It is traditional for Eskimo women to be able to express themselves on equal terms with men. According to the Danish polar explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, all men and women, and sometimes also children, had their own poetry. Admittedly, the sexes in Eskimo society lived in their own separate worlds, busy with their own carefully defined tasks, but they came together in poetry. Songs were considered to come to people from the outside, from the powers that controlled the world, just as stories were inherited from forefathers and represented the complete wisdom of the human race. No one had a patent on this truth. Thus, even the most humble old woman, who lived her life on the fringes of society, could step right into the centre of the community the moment she picked up the drum and began her song.

In both Greenland, Kalaallit Nunaat, and the Sami Language Area, Sápmi, writing was introduced during the days of colonisation. The first hymn written by a Greenlander was printed in 1858, the first novel in 1914, and since then Greenlandic literature has developed with a number of life-long, well-established authorships. The first work of fiction in Sami was a novel written in 1912, and three years later the first book of poetry and short stories came out. This was followed by sporadic publications in the 1930s and 1940s, until Sami literature truly came of age in the 1960s and 1970s.

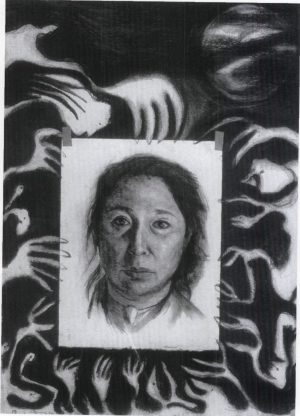

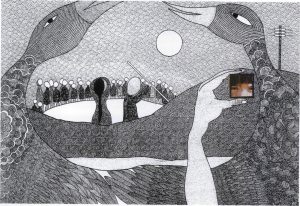

Høegh, Aka (born 1947): Selv-portrait, 1992.

For this same reason, women could also become shamans (angakkok, in plural angakkut), and there were no restrictions on what women could or should experience in their dealings with the other world that did not also apply to men. Young women appear to have been trained on equal terms with men – but there were far fewer women who completed training and became active angakkut for the simple reason that the woman’s training would come to a sudden end when she gave birth to her first child. The training as angakkok took place out in the wilderness far from people – and what woman could abandon her baby for days and weeks on end to sit by a lakeside, stroking rocks and expecting to be eaten by a giant bear from the bottom of the lake? For this same reason, there also appear to be signs of quite a number of voluntary abortions in the female shaman biographies that we are in possession of. At that time, too, a woman could desire formal training so strongly that other considerations had to give way or at least be postponed.

Thus, it was not until the introduction of new cultural and social institutions based on Danish traditions that men had a monopoly on the safeguarding of ideology and spiritual life. It was the followers of the Danish philosopher and educationalist Grundtvig who had the greatest influence on the development of the educational system in modern Greenland, and the national-romantic ideals in Grundtvigianism, the concepts of myth, living work, and mother tongue as the foundation for the people’s soul, have had a significant influence on the establishment of a strong national identity in Greenland. The Inuit role distribution, with the woman in control indoors while the man was out hunting, fit only too well into the ideal Grundtvigian home where the woman worked in “the quiet circle” and participated only indirectly, as a child rearer, in society’s ideological and political development.

The educational system was thus based on the men; men and men only were given an education beyond basic schooling, and when it was decided in the 1930s to create continuing schools for girls, it was still for the express purpose of making sure that the Greenlandic men could find women of an appropriate spiritual level among their own kind – women they could consider worthy of becoming mothers to their future children. It was not until after World War II, when Greenland was opened to the outside world and great efforts were directed at turning Greenland into a modern industrialised nation, that investments were made in women’s education and preparation for independent business activities.

Important dates for Greenland: colonisation began with the arrival of Hans Egede in 1721 and ended with the constitutional amendment in 1953 in which Greenland became a part of the Danish Kingdom. Greenland and Denmark still maintain relations in what is called the Commonwealth of the Realm, but in 1979 Greenlandic Home Rule, which gave Greenland powers of self-government in all internal affairs, entered into force.

The Sami People – Assimilation and Opposition

In the early sealing community, the Sami were nomads who exploited the available resources in a continuous annual cycle. In the 1600s, a differentiation took place, such that most of the Sami settled, either as fishermen along the coast and in the fjords, or as farmers. However, berry picking, fishing in inland lakes and rivers, and so on continued, and the Sami were never fully dependent for their survival on only one resource. The nomad existence was only continued by those who tamed the wilderness and made a living as reindeer herders.

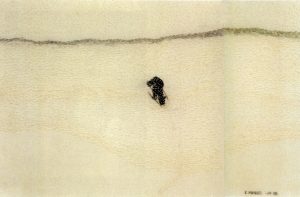

Marakatt-Labba, Britta (born 1951): Han for. Embroidery. Year unknown. Private collection

The Sami’s song is called joik and it is assumed that it has been an important aspect of social life, both by singing myths and stories in epic poem form and by singing a personal joik: it was not until someone had their own song that they were considered independent members of society. This tradition has died out with the exception of a few limited areas, but the joik exists to this day, taking on new forms and serving as a vital part of Sami life. The personal songs can describe a person in a few words and with expressive use of rhythm and melody, and can easily be compared to modern lyricism. The joik also represents one of the main sources of inspiration for modern Sami songs and poetry.

Both men and women were permitted to sing, although it was usually the men who became shamans(Noaidi). The joik were also important for shamans who could, with their help and with the help of the holy drum, enter a trance and journey to the spirit world. This link to the ancient Sami religion was one of the main reasons why the missionaries ardently sought to eradicate and forbid the joik. One approach was to introduce the death sentence for practicing shamanism. The holy drums were gathered together and burnt as instruments of the Devil.

The Literary Wave after the 1970s

Women’s modern literary production began with the political trends in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Greenland and northern Scandinavia were discovered as regions, and the Greenlandic and Sami peoples began to view themselves as ethnic minorities: no longer must they feel inferior to the dominating cultures, now the people’s own voice should be heard in its own language. A new generation of writers emerged in protest against the cultural invasion of the Danes, the Norwegians, and so on, and the women also got involved. This was the same period as the decade of the women’s movement.

There were many opportunities for publication. Many writers had their first texts printed in newspapers, and the radio in Greenland served as an excellent “intermediary” between oral and written forms.

In the 1800s, literature was primarily disseminated through the circulation of handwritten texts. Karoline Rosing (1842-1901) was the daughter of a sealer, but was also the granddaughter of the local priest and therefore learned Danish. She translated a number of texts, primarily suspense stories, into Greenlandic, as well as translating for the Greenlandic newspaper Atuagagdliutit, but has never earned a mention in the annals of literature.

In Greenland, the many anthologies promoted women’s entrance on the literary scene. However, in the two anthologies that became a kind of initiator of the literary wave of the 70s, Puilasoq pikialaartoq (1970; The Bubbling Source) and Allagarsiat (1971; Letters I have Received), women were only represented by a single text in the latter publication – and the editorial board even found it necessary to emphasise that the Bolethe in question was not just anybody, but the wife of the late Jonathan Petersen, Greenland’s great hymn writer. However, in the anthology Suluit (Wings), published sporadically from 1978 by the Greenland writer’s association, women are represented in increasing numbers, as is also the case in the two bilingual Danish/Greenlandic anthologies published on Danish initiative: Inuit, ny grønlandsk lyrik (1980; Inuit, New Greenlandic Poetry) and Inuit nipaat, grønlandske digte i 1980’erne (1989; Inuit Nipaat, Greenlandic Poems in the 1980s).

Two songs and one melody by Bolethe Petersen (1892-1986) are included in the new Greenlandic songbook. The extent of her output, and of her influence on the work of her husband, hymn-writer Jonathan Petersen, is not known with certainty.

In Norway, a special “committee for the promotion of Sami literature” was appointed in 1973. Two years later, this committee was incorporated as a subcommittee to the Arts Council Norway, and since 1973 has published its own series called Cállagat (Writings). Many authors have made their debuts here.

In 1984, the Nordic Council of Ministers recognised Greenland and the Sami Language Areas as members of the Nordic region, also in terms of literature. As a result, Greenland and Sápmi can now each nominate one candidate per year for the Nordic Council Literature Prize. Up to the mid-1990s, two Sami women authors and one Greenlandic woman author had been nominated for the prize.

Greenlandic Novels

The first Greenlandic novel written by a woman was published in 1981: Búsime nâpíneq (Meeting on the Bus). It was written by Mâliâraq Vebæk (born 1917), and was translated into Danish the following year by the author herself, with a somewhat different title: Historien om Katrine (The Story of Katrine).

Historien om Katrine was written not only for a Greenlandic audience, but to a great extent also for a Danish audience. The novel takes place during the period when many Danish tradesmen came to Greenland, and like many other Greenlandic girls, Katrine believes that all Danes are rich and that happiness is to get married down in Denmark. Upon her arrival in Copenhagen, however, she discovers an entirely different reality. Her Erik had fled to Greenland because he had a great deal of problems at home, and nothing between them is the way it was up in Greenland. They have children, but their relationship falls apart, as does Katrine. Lonely and unhappy, she takes up with other people from Greenland and learns to look for the bright side at the bottom of a bottle. After their divorce, her husband is awarded custody of their daughter, while Katrine gets lost in the Danish legal system with all its “offices” and, unable to find meaning in her life, she jumps into the harbour.

Åndemagersken Teemiartissaq. Photo. Photographer: William Thalbitzer, 1906. Dansk Polar Center

The Greenlandic title, Meeting on the Bus, refers to a less obvious narrative in the book: the relationship between Louise and Katrine. Louise is Greenlandic, too, but her story is the positive counterpart to Katrine’s. She gets everything she ever dreamed of: a terraced house, a kind husband, wonderful children, even a part-time job. But she has also paid the price, and that is what Katrine makes her embarrassingly aware of. Louise comes into contact with Katrine because she suddenly longs to speak Greenlandic, and the reader clearly senses how Louise becomes involved in the story of the life Katrine lives with other people from her home country: Greenlandic food, games and songs, Greenlandic jokes. But these things are all forbidden, unaccepted by the Danes. The Greenlandic life is viewed by the Danes as foul-smelling, noisy, and disorderly.

Her meeting with Katrine reveals to Louise that her own world view, in which everything is perfect and just, is based on an effective repression of large parts of her own nature. For Louise, Katrine’s death is an awakening and a realisation. At the funeral, Louise listens properly for the first time to what the rebellious young generation is saying about the introduction of Home Rule.

While Mâliâraq Vebæk views things somewhat from the outside – with Denmark as history’s theatre – Greenland’s development is depicted in truth from the inside by Dorthe Nathanielsen (born 1934) in the novel Aani from 1986, which follows the life of the main character Aani – an ordinary Greenlandic woman, the kind “nobody expects to have anything to say” – from her childhood in a small settlement sometime in the 1930s.

For little Aani, the world is not the same as it was for the older generation. Her mother works and works, and naturally she involves Aani in the work she will one day take over, but Aani is not interested. Once in a while the family receives a newspaper, Atuagagdliutit, and Aani prefers to lose herself in the photos and text from the big outside world rather than fetch water and repair kamiks. Aani demands time for herself.

Aani loves Jens, whom she has grown up with, yet she breaks up with him. She knows that with Jens she will have a life like her mother’s and Aani wants something different, which she may be able to achieve through the Danish men who have begun to show up in the settlement during the summer. So Aani travels to the city, gets a low-paying job, begins to hang out with the Danish workers in the barracks, and is on her way to becoming a woman for whom “things go badly”. Instead of sinking to the bottom, however, Aani goes home to the settlement, has a baby, and slowly rebuilds her life.

She marries Jens and together they have six more children, so Aani ends up living a life similar to her mother’s after all.

Aani’s daughter gets as far as Denmark, on a study stay, and when she becomes pregnant, she insists on having an abortion and completing her studies. Aani realises that her children must live their own lives. She herself, despite her attempted rebellion, has her roots in the Greenlandic village. When she stands at her mother’s deathbed, her self becomes whole and she feels as though it was not until that moment that she became an adult and was ready to take over her mother’s role as the person who carries on the tradition, despite all that has changed.

Historien om Katrine has been translated into several languages, including Sami in 1988. Mâliâraq Vebæk wrote another novel, with Katrine’s daughter as the main character, Ukiut trettenit qaangiummata (1992; Thirteen Years Later). She has also published a book on the history of Greenlandic women: Navaranaaq og andre (1990; Navaranaaq and Others).

Dorthe Nathanielsen has continued writing within the narrative tradition and has retold/reproduced a number of stories about the famous great hunter Ujuaansi, which her aunt told her as a child. The stories were originally written for the radio but have since been published in Ujuânse Avalak (1982). Thale Eriksen (born 1919) and Grethe Guldager Thygesen (born 1937) have both published novels. Thale Eriksen’s novels are strongly religious, while Grethe Guldager Thygesen seeks to create a female main character who can carry on the ideals from early Greenlandic literature, in which the fictitious characters appeared as role models for their countrymen. Her works also take as their point of departure love and marriage between a Greenlandic woman and a Danish man.

Dorthe Nathanielsen’s aunt was the famous and treasured storyteller Bibiane Mikkelsen (1882-1964). Some of her stories have been preserved on tape recordings in Greenland’s national radio archives. Bibiane Mikkelsen lived for a period with the previously mentioned hymn writer, Jonathan Petersen, but public opinion in Nuuk was very much against the liaison, and they ultimately parted ways.

Sami Poetry

The first book in Sami written by a woman was Kirsti Paltto’s (born 1947) collection of short stories Soagnu (Suitor Dealings) from 1971. But poetry appears to be the genre that Sami women have had most success with. It starts with Inger Utsi (1914-1984), who is indicated as a co-author of her husband’s, Paulus Utsis’s, final collection of poems, published posthumously. A recurring image in Inger and Paulus Utsis’s poems is the firepit, the fire as the symbol of Sami culture, the light and life-giving force that brings the Sami together as a people. The fire must be constantly fed with new fuel, and it is vital that the embers are kept alive. “Dark night / invisible horizon / The fire’s glow sparkles / on the snow a way off / Darkness pushes the two / closer to the fire / The man tends the fire / frightens the darkness”.

An exception to the rule that Sami women writers are poets is Kirsti Paltto, who has the greatest and most comprehensive production of all Sami writers. She has written children’s books, poetry and short story collections, and radio drama, as well as a series of novels, including: Guhtoset dearvan min bohccot (1987; May Our Reindeer Graze in Peace) and Gurzo luottat (1991; Sinister Paths). The short story collection Soagnu is based on ancient stories, while later short stories deal more with modern women characters, as in the collection Guovtteoaivvat nisu (1989: Two-headed Woman).

This line can also be found in the work of Kirsti Paltto in a more directly political version. Her poem about a Sami future becomes more problem-oriented: “I come from a time / that crushed and ground / broke into pieces / led many away / […] suffocated the glow / which was supposed to warm me”.

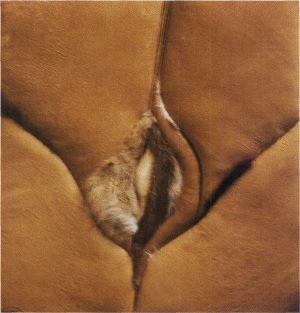

Huuva, Rose Maria: The Flower of Tenderness, 1984. Reindeer hide. Samiske samlinger. Karasjokk, Norway

Both Kirsti Paltto’s and Rauni Magga Lukkari’s (born 1943) poems are full of love, but also of a nagging fear of the future, as expressed by Kirsti Paltto thus: “[…] but some day you will take onto your own shoulders / my people’s heritage, which I leave to you / my son”, while Rauni Magga Lukkari writes: “How can I lead you / when I am so lost myself”. This is a clear expression of the feelings many Sami women have of bearing the primary responsibility for their children’s chances of retaining a Sami identity in a rootless world.

Rauni Magga Lukkari’s poetry collections also deal with the possibility of retaining a Sami identity. There is a sense in her poetry of a clear development throughout her works. Thus in the first, Jienat vulget (1980; The Ice Recedes), several themes are taken up to which she returns in her subsequent works. Rauni Magga Lukkari’s second book Baze dearvan Biehtár (1981; Farewell Biehtár), in which the novel in poetry-form becomes even more distinct, has one coherent narrative throughout the book, about Biehtár who leaves the poetic speaker for another woman. This new woman in Biehtár’s life represents another culture, other values. The book tells about the pain caused by Biehtár becoming someone else by living in a majority society. It also paints a distinct portrait of the problems that can develop when two people of different cultural backgrounds embark on a life together, even if the distances are no greater than between the Sami and the Norwegian/Swedish/Finnish cultures.

The third of Rauni Magga Lukkari’s books, Losses beaivegirji (1986, published in Norwegian under the title Mørk dagbok; Dark Diary), which was nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 1987, is in many ways a kind of summary of the themes of the previous books. We meet a woman who appears to have overcome the loss of Biehtár, a woman who is in the process of finding her own identity. This is expressed by depicting the strength and solidarity among women. We hear her strong plea to the young not to let history repeat itself. And we meet a woman who embraces the pleasures and the love that life can bring, but who is not dependent on a man to share life with – an attitude that becomes even clearer in her fourth poetry collection, Mu gonagasa gollebiktasat (My King’s Golden Clothes), published bilingually in Sami and Norwegian in 1991. When read consecutively, the four poetry collections demonstrate how Rauni Magga Lukkari has gradually moved away from the clear focus on ethnic emancipation to a more self-oriented focus. The female poetic speaker’s choice is based not so much on her cultural and ethnic background as on her own desires and longings.

Even though the political conditions are expressed differently by Kirsti Paltto and Rauni Magga Lukkari, they still clearly speak about the same cause. Kirsti Paltto places the majority of the emphasis not on the sexes but on being a minority without power and decisive (economic) influence. Her poetry also thematises the fear of war, which all nations must share, and she uses symbols taken from, among others, the ideologies of the American Indians. Thus, the poetry collection Beaiv-váza bajásdánsun (1985; Dance Until Sunrise) uses the eagle as a symbol of solidarity with other indigenous peoples in the Fourth World. Rauni Magga Lukkari, however, is more concerned with themes from women’s lives and the family sphere.

The last two poems in Losses beaivegirji can, when read separately, be viewed pessimistically with regard to a Sami future. The next-to-last poem reads: “I have gone so far away / that I can almost find my destination / The foreign known / practically brother / mother’s hand warmer / awash in foreign words / Paths open up / with the flame / towards unknown seas”. This poem suggests that the Sami are disappearing into society at large; however, the flora of Sami place names in the final poem again brings one back to the landscape of childhood. When read consecutively with the final two lines, “And life so distant / from Luosnjársuolu”, it is understood as a confirmation of the fact that the Sami no longer have an everyday life in the mountains around them and can therefore feel cut off from their origins. And yet their identity remains clear – you are Sami just as the literature you write is Sami.

Modern Sami culture is characterised by its multicultural expression. Poets are also musicians, joik singers, or artists, or perhaps all three. Mari Boine is the most internationally known Sami artist today. Her world music/ethno-sound with references to, among other things, the Sami joik has triumphed throughout the world. She writes nearly all her own lyrics, but it is primarily the intensity and communicative strength of her musical expression that has had such an impact. Among her works, Gula gula, Goaskinviellja, and Leahkastin are particularly noteworthy.

Tradition and Renewal

The relationship to tradition has been key to maintaining the ethnic identity of both Greenlandic and Sami women. This theme is more explicitly expressed by Kirsti Paltto in the short story “Seidestenen” (The Seid Stone) from the collection Soagnu, which was printed in Norwegian translation in the anthology Ildstedene synger – samisk samtidslitteratur (1984; The Fireside Sings – Contemporary Sami Literature). One night when nothing is as modern and reasonable as it usually is, the first-person narrator visits Old Mother Elle, who brings her to the seid stone, the old Sami sacrificial altar. Only when the narrator has established ties with the past, which she knows can never be broken, can the old lady die, leaving the narrator to the future – both happy and frightened about what has happened to her.

Just as the old people played an important role before the advent of written language as the collective memory, so the oldest generation today represents the last ties to the past. And the past is an unavoidable topic in the question of ethnic identity, because the life lived by a people’s forebearers forms the background they wish to retain as their distinguishing feature in relation to the invading Nordic cultures.

Is the Sami people’s existence as bearers of a unique culture associated with a life in pact with nature? Can you continue to be Sami even when you live in a city and no longer have anything to do with reindeer? ‘No’ seems to be the answer of the Sami author who writes in Norwegian, Annok Sarri Nordrå (born 1931) in her trilogy about the Sami woman Ravna, Ravnas vinter (1973; Ravna’s Winter), Fjellvuggen (1975; Mountain Cradle), and Avskjed med Saivo (1981; Farewell to Saivo). Assimilation is presented as the only alternative for the Sami, who no longer live the “life of the mountain people”. These stories, which are set in Sweden, depict the reindeer herding culture as it was before the 1960s as the true Sami lifestyle.

The question of who is truly Sami is also the point of departure for the first novel written in Sami by a woman: the novel for young adults Kátjá (1986). The author, Ellen Marie Vars (born 1957), took up one of the bitterest periods of the Sami collective memory: the stay at the boarding school where the Sami language was strictly forbidden and where they were taught to look down on anything Sami. On top of everything else, the main character was bullied by the reindeer Sami because her parents were settlers and did not keep reindeer. The book triggered a heated debate when it came out in 1989 in Norwegian, and in 1993 in Greenlandic.

Like Annok Sarri Nordrå, Aagot Vinterbo-Hohr (born 1936) writes in Norwegian. She spoke Sami as long as her grandfather lived, but is unable to write Sami. With the title of her debut work, Palimpsest from 1987, she clearly signals the aim of her literary project.

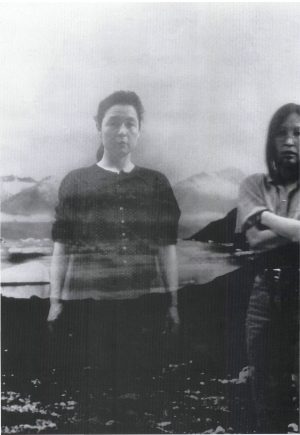

Rosing, Ina (born 1965): Thule nat, 1993.

Palimpsest is an intellectual and reflective book, at once international and yet clearly Sami. The author says: “I read the possibility of a truer story and write.” And the story she tells is viewed from the point of view of an ethnic minority woman. In it, Sami culture goes hand in hand with theoretical knowledge, and together the two approaches conceptualise a number of control mechanisms and power relations in society that are oppressive in terms of both gender and ethnicity: it is a story that has parallels in many other places throughout the world. The author sometimes uses words and expressions that are influenced by Sami, which gives Sami readers of the book a good sense of the Sami language underlying the text. Towards the end, the Norwegian surface is broken to make way for quotes from Rauni Magga Lukkari’s poems in the original Sami language. The elucidation of the palimpsest has, in other words, produced a new Sami text.

Palimpsest comes from Greek and is a piece of parchment from a scroll or book, from which the text has been removed to make way for a new text. Palimpsests are used as a source for lost texts from distant times, since the erased writing can be made visible again with the use of chemicals or ultraviolet light.

But in addition it has perhaps also brought a long-hidden Sami-ness out into the light. In many of the Sami Language Areas that have been longest under Norwegian influence, people have mistakenly thought that the de-Samification process was complete.

The Return of Humour

Identity, ethnicity, and tradition have been central aspects of the debate in Greenland as well; however, it has been the women who have managed to have the freest relationship with the adopted ‘tradition’. The tradition is not necessarily liberating on all counts.

The Greenlandic literature written by men presents the image of the hard-working woman, bordering on the self-denying, self-sacrificing woman standardised in an encomiastic framework borrowed from the nineteenth century Denmark. We have seen this image, if not rejected then at least thematised and problematised, in the work of Dorthe Nathanielsen.

However, it is interesting that it would turn out to be a woman who reawakens the humour and pleasure at the grotesque and the burlesque in writing, as is the case in Mariane Petersen’s (born 1937) poetry collection Niviugaq aalakoortoq allallu (1988; The Intoxicated Fly and Other Poems). The book was the first poetry collection published in Greenlandic by a woman and was nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 1993.

A humorous-grotesque tradition closely related to the carnivalesque was central to the oral culture, but was practically purged when the stories were written down and passed on in print form to coming generations. At the same time, all bodily and sexual references were toned down.

Arke, Pia (born 1958): Selvportræt med kusine. Year unknown. Private collection

The first modern fiction was developed in close association with the religious revival, which sought to bring progress and enlightenment to the Greenlandic fold – a movement based on the philosophies of Grundtvig, but also having strongly Pietistic elements. In this way, a very fixed framework was established for literature as an edifying and educating medium, and even though the motifs and content have changed, the framework has remained the same. It is as though the ceremonial dress is donned when entering the literary sphere, thereby excluding literature in a way from daily life, in which humour continues to be the preferred mode of expression. A good evening in Greenlandic company is not an evening full of talk and discussion, but an evening full of laughter. Mariane Petersen, with her little humorously described situations, brings writing back to the everyday world and the everyday language, and this has undoubtedly contributed significantly to the popularity of the collection, even in the smallest settlements. The tone is set in the very first poem, which gave its name to the collection. Gleefully, the poetic speaker observes a giant blue bottle fly that has imbibed the beer leftovers on the table and is now reeling through the air. “I hope you really enjoy your hangover!” she says, thinking about all the flies that have laid eggs in the freshly cleaned cod and spoilt it completely. A beginning like that encourages you to read on, even though the poems become gradually more serious.

Mariane Petersen subjects some of the most inviolable symbols in the representation of Greenlandic tradition to a kind of humour and comedy that automatically brings them down to a quite different, informal stylistic level. For example, the much-lauded hunt is not only depicted in its heroism, but also considered in its comic aspect when the otherwise infallible hunting skills do fail. Even nature steps down from its mythological pedestal of Arctic grandeur to become rather commonplace surroundings.

Whereas the Greenlandic novel had primarily dealt with the meeting of cultures expressed through marriage between a Greenlandic woman and a Danish man, the problem of identity is as good as absent in Mariane Petersen’s first poetry collection. Even though the majority of the poems are set in and around Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, life is unmistakably Greenlandic and no different from what characterises life in most other parts of Greenland: people have jobs within one of the new social institutions and are occupied with hunting and fishing in their spare time. Up through the 1970s and 80s, there has otherwise been a general literary consensus to condemn the city and city life as alienating and “unGreenlandic”, but in the work of Mariane Petersen it becomes clear that in Greenland, nature is never further away than it can always be seen from the living room windows – even in Nuuk.

In this same way, the airplane flight between Greenland and Denmark, so fraught with symbolism, has found its release. For Mariane Petersen it is no longer a one-way ticket but a continuous flight back and forth between the two destinations. Below the poetic speaker lies Denmark: “[…] that tiny little country / flat and without mountains / as though pressed with an iron”. Not much in comparison to the Greenland that appears three hours later: “An immense country / with high mountains / snow-capped / the ocean full of ice”. One can hardly blame the speaker for concluding:“It sure is good that such a country is one’s homeland!” Things have been put into perspective in relation to the image of the colonial power as the all-embracing “Mother Denmark” that Greenlandic literature spent decades breaking away from. However, the description of the tiny flat country also contains a love and tenderness that testifies to a growing sense of reconciliation. A reconciliation that not only applies to the relationship between the two countries and the two populations, but first and foremost between the two sides of the Greenlandic consciousness. The meeting of cultures has been internalised long ago, becoming part of the culture itself, for better or for worse.

The Latest Trends

In Greenland it has almost entirely been older women who have manifested themselves in the literary community since women joined the literary ranks back in the 1970s. The energies of the younger women were apparently consumed by politics and administration – a trend that has also applied to Greenlandic literature in general. A number of the poets who had just had their literary breakthrough or were on the verge of it instead became top politicians in the new Home Rule government. For the women, this has resulted, in addition to the late start, in the ‘loss’ of an entire generation of writers. There is a significant gap of twenty-two years between Mariane Petersen and the woman writer from the younger generation who has had the greatest impact: Jessie Kleemann (born 1959). Jessie Kleemann has published poems in a number of anthologies and has represented Greenland at many events abroad, including the Nordic Poetry Festival in New York, where her poems are also represented in the festival’s anthology The Nordic Poetry Festival Anthology (Sweden, 1993).

Jessie Kleemann belongs to the generation that journeyed not only to Denmark, but to the rest of the world as well. Thus, the experience of belonging to an indigenous people has been lived in reality, achieved through extended stays with the Sami and the Inuit and Indians in Canada, while visits to the major cities of Europe and America have brought contact with the latest trends. All this is amalgamated in Jessie Kleemann’s art. An entirely new language develops in the meeting between the most “indigenous” and the most “modern”, loaded with meanings from an ancient Shamanist form of experience inscribed in a modern consciousness. Stylistically, Jessie Kleemann thus makes a break from the narrative prose poem as the dominant form of poetry in written Greenlandic literature. Instead, she tries a more expressionistic, often surrealistic style in which the plot is played out on an inner plane, with the past as a metaphor for a modern exploration of mental life. Jessie Kleemann was originally a painter and graphic artist, and the sense for creating visual images is clearly felt in her poetry, which in form also draws on the use of metaphor and the hidden, alluding form that characterises the drum song.

Høegh, Arnánnguaq (born 1956): Untitled, 1976. Drawing. Private collection

Two birds

three

are about to devour a man

they eat him

they fill themselves with his heart

Pool of blood –

Where is your lover?

Here are the birds

they’re still eating

In the work of Jessie Kleemann, eroticism returns to poetry in its many multi-faceted aspects, with all the aggression, passion, and violence that comes with it – especially under these skies where nature herself paints everything in contrasts, from the dark of the Polar night to the light of the midnight sun. The Inuit viewed the safe, warm house as a metaphor for the female body; in the work of Jessie Kleemann, the body of the poetic speaker is a house, but a house can also go up in flames – and Jessie Kleemann’s house is in full blaze. Passion is apparently the only possible contact between people. Between the house and the surrounding universe there are no permanent walls: the mighty ocean washes in while the air turns red like a beating heart, breathing in and blowing its air back onto the speaker, who can expect the moon to listen and the stars to watch as she screams from the depths of her mind. But between people there are very fixed boundaries: the day of the communal dwelling has long passed. “Uanga Taanna Uanga” – I is me not you, “My name is Uangaannalik / Only I.” Thus this longing for the transgression which – even for the most vampire-like connection – only for a rare, select moment can resemble true union. When this finally happens there are no words, because “the words have no desire to be said” – the words come only afterwards, and so Jessie Kleemann’s words generally denote separation and longing. And yet, the keyword for her poetry is above all vitality. In Danish the words for heart and pain rhyme, while in Greenlandic, heart and life stem from the same root word.

“The Sami Project”

In the Sami Language Area, or Sápmi, the cultural aspects of the struggle have always been the most important for “the Sami project”, and the number of women writers increased steadily throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Ellen Sylvia Blind (born 1925) focuses on the religious in her two poetry collections, while Marit Hivand (born 1936) builds on the narrative style of the epic joik poetry in her book Eallin bálggis (Life’s Path) from 1987. After three children’s books, Inghilda Tapio (born 1946) published her first poetry collection in 1995, Ii fal dan dihte (Not Exactly Why). The collection comprises remembrance poems as well as little observations of how different Sami life is today compared to during her childhood. Marry A. Somby (born 1953) had her debut as an author as early as 1976 with the first children’s book in Sami, Ammul ja alit oarbmælli (Ammul and the Blue Cousin). In 1994 she published her first poetry collection, a bilingual version in Sami and Norwegian, Mu Apache ráhkesvuohta/Krigeren elskeren og klovnen (The Warrior, the Lover, and the Clown).

Women have dominated the Sami children’s book genre. In addition to such recognised names as Marry A. Somby, Ellen Marie Vars, and Kirsti Paltto, authors such as Inger Haldis Halvari (born 1952), Rauna Paadar-Leivo (born 1942), Kerttu Vuolab (born 1951), and Inger Margrethe Olsen (born 1956) are also worth mentioning. Kerttu Vuolab has published novels for young adults as well, and Inger Margrethe Olsen has written plays for the Sami Beaivvás theater in Kautokeino.

A new young voice has been brought to Sami literature by Inger-Mari Aikio (born 1961) with her three works Gollebiekkat almmi dievva (1988; Sky Full of Gold Winds), Jiehki vuolde ruonas gidda (1994; Under the Glacier Green Spring), and Silkeguobbara lákca (1995; The Cream of the Silk Sponge). The first poetry collection is experimental in style, cutting the close ties between poet, text, and context, represented by, for example, the joik poetry. Her debut work is innovative in form in a Sami context, following a more international trend than Sami tradition, while the traditional mode of expression is again taken up in her subsequent book. However, it is unvaryingly the female subject that is the focal point of Inger-Mari Aikio’s texts, often with an ironic distance to both herself and the text.

Like the Greenlandic author Jessie Kleemann, Synnøve Persen (born 1950) was originally known as an artist, but since her literary debut in 1981 with alit lottit girdilit (1983; Blue Birds Fly), she has also made a name for herself as a poet. Her debut work is dominated by a blue tone that runs through the text in both the written imagery and the illustrations, emphasising the melancholy content of the poems. In her second collection of poems, biekkakeahtes bálggis (Windless Path), both versions published in 1992, Synnøve Persen refines the short and striking joik poetry to an almost minimalist style in which everything extraneous is cut away and the poems display the stripped nature of their words: “naked trees / seeking / the birds” and “quiet room / leaves fall ”. The book was nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 1993.

In ábiid eadni (1994; The Mother of the Sea), the dark, melancholy imagery is communicated through the consistent black glossy colour of the book, with the two bright red pages in the middle as a contrast. Through all three poetry collections, the author insists on her right to express herself in a boundary-transcending freedom, in which the subjectivist project must not be subordinate to any ethnic or cultural category. She will not be forced into a category. Art is free, and people are free to form their life’s project just as they choose.

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd