone to modernist poetry in Scandinavia. And it is true of both that the artistic development they represent, and the forms they arrive at, are associated with a development and an experience of value as female individual.

Despite her fame being just as widespread as that of Virginia Woolf and Edith Södergran, in the comparison Karen Blixen – with her ‘aristocratic myth’ and with her revival of a long-gone and outmoded storytelling form – seems to be a marginal and brilliant curiosity who can delight the reader, but can also be put aside for long periods.

Karen Blixen’s writing career came late and against a backdrop of heavy personal losses. Being turned from “human being into printed matter” – as the young writer Charlie Despard describes himself in “Den unge Mand med Nelliken” (“The Young Man with the Carnation”), Vintereventyr (1942; Eng. tr. Winter’s Tales) – was not part of the young and younger Karen Blixen’s plan, as we can see in Breve fra Afrika 1914–31 (1978; Eng. tr. Letters from Africa 1914–31). In this correspondence with her family – and particularly with her brother, Thomas Dinesen – where the person Karen Blixen appears more genuine and conflicted than in any other work, her storytelling talent emerges as just one element among others making up a unified, intense process of life and love. Self-realisation is a transaction, and in this approach to life the human being becomes real, and self-realisation is the central value in this inter-war period. It is this unity of life and self that she lost when financial problems forced her to abandon the way of life she had built up on her coffee farm in Kenya, at the same time as the great love of her life, Denys Finch-Hatton, died in a plane crash. If one adheres to the view of overall self-realisation as a unity of the individual and a human community, then the losses are not just something linked to personal biography. In her re-workings, they grow into manifestation of a modern experience of loss of worth, a divided mind, and emptiness.

Although Karen Blixen’s losses were profound and concrete, her realisation of life was also extraordinary and rich. This combination makes for a conflict that in the end results in Karen Blixen – as a writer and depicter of reality – not deploying her talents in the novel of disillusionment; that form of fiction which describes the slow loss of opportunities in an increasingly wearing conflict between the individual and the narrow bounds of society and family.

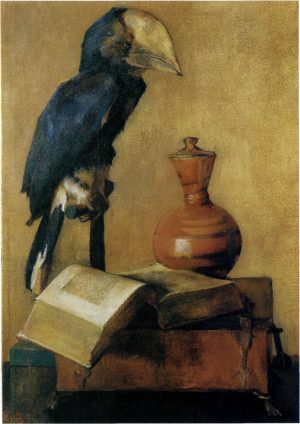

The novel of disillusionment, emerging from nineteenth-century literary naturalism and realism, was a key form for many twentieth-century women writers. Karen Blixen goes behind the tradition of realism and back to a narrative tradition stemming from the Arabian Nights, from Boccaccio, and from Cervantes’s stories in Don Quixote (1605 and 1615). A tradition which she combines with the eighteenth-century philosophical novels that have a narrator who deliberately plays with illusion and story, as we see in, for example, Diderot’s Jacques le fataliste et son maître (1796; Jacques the Fatalist and his Master), and in Johannes Ewald’s Levnet og Meeninger (written 1775, published 1804; Life and Thoughts). Furthermore, and as an essential prerequisite, she finds inspiration in Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy-tales with their compressed accounts of human psychology and transformation.

In his essay “Der Erzähler” (1936; Eng. tr. The Storyteller: Observations on the Works of Nikolai Leskov), the German writer, cultural critic, and philosopher Walter Benjamin points out how archaic, outmoded, the tale seems after the invention of printing. The modern novel, which evolved along with the middle class, is the domain of the solitary individual, whereas the tale is the province of shared experience. The novel encompasses the individual’s fear of death, whereas the narrative voice itself, as expression of a community and a recognising yourself within the community, becomes a transcendence of the death of the individual. That there are fewer and fewer storytellers is also a consequence of a modern devaluation of experience, which started with terrific speed after the First World War, when human experience was contradicted with lies. People were now impoverished, existing in a world that has become alien and unrecognisable to them.

Her tales come in a form that, by seeking inspiration in times before the forms of novel that emerged in connection with the development and crisis of the bourgeoisie, and by means of the narrator’s rhythmic control of the tale, suggests a community that contrasts with the novelistic form’s approach to the individual in his or her solitude. Discussion of Karen Blixen’s form of prose and language often highlights the archaic element; exclusive emphasis on this aspect can easily lead to a foreshortening. The story, as told by the modern storytellers from Cervantes onwards, is a staging and exposure of humankind’s illusions, with the story itself creating a pattern of meaning. This leaves its mark in the story’s perception of life. Alongside the general atmosphere of loss and interruption and distorted human relations, the characters have an incentive in the question of where and how humankind can find hope.

H.C. Branner’s major psychological novel Rytteren (1949; Eng. tr. The Riding Master) was a great success with reviewers and readers alike, and was a much discussed topic – also by Karen Blixen. She wrote a critical essay about the novel in which she accuses its central character, the ‘saviour’ figure Clemens Weber, of being in fact a dishonourable person who carries out salvation automatically – without demanding any effort or action on the part of the one to be saved. Her essay was read by the literary inner circle and was first published in the journal Bazar in 1958. At the end of the essay, where she calls upon the Danish poets to serve up myth and adventure as sources of inspiration rather than writing depictions of reality, she also provides a provocative and paradoxical characterisation of the basic elements in her own narrative form:

“Danish poets of the year of Our Lord 1949! Press the grape of myth or adventure into the empty goblet of the thirsting people! Do not give them bread when they ask for stones – a rune stone or the old black stone from the Kaaba; don’t give them a fish, or five small fish, or anything in the sign of the fish, when they ask for a serpent.”

Reading Karen Blixen’s oeuvre in reverse chronological order, we find a clear answer to this question in her last works. The answer is seemingly modern by trusting in the ability of art to create a meaning that is not found elsewhere. In Sidste Fortællinger (1957; Last Tales), the answer in “Kardinalens første Historie” (“The Cardinal’s First Tale”) is that it is the “historie” of the title (Danish=history/story – here, the tale) that can give the answers to our most burning questions about who we are and what the meaning of our lives is. In the Cardinal’s explanatory comments, the tale, with its revolutionary events and its clear-cut and in a way superficial characterisations – each person having a well-defined role to play within a complex pattern – is faced with a new form of narrative art. His words outline a plain description of the naturalistic and psychological novel:

“‘But I see, Madame,’ he went on, ‘I see, today, a new art of narration, a novel literature and category of belles-lettres, dawning upon the world. It is, indeed, already with us, and it has gained great favour amongst the readers of our time. And this new art and literature – for the sake of the individual characters in the story, and in order to keep close to them and not be afraid – will be ready to sacrifice the story itself.’”

Unlike the novel’s closeness to daily life and recognisable characters, the tale, with its condensed and often enigmatic form, which makes no great efforts to expose the human soul, is an expression of divine or chance intervention in and shaping of human lives so they rise above everyday tedium and mediocrity. For the Cardinal – and for Karen Blixen – the distinctive and crucial aspect of the tale is that here the heroic, the desire to act and be brilliant, exists as value and as an ideal that sets people in motion. There is a hero who sticks to the given project with loyal submission. The tragic aspect, in the form of a choice that cannot be undone, exists in a space and in a time where there are no insurance schemes that can make good the damage and the extreme downturns to which the individual is subjected.

Like the hero, the heroine, too, exists both for the Cardinal and for Karen Blixen. The heroine’s first task is to have an extremely clear-cut exterior, usually in possession of overwhelming beauty and gracefulness. Karen Blixen is not quite exempt from an element in the work of many women novelists and storytellers: that the heroine is a plane of projection for women’s dreams of omnipotence in the possession of overwhelming beauty. The description of Benedetta’s, the Cardinal’s mother’s, beauty must nevertheless be understood as a metaphor for an aesthetic morality in the story’s universe. After the birth of her son, and as a result of her intense love for him, her beauty blossoms with enormous force:

“But your sex possesses sources and resources of its own; it changes its blood at celestial order, and to a fair woman her beauty will be the one unfailing and indisputable reality. A very lovely woman, such as yourself, may indeed feel freest and most secure upon an edge or a pinpoint in life, with this reality as her balancing pole.”

The concentration that enables the balancing act between celestiality and fall is the criterion to be hero. Karen Blixen saw the creation of this concentration and balancing ability – to make it visible as a field of tension, to show humankind’s place between these two poles – as the job of the storyteller and the writer and as the utopian goal of the story.

The Cardinal himself is a dual being in a balancing act between the Dionysiac and the lofty divine forces, so he is servant and creator of humankind rolled into one. He tells his story to a lady and she, despite her respect for his explanation as to the nature of a story, remarks that to her it also seems a hard and cruel game with human beings. And cruel it can be, as in “Kardinalens tredje Historie” (“The Cardinal’s Third Tale”). In this story, the “giantess” Lady Flora not only finds her identity as woman and her participation in a fellowship of humanity, but by the game of chance she also contracts syphilis. The sore on her lip is a symbol that she has, in the sense of the story, come into existence as a tragic-heroic figure.

A tendency to megalomania can be spotted in the role Blixen here ascribes to the storyteller. In a godless world, the storyteller alone has the power to intervene creatively in existence and shape it according to his or her aesthetic and heroic principles. If the story is meaningful, meaninglessness nevertheless also becomes a theme in Blixen’s work. This also comes to light as a theme relating to the artist, which after Winter’s Tales in particular becomes a dominant independent theme in her late writings. Alongside the powerfulness of art, the meaninglessness appears – as in “Storme” (“Tempests”, Anecdotes of Destiny) – as a balancing act in a vacuum. The young actress who plays the airy spirit Ariel in Shakespeare’s The Tempest and who, with the lightness and dauntlessness she takes from the role, intervenes and rescues a ship in distress, also experiences her courage as faithlessness to the world of humans. She belongs elsewhere, and that makes her unable to identify with the lives of others and form real attachments with them. And for this reason, towards the end of Karen Blixen’s writings, story and art alone are capable of being the balancing act between vacuum and substance, between loss and the utopia of a different type of people. The story forms a radiant sphere of light and chill in a fusion of dream and reality.

In Premier manifeste du surréalisme (1924; First Surrealist Manifesto), the French writer and chief ideologist of the Surrealist movement, André Breton, writing in connection with his emphasis on the significance of dream for the creation of a new reality, highlights the fantastical and gothic tale at the expense of the realistic novel:

“In the realm of literature, only the marvelous is capable of fecundating works which belong to an inferior category such as the novel, and generally speaking, anything that involves storytelling […] But the faculties do not change radically. Fear, the attraction of the unusual, chance, the taste for things extravagant are all devices which we can always call upon without fear of deception. There are fairy tales to be written for adults, fairy tales still almost blue.”

Premier manifeste du surréalisme (1924; First Surrealist Manifesto)

The utopia of humankind also includes women; Karen Blixen’s second, simultaneously old and new, picture of the human race has female features, as shown by the Cardinal’s personal background. One of the mysteries of Karen Blixen’s writing is her perception of femininity, even though it is not hard to find her own suggestions on the matter: in her famous and infamous “En Baaltale med 14 Aars Forsinkelse” (1953; “Oration at a Bonfire, Fourteen Years Late”), for example, or comments about and reflections on femininity made by many different characters in her tales. In an early story, “Karneval” (“Carnival”), written in the mid-1920s, the philosophising elderly painter was already pointing out that the new lack of difference between the sexes played a part in the lack of direction in modern life.

In the essay “Moderne ægteskab og andre betragtninger” (written 1923-24, published 1977; Eng. tr. On Modern Marriage and Other Observations), she seems to look positively on this lack of difference. This essay, about the development in marriage and the relationship between the sexes, is written with ’scientific’ detachment and humour, and it proposes a critique of ideology. The conclusion she reached from her investigation of the development in the objective conditions is that with the potential and actual dissolubility of marriage in the modern era, and with women’s self-determination as regards pregnancy, then behind the theatrical rituals involved in the institution of marriage it is actually free love that is being practiced. Following the disclosure of this truth, women especially must change their attitude and take possession of the freedom and love that is right there in front of them. They must acquire the capacity for love and the ideal of love that is found in embryonic form in the story. Love is “play”, released from outer restraint and inner guilt. Nevertheless, this form of love also has its laws and makes its demands of people, which she formulates in positive terms – designating grace and generosity as central values and requirements.

But, as soon as she has found its forms, then a flaw appears in this radiant world of modernity with its lightness. She has no difficulty in giving a satirical account of the bourgeois marriage as it was conceived and developed in the nineteenth century, with its concentration on the narrow family circle and with domesticity as a form of imprisonment and spiritual cannibalism vis-à-vis the individual. The form of marriage she describes with greatest empathy in “Modern Marriage” is the feudal form, in which the individual and the marriage exist for the sake of the family line. The life of the individual acquires transcendence and becomes part of the history of humankind by entering into the overriding organism of the family. It is this transcendence – the result of being tied to history via the family – which Blixen feels to be lacking in modern times.

In the essay “Moderne ægteskab og andre betragtninger” (1923-24; Eng. tr. On Modern Marriage and Other Observations), which gives an account of women’s leap from Victorianism to modern life, Karen Blixen draws up her ideal of modern love. Once the love relationship is released from all the ties of necessity and gender roles, it can assume the nature of “play”:

“Much is demanded of those who are to be really proficient at play. Courage and imagination, humor and intelligence, but in particular that blend of unselfishness, generosity, self-control and courtesy that is called gentilezza. Alas, there has been so little demand and exercise of this in love affairs. […] And yet it is play’s own spirit, true gentilezza, that there is most need of in human love affairs, and that has most power, the minute it appears, to idealize them – whether they are to last for a day or for all eternity.”

In “Modern Marriage” a division appears indirectly in the female consciousness, which cannot see a fulcrum in either the isolated love relationship or in realisation of personal individuality. This division manifests itself as a longing to be part of a greater and living totality. “Modern Marriage”, Letters from Africa, and her early short story “Carnival”, which has its own interesting, contemporary, and desperate tone in relation to the modern weightlessness, ask the question: can a woman who attempts to join together these divisions and conflicting needs exist and be recognised for what she is by others? “Drømmerne” (“The Dreamers”, Seven Gothic Tales) is a sort of answer in short-story form to this question, while also being the connecting link between the young and the mature and late Karen Blixen, and there can be little doubt that the answer given by the story is largely a tragic ‘no’.

Before closer discussion of the masquerade motif in “The Dreamers”, it is worth looking at the lost coherence: she had found it as living and lived reality, and in her fictionalised account of her farm in Africa, Den afrikanske Farm (1937; Out of Africa), it can be seen as luminous and authentic reality and revealed utopia.

In her young days, Karen Blixen also wrote poems. One of the best of these was “Ex Africa”, which she wrote in 1915 while hospitalised in Denmark. It was published in the journal Tilskueren in 1925, like many of her early texts under the pseudonym “Osceola”. The poem addresses many of the motifs and factors in Africa that make it her new found land:

Above the ever-watchful white streetlamps

the moon glides forth tonight between clouds and mists.

Long do I gaze upon you, moon, to see you again

as I saw you before, in the nights

gone by.

To find out if tonight you see

the shadows of clouds scudding across Bardamat,

where the long slope follows the plain.

Can you see your reflection in the flowing Guaso Nyeri?

Behind Kijabe and Kedong,

above Suswa and Ngong,

in my free land, my open land, my heart’s land.

Above the empty expanse of the steppe

shines the Southern Cross.

On the wide and airy plains, in the Masai Reserve.

Sweet was the scent of grass when I came home from hunting.

The smoke rose from my campfire into the pale evening air.

Ismail told stories while he put the game on the spit,

tales of hunting and love from times past.

Sabagathi was all a-sweat while he dragged in the firewood,

Farah carried off my gun and brought out the wine.

Long sparks shot aloft in the cool, clear blueness,

many things rise and pass away in the glow of the fire.

And when I turned my gaze upwards to the dark

night sky, I saw you, glittering solitary and silent

moon on high,

who, while striding onward through your watch,

looks down upon the lions as they hunt.

On the gentle evening plains in the Masai Reserve.

Her acquaintance with Africa is described as a movement from being inside, inside a house, inside an over-civilised culture that has lost its meaning and its challenges, to coming out into an abundant and intense nature and to an encounter with a culture in which the contrast between nature and culture – exactly like that between God and the Devil – does not exist. In Blixen’s words, “the Natives neither confounded the persons nor divided the substance”. For her, the encounter with this culture is a matter of rediscovering something that had been dreamt and sensed, and which is now rendered in a distinct form – just like the ability to tell and listen to stories is an important part of the culture: the Somali women, for example, tell stories in the style of the Arabian Nights.

In this reality, people become more than themselves, because their actions can become material for stories which are themselves reproduced and linked up with a network of stories that might be more than a thousand years old. Thus, everything a woman encounters can become a sign that is her reflection and extension. This is the significance of her encounter with the animals, with bushbuck Lulu’s queenly disposition and with the vigorous and fearless lions. It is in this richness of meaning, made of signs and myths, that Blixen’s concept of destiny – the notion of loving one’s destiny, creating destiny from the seemingly chance circumstance – comes about in contrast with utilitarianism, cautious calculation, and hypocritical piety.

There is one central human relationship in this system of values: that of master and servant. Qualitatively, this relationship is unlike those based on a business exchange or a passing sexual liaison. This relationship becomes the picture of the human relationship that makes the individual more than his/herself. In Skygger paa Græsset (1960; Shadows on the Grass), Blixen’s later reflections on her years in Africa, she compares the relationship between herself and her servant Farah with the relationship between Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Despite the striking superior/subordinate ratio, Karen Blixen sees the relationship as that of equals. In order to discharge duties and fantastic exploits, the master is just as dependent on the servant as the servant is on the master. As in Diderot’s Jacques le Fataliste et son maître, the servant is necessary for the master so that he can attain reality.

Karen Blixen gives an account of the sense of honour and generosity in the master and servant relationship in her African reminiscences Skygger paa Græsset (1960; Shadows on the Grass), when writing about her Somali servant, Farah. Her financial situation proves beyond hope, she knows that she cannot keep the farm, and Farah appears in hitherto unknown splendour:

“And now it happened that he unlocked and opened chests of which till then I had not known, and displayed a truly royal splendour. He brought out silk robes, gold-embroidered waistcoats, and turbans in glowing and burning reds and blues, or all white – which is a rare thing to see and must be the real gala head-dress of the Somali – heavy gold rings and knives in silver- and ivory-mounted sheaths, with a riding whip of giraffe hide inlaid with gold, and in these things he looked like the Caliph Harun-al-Rashid’s own bodyguard. He followed me, very erect, at a distance of five feet, where I walked, in my old slacks and patched shoes, up and down Nairobi streets. There he and I became a true Unity, as picturesque, I believe, as that of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.”

In “De standhaftige Slaveejere” (“The Invincible Slave-Owners”, Winter’s Tales), Karen Blixen describes this relationship more explicitly in a terrible game between two impoverished young women and a rich young man. He disguises himself and acts the role of their family servant in order to reveal and make plain their secret, and in this guise he gets closer to them than he had as wooer. In a flash, the young man experiences a gravitas and direction in his life. Like the master/servant relationship as described in the African context, that which links master and servant is expectation. It is the confidence that both will display great human qualities that takes the relationship to the level of the heroic and the tragic.

As a point of balance between lightness and heaviness, the African world is also a dying world – revealing itself in a glimpse and surrendering its vision as in flights above the mountains – until subjected to efficient capitalist exploitation and racism.

With its heroic values, it is an anachronistic vision. In relation to a twentieth-century Danish readership, which is marked by the labour movement and an endeavour to expand democracy and welfare, this vision might seem to have grotesque consequences: as in, for example, “Sorg-Agre” (“Sorrow-Acre”, Winter’s Tales), where the feudal relationship between a poor widow and a landowner, despite the complete powerlessness of the one, illustrates the will to tragedy.

This anachronistic quality can also clarify the split in Karen Blixen’s perception of post-youth femininity. Her perspective constantly alternates between a female desire for freedom and an attachment to forms and institutions, which is a condition of and facilitates a powerful female self-expression.

In the African world, Karen Blixen – a modern woman with short hair and a car – is enchanted by the indigenous culture’s sense for femininity as value. This appreciation is rendered visible through the acknowledgement of beauty as one of the most important values in society – by, for example, fostering an ambiguous and graceful virginity, which in the course of time is turned into the old women’s dauntless power. There are contrasts between the modern ideal of equality and the experience of femininity as value, as magic power. At the same time, the magic femininity is tightly determined by the erotic self-expression. In Karen Blixen’s work, the erotic self-expression seems to be a source of this femininity, an eye of the needle that has to be got through so that it can change into new forms and manifest its hidden cultural power. This transformation has taken place in the happy, young mother figures, most often mothers to beautiful boys, probably some of Blixen’s most integrated female characters – such as Ulrikke in “En Herregaardshistorie” (“A Country Tale”, Last Tales), who pleads the cause of generosity, or Rosina in “Vejene omkring Pisa” (“The Roads Round Pisa”, Seven Gothic Tales).

The frame narrative in “The Dreamers” – with three men, of whom the one is the Eastern storyteller Mira Jama, on board a boat in the Indian Ocean – is like an ornamented mount in which is set the destiny of the singer Pellegrina Leonis. The patterns and figures are gradually laid bare as the fragments told by the narrators become intertwined. Albeit the form, the time, and space might seem exotic, “The Dreamers” can nevertheless also be read as a story about how extensive knowledge and generous femininity are neither visible nor a recognisable power in the modern world. To Karen Blixen’s female characters, it seems as if this manifold unity and richness of possibility is at risk of being destroyed in the erotic encounter itself, causing a split in the individual woman’s identity, and this is where these women approach tragedy.

In relation to Pellegrina Leoni, this observation is articulated by her friend and servant, the wealthy Jew. Having described her beauty, he gives an account of her meeting with her lovers: “[…] she was like a lady who has put on her richest attire to meet the prince at a great ball, only to find that what she has been invited to is a homely gathering in honour of the police magistrate, at which everyday clothes are worn.” It is also in this context that Pellegrina is characterised as a Donna Quixotta, one for whom life is too little – or the men are too small. They possess neither receptiveness nor expectation in relation to the gift that is woman; and the tragedy is that when a gift cannot find a recipient, then it will become something almost non-existent.

It is not until an accident causes Pellegrina to lose her voice, which is the expression of her special and divine person, and she takes on many personas as prostitute, revolutionary milliner, and nun, that she is able to process the erotic in a masquerade without disappointments, but also without real pleasure. She is a dream-like and fleeting figure – a thought in men’s dreams come to life – who lets others and herself live in a giddy weightlessness. Only at the moment of death, her faithful servant at her side, does she again become whole, and the glow of passion once again washes over her in this meeting with the old Jew, and in the memory of her vocal power.”

Pellegrina’s femininity – both the authentic and the one existing in the fugitive and role-playing woman – is coloured by staging and masquerade. The authentic and also the soulless and resigned femininity must resort to the masquerade in order to survive and be visible; the female aspect cannot be separated from the masquerade or the staging of itself as image. And thus, narcissism, generosity, and revengefulness are mingled in her character. The Quixotic aspect is the disparity between the immense vitality and exertion with which she takes on the world, and the weak and ridiculous response she gets from the world in the shape of constraints and urge for possession. Only in the story – with its complex composition and its meandering pattern, which highlights the moments and ruptures where chance acquires weight and becomes destiny – does she get a real answer as to who she is. The tale renders her visible given that reality, as in the African context, becomes a pattern of signs. The story – to enter into and create such a pattern of meaning and abundance – thus becomes a true answer to what femininity is in the work of Karen Blixen.

With its call for magic heroism and dauntless cheerfulness, this answer is far from the more earthbound notions of equality espoused by a women’s movement that had been in the field for more than one hundred years, and it is also far from the endeavours of a welfare society to procure safety.

In Karen Blixen’s later works, it is an answer that can also have a touch of kitsch about it: her later tales have an in-built high-flown awe at the depth and mystery of the unique artist’s outsider position.

Karen Blixen is nonetheless not a glittering curiosity who as such exercises an augmenting power of fascination in relation to a Western world and a film audience hungry for myth. With her romantic anti-capitalism and with her revival of old narrative forms, which embrace the mysterious and which must render visible another reality – more intense and meaningful – behind the apparent reality, she is in the truest sense a writer who belongs to the twentieth century. With her search for divine powers in the human being, with her disrespectful inversion of what is high and what is low, and with her trust in dream, there is no little parallelism between Karen Blixen’s project and that of surrealism. This is apparent not least in a recognition of the cognitive abundance of dreams – a view central to Karen Blixen’s heroic and new picture of humankind.

Aage Henriksen is the Danish literary scholar to have most thoroughly and perceptively studied the motifs, psychology, and form in Karen Blixen’s stories: in his books Det guddommelige barn og andre Essays om Karen Blixen (1965; The Divine Child and Other Essays on Karen Blixen) and De ubændige (1984; The Indomitable), he goes along with the view of her as a fully-formed genius: from the time of her homecoming in 1931 to her death in 1962, she had “already achieved her final form”. She is modern, in Aage Henriksen’s opinion, by cutting across norms seeking the “realm of the natural human being”, what she calls Lucifer in her letters and God in her stories:

“Now, while this passion for the ideal drove many other excellent souls – for example, Rimbaud, Nietzsche, Rilke – into attitudes of unceasing Excelsior high above ordinary existence, wreaking havoc first on their psyches and then on their minds and health, it moved Karen Blixen along a curve that by a strange parabola brought her back down to the surface of the earth. Fired by the negative force of rebellion, she nevertheless knew how to set limits, to exercise moderation. She never lost sight of the fact that other people, the world around her, reality, were all the solitary rebel’s counterplayers and judges, and that together they would be the ones who, in the last analysis, would decide the worth of all her efforts.”

De ubændige (1984; The Indomitable)

This kind of vision and signs that humans are more than, and can go beyond, the dominance of things political and financial in Western culture is inherent in Karen Blixen’s description of the Kikuyu’s make-up and dancing in a passage from Out of Africa. The description echoes twentieth-century modern visual art and its rediscovery of the condensed stylisation and magic expressive power of primitive masks and sculptures; Blixen’s description of the young Kikuyus is an image of longing for a multifarious and comprehensive human community, in which art does not imitate reality, but is talent and necessity: “The Kikuyu, when going to a Ngoma, rub themselves all over with a particular kind of pale red chalk, which is much in demand and is bought and sold; it gives them a strangely blond look. The colour is neither of the animal nor the vegetable world, in it the young people themselves look fossilized, like statues cut in rock. The girls in their demure, bead-embroidered, tanned leather garments cover these, as well as themselves, with the earth, and look all one with them, – clothed statues in which the folds and draperies are daintily carried out by a skilled artist.”

Translated by Gaye Kynoch