Philosopher and literary critic John Landquist (1881-1974) eloquently described life at Uppsala University in the early 1900s:

“Men and women are ordinarily separated by upbringing, milieu, work, and habits. But we made no such distinctions. We shared intellectual interests, we were students at the same university, we had common friends and instructors (or at least we knew of them), and we were embraced and protected by one city.”

Sweden was the first Nordic country to admit women to its universities. They could receive a degree in Sweden as of 1873, Denmark as of 1875, Norway as of 1884, and Iceland as of 1886. Finnish women, who could obtain an exemption as of 1870, were granted the formal right in 1901. In 1883, Ellen Fries became the first Swedish woman to receive a PhD (in history at Uppsala University). The same distinction was subsequently achieved by Anna Hude in Denmark (1893), Karolina Eskelin in Finland (1895), and Clara Holst in Norway (1903).

Uppsala accepted both sexes with open arms and on the same terms. Was it really that way? Theology student Greta Beckius, to whom Landquist was indirectly alluding, wrote in her diary:

“I can’t help but think about the deplorable situation here, the daily prospect of encountering hundreds of young men, the strain of being the only woman in a circle of thirty or forty friends. My instincts tell me that the mere sight of my bare throat is always on the verge of offending somebody or another. My emotions weigh me down, my cheeks flush, and I’m despondent to the bottom my soul when I ask myself, ‘Why, oh why does it have to be this way?’”

“I’m so very far away from my true happiness, my own self, my goal in life.”

(8 November 1905 entry in Beckius’s diary during her first term at Uppsala University)

Female students ostensibly lived under the same conditions as their male counterparts: they shared ideas, instructors, visions of the future. In reality their situations could not have been more at odds. Men were the beneficiaries of longstanding traditions, the innate right to public support. Like extraterrestrial creatures, women found themselves in an alien world.

A grand total of four women attended Swedish universities in the 1870s. Their numbers gradually increased. Seventeen women were admitted to Uppsala University and twelve to Lund University in the 1880s. The corresponding figures for the 1890s were sixty-six and twenty-eight respectively.

Women asked themselves whether they should try to blend in and focus on what they had in common with men or accentuate their own special qualities. In the 1880s and early 1890s, any term or concept suggesting that they somehow deviated from the norm was scrupulously avoided. Just before the turn of the century, they switched strategy, placing ‘femininity’ in the spotlight and adding the notion of ‘difference’ to their repertoire.

The tide turned in 1896. That was the year Ellen Key published Missbrukad kvinnokraft (Misused Female Power). Demands for emancipation and equal opportunity were supplanted by the concept that women should enrich society and culture with their unique qualities. Love and emotional liberation took centre stage. Women acquired a fresh sense of dignity, as well as new responsibilities, by virtue of their gender.

Thus, two very different generations of female academics shaped the discourse during this period. The generation of Lydia Wahlström, Klara Johanson, and Hilma Borelius started their university studies in the 1880s and early 1890s, whereas the generation of Emilia Fogelklou, Ellen Landquist, and Greta Beckius began around the turn of the century. The first generation were interested in female solidarity and intellectual development. The second generation added the allure of heterosexual bliss.

Woman or Man, It’s All the Same

Lydia Wahlström (1869-1954), who arrived at Uppsala University in 1888, was a pioneer and trailblazer in the generation before Key. She obtained a licentiate’s degree in history and literature; she was the fourth Swedish woman to be awarded a doctorate in history, and she was appointed director of studies at Ahlinska, a private girls’ school in Stockholm, in 1900. She was also a highly productive journalist and author on feminist, scientific, and literary topics.

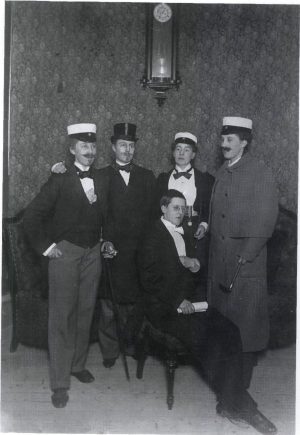

But many people knew her best as the energetic, authoritative founder and chair of the Uppsala Women’s Student Association. Trotsig och försagd (1949; Defiant and Diffident), her suspenseful and deeply rewarding autobiography, describes the situation when the association was born in 1892. The fifteen women at the universities lived at various boarding homes, studied at different departments, and were members of separate student clubs. They had little ability to ‘protect’ each other; the pressure of male students and public opinion was too heavy. Enterprising, dramatic, and confident on the outside, but conflicted and emotionally insecure on the inside, Wahlström became a kind of spiritual guide.

Among those who experienced a lifelong fascination with Wahlström was the gifted critic Klara Johanson, who was admitted to the university in 1894. Johanson, who went by the name of Parveln (little chap) or K. J., was no drab character herself. “The thin little creature with her loosely fitting blue suit, short dark hair, and nonchalant attitude immediately attracted everyone’s attention,” Wahlström writes. It was not long before Johanson claimed sole possession of “the Chairwoman” on the premise that “this big gold nugget cannot be meted out as small change.”

They got into a relationship, which reverberated through the rest of Johanson’s life. Although they had little personal contact after 1898, their connection was a lasting one. After a brief encounter in 1934, Johanson wrote to Wahlström: “During the agreeable coffee and smoking break, your lovely head appeared under the soft lights and my eyes caressed it across all these decades and destinies and people.”

Johanson wrote to Lotten Dahlgren about her tangled relationship with Wahlström, which was on its last legs:

“I have a muddled sense that I had hoped our relationship would recede from the excesses of passion without sacrificing its intimacy. Please try to understand that there was so much beauty and purity and selflessness that, at least for me, it completely shrouded and smoothed over the rest. Save that I had certain ancient Greek viewpoints long before I read Plato. It had a more unfortunate impact on her, given her predisposition for religious contrition and sense of herself as an upstanding member of society. She is never sparing of self-accusation.”

(9 July 1898, unpublished)

Selma Lagerlöf and Sophie Elkan became friends in 1894 as well. Lagerlöf’s letters contain the kinds of about-turns that were typical of the times: from well-meaning advice about a love affair, in this case with the “Belgian”, one minute to furious overtures the next. A letter of April 1894 reflects on the nature of female relationships:

“My feelings for you are not vulgar. I don’t think they ever have been. Suffice it to say that love has not shown its full countenance and that’s why it lets the world continue. It exists for the living more than for the yet unborn. Then who would demand of me that I love one person less than anyone else?”

“That was really an ‘exhibitionistic’ manuscript you sent me the other day. It’s a courageous document. I must confess it rather disconcerted me. It doesn’t lay bare everything, that would be impossible; I could add a little bit here and there. But I won’t.”

(Letter from Johanson to Wahlström on her manuscript about psychoanalysis, 8 May 1945, unpublished)

Thus, 1896 was a landmark year when it came to gender and sexuality. Characteristic of the new trends, which accelerated in the decades that followed, is Wahlström’s 1934 account of why she had started seeing psychoanalyst Ludvig Jekels. One reason was that she wanted to nail down her sexual orientation even though it had not concerned her much before. The “judgment”, as she put it, came rather quickly. She had never been “homosexual but surely bisexual”, which Jekels regarded as the general state of affairs when it came to women.

Johanson put her finger on an important point when contemplating her dalliance with Freud’s theories. A diary entry of 18 May 1936 reads:

“I’m approaching the end of Freud’s twelve-volume Gesammelte Schriften [Collected Writings]. More often than not I think that his arguments sound admirable and correct, but it surprises me that I rarely or never come across anything that has to do with me. He doesn’t know my kind. And that raises serious objection to his theories.”

Johanson’s diary entry of 21 October 1912 makes a prediction:

“Meredith and Raabe – androgynous poets, like Goethe (rather an avatar, I would venture) and perhaps others. In the next century (or the following one or the one after that), unisexual beings will be regarded as incomplete, perhaps interesting specimens instead of the interpreters and arbiters of humanity.”

My kind. The striking thing about sexuality between women in the early 1890s is that fixed categories became unserviceable. To that extent, the period exhibited greater open-mindedness and tolerance than is the case today. Instead of a dichotomy between homosexuality and heterosexuality, there was a sliding scale of emotion – Wahlström’s “woman or man, it’s all the same”, which appeared in her novel Sin fars dotter (1920; Her Father’s Daughter). Male homosexuality was, in Lord Alfred Douglas’s words, “the love that dare not speak its name.” Female sexuality was still not asking the question.

The Swedish translation of Elisabeth Dauthendey’s Das neue Weib und ihre Liebe: Ein Buch für reife Geister (The New Woman and Her Love: A Book for Mature Minds) appeared in 1902 with a foreword by Ellen Key. The book posits female friendship as an alternative to marriage while firmly rejecting lesbian relationships. Nevertheless, it was expected to cause a scandal – discouraging marriage was the “most dangerous thing” Key had ever been involved in. However, Selma Lagerlöf’s apprehensions did not concern marriage. She wrote to Sophie Elkan in April 1902 (unpublished):

“Lindholm had the same idea as I did about what the dangerous book would lead to. Let’s face it: it will become so that two women can’t be friends without people having nasty thoughts.”

Back at the turn of the twentieth century, Wahlström was not concerned about her orientation. Her sexual fervour and impulsiveness bothered her more. The problems are central to her Daniel Malmbrink (1918; Daniel Malmbrink), an erotic novel of ideas in heterosexual guise. But the book does not use camouflage or code like the male homoerotic literature of the day. Wahlström was not interested in the gender of the lovers. Instead, she investigated the nature of love: was it based on fidelity and monogamy, or spontaneity and the ability to fully express oneself?

We Who Are Women Through and Through

What a difference a decade can make. “The thoroughbred woman” was the new motto. A new generation of women had arrived at the universities: 65 (4.1%) at Uppsala and 23 (3.1%) at Lund in 1901-1905.

It was the Sturm und Drang generation. Fulmar, Game Bird, Maiden, and Daughter of a Free Tribe were among the nicknames of the time. Letters were written in a boisterous tone, far from the analytical reasoning and babbling declarations of love that had marked the preceding generation:

“Your letter – you – you see – all I value most, the most precious treasure I know off – everything I reach for and can never attain, but simply to love with my whole being – it is what you possess, what you are. – Such separate paths – such different lives – and – you can never fully understand what you have been and are for me.” Ellen Landquist to Greta Beckius, 23 February 1910.

Emilia Fogelklou (1878-1972), a member of that generation, described it as tragic and shipwrecked. Her verdict was based mostly on three women: Greta Beckius (1886-1912), Ellen Landquist (1883-1916), and Lisa Rolf (1886-1932). Beckius and Rolf arrived at Uppsala in 1905, Landquist in 1906. They studied the history of literature, belonged to the Stockholm student club, and were deeply involved in each other’s lives.

“With a keen sense of purpose, they fought the battle of the new woman in different spheres of life, sexuality included,” Fogelklou wrote. Their education and career were vital: “… they single-mindedly adopted the study habits of men.” With equal intensity, they demanded the inclusion of women’s perspectives in both the academic and sexual realm. “They were saddled with a double burden”, she continued, “and they counterpoised two different types of intellectuality. They all died young and alone.”

For her part, Fogelklou enjoyed a long and productive life: she was the first woman to receive a Bachelor of Theology Degree, was a multifaceted author, and was a hair’s breadth from obtaining a chair in the Psychology of Religion – she was outmanoeuvred at the last minute when the post was redefined. When it came to the others, though, her diagnosis was accurate. Beckius shot herself on 22 January 1912, leaving behind an incomplete erotic manuscript entitled “Marit Grene”. Landquist published Suzanne (1915; Suzanne), the first Swedish novel about a female student. She died of pernicious anaemia the following year. Rolf, the only member of the clique who exhibited any interest in Fogelklou’s philosophical reflections, became the Lund city librarian in 1927 and died in 1932.

Among the strange and fascinating titbits about the threesome was that the two male characters in Beckius’s manuscript were based on Landquist’s and Rolf’s brothers John and Bruno. There were other curious confluences as well. Both Beckius and Dahl recounted the empathetic and erotic sensibility of the Bruno character (they had visited him at the same time in Stockholm). During the final phase of his relationship with Beckius, John Landquist had a liaison with Maria von Platen, who was to have a far-reaching impact on the depiction of women in Hjalmar Söderberg’s novels, and who introduced him to Elin Wägner. He and Wägner later served as literary advisers to Ellen Landquist when she was writing her novel, which was partly based on Beckius’s life.

This generation of women was more determined than ever before to make their voices heard. Landquist wrote to Beckius about her participation in the licentiate seminars in the history of literature:

“Remember that you are the first one up there, fully conscious, while they walk around as blind as ever, oblivious to the fact that a young woman is casting bullets capable of piercing their proud edifice. Think of yourself as an envoy with a thousand supporters cheering you on.”

A rough draft that Beckius wrote around 1911 about literary history laments:

“After I had proceeded from the [analysis] to work my way through the rigid systematisation, the schematic dissection of how ideas and poetic forms have evolved, the long abstract lines along which individuals are placed almost in numerical order, I stood there empty-handed before those very individuals with just as many questions. My enthusiasm for the wide panorama subsided, and I began to look more closely at where the analysis fell short – the spontaneous creativity of human beings.”

A woman is an autonomous being, “a lucid female spirit”, equal to but independent of men. Ellen Landquist in a letter to Greta Beckius: “How many people know of or even suspect the existence of that which we call a woman, a being, spiritual, living for herself, conscious, apart from men, free, glorious, gazing at the mountaintops.”

Suzanne is a finely tuned study of female sexuality, spirituality, and emotion, a forerunner of Agnes von Krusenstjerna and the “truth about women” that she sought to convey in her books. Beckius’s “Marit Grene” is a denunciation of the heterosexual culture that is so deadly for women.

To all appearances strong-willed and efficient, she was the leader of the threesome. Each of them regarded herself as Key’s follower. “I read her the way a hungry person consumes something she has longed for all her life”, Beckius writes in “Marit Grene”.

“I have often thought about the fact that people blame Key for ‘wasted lives’, ‘moral dissolution’, and the like”, Beckius writes in “Marit Grene”. “That’s so absurdly superficial. She never encouraged lust. That has always been around. But her words fell like a fresh spring rain and caused a seed to sprout in all of us, because it aroused the longing for light and exaltation, admittedly undefined; but we felt that we had to find it, each of us in her own way.”

The Uppsala University students were not the only captives of sexual delirium. Signs were popping up everywhere that both the older and younger generation had resolved to redefine and gain control over their sex lives. As Landquist’s letters to Beckius in 1910 make eminently clear, however, widespread confusion reigned.

“Have you read George Egerton’s Keynotes? A marvellous book by a woman. But when I read it, I felt as though all these thousands of notes lacked a final chord.

And that’s the way it is with many women. With Marika Stiernstedt’s Gena, Söderberg’s Gertrud, with Nora, who went out to find her final chord – but did she find it? – Ibsen doesn’t have a clue.”

“Strödda blad” (Scattered Pages) by Beckius, around 1911.

On the one hand, men were not up to the challenge posed by the new woman: “What man has it in him to satisfy our demands, Greta?” On the other hand, they were ineluctably superior: “Do they have any idea how prodigious they are?” The ultimate goal was love. But women also felt a need to steer clear of it. Landquist writes: “I don’t want to put my foot there. I want to be free and natural and alone.”

Hildur Sandberg (1881-1904), a student at Lund University, led a kind of parallel existence to Beckius. She entered the medical curriculum in 1900. Somewhat older than Key, she could look back at an earlier life. A letter that she wrote to Key describes the time when she was a “feminist in the narrow sense that so many people swear allegiance to – the credo that women should be like men in all respects.” Reading Key had given her deeper insight:

“It goes without saying that I haven’t abandoned all those ideas about women’s emancipation, but the very concept has grown; if true love ever comes my way, I will obey its command – I think it would be a terrible crime not to do so.”

And she was true to her word. During the 1904 Christmas holiday, a year before Beckius was admitted to Uppsala University, she was found unconscious outside her lover’s room. She died a few hours later. While the symptoms suggested she had been poisoned, no direct evidence was ever obtained. The incident attracted a great deal of attention and appears in one form or another in a number of novels and biographies. Among the legends are that rumours around town drove her to suicide and that her lover wanted her out of the way. Arnold Norlind (1883-1929), Fogelklou’s future husband, adopted a melodramatic tone when writing about Sandberg and her lover:

“She was like a zombie for the last few weeks. You could see the blood draining out of her day by day – she had obviously fallen into the clutches of a vampire. I have never seen such a sleepwalker in all my life; there was an eerie light in her eyes. She was a completely different person, had lost her old self – she not only resembled, she was a sleepwalker. Her soul had died.”

Marit and Suzanne

The concept ‘soul-murder’ (själsmord; close to suicide – självmord) hovers eternally above Sandberg’s name. It is the main theme of both “Marit Grene” and Suzanne. The crimes of men are at centre stage: “Marit Grene” makes it clear that their manifest offences have already been discounted: “That men seduce, abandon, and violate women is nothing new to us.” The real crimes are the involuntary, unconscious acts: “soul-murders” – products of men’s unquestioned right to define the parameters of reality.

In ways that foreshadow Luce Irigaray of the late twentieth century, both works argue that there is only one sex – men. Women succumb because their voices are stifled. “Marit Grene” again: “He doesn’t take the time to listen to the secret pulse of her soul – his ear is accustomed to more sonorous tones than those miserable tremors.” The purpose of Beckius’s manuscript is to lend suicide a female voice:

The ‘unisexual’ nature of contemporary culture is a central concept in the thinking of French philosopher and psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray. Women find themselves in ‘exile’, divorced from their gender and sexuality. Ce sexe qui n’en est pas un (1977; The Sex Which Is Not One)argues:

“The dominion of the phallus, its logic and system of representation, are just so many ways of separating women from their sexuality and depriving them of their self-esteem.”

“And women dare not speak of their secret lives because shame suffocates them. But it must be spoken.”

The theme of both stories is a woman’s ‘exile’. “Marit Grene” links it to sexuality with extraordinary naturalism. The first love story, based on Beckius’s relationship with John Landquist, represents a kind of ‘banishment’. “Marit Grene” and Beckius’s student diaries paint a similar picture. Male sexual behaviour is a force field, a territory, that draws women into it. Men’s onslaughts plunge her soul into “a listless torpor”; she grows sluggish and vacuous, divorced from herself. “For I died under his hands” (“Marit Grene”). Her own desires and preferences go unheard. “What I wanted and thought echoed nowhere in his consciousness.

“I lay in his arms, in his bed. My lips didn’t want to kiss him, sought to avoid him at all costs. Shaken by convulsions, he commanded me fiercely, ‘Kiss me, kiss me.’ I turned my face and kissed him mechanically, coldly, and lifelessly. He had such a strange way of kissing. He made me all grimy and tried to pry open my mouth with his tongue. What good was that? I found it frightful and repugnant, and I always washed my mouth out afterwards with cold water, though I never thought it helped very much. But I didn’t want to hurt him, so I didn’t say anything. Certainly he knew better than I did, I thought despondently.”

“Certainly, he knew better”! Men hold the sovereign right to define every aspect of reality, including women’s sexuality. “Of course we have natural instincts; they speed from heaven to earth to hell and back again. And it’s all in men’s power.”

Heaven is conspicuously absent in “Marit Greene”. But the work’s second love story, which is based on Beckius’s relationship with Bruno Rolf, suggests a way out of the impasse. As a new man, he represents the promise of a different kind of sexuality. “Marit Grene” ends with a meticulously crafted sex scene, a kind of initiation rite. It is as though the manuscript is proposing a mutual erotic baptism that abolishes the male monopoly.

In one of the passages before they have sex, the man combs Marit’s hair. His soft touch is like a missive from her own desire.“He knew how to caress Marit like she wanted to be caressed – like that – so lightly – so gently – no other way.” He lies down next to her and is still, responsive. It’s as though he’s being guided, but not by her: “By something higher than her. Far above both of them. And the Higher Power had found such a secure abode in him that he could lie beside Marit without trembling.”

The manuscript was never published. Beckius wrote it while spending a lonely winter in a Dalecarlian cabin recovering from a nervous breakdown. Her father had suffered a stroke and she had broken off her studies. The next crisis arrived in January. A friend from Uppsala came and brought her back. Shortly thereafter, she shot herself in the other woman’s house. She left all her papers, including the largely completed manuscript, to Fogelklou. However, her younger sister destroyed most of it sometime in the 1960s.

“It came to a tragic end. She couldn’t go any farther. Assuming that nobody would grasp the urgency of her message, she didn’t think it was right to accept either hospitality or financial assistance. That was before the age of modern psychology, when people began to speak as openly as she had about such questions. She had an inner need to understand sexual yearnings from God’s point of view. Such a struggle for expression, not only freedom of behaviour, may seem ludicrous and impractical – and to some extent it was. But it is typical of a certain stage of women’s liberation, ‘full of intellectuality and gravity, torn asunder by consciousness.’”

(Fragment from an unpublished manuscript around 1956 – Fogelklou writing about Beckius)

Suzanne describes the near-downfall of the protagonist, who resembled both Beckius and Landquist in a number of ways, due to the sexual milieu in which she finds herself. Her case was also to be reminiscent of Sandberg. A rumour sets the destructive chain of events in motion. Her first defeat is due to the distrust she awakens as a student and friend. The man she loves falls prey to the slander and abandons her.

The inner logic of Suzanne, the inevitable disgrace of women as sexual creatures, is skilfully developed. As is the case with “Marit Grene”, Suzanne is drawn into a force field, an alien territory. Norrestad, her grandfather’s farm, symbolises the homeland she has lost. Her father has sold the farm. “When that happened, it felt as though I had been yanked out of the soil, roots and all.” She dreams of recovering and cultivating it.

The alien territory draws her farther and farther in. After her lover leaves her, she is raped by a friend, the counsellor at the student club. Her pain has no outlet; women’s voices fall on deaf ears. A stark image of her plight appears early in the book when she is sitting alone on Slottsbacken in Uppsala as the sun rises. She starts to tremble, a shriek rises from her throat, “and nobody heard the low, broken cry that emanated from deep, primordial agony.”

All of her experience is denied and repressed: “It’s not supposed to exist.” Her sense of self, her connection with her own will, gradually diminishes. Like Marit, and Beckius, she is seized by feebleness and lethargy.

An appointment with a neurologist serves as a kind of climax. The episode is one of the first Scandinavian descriptions of psychoanalytic methods, a parallel to Freud’s case history of Dora. The encounter this time, however, is seen from the point of view of the young woman, or victim: “Between these four green walls was a brain that worked systematically, synthesised indifferently, and made her its object.” Suzanne pronounces a harsh decree: “A man must not and can not pass judgement on a woman when she is going through one of the crises that turn her life upside down, for the simple reason that he is unable to dispel his own preconceptions about us.”

The neurologist’s officially sanctioned terrorism is the most profound insult that Suzanne is forced to endure. His civilised abuse gives birth to violent fantasies of revenge:

“She clenched her fists in a wild, delirious desire to seize him by the throat – to spring on him like a panther from behind, to hold him beneath her and squeeze him right there, harder, harder – to hear his desperate gasps.”

Her last great disappointment is sleeping with an older poet. The lifeless face exposes the emptiness of what he has to offer. If that is all there is, she would prefer to let go of it:

“I know full well that I’m a sensualist. Name a woman who isn’t. But haven’t we been given as much strength to live without it, knowing that such experiences will make us neither proud nor happy, as to live with it?”

As opposed to Beckius, Suzanne actually survives. In the final scene, she throws away the revolver that she had held to her temple so many times.

But that isn’t the end – the web of fact and fiction becomes even more tangled when Wägner picks up where Ellen Landquist left off in her novel Den namnlösa (1922; The Anonymous Woman). With Landquist as a source of inspiration, the book chronicles the deadly gender relations of modern society and the prospects for another state of affairs.

Klara Johanson

Klara Johanson (1875-1948) was the genius among the first generation of women at Uppsala University, Emilia Fogelklou among the second. Both tread the stony path of pioneers. Whereas Johanson was a critic and essayist, Emilia Fogelklou pursued a career as a theologian and scholar. From the very beginning, both of them adopted a feminist and gender perspective as a matter of course. Johanson wrote to Ellen Kleman in 1913: “Unknown women geniuses – the past is teeming with them when you begin to poke around in it. You can tell which sex has written history, but we still don’t know which one actually made it when all is said and done.”

Johanson received a B.A. from Uppsala University after having studied the Nordic languages, Latin, Greek, aesthetics, and philosophy. She had grown up in a middle-class but “uncommonly bookless” home, the youngest child of a cap maker in Halmstad. Her father’s suicide when she was fourteen added a peculiar dimension, nebulous and luminescent, to the rest of her life. She looked at it as both a wound and a distinction, constantly leaving her on the edge of the abyss.

After a meteoric career as a critic, she retired almost completely from the public arena in 1910. She had a lifelong need to be anonymous and play the role of the outsider; self-contempt and melancholy pursued her wherever she went. Her psychological make-up seems to have been based on swings between low self-esteem and delusions of grandeur.

An Aesthete Pure and Simple?

Johanson is often portrayed as an aesthete pure and simple. But art was not her primary concern. The titles of her books of literary essays, Det speglade livet (1926; The Mirrored Life) and Det rika stärbhuset (1946; The Rich Inherited Estate), suggest that art is the reflection and heir of life respectively. Art mimics life in the same way that a critic mimics art.

Johanson’s aesthetic searched for the human idiom. But the emphasis on expression can be misleading. Her inquiry focused on the extent to which language communicates with the inner voice. From that point of view, she was in the tradition of Fredrika Bremer, Karin Boye, and Hélène Cixous. What interested her was the present voice, the words that point back to experience and transmit acquired wisdom. “Whence comes the authority to think and write? The voice, I have always said, the voice. That’s where you’ll find the signed power of attorney.”

Johanson’s career is typically broken down into three phases: critic and journalist for Dagny/Hertha and Stockholms Dagblad (1898-1914); philological research in connection with publication of Fredrika Bremer’s letters (1915-1920); and essays and other writing in Tidevarvet and other periodicals (1920-1948).

Johanson had another feather in her cap. She translated Knut Hamsun’s Victoria (1898; Eng. tr. Victoria), Clara Viebig’s Das tägliche Brot (1903; Eng. tr. Our Daily Bread), Henri Frédéric Amiel’s Fragments d’un journal intime (1883; Eng. tr. Amiel’s Journal: The Journal Intime of Henri-Frederic Amiel), Benedetto Croce’s Brevario di estetica (1913; Eng. tr. The Breviary of Aesthetic), and other works. While at the university and during her early journalism career, she also wrote farces and published poetry and short stories in periodicals.

What she called her “unproductive periods” presumably referred to her lack of literary output.

During the third period, she published four books of her own: the two books of essays mentioned above, a collection of aphorisms entitled En recensents baktankar (1928; The Ulterior Motives of a Reviewer),and the polemic Sigrid Fridman och andra konstnärer (1948; Sigrid Fridman and Other Artists). During her “unproductive” years, she wrote letters (a selection of which was brought out in 1953) and kept a diary (extracts published in 1989).

In addition to her criticism and essays, she published collections of satirical and lyrical prose under the pseudonym of Huck Leber: Oskuld och arsenik (1901; Innocence and Arsenic) and Ligapojken Eros (1907; Eros the Hooligan). During her years with Tidevarvet, she pursued the tradition in what she called Observations. The radical feminist milieu at the magazine inspired her to write a couple of classic columns when it comes to sexual politics: “Sexualsystemet” (1924; The Sexual System) and “Den inre rösträtten” (1924; The Inner Suffrage).

Her “innate” sense of style was both a gift and a curse. Her eagle eye detected every little flaw, particularly in her own writing.

Her pseudonym was an homage to Mark Twain and his Huckleberry Finn. At the core of her style is humour, a style which presupposes a certain consensus of values or mutual understanding.

Paradoxically enough, given her identity as an outsider, the particular strength of her style is the ability to create whatever consensus is required. Two of her early journalistic masterpieces lampooned phenomena of the age: fin de siècle flâneur literature and Ellen Key’s ideal of harmony. She pulled no punches when discussing Sigfrid Siwertz’s first book of poetry: “Isn’t it strange that all these young poets of ours seem to have the same lady friends, prowl the same streets […] dream their lives away on the same melancholy beaches, and sniff the same flowers? Out-and-out communism is what I call it.”

Talking about and describing humour is always tricky. What makes Johanson’s style so witty? Much of it has to do with the sense of intimacy she evokes: subtle allusions, restatements of proverbs – “never a day without disillusion” (nulla dies sine linea) in reflecting on Malla Silfverstolpe, the salon hostess who was eternally writing her memoirs. Another device, based on the same proximity to her readers, is to transmute lofty and grandiose ideas into ordinary and familiar concepts.

Johanson’s style flourishes best in the soil of intimacy and admiration, as in her reviews of Selma Lagerlöf or her essays on Fredrika Bremer, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Søren Kierkegaard. Her first book of essays begins with several about Goethe, while Kierkegaard is the topic of the last few in her second collection. Bremer staked claim to nearly the entire middle phase of her career. Publication of Bremer’s letters, sometimes considered one of the most important events in the history of Swedish literature, provided her with an excuse to indulge in what she called her “philological inclinations” – the legacy of her student days and acquaintanceship with linguist Adolf Noreen.

Her relationship with Sigfrid Fridman, a sculptress (the “Stonecutter”) during the last twenty-five years of her life was important to her career. Once again, Johanson – the “ruffian” or “younger brother” – was the one to draw the sword. The public debate about Fridman’s art smouldered for several years, flaring up on a couple of different occasions. Johanson stood intrepidly in the line of fire. The first round concerned the sculpture of Fredrika Bremer that is now in Stockholm’s Humlegården Park. The second time was about “Kentauren” (The Centaur), which stood atop Observatory Hill until it was recently vandalised. After being restored, it once more stretches towards the Stockholm sky.

“Alwilda von Glückentreff: Connoisseur of the Art of Living” was the title of her Ellen Key parody. The style imitates Key’s exuberant hyperbole. Johanson captures her entire gospel in one fell swoop: her pantheistic world-view, far-reaching individualism, sex as religion, zeal for educational reform, gender dichotomy, the aestheticisation of everyday life.

The column ends with Alwilda seated at her tea table. Her home adheres strictly to Key’s ideal of harmony: no shadow of malapropos ‘masculinity’ or ‘abuse’ of female power falls over her. Encircled by “the monochrome wallpaper without which newly emancipated individualism is seized by blasphemous desires”, she rejoices “in the degrees she never received, the places she never set foot in. She is the supreme paradigm for the woman of the future, whose dream is to wean herself from the dictates of utility and chisel her life into a work of art.”

Ecclesiastical and conservative voices howled in protest when Key was honoured on her sixtieth birthday. Johanson came under fire once again; she and Key were accused of dragging young people into the “swamp of lechery”. Exhilarated as usual by the opportunity for polemics, Johanson wrote to Lotten Dahlgren:

“While Key and I argue about what road to take,

we end up burning at the same stake.”

(29 December 1909)

Friends and Patronesses

Female solidarity is the ultimate source of Johanson’s inspiration, so solitary and vulnerable at the same time. First the Uppsala clique, then the Nya Idun (New Idun)women’s association, then the magazines, Dagny and Tidevarvet. Her friends and patronesses were indispensable: She was “Parveln” (Little Chap) to the “Chairwoman” (Lydia Wahlström) and “Lille Eyolf” (Little Eyolf) to the “Editor” (Lotten Dahlgren). In 1912 she was dubbed the “Chosen Ruffian” for all time. That was when she began living with Ellen Kleman, the editor of Hertha.

Another paradoxical feature of Johanson’s life was the extent to which, in her own words, she served as “a trusty little help agency and not only for literary supplicants” despite her childish image – a permanent literary adviser, as well as a counsellor and emotional pillar of support. Her apolitical manner notwithstanding, her letters and diaries meticulously chronicled and commented on current events, particularly during the Nazi period. She was also the first Swede to write about the German expressionists and associate them with the experience of having fought on the front lines in World War I.

“Søren och jag” (Søren and I) was the working title of a book she planned to write about Kierkegaard. She shared his shyness, alienation, passion, commitment, and proclivity for pseudonyms, not to mention the tragic “secret”, the melancholy that stemmed from her father’s death and informed a lifelong mission. Nevertheless, female esprit de corps furnished her both a counterweight and a safety net.

She was propelled not only by vulnerability, but by the “dynamic force” of love that she found in Bremer. She wrote to Margit Abenius, the author of the first major essay about her: “You have read my work as if it were a love letter, and for the most part that’s exactly what it is.”

Translated by Ken Schubert