There has been talk of a turning point in the literary climate of Sweden around 1975. The crisis in the publishing industry that had seriously inhibited the publication of unprofitable literature, in particular, is over, and new poets make their debut in part thanks to state publishing subsidies. Space is found for a more nuanced and changing prismatic view of what poetry is and can be. Inner reality begins to be accorded its full significance, as do specifically female experiences.

Modernism’s full, rich arsenal of expressions – rooted in symbolism and Romanticism – is available to those women poets making their debuts in the second half of the 1970s who will become the foremost of their generation: Marie Louise Ramnefalk, Eva Runefelt, and Elisabeth Rynell in 1975, Eva Ström and Bodil Malmsten in 1977. They are contemporary with the new women’s movement, and they depict sensuality, eroticism, the dark language of gender, and the peculiar spiritual and bodily landscape of motherhood in very different ways.

Siv Arb – A Builder of Bridges

Siv Arb (born 1931) has described herself as one of literature’s assisting crones; she has worked as an editor, a literary critic, and a translator. She expressed a feminist consciousness early on, and she has been a sisterly model and conversational partner in each meeting, both giving and taking, as Eva Runefelt, among others, has testified. Runefelt speaks about her relationship with Arb in a conversation with Sonja Åkesson in Bengt Martin’s 1984 biography Sonja Åkesson.

Siv Arb made her debut at the Metamorfos publishing house in 1959 with a typed booklet, Växt mot vinden (1959; Growth Against the Wind), and already in her debut work, she underlines the reader’s capabilities for understanding and co-creation, something that links her to the poets of the New Simplicity school, appearing in the early 1960s. The desire to give her poetry a clear structure can, in the work of Siv Arb, give the poems an almost ascetic and occasionally abstract appearance. Many of her poems have an urging tone – directed towards the reader, but as much towards the inner self. Siv Arb does not seek to convey the kitchen sink realism of everyday life, but rather a ‘perceptive’ sensibility in the face of each moment’s subtle sensations.

While her debut collection contained quite a bit of melodious poetry of 1950s extraction, Kollisioner (1967; Collisions) intended, as the title indicates, to wage significantly tougher battles with reality: a self that seeks a precarious balance between silence and break-up, between sterile isolation and the world’s too pushy characters, between a need for integrity and a longing for fellowship. With her socialist conviction, Siv Arb was committed to the Vietnamese people. Environmental questions have affected her deeply, and one of her poems was printed on a poster during the anti-nuclear power debate before the referendum in 1980.

The feelings of alienation and disconnectedness cannot just be reduced to a reaction to late capitalist society; Siv Arb’s personal childhood trauma (being raised without a father, early separation from the mother, foster-care), which she has spoken about in plain terms in later interviews, plays an important part. In the collections of poems from the 1970s, Burspråk, (1971; Oriel), Dikter i mörker och ljus, (1975; Poems in Darkness and Light), and Under bara himlen, (1978; Under the Naked Sky), her experiences are worked over in something that resembles a psychoanalytic downward and upward journey through the paralysis of loss, anxiety, and depression, in which she also takes on the role of interpreter for the many who have been silenced.

In 1990 a beautiful volume of poetry illustrated with autobiographical collage was published: Siv Arb’s Ingens början (1990; Nobody’s Beginning). The collection contains a solid selection from previous works, eighteen newly written poems, and a preface by Eva Runefelt. Siv Arb’s significance in introducing and inspiring other poets is confirmed in this clear-sighted insider portrait by a friend. Eva Runefelt met the older poet in connection with the first large poetry reading in Gamla Riksdagshuset (the old parliament building) in Stockholm in May 1973, an event organised by Siv Arb.

To her, language is not a cage but a position that lends perspective and the possibility of depicting original loss: through rendering it visible, reconciliation becomes possible.

The poems do not convey facile didactic wisdoms; the pain remains intact. But Siv Arb’s later poetry collections, Livs levande (1984; Living Alive); the great summation of her work in Ingens början (1990; Nobody’s Beginning), which also includes freshly written material; and Nattens sömmerskor (1994; Summer Shoes of Night), express a sort of non-denominational pious outlook on life.

Have you ever felt

how the chair you’re sitting on

is more

real than you are?

Have you ever felt

how an object kidnaps you,

and then refuses

to show you where you are?

How long might it take

to find yourself;

turn and twist the doodahs,

use the thing instead of

the other way around!

Siv Arb: “Tingen kidnappar dig” (Objects Kidnap You), Burspråk (1971; Oriel)

Language Work

Eva Runefelt (born 1953) has made frequent mention of modernism’s extraordinary claims to language as a tool that allows the creation – not depiction – of its own reality. But the sphere of art is never quite autonomous; the poet takes surrounding reality as her point of departure, just as the poem takes its beginning in an actual space-time. In her first books, the will to communicate is a powerful motivator.

Eva Runefelt’s first attempt to write was under the auspices of the socialist cultural magazine Konflikt (Conflict 1973-1975), and she participated in the poetry reading at Gamla Riksdagshuset in 1973, when Konflikt published “Första 70-talsantologin” (The First Anthology of the 1970s).

But Eva Runefelt’s poetry has also been called impenetrable because of its dense language, which wants to remain true to sensory impressions, and creates a suggestive world of its own from these. Physicality takes precedence over words: she has called the opposite attitude utter ‘madness’. Sight – an uncommon sensitivity to light – taste and touch exist first, and may then be united in words, sounds, and alliterations; the order of words is often decided by the rhythmic tonality. In the collection Augusti (1981; August), Runefelt’s poetic technique appears even more polished: she prunes the sensory impressions, and works actively with the rhythmic possibilities of the verse. The modernist utopian striving to ‘save’ reality and the dream are possible only in the text, where resurrection has already taken place, as here in “Polderland”:

Like hovering reflections

short horses graze

the green waters of light polders

The animals disappear

and are resurrected

in the angled light; brain light

Weightless

It is after the resurrection, April

The repose of big fields

for years

which gives root to a new growth

Grass-birds, avenues of wind-roses

and the carmine lights of the nights

not yet full-blown

Augusti (1981; August) takes a love story for its theme, and has a sensing self at its core. Eva Runefelt’s latest collection of poems at the time of writing, with the characteristic title Längs ett oavslutat ögonblick (1986; Along an Unfinished Moment), is even more clearly rooted in her biography. The collection is based on her travels in Canada, Denmark, and the south of France. Formally, Runefelt is taking fastidiousness and winnowing to another level, a tendency also seen in the poem that, along with Stina Strandberg’s pencil sketches, makes up the little booklet Ur mörkret (1983; Out of the Darkness).

Runefelt still operates with the mystery of a line of words forming a personal code system, the keys to which she does not lend out. Thus, the sensual imagery can appear paradoxically ‘chaste’, and the poetic speaker can appear to be de-personified: a registering and structuring function that builds its own world of strange beauty.

Following the publication of Längs ett oavslutat ögonblick (1986; Along an Unfinished Moment), it took eight years before Eva Runefelt again trod the literary boards. In the intervening period, she gives birth to a daughter and moves for a few years to Värmland with her family. The child grows, and sketches are collected in folders. When the short story collection Hejdad tid (1994; Stopped Time) is published in January of 1994, it is a huge success with the critics. Here, the reader encounters a form-conscious lyrical prose that is at once strongly sensual and goes beyond normal limits. Eva Runefelt is back.

With Irony for a Weapon

From the very beginning, the critic and literary historian Marie Louise Ramnefalk (born 1941) emerges as a full-blooded ironist with a kinship to Karl Vennberg and T. S. Eliot, but with a temper unquestionably her own. Her poems reflect a woman’s vulnerability, grief, longing, and anger. Here, the gender problems are clearly spelled out. The harsh criticism of a society that targets career mentality, opportunism, therapy jargon, ideological purity, fanaticism, and other versions of modern, secular ways of life, is juxtaposed with an existential-religious theme that increases in importance in her later writings.

Enskilt liv pågår (1975; Private Life in Progress) should, according to the author, be seen as a report on middle class soul-seeking: dramatic monologues of a sort, or suites of solo songs. In the following collection, Verkligheten gör dig den äran (1978; Reality Would Like the Honour), she addresses herself to her daughter in the manner of a latter-day Mrs Lenngren

Saga, myth and dream are also important components in Elisabeth Rynell’s novel En berättelse om Loka (1990; A Tale of Loka), in which two narrations are woven together: one about Loka on a walk in the forest in an, as it appears, distant past, and the other a first person narrative set in the present – which actually is not any less absurd. The exactitude of the increasingly nightmarish reality and the summarised dream are almost reminiscent of Franz Kafka. “Sometimes I think that I live several lives simultaneously and that the different lives send weak signals to each other.” Is Loka the first person narrator’s dream? Do any of them ‘exist’ at all? The ‘tale’ of Loka is, just like the modern nightmare, highly suggestive; Elisabeth Rynell leaves it to the reader to interpret and connect them.

:

Provided with glasses, dental correction

and enrolled in a training program to improve motor function

in short, with multiple defects

she awkwardly hops her way to school age.

Dear god, little child, I love you

twisted and warped, latently cross-eyed, near-sighted, overhauled

harelipped, with overbite and a protruding jaw and badly con-

founded fingers

a sense of balance that hardly satisfies Child

Welfare Services

as the miracle that you are, uncorrected.

The three collections that Marie Louise Ramnefalk published during the first half of the 1980s confirm the impression of an unerring satirist who lampoons the modern society of committees and bureaucracy with its professionally smooth moral arrivistes and therapy careerists. Ramnefalk directs well-aimed verbal kicks at male, sensitive shins, but she is also capable of being cruel and joyfully nasty towards her fellow sisters.

Impure Aesthetics

The title of Elisabeth Rynell’s (born 1954) debut, Lyrsvit m.m. gnöl (1975; Lyre Suite etc. moaning), reflects two sides of her poetic temper: the lure of the highflown and ecstatic, and an ‘impure’ aesthetics that does not shy away from what is ugly or low:

Beautiful songs are not born from the bawl of abortion

do not seethe in a cooking salt solution

nor in bloodied phlegm

on the morgue birthing sheet

No, not here

not in nights without eyes or song

Not here

where everyone is alike unto irrecognisability

painted whores

sold for a crummy fuck

The collection was written as a crisis reaction after a trip to India, and Lyrsvit m. m. gnöl offers – in spite of the abortion screams and women giving birth astride a grave – testimony of a more common world conscience, while the broken lyre rather stands for a Baudelairian, demolished yet invoked, Orphic ideal where the poet at once lays claim to and denies her exalted position. The novel Veta hut (1979; Knowing Impudence) seeks to adapt to the political debate novel by having two male antagonists, the reformist and the extra-parliamentarian, for main characters. The book prompted heated debate, and Elisabeth Rynell was accused of sympathising with terrorists and Fascism – a factor in her decision to leave Stockholm and settle in Norrland with husband and child. In Onda dikter (1980; Evil Poems), the pathos is still hammered out in capital letters and civilisation-critical exclamation points. The city’s cold half-life, its repulsive fascination, is still an important motif. But there is simultaneously an ongoing spiritual search, taking place in pain and in darkness: the prophecy of doom is countered by a playful, still ecstatic sensuality that in later collections is more solidly grounded in, and even merges with, the natural beauty of Norrland.

Sjuk fågel (1988; Sick Bird), created in part under the influence of the Chernobyl disaster, takes for its theme the overwhelming threat against civilisation: the vomiting bird fills the sky with all sorts of repugnance: “copper suns, children, and woodchips”, and the self is threatened by loss of identity and language, when “the great faceless” erases all. But counter-forces are invoked; there is a strong and good wind blowing in the mountains, which will make everything right: “I believe. I believe in a life after this one.”

The tone is different in Nattliga samtal (1990; Nightly Conversations), an elegy for her husband, who unexpectedly forsook her in an abandoned, scoured world of sharp outlines. With a naked candour and, at times, an almost bitter terseness, she seeks to rein in the pain. The poetry resembles old Icelandic songs of lament. Simply, and with clarity, these poems touch and name the most immediate correlations of loss: skin caressed by his hands, boots standing empty, the children and animals of the farm … There is no easy reconcilitation with life; the poetry is utterly inconsolable: “And it is a silencing / and it is a quiet / and it is life”. Life goes on in Öckenvandrare (1993; Desert Wanderer). The address is conscious and authoritative in these new poems: “Words move / animal-like in the mouth I / know them / Bite down”. A strong and dangerous, dark sensuality speaks that may remind the reader of Eva Ström’s poetry: a multitude of insect lives, the odours of the body, a vibrant growth bordering on decomposition. The counterpoint to this sensuality is the poem, words as a dream of order, and beyond that is a “joy without signs”, Existence itself.

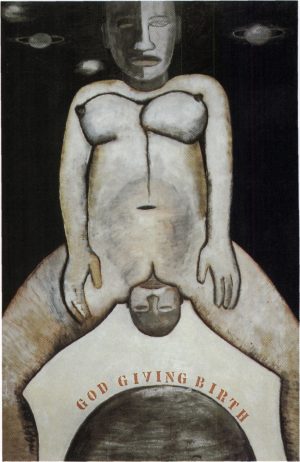

Eva Ström’s Det mörka alfabetet (1982; The Dark Alphabet) is an experimental novel with strong lyrical traits. Its motto is a poem from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Das Stunden-Buch (Eng. tr. The Book of Hours) that among other things asks the troubling question: What are you going to do, God, when I die? Without a human consciousness to dwell within, God loses meaning. Is God made in the image of mankind and not the other way around? Is he, like the human being, simply a consequence of the genetic code that carries creation’s dark alphabet in its messenger RNA? How is a human being’s consciousness and outlook on reality shaped by linguistic structures? That is the basic theme and perspective on life that Eva Ström dramatises in a hospital environment.

Linguistic Grief Work

One of the most unique and strongest voices among writers making their debuts in the 1970s was that of a physician and mother of small children living in Kristianstad – Eva Ström (born 1947). In her collection Den brinnande zeppelinaren (1977; The Burning Zeppelin), a strange ability to generate imagery is revealed in a language that draws its rich metaphors from collected sensory experiences of the world. Not least the hospital environment, and the imagery this generates, plays an important part in a language that breaks against the romantic and the brightly coloured props and rhetorical tropes of symbolism. Eva Ström herself speaks of a ‘poetry of inhalation’ that is still gasping for breath in the face of sensory experience. She erects a world of dream logic: an irrational yet still curiously obvious poetic universe, where polarities are described in terms of soft and hard, dissolution and petrifaction, emotion and reason, biology and technology: women’s experiences of sexuality and giving birth, the gender’s distinctive language versus male rationality.

The real breakthrough came with Steinkind (1979). The word denotes a foetus that has died in the womb and has been encapsulated like a little ‘stone child’. Its significance is broadened throughout the collection; the bewitched, that which is spellbound by a tremendous force, is just one possibility:

and this you will be

a child of stone,

a single sliver of you,

will be enough to fell a wild animal,

and everything will escape you

yes in vain the butterfly will settle on your

eyelids,

and your exhalation, your exhalation I will never

hear

As in the debut collection, the theme, which involves a linguistic complex of problems, unfolds in a number of role poems in which women’s voices speak: mothers with newborn children, Queen Kristina, the ‘frog-princess’, Sleeping Beauty (who awakens on a drip in intensive care), or Snow White – in the suite of poems by that name. She, too, is literally confined within her glass coffin, a sacrifice to men.

Opposed to the rational explanation of the world, which in the novel Det mörka alfabetet (1982; The Dark Alphabet) is proposed by a male psychiatrist with a cerebral stamp, is a psychotic woman who once met an angel and who knows – with Rainer Maria Rilke – that there are things no-one can comfort you about. Being chosen has stopped her short. Between these two extremes is the woman student of medicine who finally elects not to pursue psychiatry. The border between ill and well is far from being as clear-cut as the male spokesman of cerebrality would like to think.

The collection Akra (1983; Acra) sees an intensifying of the problems of the world and of language: a painful via negativa through barren landscapes and narrow mountain passes, where the words must let go of each others’ hands and squeeze through one by one in order to be ‘translated’. Gone is the lush and luxurious, in language just as in the setting: in Akra (1983; Acra) there is drought, depression, and disintegration, and a lack of connection and communication – with people and with God. And the God that the poetic speaker wrestles with possesses the frightening, averted, ‘dark’ power that is also seen in Lars Norén and Friedrich Hölderlin. The longing for God – the father, the lover – is furious. In ‘the waiting room’ between the holy and the profane, between life and death, ‘linguistic permission’ can be found; the poem is able to convey life, but can never generate it on its own.

Mary ”does not exist”, we are told in the first sentence of Samtal med en daimon (1986; Conversations with a Daemon). This strange little prose book, however, allows her to be born – within the framework of fiction. Here, too, it is a matter of a path into language, where different times, environments, languages, religions, and identities are examined in a longing for ‘conversion’ – the word corresponds to ‘translation’.

In the collection Kärleken till matematiken (1989; The Love of Mathematics), questions of this kind no longer seem to be as insistent, although they are still being addressed but in a cooler, more intellectual manner. What do I honour? Do I believe in the words? What does my religion look like? Can anybody convert from their own self? Where am I? Do I only exist in indignation, in a question? Eva Ström’s poems appear to speak more directly from her own experiences than previously; gone are the role poem and the lyrical monologues placed in the mouths of others.

With the novel Mats Ulfson (1991; Mats Ulfson), Eva Ström returns to the hospital environment that she previously employed in Samtal med en daimon. The no-longer young temporary doctor undertakes his first Caesarean, he assists at an abortion where the heart of the foetus only stops beating after repeated efforts, he is invited to the home of an older colleague, and reveals his previous career as an actor. But it is his inner reality that holds real substance and that brings liberation from all the emotional pressure the world places on him: his mother’s demands for love, his audience’s expectations, his experiences of failing, and the fear of losing himself.

There are many threads connecting this first novel (in the traditional sense) by Eva Ström to her previous oeuvre: the problem of identity and the questions of consciousness, perception, and world image, and their dependence on the linguistic codes we inherit. But there is a ray of light and liberation throughout the narrative, and as is also the case in Samtal med en daimon, the protagonist is returning to the world after a grieving process (literally from out of the womb of the church following his uncle’s funeral) – and is now prepared to break with the circumstances that cause him misery.

Like Walt Whitman, another of her literary idols, Bodil Malmsten wants to write her present and her participation in the lives of people. A frequent use of the ampersand and of capital letters signals an interest in American beat-poetry – a trait she shares with poets like Gunnar Harding – as does the deliberate use of the printed page’s typographical possibilities.

In the story of Mats Ulfson, language and aesthetic pleasure bring with them the possibility of freedom. In her latest collection of poems, Brandenburg (1993), Eva Ström lets visions from our present-day wars, a Europe in convulsions, tear through a painfully expanded consciousness. This is nothing less than the return of poetic criticism of the contemporary world, and it is no more suited to bringing comfort and confidence than was the case in the 1940s. It is salt and fire and must be so.

Crossing the Boundaries

Like that of a number of modern women writers, the work of Bodil Malmsten (born 1944) displays an obvious effort to transcend the boundaries of traditional genres, even those of different art forms. Her seemingly nimble (but certainly not facile) “B-ställningar” (Commissions) – texts for the stage and various mass media – have apparently disqualified her work in the eyes of the critics. Bodil Malmsten’s media image gets a recurrent mention in several interviews with her. It is not until the 1990s that the poet Malmsten is fully recognised as one of the most distinctive and characteristic writers of her generation.

Bodil Malmsten unites the image maker’s sense of the visual with a strong linguistic creativity, a joy in the possibilities of rhythm and sound and the shift in meaning of the words, in dizzying word-games that suddenly turn deadly serious. She successively develops her subtle intertextuality; the sounding box of language is at her command, from old hymns and penny ballads to Gunnar Ekelöf and Samuel Beckett. High and low is mixed in Bodil Malmsten’s synthesizer, quotes and allusions from pop culture as well as from fine arts sources. Here, one finds a sense of life split between city life’s artificial fascination and the call of the great wild otherwise known from rock music.

“Forget Dvärgen Gustaf (1977; Gustaf the Dwarf) – he never existed”, a provoked reviewer wrote about Bodil Malmsten’s debut collection in 1977. Her male protagonist is a power-seeker who swings the whip of society’s circus. Of course, dwarfs have been used before, as a symbol of evil, and both angels and dwarfs show up again in the work of contemporary authors like Eva Ström and Agneta Pleijel, but it is Bodil Malmsten who is accused of despising flaws and of the persecution of a minority.

After her debut collection, Dvärgen Gustaf (1977; Gustaf the Dwarf), follows Damen, det brinner! (1984; Lady, It’s Burning!), a ‘love-story’ told in the third person and played out against the backdrop of a canal, weeping willows, and a Tulo billboard. The protagonist, not quite young, is practising patience in more than one sense, but catches fire and starts up a relationship with a married man. The story is trivial and predictable, but it is controlled by a narrating authority that keeps the ‘story’ reined in. The futility of the present is set against the promises of absolute love held up by poets and opera composers.

Anna Maria Lenngren, see the article “From Parnassus to the Temple of Taste”.

In the poem “Döden 1986” (Death 1986), which introduces Paddan & branden (1987; The Toad & the Blight), the setting is familiar from the weather report:

Southern Norrland’s mountain districts & interiors

Forest clearings & mounds of stone, new land

Smallholders & grain & sheep

Half of what is sown will grow

The lambs were irradiated this year

As may be remembered, this was the year of the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl, but the personal disaster for the widower of the poem was even greater: his Stella, the star among stars, died of cancer:

High above route 81 the city shines

Like a diamond in the sky

The street lights along the Ovik mountains

In the gloomy TV-night

Glitter like Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue

With the jeweller Tiffany’s

THE WIDOWER can’t escape

Boy-drunk behind drawn kitchen curtains

Guzzling down yeasted dandelion wine

Bawling aimlessly & without voice

GIVE BACK STELLA’S BREAST

GIVE BACK HER HAIR

She would have been forty-six this year

Soon the young ewes will lamb

STELLA COME & HELP THEM NURSE

By the middle of this collection, Malmsten for the first time touches upon her frozen upbringing by foster parents in a Stockholm suburb, and in the short story collection Svartvita bilder, (1988; Black and White Images), she takes another step back and sketches childhood memories from Jämtland. The title poem in Paddan & branden thematises the class differences existing in the modern welfare state, whose hollowing and deconstruction Bodil Malmsten returns to in poems that reflect modern, alienated consciousness.

In the collection of poems Nåd & onåd, Idioternas bok (1989; Grace & Disgrace, The Book of Idiots), which is staged like a modern “Play about each of these little” people in a glass shopping mall, the narrator asks for the “greatest possible mercy”. Bodil Malmsten’s attention is turned to the problem of the good, and this is also what is at stake in her first novel, Den dagen kastanjerna slår ut är jag långt härifrån (1994; When the Chestnuts Bloom I’ll be Long Gone), in which the protagonist, the actor Maurice Lind, plays both the Prince – the character representing the light – and the dark Rogozhin in a dramatised version of Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot (1868). Bodil Malmsten dramatises an intense guilt problem and a possible reconciliation with life. There are close connections with the 1989 poetry collection Nåd & onåd, Idioternas bok, which ends in a full gospel of compassion and humanity. But in the new novel, which takes its motto from the Book of Job, the darkness is deeper, the existential gravity heavier than before, and grace is something that may possibly find its way into the world like light through rock.

Bodil Malmsten’s poetic method has become far more sophisticated. In the suite of poems Landet utan lov (1991; Land without Law), which is also part of the book of cuttings Det är ingen ordning på mina papper (1991; There is no Order to my Papers), the reader is lured into a linguistic world of rhythms and sounds, where the apparently carefree game is broken by sudden measures like unexpected line breaks and wild associations that urge pause and reflection.

She evokes a feeling of life that can be called tragic: around the burning present are just ashes and death, the vanity of vanity, and words written in sand. What remains, whether carved in stone or saved to a hard-drive? In this fashion, Bodil Malmsten approaches some of the most serious experiences a woman encounters, the inexorably striking: children that grow apart from us and leave us with empty embraces; not being able to have the children we long for; people we love who abandon us for others or for good. And ahead for all of us: the oncoming express train of death.

Nefertiti i Berlin (1990; Nefertiti in Berlin) was inspired by a weekend trip made by the poet and her adult daughter just before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Here the images are folded into each other: East and West; present-day self and the ‘adult kid’; Pharao Akhenaten’s beautiful queen, Nefertiti, with the daughter Maketaten on a relief from the 18th dynasty in Berlin’s Egyptian Museum; and the Egyptian scribe. And in her debut as a playwright – Den underbara bysten (1993; The Wonderful Bust) – Bodil Malmsten is back in Berlin. This tragic farce about a museum guard and a visiting woman is also about art and the one life we keep losing. Two people speak in absurd and lyrical monologues. Speech outside of and into time has always existed in Bodil Malmsten’s poetry, and the latest collection to date, Inte med den eld jag har nu. Dikt för annan dam (1993; Not with the Fire in Me Now. Poem for the Second Lady), was originally conceived as a play. It begins with something like stage directions given by an invisible narrator to whomever is about to make his or her entrance: a sunlit hotel room, where a TV set and a laptop computer add to the shimmer of light – and water – which is among the important leitmotifs of the collection. In this multilayered narrative poem, in which the present gathers the memory images of the past, the woman expresses herself in what is written: she is herself throughout her upbringing with her maternal grandparents and her cousin Stig, throughout her marriage, her barrenness, she is her experiences of loss, ageing, and death. The title of the collection has been borrowed from Samuel Beckett’s monologue Krapp’s Last Tape (1959). The fire opposes the leitmotif “DO NOT REMOVE STONES FROM BEACH”. The stones in their turn are connected with the motto from Ecclesiastes and Pete Seeger that to every thing there is a season; a time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together. The woman, whom we encounter again on the beach, literally walks between gravity and grace, between the insight that woman gives birth squatting over a grave and the equally strong conviction that the days of happiness are retained whether or not one is buried in sand to the chest: that the glowing moment is there, before we are extinguished. To conjure, to retain, in the words of the poem, the memory of the flicker of the sun-shadow, the pure and strong sensuality of water, the taste of the other:

“Perhaps my best years are gone […]. But I wouldn‘t want them back. Not with the fire in me now. No, I wouldn’t want them back […] not with the fire in me now”.

Translated by Marthe Seiden