Over the centuries, the popular ballad tradition has been carried by women and men alike. Testimony to this, with reference to the sixteenth century, is found in Hundredvisebogen (1591; One Hundred Ballads), compiled by Danish historiographer and clergyman Anders Sørensen Vedel:

“For what can be a better pastime than these lovely songs […] to say nothing of the delightful tunes to which they are sung by those who can, this in itself gladdens the heart when they are sung with a pure female voice or a strong male voice.”

“Thi huad kand giffue en ærligere eller sømmeligere Tidkaart, end saadane smucke Viser … At ieg nu intet vil tale om den subtilige og søde Melodi, som de siungis met, aff denem som vide Tonen til dennem, huilcket i sig selff fryder it Menniskis Hierte, naar de ellers quædis met en reen Quinde Stemme eller sterck Karl Røst.”

In a letter written 330 years later and addressed to folklorist and ethnomusicologist Hakon Grüner Nielsen, the Danish ballad singer Selma Nielsen remarks of her family’s singing tradition:

“I had no idea that Redselille had been printed; my father, who is 64 now, learnt it from his mother when he was a child, and it was already a very old ballad back then.”

Although not specifically a women’s tradition, it nonetheless makes sense to refer to women informants because each narrated version of a ballad is a fixed point in an often very long tradition, and because this fixing can result in a personal, female shaping of the ballad’s narrative, the sung story.

Looking at the changes undergone when a ballad passes from female to male informants and vice versa, however, we often find that these are determined by generation rather than by gender. Ballads dealing with women’s circumstances – the anguish of childbirth and rape – are sung by women and men alike; these are human tragedies affecting the whole family. Historical facts relating to high maternal mortality rates and statements pertaining to rape and incest in articles of Common Law and court records show that narratives in the traditional ballads were based on actual events.

The oldest extant source material of the Nordic tradition goes back to the early sixteenth century, but there can be no doubt that it built upon an even older tradition. It is impossible to imagine a culture devoid of storytelling, song, and dance. The existence of fragments of medieval ballads, similar in type to the folk ballads with which we are generally familiar, bears witness to a long tradition.

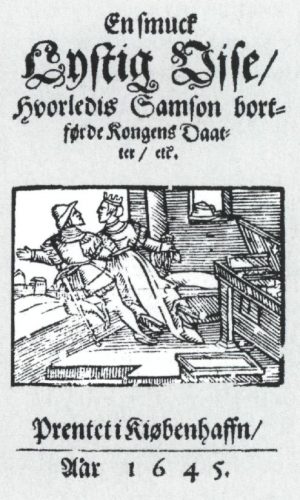

The ballad sheet, introduced in the early 1500s, with the words of one or more ballads, often of a topical and satirical nature, was to have great significance for the tradition. These printed sheets or pamphlets, which needed prospective markets in towns and at fairs, were not a feature in Iceland and the Faroe Islands, but they were widespread in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden – the popular nineteenth-century “broadside ballads”.

The first handwritten ballad books appeared in the mid-sixteenth century in Denmark and Sweden and were compiled by aristocrats, clergy, and scholars. A century later we find the first ballad book in Iceland, the source of which was most likely an even older but no longer extant ballad book. The number of ballad manuscripts swelled during the seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth century. Some of the surviving copies contain examples of the lyrical and religious high-literary tradition of their day; the collections mainly consist, however, of ballads and songs with a narrative content, most being in the genre defined as folk ballad.

The narrative ballads are presumed to be rooted mainly in the early oral song tradition of the aristocratic, commoner, and peasant environments; some, however, bear the stamp of having a written or printed source. The ballad sheets or pamphlets played a major role in what was committed to paper in the ballad manuscripts; in many cases the characteristic front pages of the ballad pamphlets, with information about melody and date of printing, were transcribed along with the ballads.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the ballad book tradition was largely taken over by the peasantry. The many printed versions of ballads made during this period, along with the growing tradition for printing pamphlets, had an impact not only on the content of books of rural ballads, but naturally also on the oral, sung tradition in which the ballads could be passed on between family members and between work colleagues. Popular song was especially buoyed up by the small books of ballads produced for use in schools. The systematic collection of the ballad tradition manifested in a number of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century ballad manuscripts was repeated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – this time in all the Nordic countries. While the manuscripts, earlier as well as later, only contain melodies for a few of the ballads, collectors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries endeavoured to write down tunes along with texts.

Even though much Nordic ballad tradition of the last four hundred and more years has been lost, the surviving tradition represents an overwhelming amount of source material. The intense registration and publication work undertaken during the last century and a half has resulted in an overview of the Nordic tradition via a number of critical studies and annotated editions: in 1972 the Faroe Islands completed the collection Corpus Carminum Færoensium, Føroya kvæði I–VI (Faroese Ballads); in 1976 Denmark concluded the collection Danmarks gamle Folkeviser I–XII (Denmark’s Ancient Folk Ballads I-XII), having already completed the publication of the lyrical ballad material from the manuscripts in Danske Viser I–VII (1931; Danish Ballads I-VII); and Iceland followed in 1981 with the final volume of Íslenzk fornkvæði I–VII (Icelandic Ballads I-VII). For several centuries, Norway and Sweden have, like Denmark, published ballads based on various sources, but in 1982 Norway published the first volume of a projected complete collection of Norske mellomalderballadar (Norwegian Medieval Ballads), and between 1983 and 2001, Sweden published Sveriges medeltida ballader (Sweden’s Medieval Ballads), a scholarly edition in five volumes.

In Nordisk Folkeviseforskning siden 1800 (1956; Scandinavian Ballad Research since 1800), Erik Dal defines the basic ballad form as two- or four-lined stanzas of each three or four stressed syllables, rhymed aa or xaya, invariably with a refrain at the end of the stanza (a burden), sometimes also with an internal refrain (alternating with the lines of the text), and possibly a repetition of the last part of the stanza, known from the early aristocratic tradition and the later post-1800 popular tradition.

The extensive corpus of material on which these editions are based contains songs that were sung by and about women. From the host of female singers, collectors, and scribes, we will here select ballads dealing with women’s personal and fundamental experiences – experiences with critical bearing on family and lineage: seduction, rape, distress in childbirth, and infant mortality are the subjects of the more than four centuries old tradition of song treated of in the following.

The extensive scholarly undertaking The Types of the Scandinavian Medieval Ballad: A Descriptive Catalogue 1978, eds. Bengt R. Jonsson et al., provides an overview of Scandinavian ballads, grouped and numbered by ballad type.

Ballad Manuscripts in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century ballad manuscripts are reliable sources in themselves, but we can only speculate about their sources. As mentioned, some of the ballads in the manuscripts show signs of being transcriptions from broadsides or pamphlets. On the other hand, we know little of the sources for the ballads presumed to have been written down from the oral, perhaps sung, tradition in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. We do not know the identity of the informants, and therefore cannot know if they were men or women. Thus, we must look at the next step in the process: the collector who recorded the ballad in the manuscript. A very few manuscripts allow for identification of the compiler, perhaps the scribe. Notes made in other manuscripts, however, tell us who the owner or owners have been, although they will not necessarily have had any significant influence on the content of the ballad book itself.

Notes and names entered in the Danish and Swedish manuscripts show that an occasional ballad might have been recorded – and at any rate known – by women. However, if we want to study ballad manuscripts that are almost guaranteed to have been entirely selected and compiled by a woman, we must turn to three seventeenth-century Danish ballad collections: Anne Krabbes Visebog (Anne Krabbe’s Ballad Book), which has only survived in a later copy; Christence Juuls Visebog (Christence Juul’s Ballad Book); and Vibeke Bilds visesamling (Vibeke Bild’s Collection of Ballads), consisting of several manuscripts, of which three survive.

Female informants on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Swedish and Icelandic soil cannot be identified with any certainty. “We do not have any aristocratic books in which ballads have been written down as the result of pronounced genealogical interest, as is the case with Anne Krabbe’s Danish collections,” writes Bengt R. Jonsson in Svensk Balladtradition (1967).

These Danish aristocrats – Anne Krabbe, Christence Juul, and Vibeke Bild – were related, and all three were privileged in terms of their folkloristic and literary interests, given that their childhood homes and married homes were part of a learned and literary milieu. Anne Krabbe and Vibeke Bild were left to run their estates after the deaths of their husbands, which means that they were presumably in direct contact with the culture of the peasantry. The ballads and poems they collected thus provide an account of the seventeenth-century peasant song as well as of the song and writing of the nobility. Both were widows by the time they collected their ballads, whereas Christence Juul was a young woman when she compiled her ballad book. Her manuscript therefore naturally has the look of an ‘autograph book’, containing a number of copies taken from the ballad books of relatives – including that of Anne Krabbe.

Folklore Collector Anne Krabbe

Anne Krabbe was born in 1552 at Aastrup estate in the Voldborg district. She was the daughter of Margrethe Rewentlow and Erik Krabbe; in 1588 she married Jacob Bjørn til Stenalt, from Randers County.

Anne Krabbe was interested in history. This interest is reflected in her ballad manuscript: she wrote introductions to fifty-four of the eighty-eight ballads, identifying the location and often the date of the ballad and providing information about the characters. She seeks to cast light on the background of the ballads by visiting localities linked to the storylines. In cases where the characters are authentic historical persons – and often even members of her own family – background information is of course available; it is noteworthy, however, that she visits – in her own words – “old folk” who can tell her stories and point out locations as background for the non-historical ballads.

One good illustration of this is the ballad about “Ribold og Guldborg” (Ribold and Guldborg). In her manuscript, Anne Krabbe introduces the ballad thus: “Here follows a lovely old ballad about the pagan daughter of a king from days of yore, Mistress Guldborg, who was carried away from Kalø but overtaken at Rosted Mark, which is near Følge Mill. Many were killed for her sake, and there lie they buried. Their graves are still known to this very day. It happened in the time of giants. I, Anne Krabbe, Jacob Bjørn’s widow, have myself attended these places on April 4th 1605, where old folk told me that Ribolt’s mother lived on the farm that lies near Rugaard in Sønderherred, and there Ribolt led her to his mother. And there they lie buried outside the farm. And large stones are placed around them, which I myself have seen. Anno 1615.”

She writes a postscript linking the ballad to her own era by telling us that Rugaard has now been turned into two farms, which she visited in 1606.

Anne Krabbe calls the ballad “old”, but she does not venture a more precise dating, merely “the time of giants”. She is extremely specific in telling us the dates of her visits to localities in which, according to old people, the story took place. There can be no doubt that she assumes a kernel of truth in the narrated and sung legend, and she is very keen to record the ballads as stories about people who once lived. This approach, so characteristic of her as collector and scribe, creates a connection between song, story, and human existence. In the same way that her informants narrate the legends behind the ballads as true stories, the collectors’ sources turn their two-to-three centuries old ballads into stories about real life.

Christence Juul and Her Autograph Book

Christence Juul was married to Anne Krabbe’s nephew, Hans Krabbe. She was born in 1585, the eldest of four siblings; her sister Kirstine Juul possibly owned, but had probably not compiled, another ballad manuscript, named in the archives as Karen Brahes Kvart (Karen Brahe’s Quarto). Her parents were Kirsten Ovesdatter Lunge and Niels Axelsen Juul til Kongstedlund, Aalborg County.

In Christence Juuls Visebog, which contains fifty-six ballads, there is a borrower’s ‘receipt’, showing that the written ballad books also interested those members of the family who had apparently not made their own ballad manuscripts:

“This book belongs to Christence Juul. I, Berete Vind, borrowed the book on February 13th 1617.”

Even though the ballad book contains a number of copies made from the books of older relatives, including Anne Krabbe, Christence Juuls Visebog is essentially different to, for example, Anne Krabbe’s book. While Anne Krabbes Visebog, with its attempts to get behind the active participants in the ballads, shows a sense of reality and outgoing approach on the part of the collector, Christence Juuls Visebog reflects a young woman’s poetic and more introvert urge to give the book a personal touch by means of lyrical, religious, and occasionally moral maxims, at times written in code. Christence Juul might complete the entry of a ballad with a little stanza such as this one:

The red rose doth sweetly smell,

with God and honour you should be content,

speak decently, and be modest,

heed well [?], what you here gather,

The rose fades, you grow old

My friend, grow wise, it is honourable for you,

that you learn, to the glory of God.

Rosenn rødt, Giffuer Lucten sød,

med gud oc ærre, Du glad mon were,

tall tuctige Snack, Og tag till tack,

før e vdenn dør, Huad du her hør,

Rosenn forfalder, Du sancker alder

Minn wen bliff wiss, det er dig pris,

Attu Nogedt Lere, Gud till erre.

Or she will write a brief rhyme, such as this one inserted below the ballad about “Harpens Kraft” (The Power of the Harp):

Fortune comes,

Fortune goes,

He who fears God,

will have fortune to hold.

Christence Juul does not follow Anne Krabbe’s approach of trying to make the characters ‘real’, preferring to use the ballads as an opportunity or stimulation to tell about herself and about what she ought to do. A light and sunny outlook runs through her choice of ballads, and songs with a happy ending are in the majority.

The book is elegantly written in Christence Juul’s hand, with the exception of the opening and closing texts which were written by her second cousin Olivia Lykke. A maxim such as the following, entered by Olivia Lykke, leads our thoughts to the autograph books of later centuries: “1614. Fear God, live a Christian life, / the Lord shall surely help thee. Olivia Lykke. By her own hand.”

Ballad Collector Vibeke Bild

Vibeke Bild was born in 1597, the daughter of Anne Kaas and Preben Bild. In 1613 she married Erik Rantzau til Gjessingholm, Randers County; he died in 1627, after which she first lived on her estate of Aggersborg in Hjørring County, and then, from 1631, she spent some of the time at Lundgård with her mother, and some at Tårupgård, both in Viborg County. Vibeke Bild died in 1650.

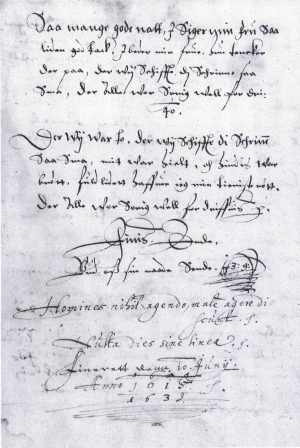

She made her collection of ballads in the 1630s and 1640s; as mentioned earlier, she collected enough for several ballad books – at least five, of which three have survived – making for a collection of more than 300 ballads in all. The most personal of the three extant manuscripts is the ballad book in landscape format, named in the archives as Vibeke Bilds Kvart (Vibeke Bild’s Quarto). The book has the following inscription on the inside of the binding:

“This book belongs to me, Vibeke Bild, Erik Rantzau’s widow and I bought it in Copenhagen last Thursday after the wedding of my brother-in-law, Henrik Rantzau. And I will make of it a little ballad book for pleasure and pastime. Written in Copenhagen, June 30th 1631.

“Everything is transitory, only the grace of God remains for ever and ever. Vibeke Bild. Erik Rantzau’s widow. Own hand.”

Thirty-five years later, and sixteen years after Vibeke Bild’s death, Mette Grubbe gave the book as a gift to Brostrup Gedde, whom she wished – but never managed – to wed. The gift was accompanied by the inscription: “I have made this book for Brostrup Gedde, as a humble gift. Were it bound with precious stones, as this is with leather, he would, I know, be fully deserving thereof. Rasch, March 28th 1666. Ebbe Ulfeldt’s widow, Mette Grubbe.”

The first two-thirds of the book are used as an autograph book, in which Vibeke Bild and her female relatives and circle of acquaintances have entered poems and ballads along with maxims and their names. The maxims are somewhat akin to those in Christence Juuls Visebog. Below a number of ballad entries, Vibeke Bild has written a short stanza showing that the ballads in the book have been the object of shared pleasure:

“The end. May God’s grace be upon us / God bring joy to the one who wrote the ballad and also all those who performed it.”

One of Vibeke Bild’s entries, “Visen om Niels Påskesøn og Lave Brok” (Ballad of Niels Påskesøn and Lave Brok), is about a killing that took place in Randers in the year 1468, thus showing that, like her relative Anne Krabbe, she can be interested in a ballad with a historical source. The story is based on a real event in the part of the country where she lived during her marriage, and it is either a local ballad passed on orally or it could have been copied from a ballad sheet tale derived from an existing document about the case. In a long list of lyrical ballads in the same book, Vibeke Bild has entered the love ballad “Der sttander eet tthree vd for vor gar” (A Tree Grows Outside our Courtyard). The ballad is addressed, as is apparent from the following selected stanzas, to a man:

“A tree grows outside our courtyard,

still in my heart it flourishes

with lovely branches.

And would my dearest understand,

he would send me fruit thereof,

he would never let me die.

His name is with a K with crown above,

Christ bless him in whom I trust,

od keep his life and honour.”

Der sttander eet tthree vd for vor gar,

ydelig i mit hiertte sttar,

besatt med edelige grenne.

Och ville min aller kierstte ttenke ved sig,

vd aff den fruct sende hand mig,

hand lod mig aldriig farfarre.

Hanss bogstaff er itt (kronitt) K,

Chrestt signe hannom, der ieg vell ttro,

Gud beuare hanss liff och ere.

The presumed source for this ballad is found in a ballad book from the 1550s, in which an older relative, Jens Bille, has entered a version addressed to a woman:

A tree grows inside our courtyard,

with honour and virtue it is preserved,

with precious branches.

And would my dearest friend but comprehend,

how the sorrow of love oppresses me

both in secret and abroad.

Her name is with a crowned M,

Christ bless my friend, well I know whom,

Christ bless her life from harm.

Ther stander ett thræ forinden wor gaar,

mett ære oc dygtt er thett beuartt,

mett dyrebar grenne.

Och wylde myn kiæriste wenn thencke wed siig,

huor ælskoues sorriig hun tuinger mig

baade lønliig oc obenbare.

Hendis bogstaff er ett krunit M,

Christ siigne myn wenn, ieg wed well huem,

Christ siigne hendis liiff frann waade.

At other junctures in the Danish and Swedish ballad book tradition, we find a similar toying with lyrical love ballads in which the name of the object of desire is hidden in the text or revealed in an acrostic, and in which, by means of slight adjustments, an originally traditional ballad becomes the writer’s own composition.

The last part of Vibeke Bilds Kvart and the two other extant manuscripts in Vibeke Bild’s name were written by her employed scribes. At the same time, the content changed character in some measure, given that the works copied were now mainly from ballad sheets and pamphlets, both Nordic and German. Vibeke Bild thus presents herself as a collector of the tradition and her manuscripts are some of the best source material for research into the cross-frontier pamphlet and ballad sheet tradition, later to be known as the broadside tradition.

Three Ballads about Women, Recorded by Women in the Seventeenth Century

A traditional ballad often has a lengthy history; each recorded version can be considered unique because the informant has a degree of active input. It is therefore important to have a viable identification of the informant. Based on this criterium, the following three ballad versions have been selected to shed light on a few aspects of the traditional ballad in the seventeenth century:

Anne Krabbe’s version of “Sune Folkesøn”, a ballad about the abduction and rape of a woman. The ballad, based on actual historical events in Sweden, has been handed down in Danish and Swedish ballad manuscripts from the 1500s and 1600s, and in Swedish ballad sheets and pamphlets from the 1600s.

The motif for the storyline in the Nordic folk ballad tradition is most often that of destiny. The ballad of “Sune Folkesøn” highlights the woman’s hereditary, and thus pre-destined, suffering.

Christence Juul’s version of “Hustru og Slegfred” (Wife and Mistress), a ballad about the anguish of childbirth. The ballad has been passed down in a number of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Danish manuscripts. A related ballad, “Hustru og Mands Moder” (Wife and Mother-in-Law), has been handed down in the nineteenth-century Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish peasant tradition.

Vibeke Bild’s version of “Herr Ebbes Døtre” (Sir Ebbe’s Daughters), a ballad about revenge for rape. The ballad, entered by Vibeke Bild’s scribe, survives in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Danish and Icelandic manuscripts and in the Icelandic peasant tradition of the nineteenth century. The same ballad is recorded and annotated by Anne Krabbe.

Songs about Abduction and Rape

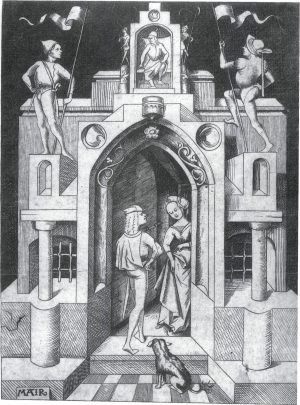

The traditional ballad frequently deals with maidens who are abducted from their temporary, sheltered setting in a convent. The abductor might be a wooer whose intentions tally with the wishes of the maiden, and in these ballads – which, with their disrespect for monastic life, clearly reflect the age of Reformation – the abduction from the convent is accepted with good cheer:

“All the convent maidens stood

reading in their books, they thought

it had been an angel of God

who had carried her away.

All the convent maidens sat

thinking each alone,

‘If only God the Father in Heaven,

He would fetch me thus.’

Thanks shall Sir Morten have,

he did indeed his promise keep,

he took her to his farm,

he let his wedding be.”

Alle da stod di Closter-Iomfruer

och leste i dieris bog,

de mentte dett haffde veridt en gudtz Engell,

der hinde førde bordt.

Alle daa sad di Closter-Iomfruer

och tenckte huer wed sig,

giffue gud fader i Himmerig,

hand wille saa hentte mig.

Thack haffue her Mortten,

saa well holt hand sin tro,

hand førde hinde till sin egen gaardt,

hand lod sin brøllup boe.

Thus Christence Juul ends her version of the ballad about “Hr. Mortens Klosterrov” (Sir Morten’s Convent Abduction). However, other ballads about abductions from convents, the ones that go against the woman’s will, take an entirely different stance.

The abductor in “Sune Folkesøn” has no intention of marriage. The ballad tells the story of violent and degrading cohabitation and of children taken away from their mother.

Historical fact underlies the ballad: Sune Folkesson, who was descended from the Swedish Folkunga dynasty, was married to Helena, daughter of King Sverker II of Sweden. They had two daughters, Katarina and Benedikte. An anonymous and most likely incorrect early fifteenth-century chronicle, Cronologi anonymi, mentions a third daughter who was supposedly abducted in 1245 by one Laurentius, but there is no reference to this daughter in the family documents. Sune Folkesson’s and Helena’s daughter Benedikte had three daughters; in 1287, the eldest, Ingrid, who was engaged to the future High Justiciar of Denmark, David Thorstenson, was abducted to Norway by one Folke Algotsson. Ultimately, she returned to Sweden, where she and her sister were Abbesses at Vreta Convent.

The ballad draws on historical events, which are ‘shared out’ – incorrectly – among the historical characters: Sune Folkesøn abducts Elena, who is the daughter of King Magnus of Sweden, from Vreta Convent. In the ballad tradition, their two daughters have different folk ballad names. Of the one, her mother foretells that she will be abducted and violated – as she herself had been. In Anne Krabbe’s version of the ballad, the setting is Denmark; Elena’s father is the Norwegian-Danish King Magnus the Good; the Swedish Vreta Convent becomes the Danish Vredløv Convent in Vendsyssel; we learn in the introduction:

“A lovely old ballad made about King Magnus of Denmark’s daughter, who was called Miss Elin, and who Sune Folkesøn abducted from Vredløv Convent in Vendsyssel, the story of which is told in the ballad. This same King Magnus was also king of Norway. And there he fell from his horse and was killed and was later buried in Trondhjem Church.”

Although Anne Krabbe assigns her version of the ballad to named locations in Denmark, mostly in Jutland, there is no reason to assume that she had any specific purpose in making the abductor Swedish and the injured family Danish-Norwegian. She must have known that Sune Folkesson (her Sune Folkesøn) was a descendant of the Swedish Folkunga dynasty, but she never makes direct mention of the fact that he is Swedish. However, Anne Krabbe’s rendering of the ballad – which in all its Danish and Swedish versions tells the story of a woman’s defiled and tragic life – is also full of righteous anger.

Elin (that is, Helena) might indeed be in the safety of a convent, but she is nevertheless the target of attack as a consequence of her father’s absence through illness and death. When Sune Folkesøn tells his men of his intentions, they try to stop him:

“If we ride to Vredløv Convent

and violate that maiden,

and if King Magnus does hear

of it, he will be the death of us.”

Rider vi thil Wreløff-closter

och skiender vi den møe,

fornemmer det Magnus koning,

da bliffuer hand wor død.

But he responds:

“No longer since than yesterday

did I hear,

that King Magnus is dead,

and that his body lies on the bier.”

Det er iche lenger siden i goer,

ieg den thidende spurde,

at koning Magnus hand er død,

hans lig det liger paa bare.

It is clear that Elin is carried off against her will:

“Bare-headed and bare-footed

she walked out of the door

never did I hear a king’s child

depart a convent in such grieving.”

Oben-hoffuit och bare-foed,

kom hun aff døren ud,

aldrig hørde ieg it kongens barn,

saa sørgindis aff kloster komme.

And it is equally obvious that the abductor’s intentions were not good, and it was not happiness that awaited her:

“Sune Folkesøn it was,

he took her to his castle,

in all truthfulness I must say:

he caused her grief every day.

It was fair Elin,

it was her greatest anguish,

the first night she had the convent

left, so slept she in his arms.

They were together for winters,

a full winters nine,

never felt she so ill nor well

that she spoke with him those years.

They were together for winters,

a full winters nine,

with him she had the daughters three,

them she was never allowed to see.”

Det war Sonne Falckuorsen,

førde hinder til sin egen borig,

det wil ieg for sandingen sige:

hand giorde hinder dagelig sorigh.

Det war skiønne Ellin,

det war hindis største harum,

den første nat, hun aff closter kom,

da soff hun paa hans arum.

Di war thilsammen i wintter,

i fulde wintter nii,

aldrig war hun saa wee eller vel,

hun thalit thil hannem i di.

Di war sammel i wintter,

i fulde wintter nii,

hun fich med hannem di døtter threi,

hun maatte dennem aldrig see.

After nine years of inhuman cohabitation, Elin falls ill. She sends for Sune and lists all the atrocities she has suffered: abduction, rape, the taking away of her children. To this she adds the memory of yet another humiliation:

“You have taken my servant girl

and laid her on the blue bolster,

you have pushed me from the bed

and out onto the bare straw.”

I haffuer thaget min thienneste-møe

lagt hinde paa bulster blaa,

i haffuer mig aff sengen skutt,

udi di bare straae.

Sune Folkesøn asks for forgiveness; however, common to all the versions of this ballad, the woman will not forgive. This diverges from the norm in the folk ballad genre:

I cannot forgive you

all the pain you have caused me,

I have borne three daughters with you,

but them I was never allowed to see.

Ieg kand eder iche forlade

alt for saa møgen wee,

ieg haffuer fanget med eder di døtter threi,

ieg matte dennom aldrig see.

Still more tragic is her prediction of her daughter’s fate:

[…] you shall inherit the grief

from your dear mother.

You shall enter a convent

with but your silk shift,

from there you shall be abducted

with but your deep-felt grief.

… du skalt sorigen arftue

effter kiere moder din.

Du giffuer dig i kloster

alt med din silche-serch,

du bliffuer der udtagen

alt med stor hierttens-werch.

In places, the ballad about Elin and Sune Folkesøn deviates from the stereotypical narrative form, and where this happens we learn of realistic and significant circumstances.

Songs about Childbirth

Childbirth provisions were so primitive, even for the highest social class, that complications during delivery inevitably resulted in the woman’s death. Delivery was a woman’s matter, as is pointed out in an eighteenth-century pamphlet ballad “Redselille og Medelvold” (Redselille and Medelvold). When the anguished woman groans “My mother she had the women nine, / Christ grant, I had but the least of these,” the putative father tries to help: “Bind you a cloth before my eyes, / So will I help you just like a woman.” But her reply and the consequence hereof is: “Before man should know of women’s anguish, / Far sooner would I in the green meadow die.”

The horror of difficult childbirth is described in a short related ballad, “Bolde hr. Nilaus’ Løn” (Bold Sir Nilaus’ Reward), which has only survived in the seventeenth-century Ide Giøes Visebog (Ide Giøe’s Ballad Book) as told by an anonymous informant (probably from Jutland):

He lifted little Kirsten up from the earth so hushed,

of huge sorrow her heart would surely break.

So far and wide it could be heard

how her infants under the husk did scream.

He laid little Kirsten in the earth so hushed,

he laid a son on each a breast.

Han løffte liden Kiersten paa iorden saa tyst,

aff stor sorrigh hendes hierte monne bryste.

Der thatte mand høre saa langt under leed,

huor hinne smaa børn unnder skallen skreegh.

Hand laa liden Kierstenn i iordenn saa tyst,

hand laa en søn paa huert it bryst.

In Christence Juul’s ballad about “Hustru og Slegfred” all the anxiety associated – for good reason – with pregnancy and childbirth is highlighted by the notion that the pregnant woman, Kirsten, has been bewitched by a jealous female rival. The real cause of women’s distress in childbirth creates an impotent fear of that which cannot be influenced, but in the song this fear is given a shape that can be fought against – and the ballad ends happily. The young Christence Juul, to whom the ballad meant so much that she signed her name below it, shares the story with thirteen other ballad collectors and scribes. The versions are not identical, but they are so similar that it seems likely that copies of the ballad were in circulation.

The storyline in Christence Juul’s twenty-six-stanza ballad is thus: Sir Iver becomes betrothed to the maiden Kirsten, marries her, and makes her pregnant on their wedding night, but Iver’s former mistress casts a spell on the conception: “His mistress then made it so, / that she would never have the child […] / While she remained on this island.” Forty weeks later, Little Kirsten goes into labour:

They plagued her both without and within,

her torment did not lessen.

As I cannot get any better,

then take me there whence I came.

Dj fulde hinder baade ud og ind,

icke bleff hinders pinne dess minder ….

Mens ieg kan icke beder faa

daa fører mig did, som ieg kom fraa.

When Kirsten arrives back home at her mother’s – on foot because, in an attempt to stop her going, Iver has said that she must ride neither horse nor carriage – her servant girl tells her the cause of her maternity complications – not the real cause, but the song’s cause, which is personified and can be fought against: “She [the mistress] then made it so”. Then things get busy in Little Kirsten’s childhood home, but when Kirsten asks everyone to pray to God on her behalf, her mother replies:

Hurry to light the candle,

no sleep be here tonight.

My darling daughter, do not fear,

your hard band [meaning: that you cannot give birth], it will surely be untied.

I tender nu op Liusset brat,

her will icke soffues i denne Nat.

Min kierre Datter, wer wed god trøst

din haarde baand, den bliffuer well løst.

Kirsten gives birth to the baby, and when Iver hears the good news he exclaims: “Praised be the Lord”.

The ending to Christence Juul’s ballad departs from the other versions. In these versions, the mother is drawn into the happy event, as in this example from Karen Brahes Folio (1570s): “All the joy Sir Iver had / was because Mettelille [the same as Kirsten] went to her mother.”

The clear message in this version is that the older experienced woman can help the young pregnant woman through the distress caused by a difficult and potentially fatal delivery. The role of helper is here performed by the pregnant woman’s mother, thus emphasising the value of lineage, of family. A ballad that addresses this aspect of the predicament can end happily.

The evil, however, still has to be rooted out, and Christence Juul, like the other informants, ends her version with: “He had his mistress burned to death”.

Songs about Women’s Revenge for Violence Done

In the ballad book that she and her female friends and family wrote, Vibeke Bild includes a ballad about a woman’s quite absurd patience. The ballad about “Den taalmodige Kvinde” (The Patient Woman), recorded uniquely by Vibeke Bild, has correlations with the Griselda motif: a woman is tormented and humiliated by a man testing her to see if she is patient enough to be his wife. The Little Kirsten of the ballad passes the test, but nonetheless expresses criticism when faced with a woman she believes to be a new mistress, but who is actually the daughter she has never seen: “I wish to Christ he does not deceive you as he has me”.

Presumably ending in accordance with the Griselda source material, the ballad concludes with the trouble-free formulaic stanza: “There was joy and yet more delight, / Sir Peder and Little Kirsten were wed”.

A quite different reaction was heard from Elena in the ballad about “Sune Folkesøn” when she declared that she could never forgive. A still more forceful demonstration of the limit to tolerance is provided by the raped sisters in the ballad about “Herr Ebbes Døtre” when they take revenge on their assailants. The ballad was recorded by Anne Krabbe, who locates the events in “Wiffuil bye” (Vivild Town) and “Wiffuild-march i Halherit” (the Vivild estates), and others: Vibeke Bild, for example, included by and large the same version in one of the folio manuscripts penned by her scribes. While Ebbe is away on a pilgrimage, we are told, his daughters are sought out and raped by two brothers. Ebbe returns home and learns of the assault, but he is reluctant to exact revenge, feeling that his pilgrimage will have been wasted if he now gets blood on his hands. The young women react robustly:

You shall not for our sake

don armour and draw sword,

we will avenge it ourselves,

if we are worthy of honour.

I shall Iche for woris skijld,

drage brijnie och suerd,

selff will wy det heffne,

Om wy er Ære værd.

The sisters kill their assailants in and by the church – which does not provide its usual protection. The ballad makes no comment on the consequences for Ebbe’s daughters, but it pities the slain brothers’ mother, for she is a victim of the negative side of revenge culture:

Home went Ebbe’s daughters twain,

once they had avenged the offence they suffered,

in sorrow Mrs Mettelille had to

lay her sons in the grave.

Hiem fourr Ebis døter tou,

der di haffde heffnet deris skade,

med sorig mone fru mete Lile,

koma hindis søner i graffue.

Women Informants of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Ballads

The early Icelandic ballad tradition, recorded in manuscripts from the mid-seventeenth century to the mid-eighteenth century, includes the ballad about “Herr Ebbes Døtre”; with its revenge motif and restoration of the balance of power between two families, it recalls the uncompromising family-conscious characters of the saga literature.

In the second half of the nineteenth century we find the ballad in the repertoire of an old niðurseta (female pauper given food and lodging), Gunnhildur Jónsdóttir (1787-1866). Throughout her story of Sir Ebbe’s daughters, of which she recalls individual verses with connecting prose, we experience the poor and oppressed people’s fear of anger and punishment from the ‘great and the good’. In her version, the reaction of the young women who have been raped is one of fear: they kill their assailant when he again tries to attack them outside the church, and when his brother turns up they kill him too. Revenge is changed into self-defence:

“Peter went into the church and there drank wine, but his brother met the Ebbe-daughters outside and would seize them, but they prevailed and would kill him.”

The aristocracy had a particular lyrical ballad genre, but the common people often changed a folk ballad’s plot-driving refrain into a lyrical refrain. The older version of the ballad about “Herr Ebbes Døtre” has a refrain stating: “So lovely on the ground” (Danish) and “Where noble swains ride forth” (Icelandic); in the version made by the Icelandic peasantry, this is expressed as: “Dew falls of the fair forest oaks” (translated).

Gunnhildur Jónsdóttir has incorporated the truth about herself and her own life into her version. She has no interest in chivalrous codes of honour that say attack must be avenged by counterattack. But she is familiar with atrocities that trigger defence mechanisms, and she is particularly familiar with fear of the consequences of actively resisting violation. When Ebbe finds out that his daughters have slain the brothers – and they are the king’s men – he fears the king’s wrath: “Up rose Ebbe / and spoke thus: Fortunate is the one alive, / who no child doth have / Dew falls of the fair forest oaks.”

Gunnhildur Jónsdóttir adds a fairytale ending, which demonstrates what happens when a text wanders from one milieu to another. In order to overcome her anxiety about the fate of Ebbe’s daughters, she has to add the most powerful conclusion she can: a good marriage is the best outcome for young women who have, whether they have brought it upon themselves or not, ‘got into trouble’:

“But when the King became privy to this news, he was gladdened that the brothers had been slain, and he thought so well of the Ebbe-daughters, that he gave them in marriage to each her nobleman.”

The king is all-controlling and all-powerful in this re-creation of an old ballad, which the informant starts off with a fairytale formula: once upon a time there was a king.

Gunnhildur Jónsdóttir was one of the best informants for, among others, Brynjólfur Jónsson, the young farmer’s son at Minni Núpur where she was on pauper’s assistance. In a letter dated 1 February 1863, the then twenty-four-year-old Brynjólfur Jónsson writes that he has soon filled a third book with ballad texts, most of which were told to him by Gunnhildur Jónsdóttir, but that he was worried about her and thus also about his work:

“[…] she fell ill before Christmas, and I was afraid she might lie down and die, I therefore made haste to take narration from her.”

Gunnhildur Jónsdóttir did not in fact die until a few years later; one of the ballads she lived to narrate was “Margrétar kvæði” (Margrét’s Ballad), which was probably originally a Faroese ballad. It is a cruel ballad dealing with rape, incest, and violence, but Gunnhildur Jónsdóttir has her own version: “Margrét was made pregnant by her father”. Her father thereafter attempts to burn her on a pyre, but her brother saves her; one of the women who come to take care of the sons she gives birth to in the flames also takes care of Margrét: “Elenborg, she took Margrét with her”.

Old and impoverished Gunnhildur Jónsdóttir knows how important it is that someone looks after the weak.

Ballad collection in the late 1800s was in a race against time and development if the tradition, which was still active among the singing and narrating but not writing peasants, was to be saved. Brynjólfur Jónsson’s zeal was shared by the Danish collector of folklore, schoolmaster Evald Tang Kristensen (1843-1929). In Minder og Oplevelser (four volumes, 1923-27; Memories and Experiences), he writes:

“I now returned to Hygum and visited the old woman Kristence Kristensdatter, whom I had called on a few days earlier. She was born on New Year’s Day itself and was now 93 years old. Being so extremely old, her daughter had to help her constantly, for her memory would not assist, and thus it was well that the daughter knew most of what her mother had sung and narrated, and in this way could still be of help to us. I wrote down the 14 old ballads and 5 folktales. She had lived out on Harboøre but had to move away when, on the night of a storm, the water flowed into the house and rose above their table. They climbed up into the loft, and there they sat for two-and-a-half days, until a boat came and rescued them. Thus she sat and told me of strange occurrences from her life. As can be imagined, I could not be finished with her in a jiffy.”

At the time of giving her information, Kristence Kristensdatter (born 1796) was a rentier in Hygum; the presence of her daughter, Maren Olesdatter, was of additional benefit when it came to notating the tunes, and Tang Kristensen goes on: “There in Hygum I wrote down a good many melodies, which Kristence’s daughter sang for me.”

It was on this occasion that Evald Tang Kristensen recorded Kristence Kristensdatter’s version of the ballad about “Hustru og Mands Moder” (Wife and Mother-in-Law). The ballad is related to “Hustru og Slegfred”, and had been recorded by Christence Juul approximately 270 years earlier. The story of “Hustru og Mands Moder” differs on a few points from its old kindred ballad: a spell is cast on a pregnant woman, not by her husband’s jealous mistress but by his mother. After an agonising eight-year pregnancy, she goes home:

They drive so softly across the heath,

awaken no man and anger no man.

They drive so softly across the bridge,

awaken no man, cause no alarm.

In this version by Kristence Kristensdatter, the woman is received by her father and we hear nothing about the mother. Little Kirsten dies having given birth to two sons. They have been eight years in the womb and are ready to take their affairs in hand:

The first he was so wise a man,

for he would rule his father’s land.

Seven barrels sulphur and five barrels tar;

and that I will give to my mother-in-law.

And so the wicked mother-in-law is to be burnt as punishment for the misery she has wrought.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries another ballad about difficult childbirth, “Redselille og Medelvold”, was sung, like “Hustru og Mands Moder”, by Danish countryfolk, men and women alike. Kristence Kristensdatter and her four singing daughters also knew the ballad about “Redselille”, telling the story of how Rosenelle (the same as Roselille) is turned out of her home while pregnant. She and her sweetheart flee to “Rosenslund” (rose grove), where she goes into labour. Her sweetheart fetches water for her, and at the spring he hears a nightingale: “In the grove there sings a nightingale thus: / that the children are in life but the mother is dead.” For the impoverished father it would be a disaster to be left with motherless children, so he responds: “Alas, nightingale, nightingale, sing not so, / say: the mother is in life, but the children are dead.” The infants die too, and he never recovers from his grief: “And he rode ever so far out into the land, / for his young sons stood at his side.”

This concluding stanza is unique to Kristence Kristensdatter and her daughters, and must be the old rentier’s addition. The informant who spends her life with her songs will also reflect that life in the songs.

The ballads about “Redselille og Medelvold” and “Hustru og Mands Moder” are found in both the Norwegian and Swedish seventeenth- and eighteenth-century tradition. A version of “Hustru og Mands Moder” was narrated by the Swedish ballad-singer Greta Naterberg, born 1772 in Östergötland.

Greta Naterberg’s parents were Per Callerman, a cavalryman, and Kerstin Lagesdotter. In 1794 she went into service at the Västerby estate and in 1800 she married Peter Hansson, a soldier, in Röby. He later joined the Household Grenadiers in Naterstad, in the parish of Slaka, and took the surname Naterberg. Greta Naterberg, who bore a number of children during their marriage, died in 1818.

A few years before her death, her recorder, L. F. Rääf, wrote about her and her large repertoire of ballads: “Of her ballads, almost none were learnt after her 20-25th year. She has the finest memory and still knows snatches of quite a lot of ballads, which she remembers when they are mentioned […]. She is of a spry and cheerful disposition – complains that her voice is not as clear as it was in her young days, and that her chest grows heavy and is often poorly, especially in winter.”

Her ballads, a large proportion of which she had learnt from her mother, were not passed on to her children, according to L.F. Rääf: “She is now the mother of several children – those of them I know seem utterly to lack their mother’s sense of song.”

The cheerful young woman’s version of the childbirth ballad has a happy ending: Little Kirsten survives, having given birth to a boy and a girl. First, however, she has to endure a painful nine-year pregnancy, bewitched by her mother-in-law, and in the end she decides to return home to her mother:

Little Kirsten spoke thus to Sir Peder:

While the linden tree bears leaves so green,

Take me home to my mother’s farm,

And they rode, they rode off with her through the grove.

Liten Kerstin hon talte till Herr Peder så,

Medan linden bär löfven så gröna,

Och hämta mig hem till min moders gård,

De redo, de redo bort igenom lunden med henne.

The informant expresses Peder’s affection for Little Kirsten in the lines:

And listen, Little Kirsten, to what I say to you:

If you are fit to ride, then I will walk with you.

Och hör du, liten Kerstin, hvad jag dig säga må,

Och orkar du rida, sjelf vill jag med dig gå.

His love is reciprocated, as we learn from the stanzas:

And my mother dear, make up my bed,

O dear Sir Peder, help me into it.

Little Kirsten sat upon the gilded chair

Sir Peder removed her stockings and shoes.

Och kära min moder J bädda opp min säng,

Å käre Herr Peder du hjelp mig i den.

Liten Kerstin satte sig på förgyllande stol

Herr Peder drog af henne strumpor och skor.

Even ballads that depict the lives of ordinary people in the most realistic manner are sprinkled with gold, gilt, and silk from the world of fairytale. The final words are Greta Naterberg’s own, and they disclose her uncomplicated, positive disposition:

And the son could run errands in the town,

and the daughter could sew the red silk.

Och sånen han kunde gå ärende i by,

Och Dottren hon kunde röda silket sy.

The gilded language of fairytale was applied everywhere:

Kari arrived in Heaven both tired and sorrowful,

the virgin [Mary] offered her the red golden chair.

Kari ho kom seg te himmerik både trøytt å mo

jomfru tukka te rødegullstol.

Norwegian sisters from Selgjord parish in the province of Telemarken, Ingebjør Kivle and Aaste Haugjen, narrated this account in 1874, describing Kari’s reception into heaven after she has been killed by two rapists. The line would seem to be peculiar to the sisters’ version of the ballad about “Torgjusdøtrane” (the Daughters of Torgjus). When the collector Sophus Bugge showed it to their sister-in-law Alet Aaseim, who was also from Selgjord in Telemarken, she said that she had heard something similar. She refused to include a motif from a different version, which does indeed have quite a different attitude to the consequences of the crime, just as there is a large gulf between the modest Kari described by her sisters-in-law and her own Proud Kari. Alet Aaseim uses six lines to describe how Kari adorns herself:

Proud Kari was wearing a red cape,

it was as if gold was strewn on the floor.

Proud Kari stood and clad her foot

in silk stockings and silver-buckled shoe.

– and finally:

Proud Kari stood and combed her hair

then tied it with a silken ribbon.

Stolt Kari ho ha på kåpa rø

de var lisso gulle på jori mon strø.

Stolt Kari ho sto å skodde sin fot

mæ silkjesokker å syllspente sko.

Stolt Kari ho sto å kjemde mæ kamm

so slengde ho ikring eit silkjeband.

She then rides off into the forest, where she encounters two violent thugs who give her a choice: going along with them – or death. She proudly replies: “I will not take up with two robbers / I would rather lose my life on the wild heath.”

They kill her, which is where most Norwegian versions of the ballad end, but Alet Aaseim continues in prose: “They travelled far, and they wanted to sell her clothes and her gold. Then they arrived at her father’s, but he recognised the clothes.”

All unsuspecting, they arrogantly ask for something to drink: “Draw me a pot of mead / and they asked loudly: let it be sweet.” They drank, Alet Aaseim continues in prose, until their stockings were soaked in blood, for her father had put poison in the drink.

Alet Aaseim’s revenge ballad differs strikingly from the conciliatory legend-like version told by her sisters-in-law: “Kari she knelt down on her bare knees / My dear, my Lord, forgive the robbers.”

To include the motif of Kari’s admission into heaven would be an inconsistency of epic proportions, such as rarely occurs in the narratives of popular ballad singers.

The Danish, Icelandic, Swedish, and Norwegian peasant ballad tradition is often coloured by the informant’s own circumstances in life, and it is firmly linked to the narrative situation, whether the ballad is sung as a pastime or told in song and prose for family, housemates, and co-workers. The Faroese ballad tradition, right up to the present day, has retained an element that is less pronounced in the other Nordic informants: the ballad as accompaniment to dance, and thus even more of a communal activity.

Rita Pedersen

Dance with One Another, as fairly as you can.

On the Faroese Ballads

The Faroese ballad form is a synthesis of words, melody, and dance. In the ring dance, the song is led by a single singer, and the rest of the dancers in the ring join in, as best they can, and everyone sings the refrain after each verse. The lead singers have usually been men, even though it is said that women, too, have led the singing of long ballads. The general view has been that women led the singing in order to warm up, as it were, for the dancing – they sang before the dance really got going – and that women mainly sang the shorter ballads.

That the Faroese ballad has an important function as an accompaniment to dance is corroborated by the fact that the great majority of refrains either mention or call for dance. The one quoted here (“Mirmants kvæði”; Song of Mirmant) is used, with a few variations, in several ballads.

The oldest and original Faroese ballads are in the Faroese language and are called kvæði, as distinct from the visa primarily associated with the Danish ballads (viser) which came to the Faroe Islands with the first ballad books, published by Anders Sørensen Vedel (1st edition 1591) and Peder Pedersen Syv (1st edition 1695). More Danish and Norwegian ballads came later, through the works of parson-poet Petter Dass (1647-1708). Alongside the Danish and Norwegian ballads, Faroese kempuvísur (heroic ballads) have been composed for dancing right up to the present day. A special Faroese genre is the táttur. The word táttur has two meanings: a section (chapter) of a ballad, or a more recent independent genre covering lampoons and satiric ballads.

Collection of the ballad tradition in the Faroe Islands began in the late 1700s; the anthology Føroya kvæði (Faroese Ballads; also known as Corpus carminum Færoensium) represents ballads collected in the period between 1770 and 1870. The source reference specifies 146 informants – of whom one in five were women, each with a repertoire ranging from one to six ballads – sixty-four versions of tales and fifty-two different ballads.

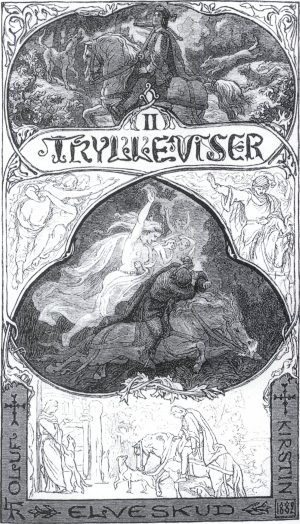

The female informants follow the distribution of ballad genres as a whole in Corpus Carminum Færoensium. Heroic ballads, which are the main Faroese ballad genre, are in the majority, followed by ballads of chivalry, ballads of magic, and legendary ballads.

At first, women taking part in the Faroese collection were exclusively informants. In Vágur, on the island of Suðuroy, a collector found two excellent informants in Birita Jacobsdatter á Mýri (1805-1874) and Anna Sofie Iversdatter á Skála (1822-1863); in the period from 1847 to 1848, they narrated six and four ballads respectively.

In Birita’s ballad about “Mirmant”, the women fight over the man, using both cunning and deceit, but eroticism and noble motifs carry the day.

In Birita á Mýri’s version of “Magnus kongur í Noregi” (Magnus King of Norway) or “Margretu kvæði” (Ballad of Margaret), the king’s daughter, Margaret, is sent to a convent, but one day on the way home to visit her father she encounters a man who rapes her; he turns out to be her brother:

He ripped off her dress,

then her silk shift,

until he had inflicted upon her

the sinful work of need.

Hann reiv av henni stakkin

so hennar silkiserk,

til hann hevði vunnið henni

tað syndar neyðis verk

Her father visits her and discovers that she is pregnant; when she refuses to reveal the identity of the baby’s father, her own father sets fire to the convent. Her brother hastens to the spot and tries to put out the flames, but they both die.

“Margretu kvæði” is specifically Faroese, and it is thought to have travelled to Iceland from the Faroe Islands. It was particularly popular with women. Of the in-all five versions, three were narrated by women and one had been learnt by the male informant from his maternal grandmother. It was also mostly women who sang this ballad in the dance.

Another of Birita á Mýri’s ballads, “Pálnir Búgvason”, tells of abduction and revenge. Pálnir abducts a woman who is engaged to be married; she protests and warns her abductor of the following:

Listen, Pálnir Búgvason,

you must not meet me in the grove,

should farmer Niklas hear of it,

he will strike you down like a dog.

I fear not Niklas,

his hawk nor hound,

maid, follow me

through the green grove.

Hoyr tú, Pálnir Búgvason,

tú kom ikke á mín fund,

frættir tað bóndin Niklas,

hann høggur teg sum ein hund.

Eg ræðdist ei bóndan Niklas,

ei hans heyk og hund,

jomfrúin, tú skal fylgja mær

ígjøgnum grøna lund.

She then obeys her abductor and future husband and the rules of marriage, but on their wedding night Pálnir dies at the hand of her father. The newly-wed couple had managed, however, to beget twin sons, who later avenge their father – he had instructed their mother to make sure that they did so.

In this ballad, the woman follows the man even though he has taken her by force. She offers resistance at the moment of violation but thereafter, for her part, she sees the relationship as fixed. Revenge is something that men – her sons – must undertake. In “Margretu kvæði” and “Pálnir Búgvason” men use deceit and violence to get the woman they want; indeed, Birita á Mýri’s repertoire in general deals with evil versus good in the relationship between man and woman.

A group of women – among them Birita, who was clairvoyant – once passed by a hillock inhabited by hulderfolk. One of the women got something in her eye. Birita threatened the hulder and asked the women to leave. When the others were home safe and sound, Birita called out: Kiss me! For she had seen one of the hulders throwing ash out of the hillock.

In three of her four ballads, Anna Sofie Iversdatter á Skála also focuses on the man-woman relationship, particularly on the woman’s situation during engagement and wedding. “Greivin av Jansalín” (the Count of Jansalín) tells of the Count who goes out into the world to test his manhood. Once this Count has slain an adversary, Sir Ivar, a maiden expresses her desire for him, but he punishes her for volunteering her services – he kills her:

She sees a hero so famed

ride forth on the field of battle.

“Such a man would I have chosen,

had I the choice to make.”

He held aloft his right hand

struck her across the mouth,

blood poured down her breast,

as witnessed by many men.

Hon sær ein so frægan kappa

á leikvøllinum ríða:

“Tílíkan vildi eg kosið mær,

hevði tað staðið til min”.

Hann hevði upp sína høgru hond,

gav henni høgg á tenn,

blóðið dreiv í barmin niður,

sóu tað mangir menn.

The Count later gets the better of a king, who offers him his betrothed in exchange for his life. In return, the king would get the Count’s sister:

“If you give me your betrothed,

maiden Solitu,

I will give you my fair sister,

the young maiden Gunhild.”

“Gevur tú mær jomfrú Solitu,

festarmoynna tína,

eg gevi tær ungu Gunnhildu moy,

so væna systur mína.”

This transaction is negotiated without the two women taking part in the ballad. They are perceived as the men’s property, and if a woman should take an initiative she is punished without mercy. The women in Anna Sofie Iversdatter’s ballads are brave. They would like to have a husband, but marriage should be contracted in an honourable fashion. Her ballad about the Count who trades his sister, as if she were an object, for the king’s betrothed, can be read as Anna Sofie Iversdatter’s protest against male denigration of women.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the first women started recording ballads: Kristjane Schröder (1802-1873) narrated three and wrote down three of her own.

Four of Kristjane Schröder’s ballads deal with betrothal and marriage. “Kongur og jomfrú” (King and Maiden) is a short ballad, partly in Danish, about a king who sends gifts to a maiden. One of these gifts is a nightingale; the bird discloses that, in return for the gifts, the king wants her as his mistress:

The maiden speaks to the nightingale:

“What does the Lord wish in return for his gifts?”

“In return for his gifts my lord wishes,

To speak with you in secret love.”

The maiden then sends the gifts back.

Kristjane Schröder’s version of this ballad is open and straightforward. The battle between a bad and a good outcome for women in her repertoire translates into the women’s desire to retain their integrity and protect themselves against the men’s dishonest and egoistic intentions. The composition of repertoires will, in one way or another, shed light on the informants’ attitudes and feelings. The Faroese informants mentioned here have been particularly concerned about women’s situation when subjected to brutality and humiliation, and when their status is in peril.

Malan Simonsen

Finis the End of these Songs

Throughout its entire 400-year-long tradition, the Nordic ballad has been associated with dance: “A maiden steps out in dance”, “There is dancing in the meadows”, and “For dance it flows out in the grove” are just a few of the many first-lines and refrains to mention dance.

Ballads outside the Faroe Islands were not linked as specifically to dance, but informants of the later ballad tradition could nonetheless occasionally report that people danced to their songs. In 1815, L. F. Rääf wrote that, according to the Swedish informant Greta Naterberg, young people in her day would gather on Slaka hill “where she sings her games for them so that they dance and play late into the night”.

A slim mid-seventeenth-century Danish ballad manuscript owned by Karen Christensdatter, of whom no more is known than her name, provides a direct indication that the older ballad tradition was not collected by the aristocracy simply on grounds of literary and archival interest:

Take the ballad in your hands,

and sing it lustily and plain,

so everyone can hear it clearly.

Tag visen nu J Hænde,

Och siung den lystig oc klar,

Att hver kan høre dig Aabenbar.

This note, written below the first entry in the ballad book, shows that we are dealing with a living tradition that was sung and danced to the best of the individual’s ability, as stated on the last page:

Finis the End of these songs,

the one who cannot dance, must walk in time.

Finis Ende paa disse sange,

hvo ey kand dantze maa efttergange.

Rita Pedersen

Translated by Gaye Kynoch