The works of Stina Aronson (1892-1956) live and breathe under the constant threat that the personal (the other) language, her personal experience of the self and the world, will be “strangled with the soul’s fingers”. She seems to be obsessed by the prospect of being literally talked to death, like the victim in her play Dockdans (1928; A Doll’s Dance):

Kurt: The horrible thing about it is that I also killed her another way, besides sending her into the jaws of danger. Intellectually. I strangled her with the soul’s fingers. Listen to me, I wanted it to happen. I did it in cold blood. I overwhelmed her with my heartless proof the moment we started talking about something. It didn’t matter what it was. She wanted to be cautious – I pounded her with evidence. Pound, pound.

Lady (shivering): You… hit her… ?

Kurt: Certainly not. Never. I simply murdered her.

Aronson, who published seventeen books, is best known for her depictions of life in the ‘wasteland’ of Norrbotten province. She acquired a wide readership with her novel Hitom himlen (1946; This Side of Heaven) after many years of a distinguished writing career.

Norrbotten became her destiny in 1919, the year she and her husband moved north to the Sandträsk Sanatorium where he had been hired as medical superintendent. She devised bold plans for herself as a farmer’s wife surrounded by a troop of fosterlings. But those dreams came to naught. Being a doctor’s wife had an immediate claustrophobic effect on a woman who was spiritually and intellectually thirsty, far from the maternal or pragmatic manager of a typical agrarian household. She suffered from the isolation and deafening silence, and it was a long time before she could write about the wasteland.

Aronson was the daughter of a student, later a bishop, and a maidservant, and was boarded out as a young child. The wound of illegitimacy never stopped hurting, but her gender was her biggest stumbling block, which she ultimately overcame as an author. The wasteland of her later works serves as liberating territory north of the Law where the ‘other’ language can be realised. It is a world composed of differences – people are allowed to be themselves – but not differences between the sexes.

“I wander about, you know, like an aimless ship that never stops honking its foghorn”, she wrote to her sister in March 1920 during one of her endless hours of desperation. “I stand in the kitchen, the mist veils the shore, and the horn blasts away inside of me.”

Rather than the “prophetess of home and the family” she had anticipated before arriving, Aronson found herself turning into an author. After publishing three traditional narrative novels in as many years – En bok om goda grannar (1921; A Book about Good Neighbours), Slumpens myndling (1922; The Ward of Coincidence), and Jag ger vika (1923; I Give In) – she fell silent, only to return as a modernist experimenter during her short but intensive middle period.

Her fiction of the late 1920s and early 1930s represented a new start. Her foghorn boomed again – this time at the danger of being tangled up in a net of words. Två herrar blev nöjda (1928; Two Gentlemen Were Satisfied) constitutes a radical break with her earlier approach. Not only does familiar narrative yield to a fragmentary, elliptical style, but the theme of adultery highlights the departure from tradition. The cry of the protagonist’s lover lures her away from the security of hearth and home onto the highway of life. “Bit by bit, I began to hear the great chorus of the wolves. I saw the wanderers. The sky was all of one piece, no longer lacerated by leaves […] The advance guard of my preconceptions collapsed and I had to walk over their dying corpses, onward, onward […]” – Feberboken (1931, The Fever Book), her seminal work of experimentation and rebellion. The highway, the urge to ramble and roam, is a metaphor for the creative instinct. During this period, the cry of a lover is the only thing that can arm the author with the will to brave the hazardous, unchartered territory of writing.

Feberboken is her only real love story, as well as her most intense work on the level of both style and substance, betraying profound questioning and ambivalence. The relationship is never consummated. The book is the tale of a conversation/sexual encounter that never happens.

Reality is split down the middle. There are two ways of speaking, two ways of thinking – an ‘overview’ and an ‘inside view’ of the self and the world, as Emilia Fogelklou would have it. Worldviews and the concrete use of words begin to merge with each other. “I like to juggle them, the words,” Mimmi writes in Feberboken, “test their power, put them in my pocket, conjure them up, perform tricks. And when Hugo’s perfect, ferocious serves come my way, I can’t always return them. Everything falls apart.” She experiences the anxiety of divided language, Aronson’s crown of thorns – as expressed in its most threatening and polarised form by her two plays. The heroine of Syskonbädd (1931; The Children’s Bed) is committed to a mental institution by her husband, while the protagonist of Dockdans dies – in both cases due to their ‘feminine’ mode of expression.

Medaljen över Jenny (1935; The Medal in Honour of Jenny), which won an award for ‘working-class novels’, is the only book she wrote that tries out concepts of female solidarity inspired by Elisabeth Tamm’s school in Fogelstad. Jenny is a needlework instructor who “has made a silent but firm commitment” to leave behind not only a little dust, but a building – a seamstress collective – after her death. A subtle novel of emancipation, it questions whether marriage is necessarily a happy ending.

At one level, Aronson’s entire oeuvre revolves around the question of whether the other language (worldview) is to die or be left alone. Until her narratives of the wasteland come along and provide a kind of release, her writing is an excruciating battle between “holy ineffability”, “life itself”, and the brutal dictates of words.

“You have a name, silent bird, / your name is my beloved conjecture” – the last lines of a poem in Tolv hav (1930; Twelve Oceans). “Stumhet” (Muteness) in Kantele (1949; Kantele) puts it this way: “But the country of the soul is a huge expanse / that no words can contain. / For the fleeting language of the tongue / uses words of love and warfare. / But to open the mine shaft of intuition / lips must close and fall silent.” Kantele never casts doubt on intuition as a source of knowledge – the long, costly tale of muteness. But Tolv hav exposes a gap between perception and language.

Many of Aronson’s heroes and heroines speak uncertainly, tentatively, quizzically. Their quest, an impatience to speak and be heard, vibrates with a powerful sense of yearning. The pursuit is for the other, an interlocutor – a common mode of conversation. But something else is also looking for the right words. It as though the only chance for her vulnerable characters is that indefinite speech, an ‘open’ language that injures and branches off, that be constantly incorporated into ‘the one and only’ that is never constrained by precision, that never ends.

Primitivism for Aronson centres on Artur Lundkvist, their love and friendship in 1929 and 1930. He was the model for the beloved poet Hugo in Feberboken and – more loosely – for the lover in Syskonbädd. What may appear to be affected intellectualism in the spirit of the times has more to do with remarkably concrete, down-to-earth experience that is evident from the beginning of Aronson’s career, long before primitivism saw the light of day. Depriving the material world of its existence abruptly merges and becomes synonymous with robbing human beings of their immediacy and spontaneity, life as it is actually lived.

Mimmi is plagued by her overeducated ego and drawn to Hugo’s, which is “delightfully unrefined.” She may be scared to death, but she yearns for the intoxication of love and madness: “I wish I could become a melody in order to attain it”.

The fever is the dynamite that will break open the shell of ego and form.

“I have a love for him, a wild desire …” is the last line of a key scene in Feberboken. The object of that love is not Hugo, as might be expected. It is a poor lunatic whom she catches sight of from a café on Boulevard de Sébastopol when she goes to visit Hugo.

“The man excited, fascinated me. I had an insane urge to own him, inhabit his world, be crazy about him […]. I thought he gave me a glimpse of the way […]. What accursed eyes – light poured out of them. With eyes like that, I could finally conquer form, see and crush at the same time. And be crushed.”

Hugo, her muse and lover, calls to her from the highway of life. But the lunatic is the highway itself, the world she wants to inhabit and participate in. Although threatening, the “inebriation of madness” in Mimmi’s hungry imagination becomes the creative force that will liberate the “melody” while shattering both the ego and the book’s compulsively cohesive, overly disciplined form. In Feberboken, the Dionysean flow of healing creativity materialises as out of a dream, conjuring up a new role for authors.

“Explain to me, darling … explain … explain … How can it be that way […]?” Aronson’s heroes and heroines try to unfetter established discourse by adopting a sceptical attitude, as if creating latitude for emotion, the desire for a heterosexual encounter, a heterological conversation.

Marianne Hörnström

Chronicle of the Wasteland

The novels Hitom himlen and Den fjärde vägen (1950; The Fourth Way), along with the short story collections Sång till Polstjärnan (1948; Ode to the North Star) and Sanningslandet (1948; Country of Truth), create a domicile for Aronson’s narratives.

The writer in Feberboken dreams of “an encounter in territory that has not yet been paved or plundered.” Now the ‘wasteland’ of northern Sweden turns into a place that can make room for the ‘other’ language of intuition and silence, a world that branches out towards that which is prior to or beyond the petrification of words.

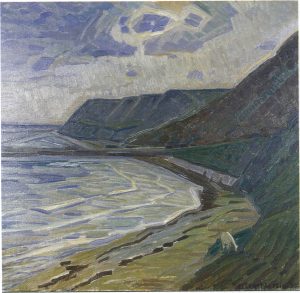

Hitom himlen, which brought her popularity for the first time, is about the inhabitants of a far, poverty-stricken corner of northern Sweden. Emma Niskanpää, a gentle and peaceful woman, lives with her husband and somewhat backward son (“my John”) on an isolated farm. More important than the individual characters is the setting: sparsely populated, quiet, overpowering – solitary farms, mountains, lakes, distant hayfields. People live far apart and their encounters are charged: “the mysterious act of approach”.

Aronson’s modernist project unveils the countenance of this world beneath empty phrases and hopelessly intertwined words. Rather like an archaeologist, she digs painstakingly for that which is virtually unknown.

Most of the characters who inhabit her wasteland are women, living their everyday lives. Their existence has two different trajectories: the sheltered, peaceful realm of daily chores and a timeless, archaic world where the boundaries between the body and the environment have faded, where everything coexists in a soothing, sometimes stifling, warmth reminiscent of the womb. Hitom himlen describes the communion of these virtuous women:

“Their clothing smelled of ashes and milk even when they were outdoors. It was no different with their daughters. Like a circle under their bare feet, the shadow was brown as if they were standing on a wooden platform […]. Their pores absorbed the day’s unappeasable appeasement. The earth beneath them was as warm as a body.”

This world is also archaic in the sense that time stands still. “An enormous, ring-shaped expanse carelessly surrounded by the horizon […]. Its eternal hallmark was immobility.” (Sång till Polstjärnan).

Every being, object, or phenomenon – Emma Niskanpää, a storm, the darkness, the farmer’s son who ploughs the rain-drenched fields, a fox – captured by the lens of the narrative becomes the hero of the moment. The narrator does not establish a hierarchy of that which is seen and heard. Aronson’s wasteland encompasses everyone and everything. Old verbal structures dissolve in favour of a previous order. The narrative opens with the same sense of immediacy towards the surrounding world, embracing light, darkness, wind, the swaying of a tree, the odours that a dog smells, the sound of a fox, the sight of two magpies jumping about.

The radical absence of hierarchy creates an ambivalent mood. An idyllic atmosphere, the comfort of being enclosed in the circle of an archaic world, reigns.

But spontaneous, defensive gestures interpose – the observer is suddenly unsure of everything, as in Sång till Polstjärnan:

“She shuddered […]. As she righted herself, her features altered in some indefinite way […]. And anyone who saw her would have had to say: this woman was young only a minute ago, but no longer. As if fate had played a practical joke on her.”

The shudder constantly recurs, establishing a powerful presence through sudden identification of horror and its possibilities:

“The old woman and child were still sleeping. Their heads lay right next to each other on the pillow, as if sealed within the same chamber, so different and yet a living entity. A murderer could have slit both of their throats with a single gesture.”

(Sång till Polstjärnan).

Hitom himlen begins and ends with the world of mothers, children, and their language, from which Aronson derives the authority for her singular, innovative, and modernistic story-telling technique.

It is as though the narrative voice is enveloped by a mother’s soothing body, whose pores inhale the birds, dogs, grass, and human beings that impinge on them.

At the same time, the prisoner of this body seems anxious to push it away. The feeling of security is accompanied by an anxiety-ridden apprehension of suffocating symbiosis.

Among the innovative features of Aronson’s tales from northern Sweden is the paucity of plot in the generally accepted sense of the word. Discovery of the world, its serenity and sudden horror, is the primary event.

Traditional narratives occasionally peep out like stones that have been paved over, but they are transformed to something new. Romantic love is refashioned into a story of devotion between Emma Niskanpää and her son.

Early male modernists in Sweden were passionate about portraying women as elemental and primitive. In their ossified state, such female characters served as a pillar of their writing.

The heroine of Feberboken fantasises that she is standing in a river. The water playfully lifts her breasts until they float on the surface like a pair of bell buoys – the same life-affirming image as the one on which the male authors constructed their poetic worlds.

But the female author checks herself. “When I tried to make out the river from the bridge, a wispy cloud drifted by and made the water illegible.” She is unable to decipher the code that the avant-garde of the time used in depicting women. The image has to be erased.

Only then can the ‘wasteland’ of northern Sweden become a venue for lending a body and voice to that which has shrivelled into a symbol. Emma Niskanpää “had a mild, blank expression on her face. It was like writing that had been scratched out”. The “elemental woman” is not the object of desire, but the deserted place where a new narrative can begin.

But certainly not completely deserted? The greatest inner tension in Aronson’s later works is between the modernist description of the world and a moral or ethical attitude towards it.

Sång till Polstjärnan speaks of the “gift of resonance, a latent echo chamber that may be the ultimate form of compassion.”

Aronson’s stories of northern Sweden offer the gift of resonance that transforms alien silence into familiar intimacy, which somehow remains fundamentally unknown and unknowable. “As if fate had played a practical joke”.

Aronson’s tales of northern Sweden combine ethnographically correct portrayals of everyday life in the ‘wasteland’ with descriptions of a dreamlike landscape where love is a “two-headed body”. And what is there beyond the body – “a man’s empty suit”? The narrator cannot know. Hence the radically revised, perforated, and equivocal stories.

Eva Adolfsson

Translated by Ken Schubert