What is my responsibility as a woman

Must I join the choir of wailing women

at the graves of men?

Will no one dare to cry out

when men come with the tramp of boots, with disdain:

‘what use your tears

what use your little cry?’

WHAT USE IS WAR

cry till only this cry exists

wrote the author and artist Ann Margret Dahlquist-Ljungberg (born 1915) in Att lära gamla hundar sitta (1962; Teaching Old Dogs New Tricks). Like a modern Lysistrata she speaks up, inspired by Elin Wägner’s Väckarklocka (1941; Eng. tr. Alarm Clock).

“All the hopes that women have held throughout the centuries of how to cheat themselves to a life, to survival, have revealed themselves to be treacherous. It doesn’t work without sex, like Lysistrata; nor with mutilation, like Hera; nor with innocently un-reflected escapes, like the woman of yesteryear. Nor to consciously slumber, like the women of today.”Ann Margret Dahlquist-Ljungberg: Att lära gamla hundar sitta (1962; Teaching Old Dogs New Tricks)“I see the young mother with her monstrosity, her handicapped and retarded child, as is the term. Like a mother of chickens she spreads her wings and wants to protect him, while she herself seeks protection within that stance.She might as well be me, perhaps she is me? But what options are there in a world where the protective resources are already condemned – and how will I protect the boy against me, against himself: against our ignorance and our indolence?”

(Ann Margret Dahlquist-Ljungberg: Att lära gamla hundar sitta)

The pain and anger in her voice has not been lessened by the destruction in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as depicted in the collection of poems Barnen i stenen (1983; The Children in the Stone). The intense fight against the war machine and the destructive effects of nuclear power which culminates here was already seen in Strålen (1985; The Ray), a nightmare vision in novel form opposing nuclear power. In Öppna brev till Olof Palme och därmed till oss själva – en antologi kring kärnkraftsproblemet (1974; Open Letters to Olof Palme and Thereby to Ourselves – An Anthology on the Problem of Nuclear Power), she lets a number of her contemporaries deliver facts and alternative solutions to the nuclear problem in various forms and shapes. She made another contribution with her book Homo Atomicus (1980). Her oeuvre’s defining mark of commitment and pessimism is underscored by her own illustrations.

Elisabet Hermodsson (born 1927) integrates several different art forms in her works. She writes about culture, participates in debates, composes music, is a ballad singer, an artist, an essayist, a novelist, and a poet. With polemic fervour she has defended the oppressed around the world, whether the third world population or women’s issues, the threatened environment or the right to violate established borders in the world of thought and art was at stake.

A guiding principle in her work is the responsibility of compassion: that the inter-connectedness of all human life must be recognised. She therefore criticises certain ‘objective’ scientific attitudes and questions them in her article “To name”: “Scientist, what do you want? What do you want with your definitions? Enclose, bind, state, observe. Observe without compassion. Enclose the living. Experiment with nature. Exploit nature.” (Ord i kvinnotid (1979; Words in the Time of Women)).

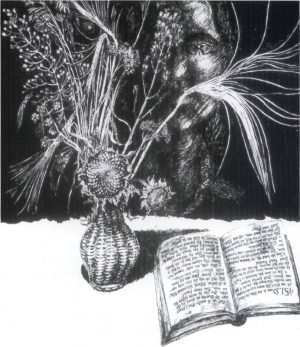

She considers the artistic task to be a ritual: showing the connection between idea and body. When her strange and distinctive picture poems, Dikt-ting (1966; Poem-Things), were published they, more than anything else in her later works, illustrated the passage in the Gospel According to John: “And the word became flesh”. At the time, she had for several years been working with the special kind of handwritten picture poems that she pioneered in Sweden.

For her, the ritual work of the artist carried an insight into taking responsibility for one’s fellow human beings. As a cultural critic and revolutionary Christian she participated in the cultural debate during the 1960s and 1970s. She was well-versed in the international discussion about Christian-Socialism, which can be seen in the poetry collections Mänskligt landskap orättvist fördelat (1968; Human Landscape Unfairly Distributed) and AB Svenskt själsliv (1970; Spiritual Life of Sweden, Inc.), and the oratorio Röster i mänskligt landskap (1969; Voices in a Human Landscape).

In the collection of ballads Vad gör vi med sommaren, kamrater? (1973; What Do We Do About Summer, Friends?), summer becomes the symbol of a limitlessness that cannot be tamed, and even prompts the ‘ideological belt’ to slacken. Sensually and attentively, she registers the changes in nature, but also its vulnerability to man, a theme that will continue to gain in strength in her later works.

Disa Nilsons visor. Visor om sommaren, samhället, mannen och universum (Disa Nilson’s Ballads. Ballads of Summer, Society, Man, and the Universe) was published in 1974, as a comic accompaniment to Birger Sjöberg’s Fridas bok. Småstadsvisor om Frida och naturen och döden och universum (1922; Frida’s Book. Small Town Ballads about Frida and Nature and Death and the Universe). Unlike many women from the world of the ballad, Disa acts as a female subject. She “wants to be contrary”, that is, act across political divides and be open as a human being and an artist to other attitudes and actions than those ingrained in and prescribed by society. She freely juggles the gender roles in Swedish society, but by increments a stronger consciousness of women’s roles emerges. She is somewhat influenced by, among others, Elin Wägner and Emilia Fogelklou, and like them she studies theories of former matriarchal societies, a subject explored in the collection of essays Ord i kvinnotid (1979; Words in the Time of Women).

In Gör dig synlig (1980; Make Yourself Visible), she searches for women’s language and lore, and finds values that women can identify with in theories and half-buried cultures. Not least of all she shines a light on the divine female element.

That we are worthy

of each other

has not been decided in a contest

To be worthy of each other

is what we in action

profess to each other –

love or hate

heaven or hell

Elisabeth Hermodsson: “Tema: kärlek” (Theme: Love) from Gör dig synlig (1980; Make Yourself Visible)

Man and woman

are both children

of a woman’s body

With the umbilical cord

tied to her offspring

Our mother subordinated

her mounds and wellsprings

and forests

even the man becomes

a carrier of peace

Elisabeth Hermodsson: “Jag äger min navel” (I Own My Navel) from Gör dig synlig

Yet another step towards the shaping of a new world view is taken in Stenar, skärvor, skikt av jord (1985; Stones, Rubble, Layers of Earth). She sees with terrible clarity the misuse of creation, but entreats nature to speak: “Stone remembers / what language forgot”. She seems to conquer an ancient knowledge about a betrayed and forgotten world whose divine nature has feminine traits. In the poem “Genesis” she shapes a new creation myth in which contemporary values are questioned. The conjuring voice is a woman’s; the tone is prophetic. The words of the woman become synonymous with the words of love.

In her latest collection of poems, Molnsteg (1994; Cloud Steps), Elisabet Hermodsson returns to her origins, where the romantic poet Hölderlin acts as a common denominator between the living writer and her dead German mother. She connects Hölderlin’s tragic fate with her roots in the mother’s city in the German region of Schwaben, where retarded people, ‘idiots’, were traditionally looked after. The romantic genius and the ‘least little brother’, the strong artistic passion and taking responsibility for one’s fellow human beings, are made visible alongside her own view of female identity.

The Bomb and the Baby

The Norwegian writer and psychologist Wera Sæther (born 1945) formally works somewhat differently than Elisabet Hermodsson and Ann Margret Dahlquist-Ljungberg, but her themes are similar. Working with mentally retarded people, she has found a connection with the weak and defenceless in society, and in the collection of poems Barnet, døden og dansen (1978; The Child, Death, and The Dance) she demonstrates a belief in God akin to that of Elisabet Hermodsson.

Wera Sæther reads like a dark continuation of Elisabet Hermodsson’s words to the scientist and his responsibility as creator towards his fellow human beings, and of Ann Margret Dahlquist-Ljungberg’s words about the nuclear bomb, when she in Sol over gode og onde (1985; Sun Over the Good and the Evil) writes about the conception of the nuclear bomb in 1945: “Then the Bomb was born and it was well-made. The scientists used birth and creator words. One of them exclaimed: Let there be light!”

Wera Sæther further develops the idea that military creation on the part of the man is his compensation for not being able to give birth: “In any case it is true to say that some men now, during the last forty years, have ‘given birth’ to their own ‘children’, without any woman. Just like a church has developed which exists within and outside of the normal churches, with nuclear weapons as cult objects, a generation of ‘children’ has also been developed. The first Bomb detonated at the ‘Trinity’ site was called a ‘baby’. When the scientific fathers of the Manhattan-project telegraphed President Truman after the ‘birth’ on 16 July 1945, the telegram read: ‘The child was well-shaped’. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima was called ‘Little Boy’. And today they are creating ‘fifth generation’ rockets.”

Can such a ‘civilisation’ ever be saved? Only with the language of love, Wera Sæther thinks, can evil be conquered and life worshipped – in place of death. In this striving, man and woman are not separated from each other: only by a united effort can powerlessness be conquered.

Translated by Marthe Seiden