“Has the young lady read Ibsen?” In this way, as the anecdote goes, a man from the cultivated social stratum of the 1880s could begin a conversation with a young woman. Whether it is true or not, the phrase reveals the great impact of the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. The female writers of the period were also attracted, especially to his idealism. To this must be added a psychological factor. Thanks to his reputation, Ibsen, who was initially a champion of women’s emancipation, certainly legitimised the female authors’ feminist tendencies. Like their male colleagues, many of them also found their themes and ideas in his writings. To be sure, this was a period in which, as Klara Johanson has aptly put it, authors “practised a kind of communism as far as thoughts and ideals were concerned”.

However, in historical hindsight the references to Ibsen have come to be seen as plagiarism, as an expression of the women’s lack of literary originality. But this is a simplified view, since Ibsen did not always go unchallenged. On the contrary, several of the women of the Modern Breakthrough felt provoked to correct or revise Ibsen’s original text, and time after time his portraits of women turn up in their plays and short stories, but rewritten on the basis of a different horizon of understanding. Two obvious examples from 1882 of such a female, partly subversive dialogue with Ibsen are Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler’s (1849-92) short story “Tvifvel” (Doubt), which is a reply to Ibsen’s Brand (1866; Eng. tr. Brand, A Dramatic Poem), and Alfhild Agrell’s (1849-1923) play Räddad (Saved), which is a revised version of Ibsen’s Et dukkehjem (1879; Eng. tr. A Doll’s House).

These texts clearly show how Ibsen’s portrayal of women served as a challenge, a set piece that had to be tested and partly destroyed in order for the two female authors to arrive at a more credible story. The overall common denominator of their replies is the veil of despair that is thrown over the young woman’s situation. The fathers are absent, dead; the mothers likewise, either in a metaphorical or a literal sense. If there is an older woman in the immediate vicinity, she lets the young woman down. All that is left is a life-threatening vulnerability and loneliness in the stifling feeling that, in an existential sense, it is impossible for a woman to be free. Therefore, it would have been inconceivable for the female protagonist in “Tvifvel” or in Räddad to imitate Doctor Stockmann’s famous dictum in Ibsen’s En folkefjende (1882; Eng. tr. An Enemy of the People) in this way: ‘The strongest woman in the world is she who stands most alone’.

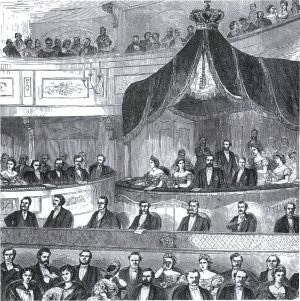

That Räddad (1882; Saved) was regarded as topical, as a text that really appealed to the audience, is documented by the fact that Kungliga Dramatiska Teatern (The Royal Theatre) in Stockholm put on the play no fewer than twenty-six times during the period from 1882 to 1884. In comparison, Strindberg’s plays, with the exception of Lycko-Pers resa (1882; Lucky Pehr’s Journey; Eng. tr. Lucky Pehr), were seldom performed more than ten times.

At a first glance, however, it is an astounding fact that neither Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler nor Alfhild Agrell had any intention of hiding their sources of inspiration. On the contrary, the references to their sources are completely obvious and not at all dressed in the cautious attire of the palimpsest. Rather, their strategy appears to have been to deliberately keep Ibsen’s texts in the reader’s/audience’s mind, so that, by the effect of contrast, their own texts would stand out so much more poignantly. Therefore, the explanation for why they base themselves as closely on the Norwegian plays as they do should not be sought in any lack of ideas of their own, but rather in a well thought-out strategy to make their own voices heard and offer their own version of femininity, from a female perspective.

Through the dialogue with Ibsen, Alfhild Agrell and Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler placed themselves at the centre of the period’s ideological debate. They were friends and shared a pessimistic tone as well as – conversely – optimistic zeal and great success. As two of the most recognised female authors of the Swedish Modern Breakthrough, they reached far beyond the borders of their home country. Their works were translated into other Nordic languages, into German and English, and even, in Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler’s case, into both Russian and Italian. Some of their plays were also performed on international stages.

They first met in the early 1880s, and over the next few years they saw each other if not on a daily basis then remarkably often. Together they went to the theatre and to lectures, they read aloud and criticised each other’s works, and they met with their male colleagues. A manifestation of their leading position at this time is their election to ‘Publicistklubben’ (The Publicists’ Club) – previously an exclusively male forum – to which they were admitted in 1885 as two of the first three women. The third was Sophie Adlersparre, whom the members of the club considered to “belong to the more conservative camp”.

In addition to Ibsen, they thus had several points in common and, as Alfhild Agrell puts it, their writing projects were directed at the future: “You have to invest your interest, your life, your blood in the present in order to be able to work for the time that is to come; and there can be no doubt that without enthusiasts, without those who believe too much, who desire everything, who see stars where others see only spots, you won’t get anywhere.”

Homeless

Alfhild Agrell reached the peak of her career as an author around the middle of the 1880s. In Stockholm she was then the female playwright in fashion, and in Copenhagen she met with an appreciative Georg Brandes. For its part, the newspaper Svenska Dagbladet predicted a more certain future for her as an author than for Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler, despite the fact that both had “their fingers in the pie of world improvement”, as it was ironically formulated.

“The only thing that I envy Mrs Agrell is actually Brandes’s portrait of her. I regard it as a medal, the one that is awarded for literary merit; and I shall have to wait”, Victoria Benedictsson writes in Stora boken (1886; The Big Book).

Subsequently, however, Alfhild Agrell was to experience a number of things that embittered her life, and over the years she entered a vicious circle of homelessness and isolation. Her divorce in 1895 resulted in veritable ‘Wanderjahre’, homelessness, and a blurred social position. ‘The love of her life’ never materialised, and neither did ‘the work of her life’. The novel Guds drömmare (1904; God’s Dreamers), which she herself thought of as her chief literary venture, was not received as she had hoped. A further strain was her pecuniary difficulties and her weak health due to a lung disease. Gradually, her attitude to her own role as an author also became more and more ambiguous, and her decision to burn her diaries and letters may be seen as a manifestation of this doubt.

Despite lofty protestations of indifference and other Stoical virtues, Alfhild Agrell came, during the later part of her life, to incarnate – far removed from publicity and from the salons of the 1880s – the Breakthrough topos of solitude. But the tragedy of her life does not speak to the imagination, since with her roots in the period of the Modern Breakthrough she outlived herself. This may have contributed to the fact that, in the eyes of posterity, she has been overshadowed by, for example, Victoria Benedictsson and Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler.

In a letter of 18 March 1923, Klara Johanson writes to Elin Wägner:

“What you wrote about Alfhild Agrell made me happy: that she used to spend Christmas with you, for ever since I saw her stealing along the rows of houses in Copenhagen in 1919, I have been tormented by the thought of her solitude and forlornness and rootlessness.”

In contrast to this stands the stir Alfhild Agrell caused in the early 1880s. After she had her one-act play Hvarför? (Why?) performed at the prestigious Kungliga Dramatiska Teatern (The Royal Theatre) in Stockholm in 1881, the ice was broken and she was increasingly mentioned as a writer of travel accounts, descriptions of the lives of common people, and problem-oriented plays. As a portrayer of the lives of common people she was one of the best of her generation and was benevolently recognised as such by the press. Her stories are nearly always situated in her native province of Norrland, and among other things she introduced the Norrland fishing hamlet as a motif in Swedish literature. The tempo is quick, and the metaphorical language conveys with attentive detail the imagination of the country people. What emerges are swift, impressionistic portraits with a stamp of authenticity. Contributing to this authenticity are the dialectal features and the assurance with which the narrator moves in the world she wants to capture.

Just as in her other texts, motherhood – regarded as both an option and a problem in a woman’s life – is a central theme in her descriptions of the lives of common people. As in Strindberg and Gustaf af Geijerstam, motherhood is often presented as something valuable in itself, an enhancement of the feeling of life and an ethical power that can normalise the relationship between the spouses in a previously disharmonious marriage. At other times, it is problematised through portrayals of cold, barrenly ‘sensible’ mothers who have internalised a patriarchal norm system and are playing its game. They mould their daughters into defensive, shadowy figures and their sons into the opposite. Thus, in Alfhild Agrell’s fiction, both men and women are the victims of a warped view of gender roles.

Despite her high regard for motherhood, Ellen Key’s mythological view of motherliness nevertheless seemed controversial to Alfhild Agrell. In a long 1896 letter to Ellen Key, she writes among other things:

“Motherliness is the supreme, is the bloom on the tree of humanity, but the tree must be allowed to grow for the flower to be able to open […]. Motherliness must be obtained through humanity. Only when we women have tested our strength, have enjoyed all the things life can give us, only then can your elite group emerge and ensure the rebirth of the species, that group from which I, at any rate, expect the greatest happiness for humanity.”

These lines make it clear that Ellen Key was ahead of her time. Before her vision could be realised, the lack of equality between the sexes had to come to an end, the woman had to gain existential independence, and the man had to become conscious of his responsibility as a father.

The Art of Staging

Alfhild Agrell attracted most attention, however, as a playwright. Along with Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler in particular, she made the 1880s the decade in which women really conquered the stage in Sweden. In the preceding period, the female playwrights’ contributions had essentially been limited to a few historical plays, comedies, and translations. The female authors of the Modern Breakthrough also cultivated the comedy, but they were especially keen on the genre of the ‘thesis play’. They were, of course, aware that, in view of the public character of the theatre, the drama was a more dangerous genre than, for example, the novel or the short story. Nevertheless they chose, time and again, to speak out and argue from the stage. A reason for this may have been their awareness of the great impact of the theatre as a medium, since regular visits to the theatre were a normal part of the social life of the period’s middle and upper classes. Moreover, the Kungliga Dramatiska Teatern boasted several talented actresses, among others Olga Björkegren, Ellen Hartman, and Thecla Åhlander, who had been captivated by the ideas of the Modern Breakthrough and thus could do justice to the new plays that dealt with women’s issues. In Gustaf Fredriksson, Emil Hillberg, and Ferdinand Thegerström, for example, they had equally capable male actors to play opposite them.

In her plays, Alfhild Agrell does not one-sidedly focus on the period’s marriage debate with its demand for legal and economic equality between husband and wife. She just as often shows a passionate interest in the unmarried and single mother, whom she stands up for in a manner that is remarkably dauntless for the time; in this context the sexual double standards are one of her primary targets. Already in Räddad (Saved) she touches upon this issue, but in Dömd (1884; Condemned) she makes her position plain. The play is a singular contribution to the ‘morality controversy’ in so far as it does not theorise about equal sexual abstinence or freedom for the woman and the man before marriage. When Dömd begins, the woman has already lived out her love and her desire, given birth to a son, and been deserted by the man. Both she and her child are considered outcasts, whereas the father is let off the hook. The question that the play directs to the viewer is: can it be ethically defensible for a woman who has had a pre-marital relationship to be judged more severely, both by the law and ‘good taste’, than the man involved? Or as Alfhild Agrell brilliantly puts it: is it more offensive for the woman “to love and believe” (that is, in the promises made) than for the man “to love and deceive”?

In a line from Dömd (1884; Condemned), Director Hillner says to the mother:

“I have a thousand times more regard for the woman who has given herself out of love than I have for you, who are selling your own flesh and blood out of venal calculation.”

In Ensam (1886; Alone), the main theme is to a certain extent the same as in Dömd – namely a questioning of the reasons why, to the man, every moral issue is an individual and private concern, whereas the woman’s “mistakes belong to the world”. Likewise, the focus is upon the limits of a mother’s obligations towards her child. The problem had already been raised by the Danish author J. P. Jacobsen in the short story “Fru Fønss” (1882; Mrs Fønss), where the woman is torn between the sweetheart of her youth and her responsibility as a parent. In Alfhild Agrell, this conflict is extended to the mother’s choice between dignity and truth on the one hand and compromise and conformity on the other.

Like Viola in Räddad, the heroines in both Dömd and Ensam are female versions of ‘the individualist’ and ‘the solitary person’, who were celebrated figures in the literature of the 1880s. They eventually end up as subjects of their own stories, but at the high cost of involuntary loneliness as well as social and sexual isolation. The play does not present sisterhood as a potential safety net. On the contrary, the older women in particular are portrayed as hypocritical opportunists, whereas a few of the male characters are able to see through the hypocrisy.

Common to all of Alfhild Agrell’s female protagonists is their fixation on a romantic dream of love and complete mutual understanding. No matter how intense their love is, the trials it endures before cooling down are correspondingly great. It is “the woman’s hard work to twirl the turntable of passion”, as it says in a short story from the collection Nordanfrån (From the North), since she has been socialised to focus narrowly on her private life, where the recognition of her worth is expected to come from the man. This complex of problems is the subtext in nearly all that Alfhild Agrell wrote, and it is explicitly thematised in a couple of short stories in the collection Hvad ingen ser (1885; What Nobody Sees).

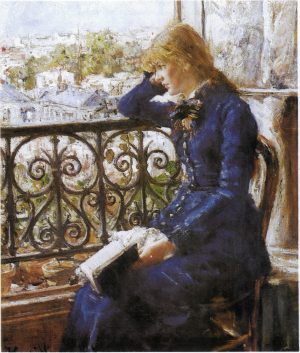

The motif in these short stories is the ball, and just as in similar stories by Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler, the young girl experiences this marriage market as a violation of her integrity. It is a forum that “idiotises” and that is exclusively meant to expose the woman as an attractive dancing doll. She quickly understands the ambiguity of the institution of the ball: on the surface exhilarating amusement, but at the core deadly earnestness in the pursuit of the man’s appraising, at best appreciative, glance. The all-important requirement for being able to lay claim to the latter is to command the art of self-staging.

In Alfhild Agrell as well as in Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler, the description of the determined gesture of the external attributes becomes an almost exact reproduction of women’s fashion in the 1880s. This was characterised, on the one hand, by tight-fitting dresses with a corset underneath, and, on the other, by the petite forms. The lack of interest in the functional aspect was further reflected in the fact that the shoes were too narrow, too short, and moreover identical, with no difference between the right and the left shoe. The heel was made as high as possible to make the foot seem small. Even gloves and muffs had to be too narrow in order to suggest dainty proportions.

The double message of the ball was thus already made visible in the female evening dress, which sent out contradictory signals by accentuating the woman’s figure in an erotically provocative manner while at the same time feigning doll-like prettiness and innocence: “Pure and yet passionate.” In the descriptions of the balls it is also stressed how the confirmation of the worth of the marriageable girl must come from someone other than herself, preferably from the man – or else from the older woman/the mother, who is assumed to have experienced the same deforming young-girl existence as her daughter, and who makes sure, with painful automaticity, that her own story repeats itself and that the power of the male gaze is upheld. To get an image of herself, in short story after short story the young girl chases a ‘pseudo-I’, a non-person, for whom the mirror in the private space replaces the man’s gaze in the public space. If, in enraged protest, she attempts to overstep the secluded and ambiguous tyranny of the ballroom, defeat lies ahead.

In Alfhild Agrell’s fiction, the ball’s double message continues into marriage, which takes on the character of a game in which the woman has to hide her feelings from the one she loves. “In a word, you should never know if you can command her [i.e., the wife] or not. This keeps love alive”, as it says in the play Ingrid. Therefore, the woman is never able to completely live out her potential for love, although she is not, any more than the man, a neutral being without urges. In accordance with the conviction of the Scottish doctor George Drysdale, Alfhild Agreel seems to believe that want of sex is equally harmful to men and women.

Adversity

To Alfhild Agrell, the aesthetic reorientation that became noticeable around 1886 meant that her plays were no longer performed at theatres in Sweden. The time of the indignant gender-role debate was passing. This does not mean, however, that she stopped writing drama. On the contrary, by 1887 she had completed a new whole-evening play entitled Vår! (Springtime). As the title indicates, the play represents a break with the description of misery in the earlier plays. Instead, it shows how a woman finds direction and meaning in her marriage by combining it with a paid job that gives her an identity beyond that of being her husband’s wife. In this way the play communicates a utopian vision of a female existence that is not split up but is complete. Although Vår! was accepted for production at the Kungliga Dramatiska Teatern, it was never performed.

“To live your life through your own power, to own yourself and each other, that is to own all of life’s splendour and fullness.”

From Alfhild Agrell’s play Vår! (1887; Spring!).

In response to the adversity of the late nineteenth century, Alfhild Agrell also took up a genre that was new to her, the humorous causerie. With an agile pen she uses the genre to smuggle in contraband and adopts the pen name and guise of the priceless ‘Lovisa Petterkvist’. The books became a success with readers and critics, and as a female writer of humorous causeries Alfhild Agrell is unique in her time. Therefore, all the critics naturally enough assumed that hiding behind the pseudonym was a man, or possibly a man and a woman in collaboration.

Alfhild Agrell wrote two volumes of causeries under the pseudonym ‘Lovisa Petterkvist’: I Stockholm (1892; In Stockholm) and Hemma in Jockmock (1896; Home in Jockmock).

The tone is darker in her last play, Ingrid. En döds kärlekssaga (Ingrid. A Dead Woman’s Love Story), which was finished by 1894 but was not printed until 1900 and to this day has never been performed. In Ingrid, there is a noticeable movement towards the psychological drama and away from the ‘thesis play’. This is combined with the airing of a more profound view of love and a Christian-inspired idea of sacrifice. A similar motif of suffering, with religious overtones, eventually returns in Guds drömmare (1904; God’s Dreamers), in which the woman, Margareta, is an ‘exceptional human being’, born to suffering and sacrifice.

This expansion of Eros to human Caritas reflects Alfhild Agrell’s own religious experiences. Therefore, both her own path and that of her female characters went from indignation to attempts at reconciliation as well as to mystical suffering. But the sacrifice is no easy victory. To win in this way, the woman has to accept total self-denial, and this turns out to be life-threatening. The subtitle of her play from 1894, “En döds kärlekssaga” (A Dead Woman’s Love Story), or to mention another example, Margareta’s premature death in Guds drömmare, thus essentially disavows, consciously or unconsciously on the author’s part, the whole project of suffering.

Alfhild Agrell’s fiction displays strong emotional overtones and an obsession with love and passion for the truth, which make it seem genuine. Notwithstanding her insufficient schooling, in her best moments she is able to produce sparkling lines and a witty and exciting dialogue that drives events and developments forward. At the same time she expresses herself in a less nuanced manner, and also more guardedly, than her male colleagues. By means of exaggeration, hyperbole, and understatement, the toned-down expression, she tried to make her voice heard using a strategy that is typical of whoever speaks or writes from an emotionally and/or intellectually inferior position. This ambivalence is also noticeable in the metaphors she employs about her fictive female character, who is both the submissive Cinderella and the aggressive rebel. Alfhild Agrell’s work, which is suspended between the discreet and the emphatic, accordingly seems to possess something of a Janus face: a reflection of, on the one hand, the ambivalence that characterised female existence in the nineteenth century and, on the other, her own complicated situation as a writing woman.

Klara Johanson on Alfhild Agrell in the journal Ord och Bild (Word and Picture) in 1905:

“The core of her play is the person who is upright, a fanatic adherent of truth, and above all courageous; who manages to carry loads of responsibility but not an ounce of injustice; and who is capable of sacrificing everything except her own inner dignity.”

An ‘Indignant Lady’

In their novels and short stories, both Alfhild Agrell and Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler often include elements of dialogue. In the lines of the female protagonists above all, pauses, expressions of hesitation, and broken sentences are used to mark insecurity, irresolution, and lack of control. These elements are combined with detailed descriptions of facial expression, posture, and gesture conveying the same metaphorical meaning. The two authors ultimately emerge as keen observers of the immediate and personally experienced reality.

However, in comparison with Agrell, Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler’s diction is more detached, and this places her in the period’s analytical and rationalist current. She also felt more secure in her role as a writing woman. Better schooling, health, economy, and a better social safety net provided her with a self-confidence that Alfhild Agrell lacked. Moreover, in her career as an author she enjoyed a totally different kind of support from her family and her closest circle of friends. It must be added, however, that, initially, her first husband wanted her to completely give up her ambitions to become an author.

“But all by herself sits Anne Charlotte Edgren, keenly observing. You get the impression that she is on the lookout for models, and people are a bit afraid of her. But when she speaks, what she says is wise and true.”

Gurli Linder on Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler in a memorial article in the newspaper Svenska Dagbladet, 8 November 1925.

Just like her friend, Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler obviously realised that the aesthetics of the Modern Breakthrough was gradually being undermined. Her reaction to this was strong, as appears from her private letters. Specifically, she suspected that the general attacks on the literature that submitted problems for debate, and the specific attacks on the “indignant ladies”, stemmed from jealousy on the part of the men. On 25 January 1888 Edgren Leffler wrote to her friend, the Danish educationalist and outdoorsman Adam Hauch:

“Presently, it is only the women who are successful in literature. Mrs Agrell, Ernst Ahlgren, and Mrs Edgren all enjoy greater popularity than any of the male authors. And therefore they are furious with us and with the whole women’s cause. This is the reason why I, who used to be called the leader of ‘Det unga Sverige’ (Young Sweden), now no longer belong to any camp. The old consider me too radical, and the young are jealous and take solace in insinuating every so often in the journals that our literary taste is still extremely undeveloped, since it is merely the women who sell.”

Meanwhile, Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler’s personal situation was changing, both publicly and privately, in a way that eventually made her less vulnerable than Alfhild Agrell. No more than her friend and colleague did she recoil from the social consequences of a divorce. But unlike her, she got married again, with the Italian mathematician and Duke of Cajanello, Pasquale del Pezzo. The couple settled in Naples, and it was her ambition to pursue an international career from there. Yet, her aspirations were never fulfilled. In 1892 she gave birth to her only, much longed-for child, a son. Tragically enough, she died only a few months later.

Femininity as Lack

Alfhild Agrell is above all the poet of female defeat. In a similar way, Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler writes about femininity as lack and loss, but she also attempts to reformulate it in terms of opportunity. The former aspect is predominant in her early collections of short stories, Ur lifvet I-II (1882-83; From Life), as exemplified in the stories about Arla and Aurore Bunge, respectively. Both women first turn up in “En bal i societeten” (A Society Ball), the opening short story in the first of the two collections. Here as elsewhere, Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler displays her skill at close-up descriptions, detailing with expert knowledge and lucidity the upper-class milieu and the determined body language of the dresses. As was the case for Alfhild Agrell’s young girls, so the débutante ball also becomes an embarrassing event for Arla, an event at which not even her cynical father – a newly appointed member of cabinet – hesitates to exploit his daughter. Male sexuality is confronted with girlish innocence, and Arla’s romantic dream of love is shattered.

“The subject matter is so loathsome that it grieves me that it has been picked up by a woman’s hand […]. The only excuse is that the author has wanted to show how a woman, through a contrived and empty life, can fall victim to her own suddenly awakening carnal nature.”

Sophie Adlersparre in a letter of 1883 to Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler, a propos of “Aurore Bunge”.

In the second collection of short stories, Arla turns up again in “I krig med samhället” (At War with Society), now as the wife in a marriage of convenience. The narrative is shaped as a gradually progressing study of female disorientation, and the plot is to a certain extent inspired by Strindberg and his life with Siri von Essen. In the first phase, Arla conforms to her resigned mother’s conventional view of marriage; in the second phase, to her equally conventional husband’s expectations of the good wife; and in the third phase, to her lover’s maverick radicalism. Under his influence she abandons her marriage, but the break-up is not deeply rooted in her. Rather, it is an attempt to construct an artificial identity by uncritically embracing the new man’s views and ideology. To Arla, this becomes a confrontation between ‘I’ and ‘not-I’, a conflict between her genuine motherly feelings and an inauthentic demand for emancipation. Her love for her children prevails, and in this way the short story becomes yet another reply to Ibsen’s vision of Nora. If one reads both of the separate stories about Arla in one sitting, they form a brief novel about a breakdown, in which the woman’s encounter with passion leads to her fall.

Another version of the same motif is the story of Aurore Bunge, which is likewise told over two short stories. In “A Society Ball”, Aurore comes across as Arla’s self-assured contrast, a rich and fashionably staged coquette. This gives her a high value on the market of the ball, and at the same time it illustrates the rigidity and petrification inherent in the woman’s status as an object. The sequel story, which carries Aurore Bunge’s name (in Ur lifvet, II), dramatises her attempt at breaking out of this objectification by way of a sexual experience. The description of an uncomplicated male sexuality is contrasted in this story with an ambiguous female sexuality. To Aurore, sexuality involves, on the one hand, a promise of liberation and happiness, and, on the other, a threat of chaos and loss. After her adventure she is one of the doomed. The female desire has broken down her identity as well as her sovereign self-image. Her old ‘I’, which she sees in the seclusion of the mirror, looks strange and insignificant; she cannot detect any new ‘I’ behind the reflected image.

On the ‘functional’ father-daughter relationship in “En bal i societeten” (1882; A Society Ball): “He was enough of a ladies’ man to realise that there was nonetheless something about her that would make her very celebrated. It had happened more than once that, thanks to a pretty daughter, an untitled cabinet minister had secured such a position in society that his background had been forgotten. ‘I am very satisfied with you’, the cabinet minister said after having finished his scrutiny, and patted the tiny shoulder that, slightly trembling, stuck out of the gown.”

In the stories about Arla and Aurore, the mothers are incapable of giving their daughters a positive perspective on life. Arla’s mother resigns herself to the norms of contemporary society; Aurore’s mother cooperates with the norms by closely observing her daughter’s moves and countermoves in the game of the marriage market. But the communication between mother and daughter is characterised by muteness and silence. The narcissism expressed in Aurore’s love of her own body as well as in her idealisation of her father can therefore, on a depth-psychological level, be interpreted as an insufficient reworking of an early fixation on a threatening mother imago.

A complicated mother-daughter relationship is in fact a motif that recurs time after time in Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler’s fiction. An unsympathetic, or at least weak, mother figure is also found in, for example, the short story “Tvifvel” (Doubt) as well as in a play from 1883 with the equivocal title Sanna kvinnor (Eng. tr. True Women), a play that ironically shows the self-destructive nature of ‘true femininity’.

Another example is the underlying criticism of the castrated and dictatorial mother that is woven into the novel En sommersaga I-II (1886; A Summer Tale), above all in the portrait of the deaf-mute Etty, who suffers from a lung disease. The description of Etty also becomes a condensed metaphor for female sexuality as something tabooed, sickly, and doomed.

“The woman has to be chaste, which is why it is immoral or at least highly distasteful to intimate that there is a physical side to her love.”

From a letter of 1886 by Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler to Adam Hauch.

Femininity as Opportunity

Above all, however, En sommarsaga examines the possibilities for a woman to combine the free life as an artist with the role as wife and mother. Just like Aurore Bunge, Ulla – the protagonist in the novel – initially comes across as an arrogant and self-confident young lady, who has adopted the male artist’s attitude and life style. But when she falls in love with the masculine and nature-loving school-teacher Falk, she winds up in a grey area and is in danger of losing her foothold.

“I have learned to compromise with regard to love; to take a bit rather than nothing at all. Usually, this is the way that only women love…”, says the consistently Norwegian-speaking character, Falk, in Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler’s novel En sommarsaga (1886; A Summer Tale).

To her, as to Aurore, sexuality is frightening, but the consequences for Ulla are not as devastating, since she has an occupation as an artist. This also complicates the situation, however, and there are no easy solutions at hand; Ulla is not able, in an unambiguous way, to choose the life as an artist above the role as a wife and mother, the principle of the individual above the principle of the family, or vice versa: “All I know is that I can never completely break away from you, nor can I ever completely live with you. I am doomed to eternal half-heartedness”, she writes from Rome to her husband. For his part, he is ready to make concessions and is assigned the role, which, in the traditional literary portrait of the artist, is filled by the wife. To be sure, Ulla’s ambivalence is not smoothed away by her husband’s willingness to compromise, but his readiness to meet her half-way opens up for a sexualising of their relationship, an opportunity for them to be able to respect each other as independent individuals, each with a story of their own.

The novel is innovative in its empathic description of Ulla’s maternity neurosis, an issue that had not been dealt with before by a Swedish female author. For some time after the child is born, the motherly happiness that Ulla had expected in fact fails to appear. On the other hand, ‘children at play’ is one of Ulla’s favourite motifs as an artist, and this seems to indicate that, to her, motherhood is both a desire and a threat. A similar ambivalence characterises Ulla’s attitude to contraception. In the spirit of neo-Malthusianism she questions herself about its legitimacy but does not offer an answer and therefore, like the author herself, ends up with an indecisive attitude on this incendiary issue.

However, the ambivalence that Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler so often associates with sexuality undergoes some modification in Kvinnlighet och erotik, II (1890; Eng. tr. Womanhood and Eroticism), which may be read as the sequel to an eponymous short story written seven years earlier and published in the collection Ur lifvet, III (From Life). In the short story, the young Alie is presented as an unconventional and pugnacious searcher, who nonetheless nourishes a romantic dream of love as life’s highest meaning and goal. But it is an illusion to feel loved and to believe that you can make the one you love happy. Alie senses that her female self-reflection, consciousness, and intellectualism are blocking a love of the kind that involves full mutual understanding. She therefore rejects Rikard’s half-hearted proposal, whereupon he marries Aagot “with the childlike eyes”, who is just as ignorant as she is charming. To him, the polarisation between the sexes is a prerequisite for erotic tension.

The Danish actress and author Johanne Luise Heiberg encouraged Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler to write a sequel to the story, in which Rikard “necessarily” had to be punished. This is what happens in Kvinnlighet och erotik, II, which takes place over a few summer months at the French Riviera, where Rikard declares his love and unconditional affection for Alie. However, she has fallen passionately in love with the Italian poet Andrea Serra, a scenario behind which one senses the author’s own love adventure with Pasquale del Pezzo. But Serra is the archetype of the passionate Latin lover, a common Don Juan with all the male-chauvinist views that one can think of and that he himself gladly airs in lines such as: “The woman wants and demands to be conquered – that is the nature of the woman.” Despite the fact that Alie is humiliated by Serra time after time, she loves him, and her metamorphosis is staggering. The only things that the Alie figure from the short story of 1883 appears to have in common with the same woman in 1888, when the novel was conceived, are her streak of unconventionality and her questioning of life-long marriage vows.

One way to understand this novel is to read it as a description of a desire without direction. This would explain Alie’s blindness to Serra’s foibles, since in that case the only thing she is seeking is narcissistic confirmation. Another possible approach is to follow the indications that point towards the influence of Ellen Key’s gospel of motherliness, which she first formulated in 1886. Serra’s conceitedness and tricks produce in Alie “something of the best and most profound in every woman’s love, something of motherliness. And her whole being is thrilled with the feeling of devotion and affection, which perhaps has deeper roots in the nature of the woman than mere sexual passion.” She hopes to be able to complement Serra with her ennobling influence upon him, and she thinks of him “the way a mother thinks of her child”. In other words, Alie abandons her vision of good mutual understanding between two mature persons in order to assume instead the role as mother to the demanding son/man.

The contemporary reception of Kvinnlighet och erotik, II was mixed. Among those entirely delighted were Ellen Key and the Swedish author and poet Verner von Heidenstam. The latter was “completely taken in: ‘this is pure renaissance’ – and that happens to be the highest praise he knows!”, as Ellen Key writes in 1890. The novel has also received great praise in retrospect and has been seen as the sign of a turning point in Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler’s writing career, away from the ‘problem literature’ of the 1880s. However, a couple of texts from her very last years speak against this, for example a draft from 1892 for a novel entitled “Trång horisont” (Narrow Horizon), which was published in Efterlämnade skrifter (1893; Posthumous Works). As it is available to us now, the story hardly gives evidence of any new orientation or bright confidence. On the contrary, we find here, for the last time, the whole inventory from the ‘problem literature’ of the early 1880s with its corrupt and drunken fathers, loyal wives and mothers-in-law, young daughters’ attempts at protest and liberation, as well as the capsized dream of realising both ‘the work of one’s life’ and ‘the love of one’s life’.

The saga play Sanningens vägar (1893; The Ways of Truth) describes an idealistic and uncompromising quest for truth, which, however, involves banishment from the idyllic paradise. In the words of the play: “Strife is truth, peace is a lie.”

Ultimately, one also senses in the private life of Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler a feeling of despair with regard to women’s opportunities, at least judging by a striking couple of lines from a letter of 2 June 1892. Here, she refers to her future child with these words:

“I’m saying ‘he’, seeing that we prefer to think of him as being of the male sex, simply because the chances are then better for him to become a productive person. Women are seldom so, and when they are, they are seldom happy.”

Translated by Pernille Harsting