In 1962 the educator Martha Christensen (1926-1995) made her debut with the novel Vær god mod Remond (Be Good to Remond). It is the story of Remond, a mentally retarded boy who grows up with his mother and ends up in an institution when his mother remarries and gives birth to a normal child whom Remond attempts to strangle out of jealousy. The story was written with a critical involvement in how society treats the weak; a social realism that Martha Christensen built on throughout her long and popular writing career. In her stories, the social system itself becomes a powerful character that prevails over individual will. When the well-intentioned social machine begins to turn, the system launches a fateful process that contradicts the declared intention.

Martha Christensen’s critical socio-psychology is not directly political in the same way as Dea Trier Mørch’s (1941-2001) stories about the relationship between the individual and society. In her work, the system becomes the necessary organisation and the holistic entity that forms cohesion in individuals’ lives and takes care of them, just as the hospital cares for the weak children and their anxious mothers in Vinterbørn (1976; Eng. Tr. Winter’s Child). However, her attitudes and her entire body of work are a critical depiction of the modern welfare society and its view of humanity. And her texts remain within the social structure she criticises, whereas the critic of modernism Anne Marie Løn (born 1947), following her urban novel Veras vrede (1982; Vera’s Anger), journeys through time, the country, and other types of social life in her search for a positive counterpart to the destructive city. The story of Remond already displays the features that became characteristic of Martha Christensen’s stories. Remond is the weak, helpless, and vulnerable boy who has no understanding of how to behave in any kind of situation. His abilities consist primarily of giving and awakening love. His need is care; his tragedy is the failures he suffers every time his world falls apart. The title of the book is also the narrator’s appeal that we consider both Remond and ‘Remond’, the weak everywhere. Remond’s world is full of characters who became typical in Martha Christensen’s work: the strong educator who chooses the carefree life rather than responsibility, and the well-intentioned superintendant who represents weakness as sensitivity, understanding, and an inability to take what life brings, to be superficial – and free of responsibility.

Through these characters, Martha Christensen addresses her main theme: the fate of weakness, powerlessness, sensitivity, and endless goodness in a society and a system that favours the special type of strength that consists in being able to set, understand, and juggle the social rules and norms. The main characters in her stories do not possess that ability. Either they are, like Remond or Mrs Larsen and her retarded son Jimmi in En fridag til fru Larsen (1977; A Day Off for Mrs Larsen), too dim-witted to learn the way things work – symbolically, Mrs Larsen has difficulty figuring out train schedules and bus routes – or they are too sensitive, full of foolish kindness, which gets them involved in problems others manage to keep out of.

Martha Christensen not only writes about non-heroes, anti-heroes, and their fates, she writes with them in a manner that does not leave the reader in peace. She forces us to identify with her characters, whose lives no one would want to live, and with situations that drag the sober reader down into the maelstrom of disaster. We are placed in a world where good sense does not exist, where the social worker Daniel in Manden som ville ingen ondt … (1989; The Man Who Wouldn’t Hurt a Fly …), out of the goodness of his heart – and out of weakness – neglects to report an assault, which only accelerates matters, making them much worse. A prison sentence leads to brutalisation, according to Daniel. However, his kindness only leads the assailant to kill Daniel’s dog and, later, to be murdered by other young offenders.

The theology student Andreas in Rebekkas roser (1986; Rebekka’s Roses) is yet another of Martha Christensen’s paradoxical heroes, who possesses the ability to listen to and comprehend other people’s problems, but is also considered weak by his father, who wanted a son to take over the family farm, by the girl with whom he falls in love and who uses him in a game with her real boyfriend, and by the village that does not tolerate people who deviate from the norm.

One of her early novels, I den skarpe middagssol (1972; In the Sharp Sun of Midday), holds the key to the logic in Martha Christensen’s technique. It is a first-person narrative about a detective inspector looking for a wife-killer. The narrator is the “son of the chief” and seemingly entirely different from the murderer, the weak loser. However, as the story progresses he reveals a similarity, a weakness, and a wretchedness which in the final lines make the two practically indistinguishable. As in a mirror, he has become wretched by abandoning the ideals of youth, and by “murdering” his wife, whom he calls “the grey”, and whose death by cancer he almost looks forward to. Suddenly, there is not much that separates loser from winner, one weak person from the other, and the moral is that the greater the distance placed between ourselves and the other, the powerless, the neighbour – the weaker we fundamentally become as human beings.

Martha Christensen’s novels have a huge readership, as evidenced by the countless reprints and paperback versions of her works, and especially the film adaptation of Dansen med Regitze, (1987; Dancing with Regitze; Eng. tr. Memories of a Marriage), a novel about an elderly couple in which the husband, at their last large party and dance, reflects upon forty years of marriage. Both he and the story create a love-struck image of a woman with a special type of strength that often does not conform to the given norms: “It was amazing what Regitze could and always had been able to get away with,” observes the husband. In her special type of autonomy, which also makes her the victor in many of the couple’s conflicts, lies a dream about a different order that is not subjected to pressure by groups, norms, or authorities, but that is also willing to compromise and interact with others. While the alternative values in most books are represented by the sensitive and the vulnerable, here they are embodied by the figure of a heroic woman who, in a way, is in league with the powers that make things – the marriage, the family, the circle of friends – work. At the same time, she represents a loss and an absence in the novel, which is composed as a frame-story in which the last dance foreshadows her approaching death, and her values become more pronounced by virtue of the absence that her presence also indicates. Everything good has been here, as an image, and it is painful to think that it will one day disappear.

Martha Christensen published a score of novels and short story collections in the period between 1962 and 1995, with many reprinted in paperback. Her biggest success, Dansen med Regitze (1987; Eng. tr. Memories of a Marriage), sold more than 100,000 copies.

Positive strength is rare in Martha Christensen’s work, which highlights the weakness of strength by pointing to the destruction it often wreaks. As a critic of the system, she is a moralist rather than a politician: her object is to demonstrate the mechanisms that work in the social systems and their representatives in order to contribute to the self-awareness of the system itself.

Throughout Life

Dea Trier Mørch’s writing takes on the ambitious project of mapping the important stages and crises of human life.

Dea Trier Mørch was educated as an illustrator, and her debut was in the form of two illustrated reports, Sorgmunter socialisme (1968; Tragicomic Socialism) and Polen (1970; Poland). Her journey to the Soviet Union on a study scholarship in Sorgmunter socialisme is a journey of the soul, in which the traveller desperately and futilely attempts to penetrate the Soviet state apparatus to find the Soviet soul. It is not until she is on the verge of suicide, as sickness and fever commit her unconditionally to the foreign system, that she finds love and care within the Soviet state. This sixty-eight-page story is written and illustrated at the crossroads between the individual sense of alienation and the demand for freedom and love, and the collective socialism with its disciplined demands on artists, guests, and subjects.

Eighteen years later, it is a more distant and, literally, mapping illustrator and writer who travels west, and especially to New York in Da jeg opdagede Amerika (1986; When I Discovered America). She gets to know the big city on foot and tackles the city’s size and immensity by specifying the number of hours it takes, just as all routes are inked in on sketches of maps. New York gives rise to both fascination and criticism, and these ambiguous feelings can be read in the book’s form, which alternates between impressionism – a torrent of observations – and reflections, especially on poverty, exploitation, and racial conflicts.

The long journey from 1960s Soviet Union to 1980s USA is also a political journey. In the 1970s, Dea Trier Mørch was a member of the socialist artists’ collective Røde Mor (Red Mother). Her commitment to Communism pervades her entire production of images and texts, and when she resigned from the party in 1982, her political and analytical approach to the world had not changed. Dea Trier Mørch still wanted to see life in its connections. Her oeuvre is positioned in the crossfield between the perceived, impressionist detail – which gives an idea of the individual’s psyche, of the passion, sensitivity, and pain – and the giant, well-composed outline that brings out grand narratives and images.

America is discovered, but the country does not become an existential crisis; only Harlem manages to get under her skin: “The road through Harlem is a road of passion”.

Vinterbørn,which was adapted to film in 1978, marks the beginning of a series of narratives about life’s hot spots from birth to death. What makes these stories special is the care and discipline with which they approach all these fundamental stages of life. Problems, crises, and disasters, themselves, are never permitted to overshadow the process. Instead, conflicts and grief are dealt with, revealing in the process a possible path to survival. The illustrations, with their clearly delineated expanses of black and white, emphasise a visualisation of the characters that is equally far from the sketch and the detail stage, the manageability, and the strength as parts of the books’ project. She creates coherence between the stories by having the characters reappear. This method makes the society she is describing more manageable; the world becomes a holistic entity. The women in Vinterbørn, Den indre by (1980; The Inner City), and Morgengaven (1984; The Morning Gift) become, to a certain extent, subordinate characters in each others’ stories: together, the educator, the workman, and the artist form an important trinity in Dea Trier Mørch’s universe of social care, class-consciousness, and artistic calling.

Lulu in Den indre by feels existential angst and a desire for the self to simply disappear:

“Lulu is not afraid of anything that comes in any form from the outside – that has to be fought by people at once. What she fears – is the terrible self. And what it might do. Hell is not the others. It is yourself. […] Walks back and forth a couple of times. Wishes that her self would disintegrate and disappear and never have existed. And just be sucked up and mixed with the dust of comets in their great, elliptical orbits.”

The wholeness and coherence also come from a political fellowship that is based in the Communist Party, of which Dea Trier Mørch was a member from 1972-82. The Party is central in Den indre by,where it becomes one of the factors that divides the busy families in a daily life in which they, in addition to work and caring for the children, also have all the meetings to attend. But it also becomes a meeting place, a framework for the solidarity that becomes an important counterbalance to the crisis in the private sphere.

In Kastaniealleen (1978; Chestnut Alley), family history forms the framework for security and continuity, while the in-between generation has practically disappeared from the story about the relationship between the grandparents and the three children on a visit one summer shortly after World War II. Life with the two old people puts history out of play: it becomes at once both valuable experience and a confined space which the oldest of the children, a seven-year-old girl, is on the verge of breaking free from.

In Kastaniealleen (1978; Chestnut Alley), Dea Trier Mørch wrote about childhood and the relationship between grandparents and children. In Den indre by (1980; The Inner City), the focus was on the private and political life in Copenhagen. Morgengaven (1984; The Morning Gift) is about the relationship between art, children, and sexuality in a woman’s life. Skibet i flasken (1988; The Ship in the Bottle) deals with her early childhood, and Landskab i to etager (1992; Landscape on Two Floors) with love between adults, while Aftenstjernen (1982, Eng. tr. Evening Star) is ultimately about death.

Much later in her career, Dea Trier Mørch provides a supplementary, and much harsher, image of the early childhood in which the little girl not only acquires language, gets to know the adults around her, and obtains her first impressions of the world, but also acquires a deeper social and personal insight. Skibet i flasken (1988; The Ship in the Bottle) takes place in the final years of World War II, where the three-to-five-year-old girl lives in Nyhavn on the Copenhagen harbour with her mother, who is an architectural student, and her new little brother. The political narrative moves from tension to a liberation that puts an end to the fear. However, the family narrative is much more complex. The mother has the two children with a married man who ends their relationship after the war. And the little girl has to learn to live without a father, which, among other things, makes her an outsider in her kindergarten.

The girl’s survival strategy contains the seeds of Dea Trier Mørch’s artistic technique. She copies the world in her drawings in order to learn about and master a complicated life. The novel depicts the vulnerability in detail and without drama. It is built up of the many smaller images of the story which, like the delicate lines of the etchings in Sorgmunter socialisme, become an expression of a sensitivity that can lead to mental collapse, the loneliness of the individual, as in the Soviet Union book, but can also become the protection inherent in copying the world, which is conquered through images and words. Skibet i flasken also becomes a symbol of the necessity of the artistic process, which restores the individual to a wholeness, more specifically to family, friends, a political party, and symbolically to a holistic interpretation of life and history. Without it, without the will to become connected to the whole, the individual disappears into the cosmos.

The detachment process therefore becomes extra complicated in the novels, just as it does for the son in Aftenstjernen (1982; Eng. tr. Evening Star) as he cares for his mother, who has cancer. In the face of death, everyone is on the threshold of loneliness, of being excluded from a meaning and a community. The son, who loves his sick mother, also experiences her demands as a threat to his entire existence, his work, his new love affair, the needs of his children. He grows angry with his mother, but the anger also helps him escape the symbiosis. In the works of Dea Trier Mørch, death is often closely connected to life: the little newborns in Vinterbørn exist in a hinterland between life and death; children and old people both exist on the fringes of history, of time. On this plane as well, her stories move between life’s power centre, where people work, love, care for children, and involve themselves in politics, and the periphery, where the experience of the essence of life is both stronger and associated with greater vulnerability. On life’s outer edges, this is felt most intensely. It is where the fear is, the depression, the sense of vulnerability that is artistically associated with the detail and with impressionism’s sensitive perceptivity. In midfield is daily life and common sense, which can be comprehended with simple lines, images that make up a coherent whole.

The balancing act is also characteristic of the epistolary novel Landskab i to etager (1992; Two-Floor Landscape). Here it appears in the crossfield between the artistic, ambitious form of the novel and the vulnerability and pain that characterise one of the letter writers. It tells the story of a long-distance relationship between the author and illustrator Nana, who is in her mid-forties, and the somewhat older German physicist Lennart. The letters themselves become a symbol of the relationship’s problems. They are written in the distance and absence between the two. They recall and plan and account for the lives they have separately. The conflict is complicated by her need for closeness and his for more distance. And as the story progresses, the relationship fades out more and more; the letters become monologue reports from the two separate lives. Through a number of artistic references, the story is written into a larger pattern, a whole that together with political involvement, social network, and children, provides the necessary balance to the fragile love affair on the verge of separation and fragmentation. This unfinished tension cannot be overcome – it stands as the basic condition for life, and for Dea Trier Mørch’s artistic production.

A Woman’s Wrath

In Anne Marie Løn’s story about the tabloid Vor Tid (VT; a pun on the name of the large Danish tabloid BT),the young journalist Vera Johansen kills her employer by throwing a beer bottle that hits him in the head. The name of the novel is Veras vrede (Vera’s Wrath); however, the wrath does not belong to Vera alone. It could be the title of many of Anne Marie Løn’s works, which feature indignation and strong moral involvement. Vera is angry at the cynical and well-adjusted editor to whom the female victims in the newspaper reports are unimportant as people, but worth their weight in gold as objects and commodities, and the novel sharply attacks the world of journalism in which sales and readership figures count for more than any kind of journalistic ethics. She pushes herself to the limit in order to write and act responsibly within the framework, but finally throws the bottle “in complete desperation” and thus finds harmony within herself.

Vera is taken to the prison in Ringe, on Funen, and with her, Anne Marie Løn also leaves the city and begins a series of stories about people in the provinces and rural towns, which is a logical consequence of Vera’s rebellion. She is now writing journalistic texts and novels from provincial Denmark. In the city, life and work are divided, as are commitment and necessity, emotions and profit. In rural life, which she does not confuse with an idyllic life, there are elements of coherence between life and work, between man and woman, between earth and people. Taking this possible coherence as a point of departure, Anne Marie Løn continues the story of Vera’s wrath.

The dream of another world has been present from her debut novel about the eternal student from France, Maurice, in Hvorfor hvisker I til mig (1977; Why Are You Whispering to Me), and it is a theme in a number of her novels based in and from the point of view of provincial Denmark, especially in the Northern Jutland region. From here, she tells the story of a life for which the modernity of the city lacks the experience and the language.

This other life is described as early as 1984 in Fodretid (Feeding Time), a story about the catastrophic consequences of rationalisation for a farmer who, encouraged by the European Community’s directives and advice from experts, restructures his production into modern hog farming. This turns his farm into a factory, the coherence of his life falls apart, and when the benefits fail to appear, the man accepts defeat and stops feeding the animals. However, within the scope of the provinces, with roots in history, people are also fostered, heroines who can choose and endure their fates, such as the strong heroine Thyra in Traktørstedet (1985; The Beer Garden) and Café Danmark (1987; Café Denmark). She works and lives through the final years of World War II by serving a group of airfield workers who indirectly work for the Germans. Thyra becomes an encroaching image of coherence and fate. As a widow with four children, she lives a life of hard work that is further enriched by a love affair with her younger boyfriend who brings two more children into the ménage. In a way, she gives birth to a score of men and children; she loves and she defies the distrust of her surroundings. She manages to unite independence, motherliness on a large scale, and sexuality in an unrealistic utopian life.

The criticism of rationality continues in 1988 in Den sorte liste (The Black List), about yet another farm in dire straits, albeit with a chance of survival. The threat to the family that lives with rather than by the farm, the crops, and the animals comes from the outside – from interest rates and the European Community. However, they clash with inner conflicts about values and morals, about visions of humanity and fate. In the end, myth and fate take over the story and become the overriding connection that makes life on the farm meaningful despite the financial and political problems.

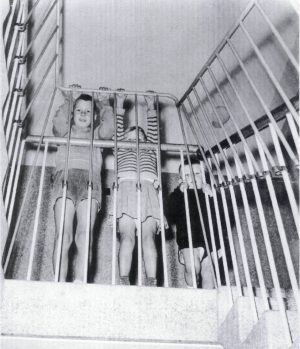

Anne Marie Løn also finds a meaning beyond the city’s fragmented and commodity-fixated life in the special culture that exists in circus life. Det store nummer (1992; The Main Act) tells the story of a life in which work and private life flow together and where the extended family is the basic lifeline for the trapeze and acrobatics group we follow. In the extended family, there is room for everyone, even babies, the injured, the pregnant, and those too old to perform. The children and the growing bellies are the future performers, while the old people take care of the reproductive and administrative jobs. The extended family also departs from the closed circle of the nuclear family by being able to take in children who are not biologically part of the family. In short, the troupe becomes a beautiful image of an ideal society that makes a break from urban modernity’s destruction of the community, of zest for work, of respect for the body as a vessel of work, love, and birth, and of the passage of time, of days, years, and life. Into this utopia, Anne Marie Løn then inserts a conflict that grows out of this exact type of family, with its matriarchy and its limits. A daughter is attracted to the modern freedom to choose whom to love and to having an influence on her work. Before the mother/daughter conflict comes to a head, however, Anne Marie Løn allows it to be resolved by presenting the daughter’s decision to remain in the group as her free and autonomous choice. In this way, Anne Marie Løn also loosens up the conflict between the ties of tradition and modernity’s promises of an individual career, which crumble away. The mother figure is permitted to remain unchallenged as the guarantor of continuity and coherence; the modernity that Vera abandoned is not permitted to infiltrate as a serious alternative.

In the radio novel Sent bryllup (1990; Late Wedding), the heroine, eighty-four-year-old Edith Tønnesen, is the incarnation of the special mixture of autonomy and motherliness that becomes a main theme in Anne Marie Løn’s universe. After an unfortunate fall in the woods, she lies there for six days, recalling a life that points towards a universal and mythical meaning. The contrast between rural and urban, between motherhood and career, disappears in the void between the forest floor and fate.

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd