In 1827, on the Feast of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin, twenty-six-year-old future author Fredrika Bremer was listening to a sermon preached by the famous theologian Bishop J. O. Wallin, in which he interpreted the story of the angel appearing to Mary as described in The Gospel According to Luke.

What Fredrika Bremer heard made her angry, so angry that she immediately wrote not one, but two responses to Wallin, of which she sent the first anonymously. The Gospel story about the angel and Mary is the occasion of much and varied Christian reflection, as indeed Wallin’s assorted sermons on the subject of the Feast of the Annunciation testify, but on this specific Lady Day the theme Wallin chose for his sermon was: “Woman’s noble and serene calling”. He used the story about Mary – when she says to the angel, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word” – to talk about the relationship between men and women.

Wallin’s central point was that the woman must take responsibility not only for her own faith and Christian conduct, but also for that of her husband. The domestic sphere was and remained the domain of the woman, and here there was no excuse for doubt, abandonment of faith, or immodest ways. For the man, on the other hand, his life outside the home could easily cause him to forget God, to doubt or lose his faith, and an unholy life such as this could be, if not excused, then explained by the circumstance that he had not had a devout mother, or did not live with a pious wife who could turn his gaze to God.

“A woman without faith is a disturbing discord in creation; in her I seem to see a living blasphemy of God’s holy name, that which is yet inscribed so deeply in her heart. Should the man not always perceive the divine truths with equal ardour or occasionally seem to doubt them, or perhaps think less thereof and live less therein, he will yet – provided that his words or actions do not manifestly brand him as blasphemer or as godless – in most cases be found but pitiable,” declares Wallin in his sermon.

The eloquent Bishop’s entire argumentation offended Fredrika Bremer, and she deftly constructed her first missive to Wallin as a sophisticated rhetorical retort. She starts off by commending Wallin for his eloquence, asks him gently if perhaps he might soon provide a description of “the man in his domestic setting and the way in which he should behave there” – he has earlier, after all, published his “Religionstal till Qvinnan allena” (Religious Address Exclusively to Woman), and she had hoped that his sermon on the Feast of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin might present just such a description, so that his Christian injunctions should not apply solely to women.

But his sermon had been a sore disappointment to her. Not only could men find an excuse for “their coldness and cool-headedness as regards religion, but also an excuse for the despotic disposition of many” in relation to their wives: “Should one be so fortunate soon to hear a public religious address to the man, corresponding to that to the woman, then there is nothing left to do but simply pray fervently to God that He through it will awaken the conscience of all those who destroy domestic peace” is the sharp conclusion in Bremer’s first response, with an elegant intimation that Wallin’s approach has been anything but Christian and edifying.

Fredrika Bremer’s second response to Wallin is longer and less tactical, and has a less subtly polemic design. She gives vent to her feelings and her annoyance with Wallin:

“[…] profound thinker, great orator, you Wallin – what has thus clouded your clear vision, your sense of truth and fairness, that onto the already adequately full scale pan of the oppressed you place the authoritative words of your disposition and accordingly give divine sanction to the tyranny of cruel prejudice that has long caused and continues to cause the one half of humankind suffering!”

“You demand ‘heaven on earth’ of women and want them to endure the pain, the oppression, and the suffering of which hell itself would approve. You unjustly forgive the offences committed by your own sex while condemning the misdemeanours of the other without forbearance,” writes Bremer in her second response to Wallin.

Bremer energetically submits her counter-arguments, develops her ideas on the mutual rights and duties of a married couple, and ends by addressing her unmarried sisters, appealing to them to serve all people with dignity and self-esteem: “Preserve, through your goodness, the sense of your worth.” It is fascinating to see how, towards the end of her response, Bremer arrives at what she considered to be Wallin’s greatest mistake: “Mary’s relationship to the Saviour, people’s to the deity, can never be a benchmark, an example, for people’s [relationship] to people, for the woman’s to the man.”

Young Fredrika Bremer’s argument was definitely not lacking in theological substance; Søren Kierkegaard, a score or so years later, would presumably have endorsed her line of thought. But he did not give himself the chance to do so. He declined her invitation to meet when she was staying in Copenhagen in the late 1840s.

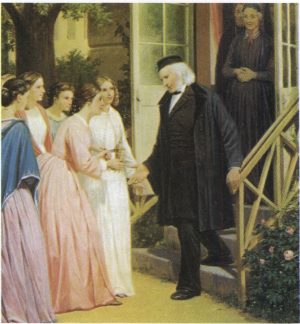

Fredrika Bremer visited Denmark in 1848 to 1849. She associated with Hans Christian Andersen, discussed theological matters with Professor Hans Lassen Martensen (1808-1884) – who later became Bishop of Zealand – and was also keen to meet Søren Kierkegaard. She sent him a letter in which she as “a recluse like yourself” asked Victor Eremita if they could discuss the stages of life. She emphasised that it was the distinguished men of Denmark that made her so rash as to suggest a meeting. He replied, after yet another enquiry from her pen, that he was rash enough to refuse her invitation. In “Lif i Norden” (1849; Life in the Nordic Countries), Bremer gives a less than flattering account of Kierkegaard as being morbidly irritable and temperamental. This caused him to remark in his diary:

“She was good enough to send me a highly genial note in which she invited me to join her for a discussion. Now I almost regret that I did not reply, as I had first intended: no, many thanks, I do not dance.”

Her polemic against Wallin was not Fredrika Bremer’s only analytical venture. She later devoted herself to a comprehensive and carefully argued critique of the German philosopher David Friedrich Strauss’s view of the Bible and his interpretation of the Christ figure. In her text Morgon–Väckter (1842; Morning Hours), she took vehement exception to making historical and critical Bible studies a basis from which to reject the idea of the divine nature of the historical person Jesus. Here again, Bremer was involving herself in a highly topical theological debate, one which was to prove particularly significant in the works of Grundtvig and Kierkegaard, and later in those of Georg Brandes. Throughout her life, Bremer returns time and again to her theological reflections and stresses that her writings stem from religious crisis and insight. In an 1840 letter to the writer Emilie Flygare-Carlén, she explains that she sees herself as “a humble tool in His [God’s] hand for lessening evil and increasing good on Earth”. The imagery of the father’s hand is characteristic and interesting inasmuch as the father’s hand also features in her universe as an icon for the oppression of women in the patriarchal home: “My entire youth passed under the rule of a male iron fist – I cannot tell you with what pride and bitterness I then felt all reductions in the worthiness and freedom of womankind”, she writes in a letter of 1837. Bremer’s relationship with God is very much a case of instituting an ideal father figure, as in Morgon–Väckter where she refers to humankind’s search for God and explains: “This is also known as: humankind’s memories of Paradise, the memories of the House of the Father”. Years before, in the poem “Min Morgonsång” (1828; My Morning Song), she had already depicted her youthful religious crisis and longing for God, longing for “the air of home, to where I shall be borne” and where “the saved children of pain in their multitudes / shall be clasped in the arms of peace”.

Bremer’s perception of God involved a concept of liberation, elevation, and human worthiness. In relation to God, the woman can achieve worth – faith is not self-denial, but inner enlightenment, indeed, a luminous insight – and it is obvious that this concept of worth powerfully and inevitably combines with protest and resistance to the unworthy life offered to women in God’s earthly realm.

In an essay written in 1873, “Fra et mindre hjemligt Standpunkt” (From a Less Domestic Point of View), Norwegian Camilla Collett recalls Fredrika Bremer’s polemic against Wallin and autobiographical accounts of her childhood and youth. Even though Collett distances herself from what she calls the pious veil of mist that descended upon the latter years of Bremer’s life, she misses Bremer’s “warm, sincere soul” and her “testimony” in the modern gender debate. In Collett’s view, the perceptions of the relationship between man and woman against which Bremer so energetically argued in 1827 still hold true and leave their chilling mark all the way through society. Romantic theology’s elevation of woman to divine door-opener, which Collett sees recurring in, among other works, Adolphe Monod’s La Femme (1848; Eng. tr. Woman: Her Mission and Her Life), is to her mind absurd and Catholic: “But now it is again being preached elsewhere, quite openly, that only man exists for the sake of God, but woman for [the sake of] man. Man, who strictly speaking need not lead a life in God, nonetheless exists for the sake of God, while woman, on whom religiosity, that is, God-consciousness and submission, has been imposed as an obligation, only exists for the creature that can do without it! Make this tally, whoever can! For surely the intention cannot be that she exclusively for his sake ought to make sure that she is on good terms with the Deity, as in being a sort of divine door-opener, with the help of whom he, when short of personal recommendation, would undoubtedly be let in? If this is not quite Catholic, then one could nonetheless easily become a little ‘Catholic in the head’ [that is, confused and crazy] over it.”

The elevation of woman is a degradation, and Camilla Collett gives this thinking a rejoinder by means of highly mobile argumentation and approach; she looks out, in, and down, down to the poorest of women: “[…] we must proceed consistently. We must descend the whole ladder, most venerable sirs […] Be my guest, deeper and deeper.” At the end of her essay, Collett turns her attention to “the restless wild pursuit outwards, in which man of our day seeks to escape his inner bankruptcy and to deaden the whole confounded state of impunity and abandon!” The elevation of woman had worn down “Life’s Force of Resistance” itself:

“[…] for he himself has broken it, broken it in the only creation that was worthy of comparison with him, – a force which does not comprise, although it has been the endeavour for so many thousands of years to reduce it thus, lethargy of willpower to bear and tolerate the bad in him and for him, but in inciting to the good.” As a countermeasure to elevation, Collett and Bremer posit the idea of an instructive and stimulating force. In order to be able to express themselves on the ideal of womanhood and the reality, both women had to undergo a language overhaul and demolition of the elevated ideal of womanhood promoted by Wallin and Romantic theology. Female worthiness becomes a central issue for them both, and for many female writers of the day. Their myth of worthiness is a response to the thoughts and ideas on elevation and innocence into which a Romantic mindset often enrolled women and based on which it accounted for them. Worthiness does not put woman in a specific social or sexual situation. The worthiness myth does not give a clear definition of female significance vis-à-vis the male sex, but vis-à-vis a life in the community, a social context where assignments and significance can be formulated for the woman, be she married or unmarried, young, grown-up, or old.

In Camilla Collett’s “Nogle Strikketøisbetragtninger” (Reflections of a Knitter), which she wrote in 1842 but then reworked several times, she complains that men, “our rulers, in their dominion demonstrate so little worthiness, so little maturity”; she describes a scene at a ball, male eyes contemplating the young women:

“Among our young Fashionables there is but one expression that is comprehensible, and that is: ‘She’s damned pretty’. Grace, decorum, intellect, humour receive no consideration, are never sought or in the remotest way appreciated should any such happen to be detected. This manner of observation is disquieting; and yet so it is; like other alert onlookers, the so-called chaperones at the festive gatherings could support the case with their testimony – provided they have no beautiful daughters […] for the balls are indeed the only stage on which the unfortunate ladies have any import, where they can win some garlands with which to adorn their youth.”

The qualities, the worthiness, which Collett wanted the men to see, echo the old eighteenth-century code of virtue applied to reason, personal judgement, and sense of justice; the myth of worthiness is akin to notions of virtue addressed by writers such as Danish Charlotta Dorothea Biehl and Swedish Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht. The myth of worthiness is, however, greatly coloured by its very function as a rejoinder to the sexualisation of woman implied by the ideal of innocence and elevation. It is a female Romantic response to the gender polarisation of male Romanticism.

During what is known in Scandinavia as the Modern Breakthrough, the idea of worthiness was very nearly hidden away behind a naturalistic perception of the body. Worthiness manifested itself as a loss, which was associated with death scenarios such as that in Amalie Skram’s short story “Glæde” (Joy), from the collection entitled Sommer (1899; Summer), when the woman invokes death:

“‘Do not take me,’ she implored, ‘I must live and suffer. I must lie on a pyre for a hundred years to go from being an unworthy to a worthy.’”

Given that this is a case of countermeasure to the sexualisation of woman, it becomes difficult for the female writers to give body to the concept of worthiness. It seems that the body is particularly liable to be thematised in negative images and notions, such as in Camilla Collett’s depiction of the demeaned female body, of battered and frozen impoverished women in “Fra et mindre hjemligt Standpunkt”. In tales and everyday stories from the mid-nineteenth century, worthy womanliness is primarily given body through depictions of the woman’s environment – the everyday forum – and through the use of imagery. Metaphor gives body and physicality to Collett’s and Bremer’s mind portraits. A representative feature of Danish Thomasine Gyllembourg’s heroine in the tale “Drøm og Virkelighed” (1833; Dream and Reality) is that when she is ascribed worthiness, cultivation, and elegance of body, she undergoes a parallel loss of physicality, whereas her opposite number, uneducated Lise, is increasingly depicted in physical and corporeal terms the further she removes herself from worthiness and cultivation.

“My Laura was the soul of our circle, not that she ever claimed the least appreciation or took the lead in our conversations. Her jesting was, as jesting should be, pleasantly heartening, never wounding; her earnestness was full of reason and profound feeling. A gift for solace, for smoothing troubles, she always exercised, and she was an expert in mitigating the dark moods which from time to time still taxed my uncle’s disposition. When close to this kind of female nature, no despair or consuming disorder of the mind can readily take root.”

Thomasine Gyllembourg: “Drøm og Virkelighed” (1833; Dream and Reality).

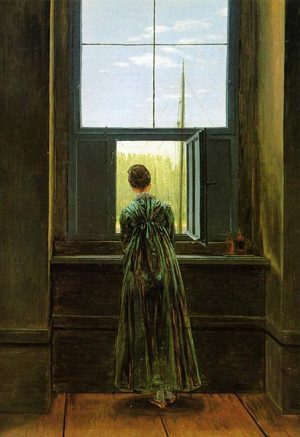

Female writers’ reflections on the contemporary prevailing ideality of woman and their own worthiness have to leave the body unexplicated, but portrayed and registered, within the figurative language of the stories, as Fredrika Bremer does in her prose sketch “Mit Fönster 1825. Besøket” (My Window 1825. The Visit). The story lets the descriptions from the living room visualise the body’s condition and yearnings. The story ends with the young woman no longer directing her longing towards the young men she can see from the living-room window, but towards God’s star, which sends its light straight in through the window, and the final picture emphasises that the young woman experiences a physical and mental harmony:

“It was as if the firmament was shining inside me, and when I walked past the pier glass it seemed to me that my eyes were shining bright as stars. ‘What does that mean? What has happened?’ I asked myself as I sat in the living-room sofa, contented to rest there and with an impression that something really had happened to me. There was a feeling of satisfaction, of inner independence in my soul, as if a truth, a light, full of the future, had risen therein.”

In her Christian reflections, on the other hand, and in descriptions of her faith experiences, Bremer often stresses the physical and corporeal aspect, as is the case of an account written in the 1840s about how nightly tussles with “painful memories”, “the bitterest sensations of my own as well as other people’s acts of folly” shake up body and soul. In a passage dated 6 August 1842, the idea of Christ’s ill-treated and wounded body is referred to as a healing thought: “As I pursued these thoughts, my heart filled with love for Him and in Him, and for His sake I loved my fellow creatures and – forgave myself. Peace entered my soul. A feeling of calm pleasure poured over my body, and at once, like a gentle lullaby, inside me the words: ‘In Christ’s wounds I fall asleep.’”

In the introduction to her account, Bremer links the experience to religious experiences depicted in devotional books, and she points out that even though they might seem unsavoury and “foolish”, her experience has taught her “to understand their profundity and recognise their meaning”. The body is a constant presence in Bremer’s religious reflections; even her use of religious language, which shows traits similar to the Pietistic style of hymn and devotional literature and the confessional writings of the medieval mystics, provides an opportunity to give the body direct access to verbal expression and rendition in words.

Use of religious language – which might, as in Bremer’s case, be related to Pietistic language or, as in Danish writer Elisabeth Hansen’s work, be akin to Romantic theology – was a means for the female writers to project the myth of worthiness via images of power, illumination, and salvation, and thus also of body.

“A medical regimen that I prescribed for myself during that period helped restore equilibrium to my entire being and some kind of inner contentment. I bathed often in lukewarm water, which produced an indescribably salubrious effect, and I submitted to blood-letting on several occasions. This drew out all the blood that had raced up to my poor head and made it so uneasy. Finally I applied fontanelles to both arms. They cleared up the rash on my face and removed all the pernicious fluids that had collected in my body for so many years.”

Fredrika Bremer in Sjelfbiografiska anteckningar, bref och efterlemnade skrifter(1831; Autobiographical Notes, Letters, and Papers)

In two short essays, “Romanen och Romanerna” (Eng. tr. “The Novel and the Novels”) and “Om Romanen som vår tids Epos” (The Novel as the Epic of Today), Bremer discusses her ideas on, her expectations of, and her objections to the art of the novel. The two essays are entertaining and well-written, particularly in Bremer’s use of metaphors when characterising the nature of the novel. With a fine, humorous distance, she enquires Romantically after the primordial novel, and it tells her its purpose by means of Christian-Platonic body imagery:

“I lift you in my arms above the earth and show you the battle that is being waged in the heart of man. Wherever you see armies meet, consummate under the banner of liberty, for better or for worse, wherever you gaze into humanity’s innermost history, illuminated by the torch of divine love, you will also see me – the novel.”

Bremer is happy to congratulate the novel on its purpose, and, if it is to be taken seriously and succeed, then the ultimate judgement will be found in what comes after the novel. But here, Bremer has to give free rein to her humour and argue that the most likely scenario is the arrival of new and yet more novels. In this manner, the two short essays proceed deftly on their way by means of a Christian-Platonic language that navigates a delicate balance between usage and exposure.

Camilla Collett makes it a special point in her writings to challenge the biblical phraseology that is always applied when the subject turns to woman. In her article on Alexandre Dumas in Fra de Stummes Leir (1877; From the Camp of the Mutes):

“It is strange to see how well versed in the Scriptures even the most godless of men become in matters pertaining to the disenfranchised sex, and when impeding some issue of progress in relation to this sex.”

At the same time, however, Collett presents her thoughts on worthiness and equality in a Christian terminology of fulfilment, illumination, truth, and purity. In her essay “Om Kvinden og hendes Stilling” (On Woman and Her Position) from Sidste Blade (1872; Last Leaves), the idea of liberation is structured as a Christian myth about the modern apocalypse, the last judgement, and the new world:

“A tremendous future lies before woman, a future that will give the world a different form. In times such as these, when the apocalypse would seem to have turned all its horrors loose, when there is pulling and tugging at every bond tying people to law and decency, it would be wise, if nothing else, to secure the woman’s sound, unused powers […] Her forgiveness is needed; there are crimes to be penalised, there is a curse to be overturned.”

Like another Moses, Collett looks into the Promised Land, although she does not think she will live to see it:

“Is this time far distant? I will not experience it. But I only know that whenever a man lifts his voice in support of our cause, thousands of these fruit-bearing seeds are shaken down, and we are drawn decades closer to fulfilment.”

Collett works energetically on using the Christian rhetoric in such a way that it can hold promise of and express the female myth of worthiness.

After 1900, female worthiness was given a new corporeal presence in women’s literature. In Marie Bregendahl’s marriage novel Holger Hauge og hans Hustru I-II (1934-35; Holger Hauge and His Wife I-II), for example, Kirstine is fully present in her body, whereas Holger – unworthily – is beside himself. Here they are getting married: “[…] so what had taken place in church had seemed to Kirstine both lovely and ceremonious.

“– It was different when remembering something that had happened a few hours earlier. – That was when Holger had come in and discovered that Kirstine intended to be a bride clad in a black dress. – How angry and crazy he had been, indeed, created a fuss to put it plainly […]

“It was fortunate that once she was all dressed up and had garland and veil on, he stood stock-still and looked at her with astonishment: ‘Why, how it becomes you Kirstine; you even look downright venerable ,’ he exclaimed in surprise – ‘almost like a clergyman.’”

Genius and Guardian Spirit

“Her natural virtue is not only grace, but also an innate dignity, proceeding from her invisible genius, her eternal individuality, and banishing from her proximity all that is common, unbecoming, and contrary to the finer sense of honour.”

Thus writes Danish Bishop Martensen (1808-1884) about “the male and the female nature” in the first volume of his Den christelige Ethik (1871; Christian Ethics). Martensen attempts to juxtapose the myth of woman’s innocence and the myth of her worthiness while at the same time endeavouring to naturalise worthiness as an innate characteristic of woman.

The keyword in this attempt at summing up worthiness and innocence is the female “genius”. Some of the women writers of the Romantic era view the matter differently. They see the myth of worthiness as a counterpoint to the myth of innocence, and they consider the idea of female genius to manifest a cultural female significance of far greater scope than that allowed by the formation of a zone of innocence around the graceful female body.

The Romantic theory of genius has its origin in the Greek notion of the personal daimon that intervenes in our lives with fortune or misfortune, in the Roman patriarchal notion of the paterfamilias as the embodiment of the family’s genius – its supraindividual idea or being – and in the Catholic doctrine of guardian angels and patron saints.

In the Romantic version, the ‘genius’ is primarily a representation of spiritual power that connects the human being in its physical world with its spiritual reality and mission. Fredrika Bremer links up her writing and her Christian reflections with encountering her genius:

“A good […], an affectionate genius, who in truth also carries on its divine caper amongst us, and who permits us success in our good intentions […] How often I have met it or sensed its invisible, lovely presence!”

Female prose writers of the Romantic era often give their women characters the role of the genius, or they feature as the tutelary deity in relation to the male characters. In Bremer’s “Tröstarinnan” (the Comfortess) from the second volume of Teckningar utur Hvardagslifvet (1828-31; Sketches from Everyday Life), a young man undergoes a crisis of faith; he throws himself to the ground in despair, and in his anxiety appeals to God in prayer; suddenly he feels a soothing hand on his head. He dare not look up, but imagines it is his childhood playmate, the dead girl Maria, who has come to take him home to God; a state of “peace and sweet serenity” spreads throughout his body and soul. But when the young man finally dares lift his face from the ground, he sees a woman of flesh and blood: his own sister, who has unexpectedly returned to their home. In “Tröstarinnan” the invisible genius is transformed into the living woman. This metamorphosis is found in a number of Romantic stories by women authors, but often in such a way that it is the living female character who enters into the position of genius or guardian spirit, whereas here Bremer proceeds the other way round and reveals the genius as woman. In the work of male and female writers alike, the Romantic notion of genius is habitually linked with the female, even though angels and tutelary spirits in Bremer’s Christian reflections, and in Hans Christian Andersen’s poems and Ingemann’s hymns, also feature as characters of the male sex.

In Hans Christian Andersen’s poem “Det døende barn” (1827; The Dying Child), the child imagines “angel-children smiling gladly” and then sees an angel, “one stands beside me now!”:

“See how his white wings beautifully glisten?

Surely those wings were given him by the Lord!

Green, gold, and red, are floating all around me;

They are the flowers the angel scattereth.”

As a male figure, the angel makes for a contrast to the child’s weeping and sighing mother; the angel’s sphere of children, flowers, and kisses also links it with the mother. Hans Christian Andersen’s angel would appear to be in a metamorphosis between male and female, parallels to which are found in the English oleographs that had found their way onto the walls of many a nursery room in the course of the nineteenth century.

Why dost thou clasp me as if I were going?

Why dost thou press thy cheek so unto mine?

Thy cheek is hot, and yet thy tears are flowing!

I will, dear mother, will be always thine!

Do not sigh thus – it marreth my reposing;

But if thou weep, then I must weep with thee!

Ah, I am tired – my weary eyes are closing –

Look, mother, look! the angel kisseth me!

From Hans Christian Andersen’s poem “Det døende Barn” (1827; The Dying Child).

In Ingemann’s Morgensange for Børn (1837; Eng. tr. Morning Songs), the angels also feature as embracing, maternal male figures; as, for example, in “Lysets Engel” (Angel of Light):

“Us as well he will embrace,

Daylight’s blessed bringer,

Show to us his smiling face,

Heaven’s God-sent all-embracing winger.”

In his poem about the child’s guardian angel, “Hulde Engel” (1825; Faithful Angel), Blicher does not refer to the angel as a ‘she’ or a ‘he’; however, the Romantic usage of the adjective “hulde” (faithful) in itself largely connects the angel with the female sphere:

“Faithful [hulde] angel, you my childhood friend!

Loyal companion in the bygone days!

Tell me do – where have you gone?

Tell me when – when will you return?”

A metamorphosis between male and female would seem to predominate in lyric poetry and songs about angels and geniuses, whereas the geniuses and guardian spirits of Romantic everyday stories and novels mainly feature as female figures. In these works, the idea of the genius seems to provide the woman with a significance that places her at the centre of culture and society; but the idea of the genius can also cast a divine light on the woman’s role in an intimate Biedermeier universe, where the woman cherishes and protects the home and family. The latter is the case with Hanna Winsnes’ novel Det første Skridt (1844; The First Step), in which one of the female central characters is simply introduced as a guardian angel:

“We have, thank God, the happy belief that invisible angels hover around us and aid us in the struggle of life; but it is not only invisible beings that the Lord sends to the assistance of his chosen ones – among our fellow human beings there are also fair spirits with such a beneficial influence upon our minds and such a wonderful power over our predispositions that we must call them our good angels.

“A good angel such as this was Elise Rein for Alexander.”

Due to the idea of genius, the woman thus bears a cultural worthiness and truth that should belong to society as a whole; the idea of genius also, however, consigns the woman to the domestic Biedermeier universe as the reconciler of opposites, the handmaid of harmony and family.

The high rhetoric employed by Swedish Bishop Wallin with reference to the woman’s noble and serene calling, together with Danish Bishop Martensen’s construction of woman’s disposition, restricted the woman’s liberty of action to the parlour cosiness and hearth idyll of Biedermeier culture; but Romantics such as Bremer, Collett, and the Danish writer Mathilde Fibiger could not reconcile themselves with either the high theological rhetoric or the idyll of the parlour. They considered the female genius to be of radical significance, and this they projected in their personal interpretations of Romantic and Christian meanings and terminologies. Bremer would happily have let the female genius prevail throughout society and culture, and she envisaged a new female era – one which she thought was already dawning in the Nordic region. The sight of the childless Danish queen, Karoline Amalie, surrounded by children of the poor at one of the ‘children’s asylums’ evokes a vision of a new maternal epoch. In her essay “Lif i Norden” Bremer thus writes:

“It was a beautiful picture. And what I saw here was an image of life, a movement that is currently passing through society in the northern lands. It is the women’s, the mother’s, movement in society, which unfolds to embrace a wider circle, to care for children outside their own home, and to save and raise up to their own all the unfortunate little ones. It is the principle of motherhood extended beyond the life of the individual person and into the public in order to form a new home.”

In Clara Raphael. Tolv Breve (1851; Clara Raphael. Twelve Letters), Mathilde Fibiger also expresses the idea of a new spiritual societal home. During the emotional days of war in 1848, Clara Raphael experienced an intense feeling of solidarity with her nation. The private, the familial, and the national and public spheres merge together:

“No, I am not alone! God is my Father, Denmark my mother; all people are my brothers and sisters. This is the great family life in which I have taken root.”

In the essay “Om Kvinden og hendes Stilling”, Camilla Collett intensifies her argumentation on the female genius and the social family. She points out that woman is by nature genial (of genius), but that this genius has become a dangerous force, because woman must not use her genius in “any major, socially influential respect”. The spurious female profile, the characteristics of which are deceit and cunning, arises when the genius is locked up in “the local, the shadowy, the hidden”. The good female profile is the natural force of genius in woman, her “fortune-bringing abilities”, which ought to be of benefit to the whole societal family. Based in the Romantic notion of genius, Bremer, Fibiger, and Collett all endeavour to describe woman’s social assignments.

In their everyday stories, essays, and novels, the female Romantic prose writers had to express themselves in relation to a male Romantic rhetoric that, in the work of theologians such as Martensen and Wallin, served to provide the myth of innocence with substance and sociality in the bourgeois home. But a religious language and a religious scheme of things also played another role for women. As the century progressed, some peasant women began to take part in the new revivalist movements and religious groupings such as the Haugeans in Norway, the new Free Churches and religious communities in Sweden, and the evangelical Indre Mission branch of the Danish Church. The new Nordic revivalist movements often had an oppositional voice in relation to a prevailing ecclesiastical institution, and the movements provided an opportunity for women to become acquainted with the written word. Their memoirs, testimonies, and hymns bear witness to the circumstance that the revivalist movements and the new religious groupings gave women different and more active roles in the life of faith than did the dominant institution of the Church.

It is from the platform of a Christian culture’s language and scheme of things that the Romantic women think and write – whether they like Swedish Fredrika Bremer make the relationship with God the starting point for an artistic creation, like Norwegian Camilla Collett look with literary and polemic eyes into the true woman’s promised era, like Danish Elisabeth Hansen write their version of the mystical-religious psychology of the day, like Norwegian Hanna Winsnes portray the capable wife and mother, or whether like the Norwegian Haugean Berthe Canutte Aarflot they write hymns for the redemption of the soul.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch