In the 1970s, autobiographical stories written by women claimed centre stage on the literary scene. The autobiographical genres’ claim to truth became part and parcel of the feminist struggle and revitalised and popularised the genre of autobiographical fiction.

These were new stories offering new truths. And they soon became the subject of debate regarding both form and content. During the course of the 1980s, the publication of autobiographies by women plummeted before finally coming to an almost complete standstill. When interest in and publication of biographies gained strength by the end of the century and the early 2000s, the genre was no longer informed by feminism – though gender played a significant role and female writers constituted a pivotal driving force in the resurgence of the genre.

While biographic narratives had served as a means to claiming female subjecthood and establish new truths during the 1970s, by the 2000s biographical narratives had rather become an arena for various ways of challenging that very subjecthood and truth.

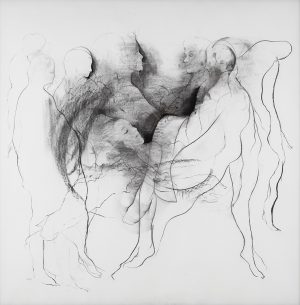

The complete and healing life stories sought after within traditional biographical fiction gave way to broken, fragmented accounts of enigmatic, multi-faceted, and intangible subjects. The very problem of narration often constituted a considerable aspect of the story. Above all, the boundary between fact and fiction, an important tenet of modern fiction, was dissolved. The purest form of autobiography and biography – like fiction in its purest form – had to give way to various crossover forms on the frontiers between fact-based biographies and fictional flights of fantasy.

As If It Were True: The Biographical Novel

Sigrid Combüchen set the course for the future trend with her novel, Byron: en roman (1988; Byron, 1991), a biographical novel about the frequently biographed Lord Byron, which demonstrated the impossible task of writing biographies while concurrently producing a new kind of novel, which borrows heavily from the biographical narrative form.

At the beginning of the novel, five admirers of Lord Byron attend the exhumation of the poet’s grave, something which actually occurred in 1938. They are searching for ‘the real thing ’ in order to understand their favourite poet better. Of course, they merely come across a pile of dusty remains bringing them closer to the truth of neither the poet nor his poetry. However, Combüchen allows each of the five characters to weave their own story around these bones. It is difficult to come by a more appropriate imagery depicting the handiwork of biography.

Not a single, unequivocal truth is generated here, but rather five independent, subjective, and mutually contradictive constructions. The sixth, conclusive story is constituted by the diary of John Hobhouse, written during the trip he made with Byron, which led to the poet’s death. While it appears to be a sober account relayed directly from the final months of Byron’s life, it is quite clearly a subjective story complete with wishful thinking and fantasy.

Even in the more traditional biographies published by Sigrid Combüchen during the 2000s, Livsklättraren: en bok om Knut Hamsun (2006; Life Climber: A Book on Knut Hamsun) and Den umbärliga (2014; The Dispensable), about Ida Bäckman, friend of the poet, Gustaf Fröding, and author Selma Lagerlöf, she juxtaposes multiple stories and shrouds the protagonists in mystery. She efficiently dismantles the traditional expectation of the genre, namely the existence of one truth only, by undermining any attempt at a conclusion and never summarising or stabilising the presentation of her subjects.

Several of the authors who, like Sigrid Combüchen, contributed to the biography boom at the turn of the millennium are included in Nordisk kvinnolitteraturhistoria, Volume IV (The History of Nordic Women’s Literature). Marie Helleberg, Helle Stangerup, Vibeke Olsson, Ragnhild Magerøy, and Sissel Lange-Nielsen have continued to write popular biographical novels about strong women throughout the history of Scandinavia and continental Europe. Anne Lise Marstrand-Jørgensen (b. 1971) is one of the foremost members of an emerging generation of female writers who are continuing and renewing this tradition.

Her breakthrough came with the two-volume biographical novel about the mediaeval mystic and abbess, St. Hildegard of Bingen. The first volume, Hildegard (2009), narrates her early years and monastic life up until the point, around the age of fifty, when the Pope recognises her visions as the work of God rather than the devil. In the second volume, Hildegard II (2010), she leaves the convent of Disibodenberg, where she has spent most of her life, in order to establish the new Rupertsberg convent.

Anne Lise Marstrand-Jørgensen’s Hildegard is a contradictory figure, she is extremely sensitive, almost fragile, and yet at the same time very forceful. She commands an extraordinary position during her time, but also pays a high price in terms of great suffering and severe solitude. The reader gains an insight into Hildegard’s innermost thoughts as well as her everyday life. The narrator, the biographer, is omniscient and there is no doubt that this is a work of fiction. However, by using the real names of historic people, places, and dates, and by describing events, which have previously been well-documented elsewhere, Marstrand-Jørgensen has created a text, which leaves the reader with the impression of engaging with a true, biographical narrative.

In her subsequent novels, Hvad man ikke ved (2014; What One Doesn’t Know) and Hvis sandheden skal frem (2014; Truth Be Told), Marstrand-Jørgensen ventures close to the genre of autobiography. The novels, set in the 1970s, caused quite a stir and were met with acclaim as well as pronounced resentment. The cover art places the novels in a not too distant and easily recognisable past. While it is a work of fiction, there is a considerable number of truth markers in the unfolding family saga.

Hvad man ikke ved begins in the eventful year of 1968. A man convinces his wife to join him in an open marriage of the new era. While he is enjoying himself, she loses her footing. She commits suicide before the end of the novel in 1974. The second volume, taking place between 1975 and 1992, focuses on her daughter Flora. During this period, the positive aspects of the women’s liberation movement flourish, as suggested by the protagonist’s name. Flora explores all of the new opportunities, which present themselves before she, “sated by the overabundance” and disillusioned, starts a family.

The novels describe an era of permissive social experimentation. In order to produce new ways of being and relating, no one is allowed to stake a claim on somebody else. Some people handle this new way of life better than others. In the first novel, women are particularly affected, in the sequel, the consequences experienced by men become more apparent. While many readers were outraged by Marstrand-Jørgensen’s perceived promotion of a 1970’s-style sexual liberation, others claimed that she had rather wanted to present a more complex account of the notorious decade.

True, Yet Not Quite True: Auto Fiction and Performance

The faith in the transformative powers of designation – so pronounced during the 1970s and which convinced female writers of the pivotal importance of narrating lived experiences – sprang from an imperturbable confidence in language and its ability to convey reality by way of a true account.

When stories narrating the female experience made a comeback at the end of the 20th and early 21st century, the idea that a true account of reality could be expressed through language had fundamentally changed. Now, language appeared as an obstacle rather than an asset in storytelling, and the boundary between fact and fiction was unclear. Autobiographies, diaries, and correspondence became integral to fictional accounts without the stories necessarily being authentic. Additionally, truth markers, including existing people’s real names, became part of primarily fictional accounts.

While the juxtaposition of fact and fiction had not been considered a problem in the field of biography, the new crossover genres, which came to be referred to as autofiction, were a source of confusion and dispute, particularly in the case of works written by women.

The publication of Carina Rydberg’s (b. 1962) Den högsta kasten (1997; The Supreme Caste) led to a formidable literary feud in the literary supplements of the leading Swedish newspapers. While the book was presented without a clear genre designation, the author had, during a string of interviews, characterised it as an autobiography, a true story, and underlined that this was indeed the entire point of the book. It is the story of her ambiguous experiences with love and men. Men, mentioned by name. At the centre of her disillusionment is the celebrity lawyer, Rolf. They move in the same fashionable social circles, dining in the same Stockholm restaurants, frequenting the same bars.

They begin to flirt and she invests herself emotionally only to find herself rejected and betrayed.

However, it was Carina Rydberg, rather than Rolf, who was exposed in the media. A heated dispute broke out, debating whether one ever has the right to portray somebody else in the way Rydberg had exposed Rolf by using his proper name. In a major article in the national newspaper, Dagens Nyheter, a prominent lawyer advised Rolf to take legal action against Rydberg. Several female critics came to Rydberg’s defence by pointing out that the book in question was a work of art in the form of eloquently written prose.

1997 may be considered the year of the turn from fiction to autobiography – or autofiction – in Nordic literature. This turn was by no means gender specific. The reception, however, was. The year Rydberg published Den högsta kasten was also the year Stieg Larsson published the autobiographical Natta de mina (1997; Good Night, My Loved Ones), a rhapsody of daily life composed of named celebrities, personal attacks, and bizarre sex. Rydberg and Larsson were both well-known, established writers, both books are primarily set in restaurants favoured by the literary set and both books were excellent sources of gossip. However, while Larsson’s numerous imprudent revelations and judgements regarding celebrities in Natta de mina went relatively unnoticed, Carina Rydberg’s account of the people, or rather the men, in her social circle became a cause for fierce debate.

When, three years later, Rydberg published the sequel, Djävulsformeln: roman (Devil’s Formula: A Novel), the critics had accepted the new development where books appearing as autobiography – and therefore apparently staking a claim to truth – should be read as fiction. Hence, Rydberg’s account of her failed sexual relationship with the notable artist, Ernst Billgren, caused hardly a stir. Ernst Billgren, however, took it upon himself to question the truthfulness of her account. He claimed that the story was simply a vengeful answer to his own fabrications in the autofictional account, Min kamp (1999; My Struggle), where he described Carina Rydberg as a lesbian.

However, this new reading of autobiography as a kind of fiction crashed with the publication of Maja Lundgren’s Myggor och tigrar (2007; Mosquitoes and Tigers), which sparked an even more virulent dispute in the culture sections of Swedish newspapers concerning women’s narration rights vis-à-vis actual, living men.

Maja Lundgren (b. 1965), was, like Carina Rydberg, an established author at the time of publication of her autobiographical novel. Her first novel, Sprickan i ögat (1993; The Crack in the Eye) was followed by the breakthrough, Pompeji: roman (2001; Pompeii: A Novel). Her account of everyday life in Pompeii a few days before the great eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, when time stood still, received well-nigh unanimous accolades from the critics. The novel was awarded the Svenska Dagbladet Literature Prize and shortlisted for the August Prize as well as two international prizes, the Italian Premio Bancarella and the French Prix Jean Monnet de Litérature Européenne.

Myggor och tigrar recounts Maja Lundgren’s life after the publication of Pompeji and her experiences of being excluded and overlooked despite her success. The novel portrays the overt and covert power structures of the cultural establishment and the particulars of the patriarchal hierarchy at the culture desk of the Swedish newspaper, Aftonbladet, where she occasionally works and at one point sleeps with the culture editor .

The book has no genre designation. The publishing house called it a novel, Maja Lundgren calls it a documentary autobiography. The narrative structure is cleverly thought out. It begins as something resembling a well-composed fictional short story before introducing various, more authentic modes of writing, such as e-mails and journal entries. This brings the writer consistently closer to the point, where the narrative appears to implode with life experiences in a crescendo, which finds her raped and subsequently met with disbelief when seeking help.

Maja Lundgren was as an individuel similarly met with disbelief. Upon publication of Myggor och tigrar, she was attacked, demeaned, and exposed as deranged in the press. The debate did not focus on the rape but on Lundgren’s portrayal of various male writers and critics, particularly staff from Aftonbladet’s culture desk where she used to work.

In Denmark, Christina Hesselholdt pioneered the literary trend of incorporating fiction into autobiography – or in her case, incorporating autobiography into fiction – in 1998. However, it occurred in a less spectacular manner than in Sweden.

Hesselholdt was already an established and renowned author when she published Hovedstolen (1998; The Principal), her first book which includes autobiographical material. She had carved out a strong position on the Danish literary scene with her trilogy about Marlon: Køkkenet, gravkammeret & landskabet (1991; The Kitchen, the Tomb, & the Landscape), Det skjulte (1993; The Hidden), and Udsigten (1995; The View). The trilogy is about a young man who is hurled into an identity crisis in the aftermath of his mother’s death and his father’s subsequent suicide. In these early works, Hesselholt had already developed the condensed narrative style, which has evolved consistently throughout her career. In Denmark, she has been the prime representative of the new form of short fiction and the introduction of the pointillist novel.

Hovedstolen, an autobiographical and brilliantly accomplished work, was her major breakthrough. According to the blurb on the back of the book, it consists of “fifty fictional accounts of a childhood”. However, it is essentially only the title of the novel, Hovedstolen – a retort to the announcement made by the Danish poet, Per Højholt, that writers ought to avoid the exploitation of their “biographical capital”, hovedstolen in Danish – which reveals that the stories are indeed autobiographical.

There are no names stated in the novel. The places are non-specific and the chronology fragmented. The text consists of individual, carefully crafted recollections characterised by loss, grief, and abandonment. Each recollection is a singular static entity. There is neither a chronology of events nor a plot. But at the heart of the story, one finds, like an open wound, a brief dialogue in which the protagonist’s father explains to her that he is about to leave her and her mother in order to live with another woman.

Fragmented identities and ossified, broken relationships are at the centre of Kraniekassen (2001, The Cranial Box), Du, mit du (2003; You, My You), and I familiens skød (2007, In the Bosom of the Family), the novels published by Hesselholdt before her return to autobiographical material. In Kraniekassen, Alice is in two minds about the five selves present inside her head. She is searching for a supreme ‘I’ but fearful of being merely a repository of various different, discordant selves, promising to haunt her until the end of time. Du, mit du depicts, in concise, almost melodramatic tableaus, a love affair where dying and killing are simply the flipside of the symbiosis of love. In I familiens skød, the author unfolds with sarcastic bravura the rigid pretense of social intercourse and people’s conceited attempts to reach out to each other.

The themes of Hesselholdt’s early works are not dissimilar to other contemporary works of prose. It is her concise and elaborate language, which makes her such a unique writer. The suite of novels, Camilla and the horse (2008; Camilla and the Horse), Camilla – og resten af selskabet: en fortællekreds (2010; Camilla – and the Rest of the Society: A Story-Telling Circle), Selskabet gør op (2012; The Circle Takes Stock), and Agterudsejlet (2014; Abandoned), adds new dramatic effects. However, the novels are, above all informed by a quirky sense of humour, which lifts the stories above and beyond themselves.

Hesselholdt creates a mutable narrative in the Camilla novels. Camilla and Charles, he is the ‘horse’, are the protagonists, but the vast number of characters in the suite is virtually impenetrable and the point-of-view is constantly shifting. The protagonist of one story may very well appear as a minor character or a triviality in other stories. The numerous narratives interweave in a captivating manner, adding up to a bigger picture in which the particulars are concomitantly finite and constituent parts of a bigger whole.

In interviews, Christina Hesselholdt has underscored the autobiographical nature of the books. With reference to the concluding novel of the suite, Agterudsejlet, which consists of fourteen monologues about the death of a mother, divorce, attempted murder, and depression, she has described in great detail the burden of writing through ‘ family matters’. However, she has vehemently dismissed biographical readings and various critics’ attempts to disclose the names of the characters. To Hesselholdt, literary fiction remains separate from real life. To her, autofiction is a method to create distance rather than a search for truths about real life. It is not the case of true life but of true fiction.

True + Not True + Not Not True = New Truths

The new literary hybrids, where biographical modes of expression are integrated into the novel and fiction has been included in biography, were read by many as true stories while others, particularly professional readers, chose to understand everything as fiction. In Sweden, one work of autofiction kicked off a new and intense feminist debate about the true state of affairs between the sexes in the noughties. Maria Sveland (b. 1974) elicited a new debate on the question of equality between the sexes with Bitterfittan (2007; The Bitter Cunt). It is, like Hesselholdt’s books, a work of fiction, but was nevertheless read as a true account of life.

At the start of the book, Sara is on a flight to Tenerife. She has left her husband and children behind for a week’s ‘time-out’ in order to gather her thoughts. Though she is merely thirty years old, she feels exhausted and embittered, and cannot help thinking about all the worn-out women giving their all to their families. She has brought Erica Jong’s feminist ‘70s classic, Fear of Flying (1973), along on the flight and cannot help wishing it was 1975 rather than 2005. Back then, everything appeared to be possible, fun, and liberated. While Sara finds many similarities between herself and Jong’s Isadora, she does not personally long for a “zipless fuck”. Contrary to Isadora, she is a mother and she longs for peace and quiet and spending some time on her own.

Bitterfittan is a furious confrontation with pervasive notions of love and motherhood. The book had a massive media impact and became a cult object for the younger generation of feminists of both sexes. It did, however also annoy some older feminists who considered the young ones to be ungrateful moaners.

The Danish writer, Suzanne Brøgger, is one of the authors referenced by Sara in Maria Sveland’s Bitterfittan. One may argue that Bitterfittan completes and develops further the genre, which Brøgger claimed for herself in the 1970s, namely the literature of experience. While Brøgger put authenticity before fiction in the 1970s, Sveland puts fiction first.

Suzanne Brøgger did the same at the end of the 1990s when she completed the great family saga about the Danish-Jewish Løvin family. Jadekatten: en slægtssaga (1997; The Jade Cat, 2004) was a novel with easily recognisable autobiographical elements. As was Til T: roman (2013; For T: A Novel), which Brøgger calls her first novel. “My earlier books have primarily been ‘I-books’, or autofiction/essays,” she said upon the publication of Til T.

In the novel, which is set during a few days of summer in Denmark in 1958, Suzanne Brøgger dissects the life of a family sharing obvious similarities with the family she has portrayed in her previous books. It is a family drama, written with a tremendous sense of humour and subtlety, and deeply tragic.

The mentally unstable mother is addicted to prescription medicines, she is charming but distant, egocentric, and overbearing. The father dreams of leaving, while the two sisters anxiously attempt to navigate between the emotional states of their parents. Family life is like a role play, where the parts are continuously rewritten. One may describe it as a nightmare, however Suzanne Brøgger imbues her story with a lightly comic and surrealistic touch. After only a few pages of the book, the mother renames all the family members after the animal characters in Milne’s Winnie the Pooh. Til T is a dark fairy tale, weaving fact and fiction together in not entirely transparent ways.

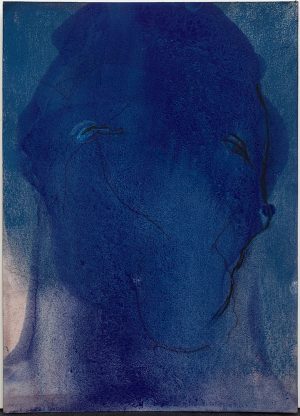

On the occasion of her seventieth birthday, Brøgger published a more traditional autobiography entitled SZ – et livs billeder 1944-2014 (2014; SZ – Images of a Life 1944-2014). The book is a collage of her life and oeuvre. And it becomes patently clear that she is an integral part of her work beyond the narrow confines of biography. She, her face, and her body are all parts of the self-staging, which includes her literary output. The title of the book refers to her initials as a married woman, Suzanne Zeruneith, and the book covers the whole spectrum from private snapshots to her most spectacular performances. Today, Suzanne Preis Brøgger Zeruneith is considered one of the foremost writers of autofiction and performance literature.

Issues pertaining to the questioning of the authentic and the possibility of rendering descriptions of the authentic also came to the fore in Agneta Klingspor’s (b. 1946) Nyckelroman 1977-1992 (1994; Roman À Clef 1977-1992). The book is the sequel to her widely publicised journals published in 1977, Inte skära, bara rispa: kvinnodagbok 1962-1976 (Do Not Cut, Scratch Only: Woman’s Journal 1962-1976), and analysed in an article, ‘To Write Oneself Free’, in volume IV of Nordisk kvinnolitteraturhistoria.

While, in the 1970’s, the controversial journals were launched as an uncensored, frank report from her personal life, the journal notes from 1977-1992 are marketed as a novel. While Klingspor’s face appears on the cover of the first book, on the cover of the second book, her face is covered by a mask. Several critics chose to read Nyckelroman as a work of fiction, despite the fact that it is quite obviously a sequel to the previous tome in terms of form, content, and uncompromising attitude towards the subject matter.

When Klingspor published the complete diaries in a single six hundred-page volume paperback edition with the brief title Dagböckerna 1962-1992 (2013; The Journals 1962-1992), the cover boasted the face of an unmasked woman. The critics were once more ready for a biographical reading, however, unlike their 1970’s counterparts, they were no longer appalled – rather, they considered the journals a grand document of time, chronicling a woman’s life during the final part of the 20th century.

A Measure of Truth

After the first decade of the millennium, Herbjørg Wassmo (b. 1942) and Kerstin Ekman (b. 1933), two well-established and much-loved writers, challenged the book market’s penchant for biographical fiction on one hand and the general rejection of the possibility of anyone actually narrating the truth on the other hand. Each of them reject contemporary expectations of autofiction from their own standpoints while they, at the same time, both use autofiction as a device in their novels, Hundre år (2009; Hundred Years) and Grand final i skojarbranschen (2011; The Grand Finale of the Dodgers’ Business)

In Hundre år, Herbjørg Wassmo approaches the emotional capital, or in the words of Højholt and Hesselholdt, the principal, of her oeuvre. In her breakthrough trilogy of the 1980s, Huset med den blinde glassveranda (1981; The House with the Blind Glass Windows, 1994), Det stumme rommet (1983; The Silent Room), and Hudløs himmel (1986; Sore Sky), the main protagonist is a girl named Tora, who was raped. A child of a Norwegian mother and German soldier from the occupation forces during World War II, Tora’s molester was her foster father. In Hundre år, the girl is named Herbjørg, and her molester is her own father. However, this does not entail that Hundre år is either autobiography or autofiction. While Herbjørg Wassmo demonstrates that there was indeed a girl named Herbjørg – who shared the same experiences as Tora and Herbjørg Wassmo, the author – and she spoke to the media about the difficulties of writing about one’s own experiences, Hundre år is nevertheless a novel, which appends the story of Herbjørg to the account of a century-long women’s family saga. With their suffering, Tora and Herbjørg become yet another couple of slight characters among the multitudes of suffering women in history.

Kersting Ekman divides the protagonist in Grand final i skojarbranschen in two. The beautiful Lillemor shares many similarities with the author. She starts out as a crime novelist before writing critically acclaimed novels, becoming elected to the Swedish Academy, and so on and so forth. Lillemor looks like Kerstin Ekman, she does up her hair like Kerstin Ekman, and wears the same clothes as Kerstin Ekman has been photographed wearing. And then there is the ugly, coarse, uncouth, and revolting Babba. The problem is that the pretty and lovable Lillemor cannot write. Babba is the author of the novels attributed to Lillemor, novels, which have made her a firm star in the literary market. When Lillemor wants to call off their collaboration, Babba hands in a manuscript to another publishing house where she tells the true story behind the work. Scandal beckons, but Lillemor saves herself by branding the text as autofiction. Thus, their collaboration may continue.

Grand final i skojarbranschen includes numerous direct references to a discernible reality, but the facts are continuously founded in uncertain terms. It is as if Ekman wants to say that truth and the act of writing about truth is concomitantly difficult to access and imbued with ambiguity. Literature is not created in the eye of the public but within the darkness of secrets. The one who writes remains invisible and when you write, you become what you, as a woman, cannot be in society.

Fiction

- Ernst Billgren: Min kamp. Bokförlag DN, 1999

- Suzanne Brøgger: Jadekatten: en slægtssaga. Gyldendal, 1997. The Jade Cat, Harvill Press, 2004

- Suzanne Brøgger: Til T. Gyldendal, 2013

- Suzanne Brøgger: SZ – Et livs billeder 1944-2014. Gyldendal, 2014

- Sigrid Combüchen: Byron. En roman. Norstedt, 1988. Byron, Trafalgar Square Publishing, 1991

- Sigrid Combüchen: Livsklättraren: En bok om Knut Hamsun. Albert Bonniers Forlag, 2006

- Sigrid Combüchen: Den umbärliga. Norstedt, 2014

- Kerstin Ekman: Grand final i skojarbranschen. Albert Bonniers Forlag, 2011.

- Christina Hesselholdt: Køkkenet, gravkammeret & landskabet. Rosinante, 1991

- Christina Hesselholdt: Det skjulte. Rosinante, 1993

- Christina Hesselholdt: Udsigten. Rosinante, 1995

- Christina Hesselholdt: Hovedstolen. Rosinante, 1998

- Christina Hesselholdt: Kraniekassen. Rosinante, 2001

- Christina Hesselholdt: Du, mit du. Rosinante, 2003

- Christina Hesselholdt: I familiens skød. Rosinante, 2007

- Christina Hesselholdt: Camilla and the horse. Rosinante, 2008

- Christina Hesselholdt: Camilla – og resten af selskabet: en fortællekreds. Rosinante, 2010

- Christina Hesselholdt: Selskabet gør op. Rosinante, 2012

- Christina Hesselholdt: Agterudsejlet. Rosinante, 2014

- Agneta Klingspor: Inte skära, bara rispa: kvinnodagbok 1962-76. Prisma, 1977

- Agneta Klingspor: Nyckelroman 1977-1992. Norstedt, 1994

- Agneta Klingspor: Dagböckerna 1962-92. Atlas, 2013

- Stieg Larsson: Natta de mina. Bonniers Forlag, 1997.

- Maja Lundgren: Sprickan i ögat. Norstedt, 1993

- Maja Lundgren: Pompeji. Albert Bonniers Forlag, 2001.

- Maja Lundgren: Myggor och tigrar. Albert Bonniers Forlag, 2007

- Anne Lise Marstrand-Jørgensen: Hildegard. Gyldendal, 2009

- Anne Lise Marstrand-Jørgensen: Hildegard II. Gyldendal, 2010

- Anne Lise Marstrand-Jørgensen: Hvad man ikke ved. Gyldendal, 2012

- Anne Lise Marstrand-Jørgensen: Hvis sandheden skal frem. Gyldendal, 2013

- Carina Rydberg: Den högsta kasten. Albert Bonniers Forlag, 1997.

- Carina Rydberg: Djävulsformeln. Albert Bonniers Forlag, 2000

- Maria Sveland: Bitterfittan. Norstedt, 2007.

- Herbjørg Wassmo: Huset med den blinde glassveranda. Gyldendal, 1981. The House with Blind Glass Windows, Seal Press, 1994

- Herbjørg Wassmo: Det stumme rommet. Gyldendal, 1983.

- Herbjørg Wassmo: Hudløs himmel. Norstedt, 1986.

- Herbjørg Wassmo: Hundre år. Gyldendal, 2009.

- Eric Almquist: ”Sanning & konsekvens”. Filter, 2010

- Carsten Andersen: ”Jeg kan ikke holde på hemmeligheder”. Politiken, 30.08.2008

- Linda R. Anderson: Autobiography. Routledge, 2001

- Jon Helt Haarder: Performativ biografisme. Gyldendal, 2014

- Paal-Helge Haugen: ”Christina Hesselholdt”. Danske digtere i det 20.århundrede III. Fra Kirsten Thorup til Christina Hesselholdt, A.M. Mai (red.). Gad, 2000

- Karen Hedeman: ”Min version af Hildegaard”. Litteratursiden.dk, 02.02.2011

- Mette Østgaard Henriksen: ”Selvbiografi og selvperformance går hånd i hånd i Lone Hørslevs digtsamling ’Jeg ved ikke om den slags tanker er normale’”. Litteratursiden.dk, 23.11.2012

- Elisabeth Møller Jensen (red.): Nordisk kvindelitteraturhistorie IV. Rosinante, 1997

- Lisbeth Larsson: Sanning og konsekvens. Marika Stiernstedt, Ludvig Nordström och de biografiska berättelserna. Norstedt, 2001

- Lisbeth Larsson: ”Suzanne Brøgger”. Danske digtere i det 20.århundrede III. Fra Kirsten Thorup til Christina Hesselholdt, A.M. Mai (red.). Gad, 2000

- Lisbeth Larsson: ”Självbiografi, autofiktion, testimony, lifewriting”. Tidskrift för Genusvetenskap 4, 2010

- Christian Lenemark: Sanna lögner, Carina Rydberg, Stig Larsson och författarens medialisering. Gidlunds Forlag, 2009

- Lena Malmberg: ”At skrive sig fri”. Nordisk kvindelitteraturhistorie IV. Rosinante, 1997

- Annemarte Moland: ”’Han var en trussel mot min kropp og sjel’”- Norsk rikskringkasting, 19.09.2009: http://www.nrk.no/kultur/wassmo-forteller-om-overgrepene-1.6783103

- Anna Remmets: ”Återupptäck Agneta Klingspor”. Fria tidningar, 15.03.2013: http://www.fria.nu/artikel/96934

- Cristine Sarrimo: Jagets scen: självframställning i olika medier. Makadam Forlag, 2012

- Max Saunders: Self Impressions: Life-Writing, Autobiografiction, and the Forms of Modern Literature. OUP Oxford, 2010

- Dorte Hygum Sørensen: ”Jeg har brug for at gøre noget, jeg ikke er sikker på”. Politiken, 12.02.2013

- Karen Syberg: ”’Jeg har intet ønske om att travle igennem livet alene’”. Information 09.05.2015

- Sidonie Smith og Julia Watson: Reading Autobiography: a guide for interpreting life narratives. University of Minnesota Press, 2001

- Louise Zeuthen: De virkelige halvfjerdsere. Krop, køn og performativitet hos Suzanne Brøgger og Kirsten Thorup. Ph.d.-afhandling. Københavns Universitet, 2000

- Louise Zeuthen: Krukke: En biografi om Suzanne Brøgger. Gyldendal, 2014