In 1987, The Literature Committee of the Danish Arts Foundation, headed by the reviewer Marie Louise Paludan, awarded its three-year grant to the poet Birthe Arnbak (born 1923). Birthe Arnbak made her debut back in the year of peace 1945, so it was an elderly, experienced poet with a long list of accomplishments who was given appreciation and reward, and for the first time the chance to devote all her time to her literary work.

Since 1945 and her debut collection Spejlet (The Mirror), Birthe Arnbak has published work after work every few years with the exception of a seven-year interval around 1960, the years when several groups of young modernists broke ties with the dominant late symbolism in post-World War II poetry and paved the way for a thematisation of body and gender that rattled all customary notions and the lyrical language as a whole.

In many ways, Birthe Arnbak and two of the most prominent poets of her generation, Grethe Heltberg (1911-1996), who made her debut in 1942, and Grethe Risbjerg Thomsen (1925-2009), who made her debut in 1945, were trapped by this budding new modernism, which quickly came to include a number of women writers whose aesthetic experiments had a significant influence on the following decades.

The slightly older poets Tove Meyer and Tove Ditlevsen reacted to the young, modernist challenges by honing their expression and universe, resulting in poetry that both lives up to and departs from late symbolism. This happens in major works such as Den hemmelige rude (1961; The Secret Window) by Tove Dilevsen and Brudlinier (1967; Fault Lines) by Tove Meyer. Titles which initially signify an aesthetic that approaches a secret, unseen place in a universe and the fault lines in a poetic work. Artistically, both Tove Ditlevsen and Tove Meyer moved in a new and particularly exciting direction which went unnoticed by literary critics until much later. In 1988, Asger Schnack published a brilliant collection of Tove Ditlevsen’s poetry, and Poul Vad published an essay on Tove Meyer’s poetry in the literary journal Den blå port (The Blue Gate) in 1987.

In the essay “The Trip to Norway”, Thorkild Bjørnvig talks about the breakthrough of modernism:

“On 2 February 1961 … four Danish poets sat at a table in the restaurant on the Oslo ferry. They were Tove Ditlevsen, Halfdan Rasmussen, Klaus Rifbjerg and myself. I was in a bleak mood because it was my birthday. In Denmark, modernism was just breaking through, and soon there was a heated discussion between one of the most ecstatic, confident, and fanatical advocates, Klaus Rifbjerg, and the traditionalist forties, us. Tove claimed that she had many unreleased poems but that she had lost interest in publishing them because there now seemed to be some sort of a ban on poetry featuring regular rhyming verse. Halfdan was on her side. Klaus said that it was rubbish, but the fact of the matter was that the days of rhyming verse were definitively over, and thank God for that. Both Tove and Halfdan flew up, while I tried to look at the case from both sides; what is said on such occasions is rarely worth remembering; In any case I insisted on the right to rhyme and encouraged Tove to grow a thicker skin and get her poems published. It was late by the time we hit the sack.”

Harald Mogensen (ed.): Om Tove Ditlevsen, (1976; On Tove Ditlevsen).

Some of the younger late symbolists had the same reaction to modernism as Birthe Arnbak, initially staying quiet and then continuing on their own paths. Others took a sharp, critical tone in their art, such as Lise Sørensen (1926-2004), whose biting humour and exposure of the literary gender roles was already felt in the 1950s and really took off in 1964 in her debate book Digternes damer (The Ladies of Poetry).

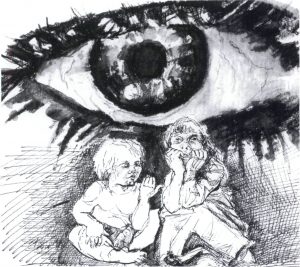

In general, 1964 was an interesting literary year for women writers who made their debuts in the 1940s. Grethe Risbjerg Thomsen takes stock of her project in Udvalgte digte 1945-1964 (1966; Selected Poems 1945-1964). Cecil Bødker (born 1927) is particularly radical in her poetic survey. Samlede digte (Collected Poems), containing the poems the author “wants to preserve from her precious collections”, was published in 1964, a few years after Cecil Bødker made a name for herself in prose with one of the most widely read post-World War II collections of short stories Øjet (1961; The Eye), in which she breathes new life into psychological realism, linking it to mystical modernism.

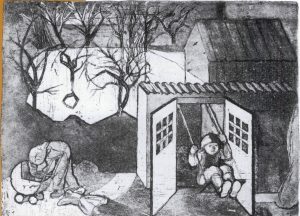

Characteristic for late-symbolist women authors is the use of the child and childhood as an important metaphor. The presence of the child as a figure and metaphor simply calls attention to the fact that something can be seen, understood, and sensed. Poems with titles such as “Den ensomme Pige” (The Lonely Girl), “Små Børn” (Little Children), “Vuggesang” (Lullaby), and “Til et Barn” (To a Child) stem from Grethe Heltberg’s many different collections and are typical for the poetry of her generation.

My childhood is a spring

I can always tap into:

it has not become memories it is a reality.

– writes Grethe Risbjerg Thomsen in the poem “Min barndom” (My Childhood) from the collection Vort eneste liv (1964; Our Only Life). As in reality, the child and childhood are closely associated with art and with death. Childhood and the child are not a memory, making it a more or less clarified, overcome, and interpretable phase in life. Childhood is here and now as a constant possibility, a demanding mode of experience that is ever-present and that established a dialogue with both creation, in the form of art, and cessation, in the form of death: “But not until I die do I disappear completely / in my deep torrent of happiness”, Grethe Risbjerg Thomsen concludes in her poem “Min barndom”.

Many of her poems turn on a dead child who appears in a clarified and aesthetic light, perhaps because the child in this figuration unites art, creation, and death. The verses about dead children sound melodic and sweet, like Holger Drachmann’s poem about the dead Snow White, and contain no references to world war and suffering. Everything is mild hints and mysterious insight. In Grethe Heltberg’s poem “Du kom fra det store Intet –” (You Came From the Great Nothingness –) from the collection Døden og Foråret (1943; Death and Spring), the child is released from “the chains in which life had bound you” and the parents ask:

Child, do you still remember

us who lent you life?

Are you happy to again be free?

The child and death become such common rhetorical figures for many of the late symbolists that a portrait poem of a daughter who is very much alive by Grethe Heltberg actually begins with a dream that the child is dead: “I dreamt that you were dead my Love, / that you were dead and that everything was long ago …”. It is not until she is dead and in the past that the girl can be seen and depicted as living, and the poem is filled with her childhood, light laughter, and reassuring breathing.

Reading the poetry of the post-World War II years often calls to mind the girl portraits of Holger Drachmann’s “Jeg hører i Natten den vuggende” (I Hear in the Night the Rocking), Sange ved Havet (1877; Songs by the Sea), with its middle stanza:

I see in the night the dazzling

Vision of a white-clad child

With wax-pale cheeks,

Who lures, who reminds,

Who lights my brow afire,

Turns my heart to ice.

The calm brushes above the eye,

And the hands folded

Across the chest like a child.

From the bosom which rises chaste and pure,

Slides a green oleander branch;–

Wherefore did the voices say:

Snow White, Snow White, you died!

In the works of Birthe Arnbak, the child and childhood recur in new variations on the theme of the connection between the child and art. The collections Morgenstund (1975; Early Morning) and Forventningens land (1985; Land of Anticipation) capture a childhood universe in short narrative poems, but not as memories – always as a living source of inspiration and artistic emergence. “When I speak of childhood / it is of love that I speak …” she writes in the final poem in Morgenstund.

Even though this generation’s youth and artistic emergence occurred in the final years of World War II and the subsequent period, the end of the war and the threats of the Cold War seem only to have had a limited influence on their writing.

The poetic universe is ripped by a sun that turns to blood and fire in Grethe Risbjerg Thomsen’s poem about the atomic bomb in “Morgen i August 1945” (Morning in August 1945) from De aabne Døre (1946; The Open Doors), and childlessness is a recurring metaphor for the absence of meaning and existential crises of post-war life in the poem “Ventende Ager” (Waiting Field) from Natten og Dagen (1948; Night and Day):

I am a waiting field,

where no grain will grow.

I am the childless mother,

a faithful without faith.

My longing is unrequited,

but never burns out.

I await a miracle,

I seek a foreign God.

In a later collection, Ingenmandsland (1989; No-man’s Land), Birthe Arnbak reflects on the past in a poem entitled “Under krigen var det også sommer” (During the War there was Also Summer):

There was also summer

during the war,

summer between winters,

oppressed by cold,

foreign fear, and sorrow.

Our first summer

was like the fairy tale’s

inverted hidden world

under the brook,

green, lush meadows,

sun-warmed profusion of flowers,

quaking grass …

Often the verses and stanzas of the late symbolists are filled with growth and moisture, with flowers, smells, shade, and grass in a copious abundance and sweetness; the metaphors intertwine in dim light, when scent and quiet suddenly take on new meaning, as at the end of Grethe Heltberg’s poem “Skyggen i haven” (Shadow in the Garden) from Pigen og evigheden (1952; The Girl and Eternity):

… The scent of roses and pale red peonies

floats by under the apple tree branches.

Quiet. The acacia treetops wave and bow

under the grey-white clouds, alight in the late

glow of sunset like pale red peonies.

Cackling hens. Sunshine and summer happiness,

Fenced idyll in a rural, innocent garden.

Quiet. But lurking quiet. And no one is safe;

The scent of roses is sweet like the smell from graves.

War in Korea. Across the grass a shadow falls …

In Grethe Heltberg’s poem “Skyldfri” (Guilt Free), from the collection Pigen og evigheden (1952; The Girl and Eternity), images of the Korean war penetrate daily life:

… Korea – children suffering

The old pain passes,

a train that slowly advances,

dusky through her mind

with bleak poetry.

She puts down the magazine

and turns to her hairdresser;

It’s terrible that hate

and selfishness always grow,

and children innocently die!

Then she smoothes her dress

she knows she is guiltless, pure, and true,

and steps out into the sunlight,

home to her own children

and her third husband …

The Burning Trace of Fire, a Rebellion

While the Korean War casts a shadow over the surging growth of Grethe Heltberg’s poetry, war, racism, and neo-imperialism become prominent themes in Cecil Bødker’s writing. Sometimes she shouts in admonitory, bombastic words about egoism, prejudice, and possessiveness, sometimes she plays with teasing little poems, but most often, the writing seeks to recall and rearticulate humanity’s ancient myths, to transform the myths into living possibilities and answers. They appear in her poetry as portrayals of trials, promises, and release. Myths about creation, destruction, and returning are repeated in the poems in different variations, often strongly resounding with the hope of a new beginning, as in the poem “De langsomme glæder” (The Slow Pleasures) from Anadyomene (1959):

… But someday

time will come to us again

only full of its slow pleasure,

and the speed will be lost out in space.

Throughout centuries

a fire burns in the quiet night

near a mountain of gnawed bones

and new pots full of grain

will contain a meaning. And planets graze in the distance

in a new beginning

full of decaying myths of destruction.

Humanity must attempt to rediscover its own roots in myth and in life, to let go of the need to understand and make room for the ability to experience. Imbalances in life and the world are the results of old sins like pride and greed, and of a transformation of time from a dimension in which we can experience patiently flowing life to a dimension that drives us forward in rapidly changing desire. The myths are about the emergence of the imbalance between the sexes and the return to life that could come from the sea, the woman’s element, after fire, the man’s element, has burned the world to ashes. Even though the contradictions in this gender topography initially seem clear-cut, images and ideas still permit the enigmatic and ambiguous. Woman and man both have a part to play in the beginning, the desire, and the re-emergence when the sea, like Anadyomene, rises – brutal and bitter, and time will “burst and flow … between the core and the everything”. In the eternal cycle of emergence and re-emergence, humanity exists as man and woman, and with a desire that not only begets life but also death, when the descendents of man and woman become strangers to each other. Cecil Bødker’s poems are characterised by a great effort to draw parallels between mythical time, the present, and the future. The poems are often insistent, rhythmically admonitory, and heavily suggestive in their attempts to breathe life into the ancient fire of humanity.

This smouldering

deep in your memory’s black happy holes,

this ember

still in the corridors under your day,

and behind the gate you cannot close

your heathen night.

And in the hidden forbidden places

and in the steep secret spaces under the floors

in your interior,

this house of necessity,

still the red glow of a happiness,

still the burning traces of a fire,

of a rebellion …

– she wrote in the poem “Under de omvendte både på stranden” (Under the Overturned Boats on the Beach) from Anadyomene (1959).

However, the heavy, lyrical rhythm is also broken by light, fantasising verse in which the child is placed at the centre of a world, as is the case in both the first collection, Luseblomster (1955; Autumn Crocuses), and in the conclusion of the early lyrical piece, the suite of poems “Lytteposter” (1960; Listening Posts).

Boy

Live in hill

Sleep in heather root

and birdsfoot,

Grasshopper month

heathberries in your grey-black sand.

Live in hill

Find yourself reborn

with elevated senses

turned towards the close night

like newly sharpened lances.

Cut off fir wall’s wings

at the base

with naked knives,

force the insecure eyes to lock,

awaken, and be alive.

Grasshopper month

awaken in your grey-black sand

with sap on your cheek

and the caveman’s

vigilant listening to the wind

Cecil Bødker: the poetic suite “Lytteposter” (1960; Listening Posts).

The tension between the deep thinking and the delicate images in the poetry of Cecil Bødker appears in new variations in her prose. The narrative mode turns out to have the ability to both transmit and unite the mystical material and the intimate sensations. The short stories in her first work of prose, Øjet, are surprising in the way in which they connect myth and reality. They can be compared to Martin A. Hansen’s use of myth in his stories in Agerhønen (1947; The Partridge); however, Cecil Bødker always adds to the myth a sensual everydayness or allows it to be split by a broken and alienated consciousness. An ancient anxiety and protectiveness takes on mythical form in the elaborately realistic story “The Bull”, about a mother trying to save her children. Often her stories are set on the edge of the unknown. The characters are forced to cross boundaries and accept the conditions of a doubtful survival, they are confronted by powerful outer and inner forces which allow the time and dimension of the myth to take form. “All considerations were lost, all conditions pushed aside by a situation greater than words and curses. – She was willing to die in order to kill,” it says about the mother.

The stories are often set in an ‘after’ universe, after the bomb and catastrophe, as in the story “Chaffinch” about a dying boy unable to comprehend that he can see but not hear the bird sing. “And that was what happened. Now it was afterwards. He tried to recall how it had been, but couldn’t, only knew that it was over”. The Cold War’s ever-present anxiety holds the stories in an iron grip, and Cecil Bødker addressed that anxiety psychologically, socially, and existentially with such success that the short stories became required reading for the generations of schoolchildren who were taught at school how to duck and cover in the event that…

Her work continues to search and test genres, first in the form of a radio play Latter (1964; Laughter), and the following year in the form of the experimental novel Tilstanden Harley (Condition Harley) about a broken consciousness form associated with the epitome of post-war culture: the motorcycle, which causes the young male main character’s both concrete and rather symbolic skull fracture. Tilstanden Harley leads the reader into a universe in which familial relations and gender identities are blurred or confused, and male existence has become a deadly restlessness which liberates itself unscrupulously from the woman and child.

“And afterwards there was the question of what they should call him since he didn’t have a name? Whatever they want. Come up with something. He’ll probably leave again before too long anyway. Always the same surprise because he is nameless. Alberte, who pretends like it’s nothing, and the old father, who moans and groans over all the unbelievable stuff he hears. It is about time to sit down at the table in this peculiar house where the father is the mother to a son who is a daughter or the other way around. It’s certainly not something you talk about.”

Cecil Bødker: Tilstanden Harley (1965; Condition Harley).

The cultural criticism which permeates these early works, and which is expressed in an intense search for form, is also central in Cecil Bødker’s later works, where she achieves success with, among other things, stories and novels for children. She does not operate with a sharp distinction between literature for children and literature for adults. The stories that have become popular among children are certainly not lighter than the important works for adults she produces later in her career, such as Fortællinger omkring Tavs (1971; Stories of Tavs), Evas ekko (1980; Echoes of Eve), Tænk på Jolande (1981; Think of Jolande), and the continuation of the Tavs stories Vandgården (1989; The Water Farm), Malvina (1990), and the short stories Tørkesommer (1993; Drought Summer).

In her children’s stories, the complicated use of metaphor is toned down and an engaging storyline takes the foreground, but the main thematic and artistic methods are the same: an everydayness that is broken up and illuminated by mythical motifs or a mythical universe that is broken up and illuminated by an everyday world. The child and the mother-child constellation is always loaded with powerful and urgent mythical value in the work of Cecil Bødker. In relation to the late symbolists, however, the idealisation of the child has given way to an experience of childhood and motherhood as concrete and animated existence, and in time to a more open and direct narrative style. The child often appears as an outsider or rebel who insists on life’s simple values, and the child communicates the criticism of modernity and search for other lifestyles which is so important in the work of Cecil Bødker. The outsider-children and mothers include, in particular, Jesus and his mother Mary, whom Cecil Bødker portrays in the Marias barn (1983-1984; Mary’s Child) novels.

Cecil Bødker’s very large body of work includes several series of children’s books, of which the most famous is the excellent Silas series, which she began as early as 1967. The stories about the runaway boy Silas and the black mare address such themes as coercion and oppression and an alternative, free, and authentic way of life. It was followed by the Jerutte series, which began in 1975.

One of the high points of her literary career is Salthandlerskens hus (1972; The House of the Widow Salt Trader), which Cecil Bødker wrote after a three-month stay with the Ethiopian salt trader’s widow Debiteh Gole and her family. Salthandlerskens hus is a remarkable and innovative book in every way, in which the themes and ideas from her entire body of work find a new expression and challenge. Cecil Bødker succeeds in creating a reflective prose that permits both closeness and distance. She uses a ‘you’ form in which the author addresses herself, reflecting on her expectations of the meeting with a foreign culture and the new dreams, hopes, and surprises elicited by real life in foreign lands. The debate back home in Denmark at the time about the so-called underdeveloped countries or the third world had, albeit with the best intentions, many condescending undertones, and in contrast to this, Salthandlerskens hus reveals a human openness that seems liberating because of the author’s willingness to acknowledge her own uncertainty and many prejudices.

“Widow-with-nine-children – that was all you knew about her beforehand. Not what she was like, not even her name or where the village was …

“… you formed an image in your mind’s eye, and before even leaving home there was a negro matron with long, hanging breasts buried in your anticipation. The myth of Africa which you have been fed by other images and through your reading. The myth of the Widow-with-nine-children. You did not formulate it as a clear thought, but the sense of the negro matron was still intact when you stood up in your house and walked out to greet her.

“The grass was very green and bitten off extremely close to the ground, and petite, slight and erect, Nefertiti and the queen of Saba in one and the same person, came walking across the bitten grass. And within you, the negro matron collapsed and left you alone in front of the Hamite Debiteh. And you felt this was something you should have known.”

The portrait of the widow salt trader is respectful and loving. The meeting with the Hamite is first and foremost a meeting with an enchanting female dignity and stature; Debiteh lives her antiquated life on the edge of the vanishing of time and of the beginning and end of life, and she manages to use the powers and possibilities she has at her disposal with great care and ingenuity. She acts with great consideration to protect the lives of her children. She is rooted in the old Africa, but cautiously and openly accepts the possibilities that can benefit her family. Her entire way of life and attitude fundamentally challenge all the usual old preconceptions about developing countries and their native populations. Cecil Bødker does not idealise the antiquated Ethiopian life, but as the author feels the effects of the ancient lifestyle on her own body in the form of the loss of her usual sense of direction, extreme stomach pains, and a basic feeling of hot and cold, she considers an alternative view of life and progress:

“The art of living could become fashionable as a status symbol. Not the bare-bones existence of the developing world where you die with just the slightest bit of bad luck, and not the excessive consumerism in which you have no time to live, only time to hurry along.

You hold the key to a third option buried in your consciousness as this inescapable place bores its way into your body.”

Salthandlerskens hus, with its portrait of Debiteh and her children, coalesces around the notion of a third way of life, as a “rough and rank” myth about woman and about Africa. All idealisation is gone, leaving only strength and the ability to survive. “She was your Africa. The essence of your entire stay.” However, a few months after the end of Bødker’s stay, Debiteh died, the victim of what turned out to be a ritual murder of that proud and self-reliant person.

Her children were spread to the winds, their ancient life abruptly coming to end in their meeting with European schools and families, just as the widow salt trader hoped and wished on her deathbed. Cecil Bødker adopted two of the widow salt trader’s daughters, thus connecting life to myth with highly tangible problems and possibilities as a result. At the end of the book about the widow salt trader, the story of the meeting of the two Ethiopian girls with their new family, country, and climate is already under way. Salthandlerskens hus was a huge success; however, Cecil Bødker’s novels from the 1980s, especially Evas ekko, have also been viewed by many as a new direction in her career in the wake of the women’s debate of the 1970s. Evas ekko is about the woman Louise, who has had her fill of marriage and playing the woman’s role. She seeks myth and adventure on her journey out of modernity, and rediscovers herself and her whole life in the process. Hidden behind the life of Louise is the myth of Eve, and behind the Eve myth lies the rebellious, independent Lilith in the form of the mender Timiane, with whom Louise moves in. However, she does not let go of the Eve identity until the end, when she takes in an ugly little foundling and continues her wanderings on earth. The novel is not really as dramatic a shift in her work as many claim. It is much more a continuation and expansion of the themes and the criticism of modernity that have always been important in Cecil Bødker’s writing.

A sharp criticism of modernity and a responsiveness to nature and myth are also expressed in Cecil Bødker’s poetry collection Jordsang (1991; Earth Song):

Gone

But gone is just somewhere

else

gone is not really gone

only temporarily out of sight

in the belly of the earth

at the bottom of the sea

or up in the clouds.

Everything is still there

everything exists still

and mercilessly it

returns

to our way

of doing things.

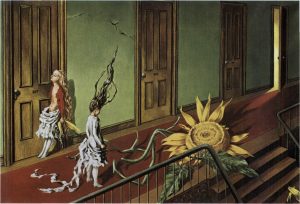

Exit Snow White

Mallow, Lizzi (b. 1937) (da.): Sengen, 1978. In: Lizzi Mallow, exhibition catalogue by Bent Karl Jacobsen, Galleri 22, 1979

Whereas Cecil Bødker’s writing embraces modernism in the way she works with form, cultural criticism, and myth, Ulla Ryum (born 1937) takes as her point of departure the experimental modernism of the 1960s. And the new direction uses language and imagination in an entirely new way, going beyond normal limits, making room and opportunity for exploration of the relationship between the sexes and post-war womanhood. The work of Ulla Ryum quickly turns towards drama, which she influences with her own comprehensive production, with her research in the dramatic arts, and with her efforts as a director and course instructor for young dramatists at the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DR).

Ulla Ryum’s body of dramatic work comprises a series of pieces written for practically any stage in Denmark, from large theatres to radio theatre, TV theatre, small amateur theatres and experimental theatre groups. One of her most important pieces is the cycle comprising Den bedrøvede bugtaler (1971; The Sorrowful Ventriloquist), Denne ene dag (1974; This One Day), Myterne (1975; The Myths), Krigen (1975; The War), Jægerens ansigter (1978; The Hunter’s Faces), and Og fuglene synger igen (1980; And the Birds Sing Again), published in the compilation Seks skuespil (1990; Six Plays). She has also conducted research in the dramatic arts, resulting in a PhD thesis entitled Dramaets fiktive talehandlinger (1993; The Fictive Speech Acts of Drama). Additionally, she has shown keen interest in the debate on women’s aesthetics and women’s language, with a number of her articles on the subject collected in Kvindesprog – udtryk og det sete (1987; Women’s Language – Expressions and the Seen).

Ulla Ryum’s debut, however, was in prose with the novel Spejl (1962; Mirror), wherein a character gallery of allegorical variations on the themes of alienation, loneliness, love, and egoism is eventually confronted by themselves, face to face. The slightly heavy, complex arrangement plays out the motto from the Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians about love that bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things, and about the person who sees in a mirror, dimly, and fulfils a daring attempt to find a new point of view on life in a world of war and post-war. Her works of prose are both dramatic and fantastically imaginative in their analysis of the relationship between people and the longing for love. The female characters often occupy revealing tragicomic positions: as avengers of self-sufficiency and self-righteousness armed with toy guns in Spejl, as a dying heroine in a coffin of her own choosing in Natsangersken (1963; The Night Singer), as a fallen tightrope walker in Latterfuglen (1965; The Laughing Kookaburra), and as a sawn-off giant lady in Jakel-natten (1967; The Harlequin Night).

A subtle and revealing humour pops up throughout her work, often in the form of intelligent black wit or popular grotesques. Ulla Ryum’s prose has often been read with far too much seriousness – a bubbling, revealing, or subtle laughter is often in play in her universe.

The aging, burned-out lush, the night singer who hangs out in the bars and lets people buy her drinks and who, in return, expresses wisdom, more or less, about life and death to the other sad lives, tells in her own warped and rather over-the-top manner truths about longing for love, betrayal and alienation. The mother/child relationship so often idealised in post-war literature is seen in the sharp new light of the night singer who says about her mother: “She took my shyness and shame, she pulled off my skin and examined me, tore me apart and put me back together in a special piece of furniture on which was written: ‘the love my daughter owes me for giving birth to her, for a breast sucked dry, for a saggy tummy, for thousands of hours in loathing with her father’”. The nightclub singer’s grand Snow White exit in a coffin accompanied by dwarves, and under the motto ‘Love yourself as your neighbour’ is a tableau of a woman’s life issue and a particularly cunning artistic commentary on the tendency of the late romantics to portray the woman as a decorative, dead child: “Snow White, Snow White, You died”, as the Danish nineteenth-century poet and dramatist Holger Drachmann wrote.

The novel Latterfuglen paints a both good-humoured and sharp portrait of the tyrannical, infantile husband of the day, Ludvig Mandelin, who cannot quite figure out whether his wife Hortenzia Rose has survived the vegetative life of the housewife, or whether she has taken a nose dive off the cornice while washing the windows and fallen to the ground dead as a doornail. In any case, Ludvig sets out to look for her in the land of the dead just as Orpheus looked for his Eurydice. Ludvig, who focuses traumatically on cleanliness and order, ultimately ends up like a child thrown out with the eternal bath/birth water:

“He appreciated their [the bathing ladies’] sense of order and felt one final faint pleasure in the fact that they would soon rinse the bathtub with care after him.

Nothing would be left of him. …

All three waved to him as the last of the bathwater flowed out, and as he floated away, he heard the distant clatter of their wooden sandals. Life had not failed him after all.”

“While Hortenzia’s memory was still warm, Ludvig Mandelin defined, so as not to forget any occurrence that could later turn out to be of greater importance than originally thought, the lines for his conscience to follow in the time that followed. He achieved, through intense work, a harmonious distribution between a sense of guilt over having failed and used her, and the confident knowledge of having been the only one who had understood her struggle and art.”

Ulla Ryum: Latterfuglen (1965; The Laughing Kookaburra)

The many short stories she wrote, of which several have been selected and compiled in Noter om idag og igår (1971; Notes on Today and Yesterday), pace back and forth across the boundary between a fantasy and an everyday universe. Scenes from the kitchen and hotel world where the author trained in her younger years play an important role, and the main themes are loneliness, longing for love, and loss – experienced and felt just as strongly and urgently by the nurses’ aid Miss Jensen in “Mrs Frederiksen’s Letter” from Tusindskove (1969; Thousand-forests), who loses her profoundly senile patient, and by the young couple in the short story “about the third child” in Noter om idag og igår. The couple argue and shout wildly and passionately at and past each other. She is expecting another child, or will she choose an abortion? – the short story executes a delicate and practically unnoticeable shift in point of view from man to woman, resulting in neither the man nor the woman “winning”.

The fantasy universe takes over in the popular story “The Flautist”, about a boy who saves his town from war and destruction with his wonderful flute-playing. His flute calls to birds from all over the world and pacifies the militant pirates who are forced to turn their ship around. The boy ultimately dies from exhaustion: “It had tapped all his energy, playing so the birds could hear as well”.

The dream, the child, and the artist are still powerful forces in Ulla Ryum’s writing, but in a manner more fantastic, imaginative, and anti-normative than that of the late symbolists.

The Child and the Text

For the young generation of modernists from the mid-1960s, which first and foremost includes Kirsten Thorup (born 1942) and Dorrit Willumsen (born 1940), the language and the child and woman symbolism move in other directions than for the early modernists Ulla Ryum and Cecil Bødker. Dorrit Willumsen’s debut, the collection of short stories Knagen (1965; The Coat-hook), begins with the long short story “Closed Country”, which depicts a childhood universe of a bewildering sensuality. The childhood universe is closed and abandoned, a world that can only be looked back upon in the past tense, although the metaphors can cause the childhood country to open up as an artistic reality. The short story begins with a list of objects that are gradually associated with sensory impressions of light, shadow, smells, and damp: “… the wallpaper – dark with shadow silhouettes. The upholstered chair with the pungent, mouldy smell – the mute, black-brown cabinet – sickly with mothballs and damp linen”. Out of the recognition of objects and impressions grows the description and the stories. Little pieces of a world are reported and take the foreground in startling correspondences between the child’s sensory impressions and the adults’ dialogue, enabling the perception of hidden psychological dimensions and links in this universe. In one of the fragments, the text associates the child’s experience of a dish of fancy cakes with the adults’ talk about different illnesses, bringing the entire conversation’s twisted and displaced body perception in focus. In Dorrit Willumsen’s work, the child is a catalyst of art, a probing and peculiar X-ray look at the adult world that allows metaphors to grow and unfold in unexpected and telling formations.

“The yellow cream slid in an even flow through the cracked cake. – Across the plate. – And a tiny bit dripped onto the tablecloth – making it look like a saturated bandage. As softly as funeral bells during the plague, the cream-covered forks tinkled against the porcelain. Under the raspberry mousse, I found a scabby, baked wound, I tried to pretend it was jam and put it in my mouth; but the acidic flavours stung the roof of my mouth. Aunt Antoinette’s almond cake was green from coagulated bile, and Nan sat there extracting an infected boil out of a butter-cream pastry.”

Dorrit Willumsen: “Lukket land” (Closed Country), Knagen (1965; The Coat-hook)

Among the surprising short stories in her debut piece is “Svangerskab” (Pregnancy), which compares a pregnant woman’s perception and sense of the foetus with a cat’s presence in her stomach. The short story moves back and forth between a clarity in the connection between foetus and cat and a liberation of the metaphor that sends it on a wild and free flight into a fantastic and grotesque vision:

“My prettiest pyjamas are torn up across the stomach – it was the animal – the catchild – which at one point demanded bronze-coloured silk. Now he spends our nights standing up on his hind legs in his painful confine. Wriggling. Scratching. Howling. … Sometimes the moon shines down on us – like very weak lemonade – my brain feels as sticky as candy floss, and once in a while a fun-fair-exhausted child nibbles at it”.

Dorrit Willumsen’s short stories voice an intense and fantastic exploration of and reflection on the language and metaphors of womanhood. They signify a break with the old artistic female metaphors which become important in the works of several contemporary, first-time writers, especially in Kirsten Thorup’s writing. In her debut poetry collection, Indeni – udenfor (1967; Within – Without), the language and metaphors are reduced to a budding minimum. The language forms little pieces whose slightest shifts in meaning are followed and investigated with heartbeats and the body as the parameters. The ‘I’ and the world lose their usual contours and dimensions, and the text grasps a narcissistic mode of experience that belongs to childhood.

Outside me

is desolate

the wind walks

over me

I steer awry

towards green leaves

– without the body

few tones would

be heard –

I am bigger

than the world

it is a brick

within me.

The language is reduced to its beginning, to childhood’s modes of experience in these textual studies of the relationship between body, self, and world. The child and the woman are placed outside the usual metaphors and inside “dark passages / where transformations / vibrate” in the poems’ exploration of how language is born. Such a delicate and elaborate work with language and meaning marks the beginning of a body of work that later unfolds in full-scale novels about childhood and womanhood in post-war Denmark. The movement away from the late-symbolist universe is unmistakable and sudden, and yet there are connections across the generations. The child and art belong together, but in new configurations.

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd