“But within the circle of light I see the whole row of young, radiant faces, eager, intelligent, and with glowing enthusiasm. Happier people than the youth of the eighties have never existed. That was the time of the big general principles; all doors stood wide open to us. And everything that is needed to make life full and complete and worth living for the young – discussing principles and streaming out through the open doors to take possession of all the freedom of spirit and splendour that was waiting out there – this exactly was our duty, our calling, our mission.” With these euphoric words, the circa twenty-year-old Anna Bugge, later the life companion of the economist Knut Wicksell, captures her impressions of a meeting of the Norwegian female students’ association ‘Skuld’, in the middle of the 1880s. When, in the same decade, women for the first time on a broad front entered onto the public scene in Sweden, they cherished similar hopes of self-fulfilment, expansion, and protest against an outdated view of women.

Between 1879 and 1889, no fewer than 148 women made their debut as authors in the Swedish and Finnish-Swedish language area, the majority of whom were literary critics and writers of articles. Their voices, which now blended into the debate, became a manifestation of the fact that the female perspective could no longer be ignored. Moreover, they were able to publish their articles and other written contributions, which to a great extent addressed the era’s questions of marriage and education, in such specifically women’s journals as Tidskrift för hemmet (Home Journal; in 1886 replaced by Dagny) and Framåt (Forward; published in the years 1886-89). The background to this surge can be found in the increased interest in women’s issues in a broad sense. A very important impulse came from Fredrika Bremer’s novel of ideas, Hertha, eller en själs historia (1856; Eng. tr. Hertha). The book’s description of Hertha’s confined and stifling life conditions set off a debate that was afterwards not to be stopped and ultimately led to the 1858 passage in Sweden of the law that granted legal majority to unmarried women at the age of twenty-five.

With the 1869 translation into Swedish of John Stuart Mill’s On the Subjection of Women, the ground was laid for an improvement of women’s education and job opportunities. In 1874 the Swedish universities were opened up to women, who were now allowed to study all academic subjects except theology and advanced law. The historian Ellen Fries was one of those who availed herself of the new opportunity, and in 1883 she became the first woman to defend her doctoral dissertation in Sweden. Five years later, the medical student Karolina Widerström followed her example. Sonja Kovalevskij’s appointment in 1884 as Professor of Mathematics at Stockholms Högskola also signified an important break with tradition, as did Ellen Key’s lectures at the ‘Arbetareinstitutet’, the Workers’ Institute, in Stockholm.

The 1880s was a period of intensive creativity among female painters as well. Many of them got the chance to spread their wings thanks to their encounter with schools of art and artists’ collectives elsewhere in Europe, especially in France. Their portraits, and especially their self-portraits, indicate a new view of women and a new self-image.

The women who now gained for themselves a leading position as writers of fiction benefited from the direction that the public debate took during the 1870s and 1880s towards reform politics. Concurrently, a more theoretical discussion was conducted in newspapers and journals on the issues of marriage and morality, and on the nature of the woman and her ‘proper’ areas of activity, which were no longer considered obvious and innate. The passive, self-sacrificing, and asexual femininity was also being debated, and this stirred outrage in the more conservative circles. Not least a lecture by Knut Wicksell in Uppsala in 1880 drew both scandal and attention. Inspired by the English national economist Thomas Malthus and by George Drysdale, who maintained that sexuality was both female and male, he recommended contraceptives, not abstinence, as the only sensible solution to sexual frustration and unwanted pregnancies.

To Sophie Adlersparre, the leader of the established women’s movement, and to her sympathisers, such proposals were blasphemous and shocking, whereas the female authors – if they touched upon this sensitive issue at all – took up a more ambivalent attitude.

Stockholm

The female Modern Breakthrough had three centres in Sweden: Stockholm, Scania, and Gothenburg. In the capital, ‘Föreningen för gift qvinnas eganderätt’ (The Association for the Married Woman’s Right of Possession) had been formed by 1873 with its own series of publications, called Om den gifte qvinnans eganderätt (On the Married Woman’s Right of Possession). The work was successful in so far as, just the following year, a law was passed in Sweden that gave women the right to dispose of their own income. However, in most respects the man remained the legal representative of the woman, right up until 1921.

The period’s growing interest in the issue of morality was also provided with an organisational framework in Stockholm by the opening, in 1878, of a local chapter of the British, Continental and General Federation for the Abolition of Government Regulation of Prostitution (formed in 1875), which regarded state-regulated prostitution as deeply discriminatory against the women involved. The program of the federation was broadly in favour of emancipation but also had a somewhat rigid view of sexuality, both as regards marital and extra-marital relations.

In these circles, it was Sophie Adlersparre who set the tone, while the female authors took a more peripheral position. On the other hand, they often participated in the salon culture that still existed in Stockholm, where in particular the receptions of the professor couple Carl and Calla Curman were appreciated. In their home gathered the capital’s intellectual and artistic elite, among others Ellen Key, Alfhild Agrell, and Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler.

However, an even more important meeting-point for the radical circles in Stockholm was the so-called ‘Svältringen’ (The Circle of Starvation), established by Alfhild Agrell, Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler, Amanda Kerfstedt, and Ernst Lundqvist. They met in each other’s homes to hold readings, listen to music, and discuss new literature. Unanimous sources affirm that the gatherings were of great importance to the avant-garde of the 1880s, and in 1885 the Danish author Herman Bang reports to his friend and colleague Peter Nansen on a gathering of this kind in the home of Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler:

“The nicest people are the circle of Mrs Edgren. It is a slice of Europe in the midst of barbarism […]. All that is worth knowing in Stockholm turns up at Anne Charlotte’s, and she is an excellent hostess.”

‘Svältringen’ (The Circle of Starvation): the group of young avant-garde authors assumed this name to indicate that intellectual and artistic nourishment was all-important.

To the circle belonged such writers as the brothers Karl and Gösta af Geijerstam, Oscar Levertin, and Axel Lundegård. And among the women the most prominent, apart from Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler herself, were Ellen Key, Alfhild Agrell, and Sonja Kovalevskij, who also had ambitions to write fiction. But also for example the Finland-Swede Ina Lange was seen here, along with Mathilda Roos and Amanda Kerfstedt.

As early as in 1881, that is, three years before Björnson’s En Hanske (A Glove), Amanda Kerfstedt had demanded in her short story “Synd” (Sin) the same sexual abstinence before marriage from the man as from the woman.

The story was published in Finsk Tidskrift (The Finnish Journal), but its subject matter was considered so inflammatory that the editor, C. G. Estlander, felt called upon to intervene. In his introduction he distanced himself from the short story, since its “moral purpose was all too insistent” – to the men, one might add.

The women thus held a central position in the Stockholm camp of ‘radicals’, as also appears from the group’s plans, in 1883, of producing its own calendar. Nytänning (Reawakening) was to be the hopeful name of the publication. August Strindberg, who was one of those behind the initiative, had imagined that Mathilda Roos, Alfhild Agrell, and Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler, among others, would contribute. After just a few months, however, Strindberg’s enthusiasm had cooled, and the project came to nothing after he had rejected the contributions by both Agrell and Leffler. Gustaf af Geijerstam made a new attempt to gather ‘Det unga Sverige’ (Young Sweden) around another publication. Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler and Alfhild Agrell were involved in this endeavour as well. This time the project failed owing to the publisher’s hesitation with regard to the radical tone of the planned work.

With the publication of Strindberg’s Giftas I (1884; Eng. tr. Getting Married), in which his suspicious attitude to writing women is evident, the tentative understanding between him and the female authors was definitively over. Bernhard Meijer and others in the faction of the 1880s who did not want to be confused with Strindberg and his views now turned to Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler, “the most typical representative of ‘Young Sweden’”, as Meijer wrote, encouraging her to take the initiative to create a more “serious” association than ‘Svältringen’. Meijer also hopes for a journal and believes, as he writes in a letter of June 1885, “that fairly soon we will have a real party of the left in this country”. At the same time, he is careful to underline how important it is that Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler herself takes part in this. In January she had, however, already stressed her independence in a letter to Herman Bang. Under no circumstances did she want to be identified with “any party or be made to voice solidarity with anybody else; I want to go my own way, on my own”, she writes.

The same desire for integrity can be seen in Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler’s attitude towards the Fredrika Bremer Society. Just like Alfhild Agrell and Victoria Benedictsson, she never became a member. On the other hand, she is to be found, together with several other female authors from the 1880s, in a couple of other associations with specifically female overtones. One of these was Drägtreformföreningen (The Association for the Reformed Dress), and in 1885 at the Skansen in Stockholm, together with Sonja Kovalevskij and Alfhild Agrell, among others, she advertised the new and functional, so-called reformed dress for women. Leffler, Kovalevskij, and Agrell, along with Amanda Kerfstedt and Mathilda Roos, also turned up in ‘Nya Idun’ (New Idun), a women’s society of a more private character and a reply to the men’s club ‘Idun’, which had been established around 1860. Here, lectures were read and debates were held about contemporary women’s issues, and visiting female authors were also invited. One of these was Victoria Benedictsson, who lived in the province of Scania in southern Sweden and visited Stockholm in the winter of 1885, but who evidently felt a stranger in the literary milieu of the capital. In a letter to Amanda Kerfstedt’s son, the writer Hellen Lindgren, she exclaims:

“You are all from Stockholm, people of the world, bookworms, theorising philosophers. And I am not like the others: Mrs Edgren, Mrs Agrell, and Miss Roos. In comparison with them I am like a Christmas tree from Scania confronted with fine greenhouse plants. I cannot speak like them, cannot write like them, cannot think like them!”

Scania

In June 1886, a few young authors were gathered in Victoria Benedictsson’s home in Hörby. They discussed literature, talked about their writing plans and travels, and about Georg Brandes’s lectures in Copenhagen. It was Ola Hansson and Stella Kleve who had come to visit. The company felt their way forward, inquiring curiously.

Along with Axel Lundegård, who had also been invited to the meeting, Victoria Benedictsson and Stella Kleve had been reviewed together in an 1885 issue of the newspaper Sydsvenska Dagbladet Snällposten. Lundegård’s I gryningen (At the Break of Day) had been dismissed as “a rather ordinary debut novel”, whereas Benedictsson’s Pengar (Eng. tr. Money) had been warmly recommended by the reviewer – “the characters are lifelike and tangible” – and the reader had been guaranteed a pleasurable read. By contrast, Stella Kleve’s novella Berta Funcke (Berta Funcke), with its nervously jaded and indifferent characters, had made an “embarrassingly unpleasant impression” on the reviewer.

The authors’ impressions of their meeting were mixed. Victoria Benedictsson felt sceptical towards Stella Kleve’s “greenness”, which she perceived as superficiality: “The very keynotes of our characters are so different.” To Stella Kleve, on the other hand, the encounter with the older colleague was an experience: “There is something pure, almost abstractly intelligent about her whole person – she appears to be an incarnation of wisdom and clarity.”

“Stelle Kleve’s organism is not a healthy one. She has remarkably ugly teeth now, grey. They ought to be strong and white, for they are regular by nature. And her complexion is whitish grey. When she gets nervous, her hands become covered with small, round spots on a skin that is softer and redder than usual. The way she laces herself in! And then she has wrecked her digestion with sweets and her emotional life with books. A glorious product of too much culture. Does anyone believe that she would recover, if only she got married! Certainly not. Someone who is already so physically wrecked, and on top of this so utterly devoid of mental spontaneity, cannot be saved by a more natural sexual life. It is too late. And the life of her imagination has decayed.”

From Victoria Benedictsson, Stora boken 2 (The Big Book), 12 July 1886.

The meeting was already repeated in August in Stella Kleve’s home in Vetteryd, this time with Axel Lundegård and some Danish students as guests, and with the express purpose of creating the group ‘Det unga Skåne’ (Young Scania) as a south-Swedish counterpart to ‘Det unga Sverige’. They also wanted their own organ for presenting their views. The Gothenburg journal Framåt was considered to be too weak and the Danish newspaper Politiken to be an insufficient source of support. But the group’s agreement was illusory. The French-inspired, decadent literature that Ola Hansson and Stella Kleve wanted to introduce into Sweden was repugnant to Victoria Benedictsson. Despite her sympathy for Ola Hansson, she felt alienated from the ambitions of the younger authors. And when, in the autumn of 1886, Stella Kleve appeared in Framåt and poked fun at writing ladies and literature that echoed Henrik Ibsen, Victoria Benedictsson felt indignant on both her own and others’ behalf.

Ola Hansson and Victoria Benedictsson broke with one another upon the publication of the latter’s novel Fru Marianne in 1887. In Fru Marianne, the overly cultivated, decadent person – a recurring character in Hansson’s work – was dismissed as not being fit for life, and Ola Hansson also felt personally hurt by the novel’s portrait of Pål Sandell.

In a letter to Victoria Benedictsson, Ola Hansson airs his disappointment and bitterness over her novel Fru Marianne (1887; Mrs Marianne):

“The long and the short of it is this: the book does not satisfy my artist’s mind, and it has deeply distressed me as a contribution to what is the most heated dispute right now. The (quantitatively speaking) superior force of the opponent is already so overwhelming that a trump like the one the opponent has now been able to play in Fru Marianne can sting and make one bitter. That is more than enough already.”

The ambition of ‘Det unga Skåne’ to introduce late-Naturalistic poetry into Sweden was only partly fulfilled, for example in the articles that Ola Hansson published in Framåt. The critique was not merciful when it came to his collection of prose pieces, Sensitiva amorosa (1887; Eng. tr. Sensitiva amorosa), and Stella Kleve’s second novel, Alice Brandt (1888), was also shredded. Only Fru Marianne found favour with the conservative critics.

‘Det unga Skåne’ was an all too fragile construction. Ola Hansson left Sweden for Europe; Victoria Benedictsson moved to Copenhagen; and Stella Kleve licked her wounds in rural seclusion. The most lasting outcome of the endeavours of ‘Det unga Skåne’ was the work relationship between Victoria Benedictsson and Axel Lundegård.

Gothenburg

Greater similarities with the Stockholm milieu are found in the lively circle of young liberals in Gothenburg, who with the journal Framåt (Forward) succeeded in creating a forum for the debate of the 1880s. Here, then, was formed a third centre with a female profile in the Swedish Modern Breakthrough.

The journal Framåt, which was published in the years 1886-89, became the Swedish west coast’s reply to the journal Dagny, published by the Fredrika Bremer Society in Stockholm. The editor, Alma Åkermark, was, together with Mathilda Hedlund and Hilma Strandberg, the driving and active force behind the journal, with the ambition of making it a social and cultural forum that also reached out to the working class. Moreover, Alma Åkermark wanted to give the journal a distinctly Nordic stamp, for example by including Norwegian and Danish contributions in the original languages. Free debate was of capital importance.

“Do not judge anyone unheard. Free speech. Persuasion comes about through argument and counterargument.”

Vignette from the Gothenburg journal Framåt.

From the very beginning, Dagny and Framåt stood in opposition to each other. Headed by Sophie Adlersparre and the thirty-years-younger Alma Åkermark, respectively, the journals represented two generations of the Swedish women’s movement, who were fighting for women’s rights from different points of departure. In Framåt, all the women’s issues of the period were discussed, but Alma Åkermark warns against an exclusive focus on the women’s cause and stresses that the journal also wants to include men among its readers and contributors.

Framåt was to play an extremely important role in the literary and radical circles in Sweden, not least as a possibility for publication when other forums were closed. In the columns of the journal, a debate about contemporary women’s issues, which the editors wanted to put into a socio-political and economic perspective, was printed side by side with articles on aesthetic issues and literary contributions. During its short existence, Framåt was able to count among its collaborators all the Swedish authors of the 1880s, with the exception of Strindberg. Herman Bang and the brothers Georg and Edvard Brandes from Denmark as well as the Norwegians Jonas Lie and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson were also involved.

In connection with the ‘morality controversy’, Alma Åkermark did not shy away from publishing texts that were deemed provocative at the time, as for example Stella Kleve’s short story “Pyrrhussegrar” (Pyrrhic Victories); this led to an advertisement boycott of the journal. Towards the end of 1887, Alma Åkermark also published three witty and venomous articles by Georg Brandes, who wrote ironically about Elisabeth Grundtvig’s view of the female sex as angels devoid of sexual drive. This was too much for the Gothenburg readers, and a veritable boycott of the journal was launched.

“What I am asking is for the literati to step down a bit, to get together to give – not something to themselves for the pleasure of the moment – but to give something to the people as a whole, give little by little, and give in such a way that the general public can understand more, that it turns its taste away from the lighter, rather worthless magazine literature.”

Letter of 18 January 1889 from Alma Åkermark to Ellen Key.

However, the discussion of marriage continued in a series of articles by Urban von Feilitzen (under the signature of ‘Robinson’), who tried to mediate between the polarised views by pointing to the fact that both the advocates of free love and those who demanded that the men be pure regarded love as the necessary foundation for marriage.

Among the literary contributions it was not only Stella Kleve’s that caused offence. The sketch “Messling” (Measles) by Gerda von Mickwitz – about a women who is infected with syphilis by her husband – and Amalie Skram’s ghastly realistic serial novel “Et Ægteskab” (A Marriage) gave rise to heated discussion. A dispute also arose about the interpretation of Victoria Benedictsson’s Fru Marianne.

Despite the avant-garde’s appreciation, the opposition to the radical journal eventually grew so strong that Alma Åkermark and her husband, who were now the editors of Framåt and who had made great economic sacrifices to keep the journal above water, were forced to close it down. Alma Åkermark had even been dismissed from her position at the ‘Fruntimmersföreningens skola’ (The School of the Swedish Women’s Association). The couple took refuge in Finland; there, Alma Åkermark’s husband died of tuberculosis, whereupon she emigrated to the United States.

The Role of the Author

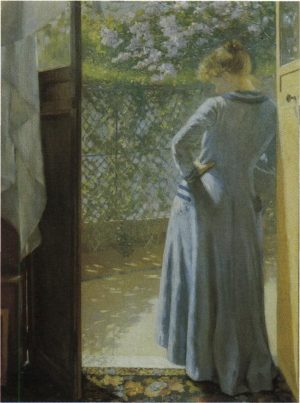

Eva Bonnier: At the Studio Door, 1885. Oil Painting. The Swedish State, Villa Bonnier

On the surface, the course of events in the early years of the 1880s pays testimony to female optimism, happiness, and confidence; women leave the confined space of the home behind them and go out into the world to find a place on the public scene. Now we also meet travelling female writers to a greater extent than before. They travel abroad to Denmark – to meet Georg Brandes –, to Norway, and to the continent, where Italy in particular is seen as both the promised and the controversial land. The most extensive formative journey was undertaken by Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler in the spring of 1884 in the company of the open-minded Julia Kjellberg, who some years later married the famous German Social Democrat Georg Vollmar. Their journey also included England, where especially the meetings in London with the Socialists August Bebel, Annie Besant, and Eleanor Marx made a great impression on Edgren Leffler.

“What I’ll miss the most when I leave London is Eleanor Marx. She is one of the four most interesting persons I have met, and I really like her as a friend […]. She is made of the same stuff as the martyrs and the heroines. She would be able to die for her cause […].”

Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler about the daughter of Karl Marx, in a letter of 26 May 1884 to her family.

In other respects as well, the authorial role that the female writers now took on had certain similarities to that of male writers. Unlike the authors of the previous generation with their wide-ranging novelistic art, the female authors of the 1880s prefer, as do their male colleagues, the travel sketch, the short story, stories about the lives of common people, the short novel, and not least the modern drama: the 1880s can boast of nearly as many female playwrights as all previous decades put together. Writing for the stage began to lose its threatening character, and there was a growing audience from the upper and middle classes who were keen on the new repertoire. Moreover, by analysing the position of women within and outside of marriage, the situation of the unmarried woman and the widow, as well as sexuality and the issue of morality, the women further develop the topics favoured by their male colleagues. Since these topics had now also appeared on the agenda of the male authors, they had become legitimate. For the female writer, however, they were more delicate to deal with. Nonetheless, she ventured to do just that.

“Earlier on, nay, just some ten years ago, a thinking woman would, on her visits to the theatre, every so often experience a feeling of emptiness. She had to wonder why the questions that often occupied her mind, why a woman of the kind of which she knew so many, never found their way to the stage […]. Now the state of things has changed. Moral issues of the most serious nature are being presented to the general theatre public.”

Tidskrift för hemmet (Home Journal), 1884.

Yet, below the surface one senses just how controversial the role of the female author still was. As a result of the nineteenth century’s generally insufficient girls’ education, there easily arose among the women feelings of intellectual inferiority or insecurity with respect to the university-educated men. Furthermore, the female writers were to be evaluated by a male-dominated body of critics who were influenced by gender prejudices. In addition, there were no female critics who supported them unreservedly. The judgements that were advanced, not only by the trend-setting critic Carl David af Wirsén but also in Tidskrift för hemmet and Dagny, were often based on morality. A text that dealt with eroticism, sexuality, or prostitution could be described as “repulsive”, “impure”, and “filthy”. Words of praise were, on the other hand, “masculine style”, “vigorous”, and “audacious”. In this light, the women’s use of pseudonyms becomes comprehensible, as do their, generally speaking, late debuts. The complexity of the writing situation was increased by the female author’s expectation that her endeavour would lead to economic independence, even if she were married. Like her male colleagues, she wanted to become a professional author who could make a living through her writing.

Carl David af Wirsén was Sweden’s leading conservative critic in the 1880s and 1890s, and, moreover, an influential Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy. The Swedish literary scholar Johan Svedjedal has pointed to Wirsén’s conservative view of women as a reason for the fact that, during this period, only four out of the sixty-nine authors who received the national grants awarded by the Swedish Academy since 1864 were women. The four were Mathilda Roos, Victoria Benedictsson, Selma Lagerlöf, and Josefina Wettergrund.

The Themes and Motifs of the 1880s

The problems associated with writing are reflected in the fiction as a dramatisation of the author’s role, sometimes in disguised form. The experience of being a female author, a subject acting and speaking on the public scene, is then described through a male character or through a fictive painter, musician, or actor. Something that the writing women also often return to is gender polarisation. Men and women appear to belong to different systems with widely differing values and norms. Although the woman sees the imperfections of the man, he nevertheless invades her thoughts and consciousness, in the same way as he dominated the actual private and public life of the late nineteenth century. Therefore, the focal point of several female texts becomes, after all, the depiction of a woman who, in her quest for the love of a man, ends up in a position of isolation that is not of her own active choosing. This love does not involve “partaking in the average happiness of life”, to quote the Swedish critic Oscar Levertin; it is the romantic dream of total and life-long mutual understanding. It is the realisation of this Ibsenesque utopia that is identical with “life”.

But naturalism à la Strindberg can also be found, for example in Anna Wahlenberg and Amalia Fahlstedt. In the context of the ‘morality controversy’, they adopted an independent point of view. In their texts, a wife may thus forgive her husband for having had both a sexual relation and a child before their marriage (Anna Wahlenberg), or a husband may forgive his wife’s infidelity during their marriage (Amalia Fahlstedt).

Another common motif is the dysfunctional mother-daughter relationship. While the relationship between mother and son is usually described as unproblematic, the mother or the older woman is seen as an obstacle to the development towards independence of the daughter or the younger woman. The use of metaphors that associate women’s existence with self-effacement, chaos, burden, and loss confirms the deeply pessimistic outlook of several of the texts. However, the pessimism is not unequivocal and consistent. The female authors of the Modern Breakthrough also offer positive pictures of women overcoming obstacles, increasing their understanding and strength, and being capable of adding new and greater substance to their lives.

“For a long while it was quiet.

– I think that my girl leaves me farther and farther behind, the feeble, trembling voice whispered.

Tensely, ardently, two arms were put around the mother’s neck, and in a low, wild, helpless voice she exclaimed:

– No – no, don’t say so; what does Mummy mean? Oh, I don’t know, what am I to do? When it is dark, as it is now, then I think about everything just as Mummy does, but during the day, then I think that everything is the way Daddy is. – Why is it so up and down – oh, can’t you help me, Mummy? – I’m so unhappy.”

Hilma Strandberg, “Från hennes barndom” (From her Childhood), in Framåt 1, 1886.

In other words, during this period the female fiction boasts a broad and nuanced spectrum that cannot be brought under one and the same formula. This diversity can also be detected in the descriptions of female sexuality. Stella Kleve’s outspoken texts provoked general dislike, whereas the same complex of problems was acceptable in a more conservative presentation. The recognition of sensual pleasure is decades away in this pre-Freudian period, in which the issue was that of finding the balance between ‘the angel of the house’, ‘the hysteric’, ‘the self-sacrificing mother’, and ‘the sexually loose woman’. It seems inevitable that the patriarchy’s images, which towards the end of the 1880s portray female sexuality to an ever-greater extent as threatening, stifling, and even deadly, also had an effect on women’s self-image. Salome, Medusa, the sphinx, vampires, and sirens become more or less bestial projections of the male fear of sexuality in the period’s decadent and avant-garde literature and art.

The Peak and the Backlash

The peak of the women’s surge was reached around 1886-87. At that time, Alfhild Agrell still enjoyed success, as did Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler, and the backlash had not yet reached Victoria Benedictsson. In 1885 Sofie Bertelson had her comedy about marriage, Efterspel (Epilogue), performed, and Lydia Kullgren’s Kärlek. Dramatisk techning ur hvardagslifvet (Love. A Dramatic Sketch of Everyday Life) was put up in Stockholm in the same year. As late as in 1886-87, collections of short stories or novels – for the most part, however, under the more unassuming designation of ‘long stories’ – were published by Elin Améen, Amalia Fahlstedt, Ina Lange, Anna Wahlenberg, and Mathilda Roos. In Gothenburg, the journal Framåt had just been launched, and Hilma Angered-Strandberg’s first novel appeared in 1887. But around the same time, a certain fatigue manifested itself in the literature that dealt with women’s issues. It is not without significance, either, that some years into the 1880s Georg Brandes, who had been the keenest advocate of a utilitarian view of literature, abandoned his ‘problem-debating’ programme. The French-inspired decadence set in, and the male colleagues who had earlier on shown their support of the women in appreciative terms became more and more defensive, or even openly negative.

Strindberg’s two collections of short stories, Giftas I and Giftas II (Eng. tr. Getting Married) set the tone, and whereas it was still humorous in Giftas I (1884), the introduction to Giftas II (1887) is decidedly aggressive and venomous against what he calls “the Nora woman” or “the cultured woman”. From some of the male critics, insinuations rained down about too friendly critique, lack of originality, and a court of chivalrous gentlemen serving as supporting troops. It was off-handedly asserted that the female writers’ ‘tendency novels’ made no difference whatsoever for the ongoing debate. The self-effacing and motherly woman was presented as a positive counter-image. The principle of the family was about to prevail.

“Because cowardly and lazy woman has driven man alone into war, the number of men has decreased. The male sex is also exhausted, because only man has worked to excess. Moreover, now that men are no longer inclined to allow themselves to be exploited by women in marriage, a large number of women are beginning to find themselves without husbands, that is without men to slave for them.

“Hence the enraged shouts of the female sex, which find expression in the so-called ‘Woman’s Movement’.”

From the Preface to Stindberg’s Giftas II (1887; Eng. tr. Getting Married).

Furthermore, in the autumn of 1886, Stella Kleve launched a frontal attack on Alfhild Agrell, Lydia Kullgren, and Sofie Bertelson in an article in Framåt called “Om efterklangs- och indignationslitteraturen i Sverige” (On the Swedish Literature of Imitation and Indignation). She wrote that, in theory, she agreed with the idea of equality between men and women, but that she preferred not to see it treated in the form of fiction; in this view she was supported by Ola Hansson. Alfhild Agrell replied to the charge, but apart from her, none of the other women came out in defence.

“To her, it is trite because two or three authors have happened to deal simultaneously with an aspect of it [i.e., the women’s cause]. To her, the struggle of one half of humanity to obtain equality and justice is already over, yes, even so much so that it can be dismissed with a laugh.”

From Agrell’s reply to Stella Kleve in Framåt, 1886.

That no expressions of sympathy were forthcoming from the female authors or Sophie Adlersparre can be seen as a symptom of an external crisis as well as a latent internal crisis among the women themselves. There was no united women’s front in the sense that in every respect the writing women made common cause with the organised women’s movement, or vice versa. What the female authors demanded was the liberation of the individual, not the ‘straitjacket of feminism’. Nor did they themselves constitute a homogeneous group that could unite around a common cause.

Also in a literal sense, the ranks were split. All the female authors who had ‘survived’ the 1880s continued to write, but as a consequence of the literary reorientation, these writers of ‘tendency novels’ experienced greater difficulty in asserting themselves. At the same time, the reforms towards a gender-equal society had come to a standstill. Compared to the 1860s and 1870s, when there had been eight legislative changes that benefited women, only one such change was passed in the period of the Modern Breakthrough, in 1884: an unmarried woman becomes legally of age when she is twenty-one. Eventually the increasingly influential Ellen Key recommended a new road for the woman, away from the focus of the early 1880s on the individual and away from that period’s emphasis on “the claim of the ideal”.

To several of the young women of the 1880s, who so hopefully streamed out through the open doors, the meeting with reality proved difficult. Some fell silent in disappointment and bitterness. And others invested their energy in education and teaching and in innovative writing for children. The Swedish children’s and young adults’ literature experienced its first golden age in the period 1890-1915. But many women defied the storm on the barricades and continued the campaign for emancipation that had been launched in the 1880s.

Translated by Pernille Harsting