In the early 1950s one of the great Swedish authors made her debut with a dream-like fragmented book about three young girls. It was the young Birgitta Trotzig (born 1929) who published Ur de älskandes liv (1951; Out of the Lives of Lovers). Its initial statement is: “As a child Aimée was always hungry.” In this book, the hunger becomes a striving to reach beyond the limitations of the I, to reach the You that is indispensable to life – this will remain the basic theme and stylistic movement of Trotzig’s works.

Ur de älskandes liv (1951; Out of the Lives of Lovers) tells of choosing artistic identity in order to write this desire for the other. Primarily, it is about breaking free of the aestheticised woman’s prison. Initially, the young woman in the narrative seems to melt seamlessly into the female space that surrounds her. But within the narcissistic enclosure lurks petrification, which the girl sees in the image of the mother: “the mother in front of the mirror […] immobile like a stone.”

The girl is taken beyond a limit where the confined self can be resolved. A biological process – sexuality bursts forth: “the hairy triangle of the sex: as if a shaggy dark parasitic animal had sucked on to her lap and starved on her blood.” Set against the image of the confined woman’s silk cocoon is the vision of bodies that open, that crack: “as if a disease gnawed itself out from inside them” – a different sort of femininity than in the sheltered room. And self meets world in the regions of literary modernity: in a vision of the city of Paris’s masses of houses and floods of people.

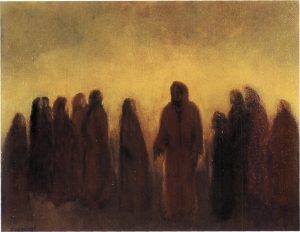

Birgitta Trotzig’s second book Bilder (1954; Images), a collection of lyrical prose sketches, pens a different aesthetic basis for the works – reduction, shelling. Through the prose poetic world of alienated physicality and primeval silence a Christian mysticism speaks, centred within the wounded body and employing the traditional imagery of mysticism: the rose on the tree of life, the rose that is a wound. A language that, in the spirit of modernism, simultaneously expresses an immediate and bodily existence. “The Wound: a slab of tepid slimy flesh.”

With De utsatta (1957; The Exposed), which has the subtitle “A legend”, the Trotzig narrative world gains its basic traits – it is a world lacerated by violence and the war. In the 1950s and early 1960s, a time dominated by Cold War ideologies and the construction of the Swedish welfare state, Birgitta Trotzig introduces something different: a landscape of death and destruction that demands to be seen.

“I was born in 1929. As historical perspective, that means: the basis for everything, the great emotional approximate value, the basic experience that determines all the coming values and evaluations is that which is called ‘the war’ – the total darkness, the total injustice that comprised the Jewish park benches in the Germany of the 1930s, the torture, the extermination camps, the occupations, the bombardments, the refugees. The great tradition of destruction.”

Hållpunkter (1975; Fixed Points)

De utsatta begins in near-emptiness: “– in no direction did the eye meet any resistance.” Out of this nothing is created, as though birthed out of a sea, a town in the “Province of Scania” in “the time of misfortune”, the war between Denmark and Sweden during the late seventeenth century. Within the historical material, a religious complex concerning the absence of God and an existential complex concerning “human loneliness between walls, inside the body” take shape.

De utsatta chisels out a theme that will be further developed throughout the works: a strife between two world views, where one is connected to the birthing body, the child, the life on the edge, and the other is tied to the limiting law, the religious and societal order of power.

The protagonist of the tale, the parson Isak Graa, is longing and hungering, while also an administrator of the punishing patriarchal religion he has inherited from his fathers, those who “knew that the child, like the woman is of nature, and that nature is evil”. He collects a treasure of righteousness for the Lord: “the word of the law has been preached and the writ of the word exacted on holy days as well as everyday.”

Only when this parson has been driven into the uttermost vulnerability and denigration does the narrative allow him to reach liberation. There is a transformation within himself, but also within the narrative, which reaches a lyrical climax in the hymns of transformation. The legal father steps out of the crushed shell of the ego and meets the other – the suffering Christ embodied by Isak’s daughter, the renounced child, the renounced woman: “Now I bend below your eye-bow’s low vault of bone, now I enter into the narrow circle of your blood; now your pain is mine to crush me, now your fear is mine to dissolve me.” “In you I am arisen.”

Birgitta Trotzig’s narratives are related to genres such as legends, the biblical parables, the lament, the hymn – but almost always in such a way that the older original is ‘soiled’. The legend of Isak Graa rewrites the Passion of the Christ, and in so doing strips it of all notions of beauty in suffering. The pitiful Isak Graa is depicted in painful detail as he is forced to become part of the “begging animal”, then one of those chained in the “loony bin”. Here, among the wounded, the crucified Christ lives: “his body’s hour of death was in them.” In “a strange body; a barely working, gasping, worn out, broken, soiled vessel: shattered, soiled, warped; crying; ready to burst from impurity, dead matter.” From this low position upwards movement, towards extolling the earthly living, can commence, as when Isak Graa finally sees the daughter:

“And her face expired the breath of fire like a dew; like a fruit her skin was full of fresh sweetness; the sweet blood pulsed and scented through its yielding heat; and it was the face of a living.

A temple she was, an altar and a song of praise: the ugly one.”

The Speech of Pregnancy

Lyrical prose is a basic form in Birgitta Trotzig’s works. It grows from a ‘female’ sphere of motifs: watching the tender infant in Bilder. In Ett landskap (1959; A Landscape), subtitled “diary – fragment 54–58”, a woman’s pregnancy becomes the point of departure for reflections on art and life – it is a woman living in Paris, the home of modernist creation. Ett landskap formulates the thought – and the desire! – of the Author’s death: “Language: establishing a relationship with reality. Entering into a relationship with reality – to pass into it, to be crushed, crushed to a sludge, to disappear and keep on disappearing.”

Birgitta Trotzig’s Sammanhang – material (1996; Connection – Matter) unites once more a list of different styles, taken from lyrical prose, the language of vision, or that of prayer. The subtitle “Matter” points to the connections of language with the material world, with the stone and the shard, with the yet-unformed person: “back to child; to stone; to nothing – no-thing.”

In Ett landskap, the crushing of the ego is irretrievably connected to giving birth. A sort of speech of the pregnant is created that carries the insight that the reality of woman who gives birth is “to die so that another may live”. In this process of giving birth and dying there is the option of uniting with the other: in the sacrifice of the self, in the dispensing of love. The loving and needing human being is reflected in something akin to the birthing woman’s body; in a confirmation of its vulnerability, which continually breaks up the borders of the ego:

“Central in my life is the gaping wound. A flaw. And what a flaw! The deep, exposed hunger.

“At the least movement it breaks open and I bleed uncontrollably, uncontrollably, impossible to hide – anyone can look inside me, I am just an opened body.”

In Ett landskap (1959; A Landscape), the modern work life is criticised from the ideal of love. The organisation and hierarchy of work must be “in the name of the reasonable, meekness, and with care of that which is living and growing under your command”. An ethic of solicitude that is suggested in connection with Simone Weil’s expositions about work – in the Swedish tradition there is an antecedent in Ellen Key’s writings about the work of love.

The centre of the Paris imagery is the church that is a womb: “Notre Dame, the darkness of a vaulted womb. The stone cavern, the man cave existing in birthing”. The speech of the pregnant takes us into an existence where place and event, space and process cannot be separated. A “human cave” “existing in birthing” – what is inner, what is outer? The different ways of existing are intertwined. The border between self and world, between ‘culture’ and ‘nature’, is dissolved.

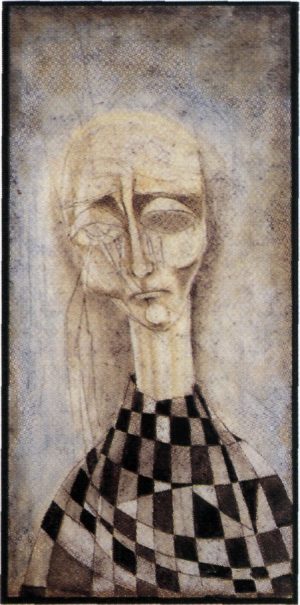

The speech of the pregnant is connected to the modernist criticism of meaning, of art as representation. Art becomes objectified, corporeal, perhaps most obviously in the collection Ordgränser (1968; Word Borders), a lyrical prose contemplation of the conditions of art. In fragments, it depicts some ragged vulnerable people – and old Russian painter in Paris, a lost poet in Tuscany or in Prague. Through their stories the writer searches for the living word – a word that can break through the contemporary cacophony of “formulas, slogans, definitions”, everything that hides the uttermost pain of living.

The last fragment in the book addresses a suffering fellow creature – it could have been a beautiful and touching conclusion: “You my broken-down fellow-man.” But it is about a human being “on the hard island, locked inside a metal cage”, transformed to “a screaming incomprehensible mass in which rages the extinction of every living thing.” A human beyond any possible narrative: “Time runs blind and mute through you, who can ever know anything real about this.” The final words, addressed to a divine you – “[t]his you have thrown onto the scales for our redress” – stand like a mockery and yet also as a paradox of acceptance. Just as the text in Ordgränser is the continued breakdown of narrative – “how could it be conveyed”? – while also being a continued striving towards the living language, which perhaps only exists at that border where “rages the extinction of every living thing”.

Throughout her literary career, Birgitta Trotzig remains active as an intellectual. In Utkast och förslag (1962; Drafts and Suggestions), she contemplates the role of the artist in modern society. Jaget och världen (1977; Self and World) discusses the modernist tradition of “questioning, kicking out of the driver’s seat. Counterimage, counterlanguage.” Here, her own writings are analysed as well: “I work with a sort of lyrical prose-poetry – so to say work in an eternally retarded moment of linguistic creation. / […] / experience the difficulty of language as a sort of existential condition: one is continually at the beginning of language and without pause experiences how threatened it is.” The eye is turned to the necessity for dialogue: “poetry cannot naively take a silent stone out of nature. It will always be fighting what the words have already been used for. Its kingdom is upkept in continued battle with the acquired and inherited meanings.”

Between Birth and Death

In the essay “Hållpunkter, hösten 1975” (“Fixed Points, Autumn 1975”) Birgitta Trotzig writes: “The great problem is terribly simple. A brief run between birth and death. That human life should be a community of love. Why doesn’t this exist?” This attention to the progression of life as a whole is found in all her stories. En berättelse från kusten (1961; A Tale from the Coast) begins: “On Good Friday almost four long decades before the turn of the century 1500 a girl child was born in Åhus” – and it ends with the death of the girl: “And she was lowered into the sea and was gone.”

If De utsatta followed the man of law, En berättelse från kusten moves closer to the other polarity of the Trotzig landscape of humanity: the birthing woman. In this chronicle-like tale, the loss of a mother glimmers time and again like a sharp shard. Where is she who should lessen the suffering of humankind? Not in the mother figures of official religion: “Their laughter was too sweet.” Something other than this sweetness is lifted out in swift flashes: an amulet found on a battlefield across the Baltic Sea, “the likeness of a mother with the face almost rubbed away” – perhaps the image of an old fertility goddess. The story connects the worn body of the goddess to the downtrodden mother Merete – in whom a saving love is glimpsed, a source of life. But Merete is raped by the rulers of the city and killed by a mob. It happens “when the populations of those regions had been expecting the last judgement to take place” – but the last judgement is in this tale an ongoing process: the murder of the small image of love.

Love’s indissoluble connection with death is the subject of Sveket. En berättelse (1966; Treason. A Tale). It varies the motif depicted by Selma Lagerlöf in Kejsarn av Portugallien (1914; The Emperor of Portugalia): the hard love between a father and a daughter – for Trotzig it is at once the conflict between what is “sense, word, future” and what is on the other side of the borders of words: “the smile of a madman, a dream, a torn up sweetness.” The father, Tobit, shuns the threatening dissolution that love turns out to be – his helpless love for his daughter and the brutal treason against her are inexorably woven together.

In Selma Lagerlöf’s tale, a world war is hovering as an ominous background. In Sveket the world wars have now become two, and the story treats of an afterwards which does not just relate to the contrite father, but to all people in the century of slaughter.

“How could love turn into destruction?” the text asks. The text responds, not with psychological explanations, but by transgressing thematic and formal limits. Thus lyrical prose expresses how humankind is washed clean “like sand beneath the waves”, while the story also disturbingly lingers on the image of the human being at the border of the disgusting, where she is sacrificed “helpless without a will of her own”. Writing becomes a way to make the sacrificial victim recognisable and known, this stranger marked ineradicably by treason: “the denigrated and ruined face of a child.”

Is not Birgitta Trotzig really a lyricist? The most intense parts of her work take the shape of poetic prose fragments or of lyrical vision. But narrating the “path between birth and death” stands as a necessity. In Sjukdomen (The Disease) from 1972, this narrative is about the abandoned Elje, “born a night in March in 1914, the year when the world in all parts would soon lie in burning warfare”. For a long time the narrative moves in a landscape of motherlessness, which above all is a dissolving language: “Everything turns inwards. It is afflicted with something white. It doesn’t function” – this is Elje’s view of the world, but also that of the story as it moves from the disjointed outer world into the wilderness of the mental hospital.

The lives of Elje and the story have another side: an existence in which the father is everything. The father is the humiliated, unemployed proletarian: “his whole body ached for order as if for a dressing of its wounds.” The life’s work of order becomes the son, who is taught the lessons of the hierarchic world order’s punishing God.

In the depiction of the motherless world and in the portrait of the misguided proletarian is thus anticipated the subsequent depiction of the Fascist war. In yet another dialogue with Lagerlöf’s Emperor-narrative, the son is led into madness. In a maddening parody, Elje must formulate the teachings of the patriarch: “– chop off and rape, the emperor cried, chop off and rape into the least fertile recess! My legions! My legions! My Lords! Cut off and bury, cut off and bury!”

The parody is made real. From the depiction of Elje’s downfall, visions of the World War’s phases grow in a language that reconnects to the genre of apocalypse, the Book of Revelations or the Prophecy of the Völva. The concluding words become a section of grief where the woman-killer Elje in his hour of death hears “the earth crying”. And the narrative can finally depict the collapsing world as a whole: “the doomed birthing world”. The narrative thus follows the trail of the old rites and myths: a movement deeper still into the regions of grief and loss, where finally – purified, released – the result must be the word, an address that takes the shape of a prayer. In Sjukdomen it is: “Have mercy”.

The modern world born out of the Second World War stands like a world of blinding light, a Kafkaesque world where men move about helplessly: “In the flaming dying light the small man grows like an insect. The streets run empty at dawn. He runs with them. They run with him. Like a fly working its way across the insurmountably lit emptiness. If only he could get out of the light. But the dawn flames like a song of triumph over everything and everyone: all gates are locked, all windows barred. He cannot escape.”

Sjukdomen (1972; Illness)

The great narrative Dykungens dotter (1985; The Marsh King’s Daughter), forms a counterpoint to Sjukdomen in that the mother, and with her the pregnant and birthing body, is the centre of the narration. A woman walks through some part of twentieth-century Sweden. She carries a new life within her, and therefore she also carries death and darkness – Birgitta Trotzig depicts the pregnant woman’s life as the life of the double body, that which contains life and death in inclusive pervasive ambivalence. The carnivalesque world view in which life is a spun whole of creation and destruction – which otherwise moves as a sub-current through all Birgitta Trotzig’s other work – dominates here.

Birgitta Trotzig’s woman – called Mojan from the Scanian children’s word for mother – is drawn with a few, elementary strokes. Her strength, her diligence – she comes from the poor parts where life was silent, hard work. Her terror, after the confused abandonment of first love, for everything that can make her slip into the deep, away from the world of those who “belong”. A basic theme becomes Mojan’s and society’s fear of the child and its connection with the quagmire of life and death.

“Thus time passed, thus time stood still”. In the world marked by war and treason this formula gains a shade of revulsion or horror: must it ever continue, humankind’s unending drift towards destruction? But then, next to the historic time and the time of the life-span, the stories create a time of transformation in the lyrical fragments. Here the linear chain of events is broken, here birth and death, ‘paradise’ and ‘wolf-age’, become one and the same. The hungry one is within the border of the other. Damaged life is the start of life – Mojan breastfeeds a little girl who is the new creation: “The world is still small. She sets her sore breast into its mouth and lets it suckle.”

Dykungens dotter ties in with the tradition of Swedish working class literature: the depiction of the Modern Breakthrough seen from the point of view of a worker. As with Moa Martinson, the focus is on the pregnant woman and the mother-daughter. But the point of view is different: a society heading for “the grey-white city of apathy” – “where everything living, the soft flesh, the plants, the animal worlds, everything that is soft in organisation or composition will perish. And what spirit’s electrical radiance will rule? The voices of the wind heard in the great Deep of the World.”

The transformative fragment is presented in a purer form in the prose poem collection Anima (Anima) from 1982. Here Trotzig’s lifelong narrative of ‘deviation’ is summarised in a flash: “How do ice eyes grow forth / the deep cold.” Next to these markings of dissolution, Anima creates images of life as a continued whole. The connection between cosmos and the earthly and human is conjured by an I that “sees into the green”: “in what way I am parted from it, I am not separated from it, I exist in an eye.” Visions, memory fragments, dreams, foreign poems are woven together in this seeing, which does not separate distant from near, butterfly from human, myth from life-experience: “everything is roots, connections, circulation of blood.”

The traits of legend and rite are also found in the shorter narratives. Levande och döda (Living and Dead) from 1964 takes as its theme vulnerable and exposed living as opposed to fortification and petrification, a battle that remains a draw. In I kejsarens tid (1975; In the Emperor’s Time), the fairy-tale connection is purified and concentrated into basic elements: a mother, a father, a daughter, an emperor. There is a kingdom whose centre is the large prison island, “built from ice, black walls, and blood”. A kingdom that will one day be torn apart. And the emperor’s mutilated body will float in the water.

In Anima, lines to other, related poets – Anna Achmatova, Rainer Maria Rilke, Paul Celan, Marina Tsvetajeva, Boris Pasternak – are drawn more explicitly than in Birgitta Trorzig’s narrative works. Fragments of their poems or life-stories enter into and impregnate the world of Birgitta Trotzig, become concentrated into portraits drawn with lightning speed, or transformed into elements of a new cosmogony.

This dialogue with related authors forms the core of Birgitta Trotzig’s essays, an important part of her oeuvre. The essay collection Porträtt (1993; Portrait) has the subtitle “Out of the History of Time”. It is about seeing the writings within their time, not as imprints of it but as passageways into its deep reality. As she writes in the essay about Anna Achmatova: “some works are like secret gateways directly into the real life of their time.”

Something similar can be said about Birgitta Trotzig’s own works. In a time of confusion, someone laid an ear to the ground and heard it cry. An eye saw the treason, the killing, as well as the continued creation. An authority of dialogue and invention has emerged, in which the language of the old patriarchal traditions has loosened into a life-giving downward movement. Just as present-day language is impregnated with the sounds of legend, martyrdom, sagas, and songs of praise – what wealth.

In “Ormflickan” (“The Worm Girl”) from I kejsarens tid, something is depicted that may be the Creating Woman in Birgitta Trotzig’s world – a creature of transformation, with roots in the prehistoric healing women. Her separation from the old world leads her into the borderland between nature and culture, between self and world, where she learns that all the languages of existence really are one in the end: “The language of the pebble is one, that of the firestar and the death planet is another – darkly hovering – that of the swarming butterfly is a third, that of humanity a fourth, and yet it is all one clamouring language.”

Translated by Marthe Seiden