“The Winter War of 1939 was raging. My work stood still; it felt totally unnecessary to try drawing pictures or painting. Perhaps it’s not so very strange that I suddenly had the desire to write something that would begin with ‘Once upon a time’”, writes Tove Jansson (1914-2001) in the Introduction to the 1991 edition of her first book, Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (1945; The Small Trolls and the Great Flood, Eng. tr. The Moomins and the Great Flood).

She finished the book in the late winter of 1944 when the war was at its height in Finland. Russian bombs were falling on Helsinki, and Jansson – who was already a noted artist – confided to her diary that she longed so much to get away that she “could burst”. That gloomy world of “ruins, ice, and searchlights” gave birth to the pacifist utopia of the family as a social system. But its peaceful surface is deceptive.

“As a political illustrator”, Boel Westin writes in her groundbreaking doctoral thesis Familjen i dalen (The Family in the Valley), “Tove Jansson moved easily between the domestic and international scenes: wartime rationing, the evacuation of Finnish children to Sweden […]”

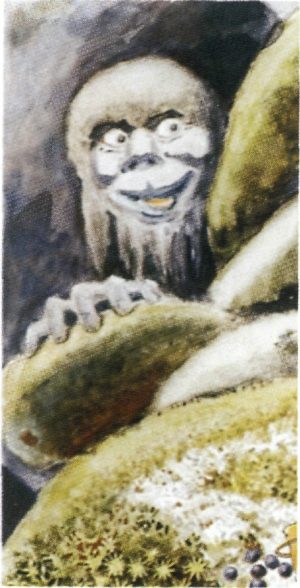

“A children’s book should contain a crossroads where the author stops and the child goes on”, wrote Jansson in a 1961 essay entitled “Den lömska barnboksförfattaren” (The Sly Children’s Author). “A threat or a splendour that is never explained. A face that never wholly reveals itself.” The mother-fixated Moomintroll in the picture book Hur gick det sen? Boken om Mymlan, Mumintrollet och Lilla My (1952; What Happened Then? The Book about Mymble, Moomintroll and Little My, Eng. tr. Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My) gets lost on his way home. Hur gick det sen? refers indirectly to Elsa Beskow’s picture book Tomtebobarnen (1910; Eng. tr. Children of the Forest) about an exclusive little brownie family consisting of a subservient mother, pretty daughters, plucky sons, and an autocratic patriarch. When Jansson’s mother would read the book to her as a bedtime story, she would scream in fright at every picture of the ugly mountain troll who peers out from behind the boulders and scares the wits out of the brownie children. Her mother taped a piece of paper over the malicious troll, but Tove pulled it off because she wanted to be frightened. Moominmamma in Hur gick det sen? assumes the same role as Beskow’s repulsive, sneering troll. She is the safe backdrop against which the entire adventure unfolds; in the final scene, she sits in sunny Moominvalley and cleans currants in Moominpappa’s hat.

The technique is typical of Jansson: a secure idyll that covers up a frightful abyss but always cracks eventually. The picture books Hur gick det sen? and Vem ska trösta Knyttet? (1958; Eng. tr. Who Will Comfort Toffle?: A Tale of Moomin Valley) outline the utopia that emerged from Jansson’s traumatic experience of the war’s meaninglessness, creating a Moomin world where maternal sensibility rules and family bonds extend to everyone. As Mooominmamma says so naively in Farlig Midsommar (1954; Dangerous Midsummer; Eng. tr. Moominsummer Madness): “How can they be so angry at each other when they are family?

The sneering Groke in Jansson’s subsequent picture book Vem ska trösta Knyttet? assumes the position of both Beskow’s troll and Moominmamma. All that’s left of Moominmamma are a few colours from the final scene of Hur gick det sen? Vem ska trösta Knyttet? tells the story of frightened little Toffle, who saves the even more petrified Grandpa Grumble, changing the world by virtue of his good deed. The final passage paraphrases Edith Södergran’s famous poem “Ingenting” (Nothing). Where Södergran writes, “Be calm, my child, for there is nothing / and all is as you see”, Jansson writes, “And Miffle knows and Toffle knows, that both have seen the end / of fear and fright and long, dark night, now each has found a friend.”

But Jansson’s writing does not end with the dream of a happy family. Her last Moomin books and adult fiction deconstruct this mythology.

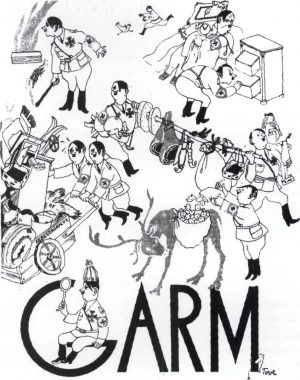

The Valley of Peace in the Shadow of War

The Moomin characters are progenies of a spindly and irascible little figure named Snork (Snot), which Jansson placed next to her name in her political cartoons starting in April 1943. Her parodies of Hitler, Stalin, and the war appeared in Garm, a liberal-conservative Finland-Swedish satirical magazine. Back in 1941, however, she had illustrated an article on the unconscious in the magazine Julen (Christmas) with a prototype that was a cross between a Hattifattener (a small, ghost-like creature), Groke (a hill-shaped outcast), and an emaciated Moomin. Moominmamma in Kometjakten (1946; The Hunt for the Comet, Eng. tr. Comet in Moominland) which was revised as Kometen kommer (1967; The Comet Is Coming), gave the Moomins their “pregnant” form while underpinning the story with an infantile, fantasised sexuality. Thus, the Moomin character originated both in anti-war protest and what Freud called eine andere Schauplatz (another scene), ruled by the logic of repressed material. The subtext of Jansson’s books is about this other scene.

The utopia of a peaceful society governed by the values of the good mother stems from the bankruptcy of masculine civilisation. The consequences of the war’s assaults on the civilian population, the severed family bonds, resonate like a minor key in the Moomin books. Policies of mass destruction are symbolised by natural disasters: floods, comets, volcanic eruptions.

Consistent with the allegorical tendencies of the time, the thin-nosed, ill-tempered Snork becomes the model for Jansson’s Moomin gallery in Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen. Moominmamma resembles a war widow who flees head over heels in search of a sanctuary for herself and her little boy. Meanwhile, Moominpappa has made off with the Hattifatteners, homeless deserters who “have no feelings at all.” Out in the great forest, Moomintroll and Moominmamma rescue an abandoned child, “the very small animal” that is called Sniff in the next book. The refugees have a collective hallucination of an artificial world where brooks run with milk and lemonade and bushes bloom with candy and chocolate. Finally, they are washed ashore to a refugee camp where “people from every corner of the world” are stranded. One of the displaced persons is Moominpappa, whom they find after having demonstrated the power of good deeds by saving victims of the war: a mama cat and her five kittens. In the spirit of the times, Moomintroll exclaims despite the absence of a papa cat: “A whole family! Mama, we have to save them!” Soon the sun is shining again, the flood recedes, and everyone moves into the Moominhouse.

Innumerable refugees and orphans take refuge in this valley of peace throughout the Moomin series: Sniff, Muskrat, the Hemulen, Snorkmaiden, Snork, Snufkin, Little My, Mymble, Thingumy, and Bob with their portmanteau and foreign jargon, Too-ticky, Fillyjonk, Grandpa Grumble, and other small creeping things.

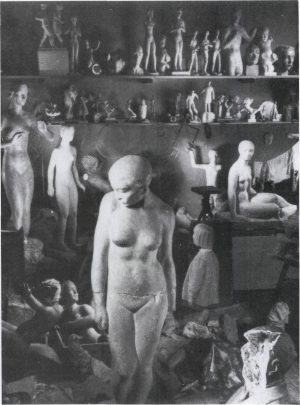

“How delightful that it was a girl”, wrote illustrator Signe Hammarsten-Jansson after the birth of Tove, her first child, in 1914. She called herself a suffragette and was a founder of the girl scouts in Finland. Bildhuggarens dotter (1968; Eng. tr. Sculptor’s Daughter), which is narrated by a young child, consists of episodic memories, satirical by virtue of their feigned guilelessness, particularly towards the melancholy father who loves animals “because they don’t contradict him. […] But it’s quite a different matter with Females.If you make statues of them they become women but as long as they remain Females things are difficult. They can’t even pose properly and they talk much too much.”

Kometjakten, the next book, is about a threat of devastation reminiscent of Hiroshima. Once again, solicitude for others averts disaster.

The apocalyptic streak in Jansson’s Moomin books stems from the Bible stories that her mother, the daughter of a pastor, liked to tell. They always began, “Once upon a time there was a little girl who was terribly pretty and her mummy liked her so awfully much.” But they were always about people who “long for their homeland, or who get lost and then find their way” or “about great storms that finally pass”. “My mother populated my childhood, turned it into a cornucopia of stories,” Jansson said in a 1952 interview.

Menacing Gender Difference

The Groke embodies the dark side of motherhood, adding greater nuance to its psychological aspects, in Trollkarlens hatt (1948; The Magician’s Hat; Eng. tr. Moomin and the Magic Hat). Meanwhile, the book introduces another important theme – that of difference. Jansson’s first curtseying male Hemulen, wearing his aunt’s lace gown, makes his appearance. Her technique is based on freezing the magical instant when neutrality transitions to gender difference, and the fateful decision between curtseying or bowing, wearing a skirt or trousers, must be made. Trollkarlens hatt signals a fundamental refusal to accept adult gender stereotypes and an attempt to replace them with an infantile, fantasised sexuality that resonates through the portrayal of male and female instincts in subsequent books. Towering above it all, however, is children’s desire to linger on the threshold at which sexuality is born in the form of infantile fantasies about where babies come from and speculation about the difference between mothers and fathers. The fact that all the Moomins have similar anatomies is a reassuring confirmation that no such difference exists. It resides outside the body in the magician’s enchanted hat that transforms everything into its opposite. Right at the beginning, Moomintroll is turned into a tarsier after hiding in a hat, which is the symbol of masculinity in the books. His corpulent figure grows thin, his short tail long, his small eyes and ears grotesquely enlarged, etc. Nobody except Moominmamma recognises him.

This portrayal of a deformed child, who can be affirmed as normal only by the tender and rehabilitating eyes of its mother, is a primeval scene. The perilous difference is postponed by a blessed maternal gaze. But Jansson’s adult fiction reveals the high price that this eternal, ostensibly harmonious, symbiosis exacts.

Jansson is also an incisive but unsung critic of masculine formalism and overspecialisation, not to mention male presumption as depicted in Muminpappans bravader skrivna av honom själv (1950; The Exploits of Moominpappa Written by Himself, Eng. tr. The Exploits of Moominpappa), Pappan och havet (1965; Papa and the Sea, Eng. tr. Moominpappa at Sea), and the autobiographical Bildhuggarens dotter (1968; Eng. tr. Sculptor’s Daughter), which acquaints the reader with her father Viktor Jansson. The title notwithstanding, the latter book is a tribute to her mother, who was the main, albeit unacknowledged, breadwinner in the family due to her diligence as an illustrator. The revised edition of Muminpappans bravader after Viktor Jansson’s death, Muminpappans memoarer (1967; Eng. tr. Moominpappa’s Memoirs), brought the male chauvinism of the Bohemian and melancholy protagonist into sharper focus.

The Moomin characters also appeared as cartoons, first in Ny Tid, a newspaper of the People’s Democratic Party, under the title of Mumintrollet och jordens undergång (1947-1948; The Moomin Troll and the End of the World). Jansson was contracted in 1954 to draw the Moomin comic strip for Evening News, which consumed most of her time for several years until her brother Lars took over. For a while, he came up with the ideas and she illustrated; a difficult proposition because he added what she called “masculine” objects like “machines and weapons and science fiction gadgets”. The paper ordered her not to criticise the government or portray sex. “Given the Moomins’ anatomy,” she quipped, “that would have been rather difficult in any case.”

Muminpappans bravader scathingly parodies the genre of male autobiography. “As a father of a family and owner of a house I look with sadness on the stormy youth I am about to describe. I feel a tremble of hesitation in my paw…” Unabashed masculine self-aggrandisement is on the march: “Geniuses are generally thought of as being rather unpleasant people, but I can’t say this has ever worried me.” Both Sniff and Snufkin are blessed with fathers during the course of the book, while their mothers are mentioned only in passing. According to the patriarchal genealogy, Moominmamma rolls in from the sea like a latter-day Aphrodite without a history of her own. The self-generating Mymble, a living advertisement for unreflecting motherhood, counterbalances the dominance of males in the colony that Moominpappa founds.

The Hattifatteners, a species of infantile vitalists who come to life when electrified, represent Moominpappa’s degenerate ways, which Moominmamma censures in Muminpappans bravader: “Cross out, cross out, cross out, his papa said. (But I had fun)”. The female equivalent of narcissistic promiscuity is Mymble, who has innumerable children (the verb form of her Swedish name is slang for copulate). Her daughter turns electric in Sent i november. “Mymbles want to be part of everything,” Moominpappa sighs in Muminpappans bravader, warning that they refuse to understand that nobody is interested in them.

In Farlig midsommar, the Moomins take refuge on a stage that has floated away during still another flood. Now that their house is underwater, the time for Moominmamma’s emancipation has apparently arrived: “‘I’m not washing any dishes today’, Moominmamma said hilariously. ‘Who knows, perhaps I’ll never wash dishes any more?’”

Settling the Score with the Great Mother

Trollvinter (1957; Troll Winter, Eng. tr. Moominland Midwinter) is generally viewed as the turning point in Jansson’s evolution towards adult fiction. It possesses features of a depth psychological coming-of-age novel. Moomintroll triumphs over winter on his own while the rest of the family blithely hibernates. The illustrations depict moods and emotions instead of concrete events, culminating in a melancholy atmosphere of farewell. Moomintroll meets Too-ticky, a stern lady in a sweater and trousers, who teaches him that snow works more or less like a magician’s hat: “You believe it’s cold, but if you build yourself a snowhouse, it’s warm. You believe it’s white, but sometimes it’s pink and sometimes it’s blue. It can be softer than anything and it can be harder than rock. Nothing’s certain.” It can also be the murderous Lady of the Cold.

Pappan och havet, the next book, traces Moomintroll’s ongoing development towards adolescence. He finds himself in cahoots with the Groke, who differs from Moominmamma in that she loves nobody and is cold as can be, which fits right in with his attitude towards his own family, which in this book resembles an ordinary, complicated nuclear family. Bored to death, Moominpappa decides to play the patriarch and force Moominmamma, who roams around her beloved valley “feeling alive”, into exile on a barren island.Thus, the book leaves the Moomin idyll free to nurture the “other scene”, which is exactly what happens in Sent i November (1970; Late in November; Eng. tr. Moominvalley in November), whose working title was “Paradise Abandoned”.

Written shortly after the death of Jansson’s mother, the book is decidedly a metanovel about an idealised and idealising mythology. She takes final leave of the social utopia that the family had previously represented. The protagonist is the shy little whomper Toft that, longing for a mother “who cares for you”, tries to recreate the Moomin idyll as a bedtime story. One day, however, “everything goes backwards” and Toft embarks on a pilgrimage to Moominvalley, where the family is nowhere to be seen. Moominhouse is bursting with other supplicants – Fillyjonk, the Hemulen, Snufkin, Mymble, and Grandpa Grumble – and is starting to resemble a therapy centre where most everyone comes to terms with their need of the Moomins and learns to assume responsibility for their own lives.

Nevertheless, the narrative returns to its source, a Nummulite, which turns out to be a sign that points to, diminishes, and depletes the charged image of Moominmamma. Toft, who bears a striking resemblance to Jansson in real life, stages a bona fide exorcism. He gets his hands on a book that the Moomins had hidden in the attic. It is all about a little Nummulite on the sea-floor that developed into “a deviant” at the beginning of time, was “increasingly unlike its relatives” and ultimately resembled “nothing other than itself”. Thus, the Moomins have incubated a story of something that is different and must therefore go its own way.

This curious hybrid of Moomintroll and Hattifattener for whom “electric charge” is a necessity of life invades Toft’s imagination and gradually takes over the function of the Moomin idyll in his consciousness. The deviant’s contact with undercurrents lends him magical creative power as well as a secret life, a narrative to hide in. “‘It’s my thunderstorm’, Toft thought. ‘I did it. At last I can describe things for myself so that they can actually be seen. I shall describe things for the last Nummulite […]. I can make thunder roll and lightning flash, I am a Toft whom nobody knows anything about.’”

Electricity and thunderstorms are associated with erotic tension in Jansson’s adult fiction as well, Barbro K. Gustafsson argues in her doctoral thesis Stenåker och ängsmark – Erotiska och homosexuella skildringar i Tove Janssons senare litteratur (1993; Stone Field and Meadowland: Erotic Motifs and Homosexual Depictions in Tove Jansson’s Late Literature).

The Deadly Truth of Art

A pervasive theme in Jansson’s adult fiction is the ethical conflict that arises when the desire to create art “in maternal tenderness” risks harming others. Aunt Gerda, a spinster and the protagonist of the title story in Jansson’s first book for adults, Lyssnerskan (1971; The Listener), creates forbidden art when she decides to use the explosive knowledge that she has accumulated through the years as the family’s confidante. She draws a family tree with crayons so that all the secret, perverse relationships glow like “big pink sheaves”. For the first time in her life, she experiences “the bittersweet feeling of power” when she makes contact with “her own secret opinion, which wasn’t completely benevolent.” Manda, the clairvoyant embroideress from the Österbotten region in “Grå duchesse” (Grey Duchess), can no longer create after she silences an inner voice that keeps urging her to reveal the names of people who are about to die. Truth-telling in art is a deadly venture, as opposed to Moominmamma’s project of building a society in which everybody is one big, happy family. An artist is inevitably a solitary deviant, like Snufkin the nomad in the earlier Moomin books or Toft the whomper in the last one.

If the autocratic, threatening side of maternal tenderness is to lose its grip, biological motherhood must be held at arm’s length, as in the masterful novel Sommarboken (Eng. tr. The Summer Book), which describes the relationship that evolves on a primitive island between a woman with a weak heart and a granddaughter who has lost her mother. The theme alternates between the desire for solitude and the responsibility for others. In reality, the grandmother is too old and sickly to take care of a grandchild in crisis, but they find one another anyway, each on her own terms. Sommarboken can be read as a retreat from the attack on the good mother that Jansson had mounted two years earlier in Sent i november.

Jansson’s unique contribution to the tradition of literature by women that conceals sexuality is a kind of sublimation that engenders a narrative. The method is discussed in her adult fiction, which posits a fundamental link between maternal tenderness and erotic tension. The primeval scene in Trollkarlens hatt, where Moomintroll is transformed back from a tarsier by his mother’s gaze, reappears in a more nuanced form in “Den stora resan” (The Great Journey) from Dockskåpet och andra berättelser (1978; The Doll’s House and Other Stories). The price of symbiosis is high. A woman dares not have a lesbian relationship for fear of betraying her mother, whom she lives with and calls “her beloved.” They are wont to play an old game called “Have you been abandoned in the woods?” according to which the mother consolingly caresses the neck of her daughter, who presses “her face to her mother’s throat, as close as she can get” and repeats: “Yes, I have been abandoned in the woods.”

The story ends with the words, “Some queens rule for a very long time.” Jansson’s mother died in 1970, the same year she wrote Sent i november, in which Toft overthrows Moominmamma’s inner regency, cuts the umbilical cord, establishes the difference between them, and expels the dream of symbiosis. “Every time he thought about Moominmamma, he would get a headache. She had grown so whole and gentle and comforting that it was unbearable, a big, smooth, faceless balloon. All of Moominvalley had become unreal; the house and garden and river were nothing more than a play of screens and shadows, and he didn’t know what was true and what was simply his imagination. He had waited for a long time and now he was mad.”

In his anger he heads out to the forest and suddenly finds himself in back of Moominhouse, where Mymble had said that the Moomins went when they were annoyed and sick of each other, hardly a state of affairs that had existed before Pappan och havet. Everyone had walked around the ugly and rejected “forest of rage” with “dark thoughts”. “He grew quite calm and very attentive. With enormous relief the worried Toft felt all his pictures disappear. His descriptions of the Valley and the Happy Family faded and slipped away. Moominmamma glided away and became remote, an impersonal picture, he didn’t even know what she looked like.” The painful process of separation, the postponement of which had threaded its way through the Moomin books since the primeval scene at the beginning of Trollkarlens hatt, is now in its final stages. Maternal tenderness changes place, occupies Toft and inspires him to conceive a story about a “new mama”, a wholly ordinary person who can be both happy and sad, and who is capable of being helped. He is no longer abandoned in the woods.

Translated by Ken Schubert