The eighteenth-century diary does not have the private or outright secret quality that it acquires in the course of the nineteenth century, when it is often written as a journal intime as the writers become more analytical and self-scrutinising. Eighteenth-century diaries, like the letters, were written with one or more readers in mind – be they children, family, or future generations. These readers were sometimes addressed directly in the text.

Women’s diaries that have survived in Swedish archives can be divided into four different types: Metta Lillie’s diary, written between 1737 and 1750, could be characterised as a form of family chronicle; Christina Charlotte Hiärne’s diary, written from 1744 to 1804, is dominated by religious thoughts; akin to both these types, in form as well as in content, is the diary kept by Märta Helena Reenstierna, known as Årstafrun (the Årsta lady), in which she recorded details of daily life at Årsta Manor just south of Stockholm between 1793 and 1839; the third type of diary is that of Duchess, later Queen, Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta, written from 1775 to 1817, which is all but a court chronicle. These women moved in the most influential circles: the aristocracy, people of the official class, and the royal family; with the exception of colonel’s daughter Metta Lillie, who lived on an estate in Västergötland, they all lived in or near Stockholm.

In 1782 Friederike Brun published her first book in Denmark, Tagebuch meiner ersten Reise (Diary of my First Journey). Although travel diaries were being written in Sweden in the late eighteenth century, as a fourth category of diary they had yet to go beyond the stage of dilettantism – despite the fact that the genre was already so common in Europe that it was the object of parody.

Metta Lillie (1709-1788) begins her diary in 1737 as a family chronicle. She records her parents’ 1706 marriage and lists the births of her eight siblings.

“In 1709 I was born, who is called Metta Magdalena Lillie […]. A tutor who gave lessons to my dear brother taught me to read Swedish, and another tutor, called Hälstadius, taught me to write. In 1722 a Danish lieutenant, called Morlan, came and taught my sister Hädvig and me French. In 1714 my parents moved to the lieutenant colonel residence Örby, where we were for ten years […]. All that carefree time and most of our childhood we passed at Örby, my sister Hädvig and I.”

She then notes important events in her father’s family – births, weddings, deaths – and, once that has been taken care of, she sets to work on her mother’s family. Abruptly, however, current reality interrupts the family chronicle. In 1738 Metta Lillie’s father dies: “the nineteenth of October in the morning it pleased Almighty God to make us unhappy beyond all measure and call our noble and loyal father away from this world.” This critical event in the life of the family has a direct effect on her writing. The text, which has so far been guided by a margin, now flows over the entire page, thus manifesting the strength of her emotions.

When in a good mood, her father, a military man, had been happy to talk about his exploits, and Metta Lillie writes proudly that “he was indeed a valiant officer”.

Times now become hard for the family; the mother has four unmarried daughters to provide for, the only son gets a job in Stockholm. At this point the diary proper begins: a chronologically dated record of the Lillie family’s life at the Hjertered estate in Västergötland.

Family affairs are still important; Metta Lillie is constantly noting down all significant events in her wide circle of aunts, cousins, et cetera. Alongside this principal theme of family, however, the diary deals with other topics: finances, politics, religion – and also Metta Lillie’s personal destiny.

One of her sisters gets married and Metta Lillie describes the wedding preparations. The detailed specificity of her descriptions brings to mind the travel reports written by her contemporary Carl von Linné [also known as Carl Linnaeus or Carolus Linnaeus], and they become a form of ‘poetry of reportage’:“On January 18th, Bengt i Hafvegiärde came home with 3 loads from Gothenburg, where he had bought wine, confectionary and groceries for 140 daler [rix-dollar] in silver coin. The confectionary cost 40 daler in silver coin. The wine was a half cask [approx. 20 litres] French, a half cask Pontac, 4 pitchers hock, 4 pitchers Portuguese, 2 pitchers French spirits, tea, coffee beans, chocolate, oil, vinegar, capers, some oysters, lobster and other things not necessary to name. Baron Fleetwood [the bridegroom] sent a half barrel of oysters to here, a half barrel lobster and a roe deer.

“On February 3rd, in the blessed name of God, they were married by my dear mother’s family pastor Mr. Ekberg. May Jesus Christ be their protector in all their days and grant them his charitable blessing for ever and ever.”

The years pass and Metta Lillie notices that people’s attitude to her changes once she has passed the age of thirty. Why is she treated unkindly? She is the same person, after all, she performs her tasks in the home, and takes part in wedding and funeral preparations along with the other womenfolk in the family. She studies the Bible to find an answer to her anxious questions; she feels old and begins to suffer from poor eyesight. In 1744, at the age of thirty-five, she exclaims:

“Merciful God, what in your wisdom and your solicitude have you resolved for me and my three sisters, you whom it has pleased that we should enter this world?”

The teachings of Protestantism made the woman’s duty very clear: wife and mother, support for her husband and child rearer. The unmarried woman – of whom there were many during the Age of Liberty, several generations of young men having been decimated by war – had no specified purpose.

The Age of Liberty is the name given to the half century of Swedish history from the death of Karl XII in 1718 to Gustaf III’s coup d’état in 1772. The name is a reference to the fall of absolute monarchy and is suggestive of the freer system of government operating during the period.

The Lutheran Table of Duties, a detailed specification of duties pertinent to the various stations in family and society, assigned her neither role nor function. In reality, of course, she often played an important role helping her married sisters and her siblings’ children.

The Table of Duties, part of Luther’s Small Catechism (Der Kleine Katechismus, translated into Swedish c. 1544), summarises the ideology of the Old Lutheran community. It fell into three categories: Church, society, and home – or teachers, public authorities, and household/family. The norms of behaviour listed in the Table of Duties were the mainstay of thought and action, inculcated in the congregation through reading the Catechism and listening to sermons. Children ought to learn them by heart, wrote a pastor in the 1770s. Under the heading “For Wives” we read:

“Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as unto the Lord, even as Sarah obeyed Abraham, calling him lord; whose daughters ye are, as long as ye do well, and are not afraid with any amazement.”

Metta Lillie’s growing bitterness concerning her lot in life ceases when a suitor appears on the scene, a widower with six adolescent children. With apprehension and trembling, and after a brief period of reflection, the now forty-one-year-old Metta Lillie accepts his proposal: “It is my greatest comfort that I have followed my mother’s will in this matter.” The account of her wedding is brief. On February 21 1750:

“[…] my wedding took place in the Holy Name of the Lord Jesus. That day, in my great weakness, I wished […] that my my my Jesus should be there at my wedding. Kind, mighty Jesus, never relinquish me from your blessed Providence.”

“On February 27th 1750 I moved with my dear husband from my gracious and good mother and my dear sisters. That day was a sorrowful and heart-wrenching day, Jesus helped me. My dearest sister Hädvig was allowed to come with me, my dear brother and good sister-in-law likewise departed from my mother that same day. We went together as far as the tree, whence my dear husband, my sister Hädvig and I travelled to Lundby.”

A new life now begins for Metta Lillie: wife and stepmother to six children. And at this juncture, just when she is about to face up to the greatest challenge of her life, her words abandon us. The diary ends. The reader is left with many unanswered questions: What happened next? Was she happy? What kind of a relationship did she have with her husband? Did his children accept her? Why did she stop writing at this particular juncture?

One characteristic of the diaries is their close link with the life of the writer. That the words dry up does not necessarily mean Metta Lillie was unhappy; she might have been so busy with her new life that she no longer had the time to write. It is not unusual for women’s diaries to come to a full stop upon marriage.

Metta Lillie’s diary is a fascinating document: an early example of a Nordic woman’s personal records. It is a clear indication that the diary has its roots in family records and in household economy. It also suggests another source of diary writing, in thoughts about religion and in concomitant existential questions: ‘What has Your purpose been with my life, God?’ The diary often breaks into long interspersed prayers or conversations addressed directly to God and to Jesus. In 1741, for example, Metta Lillie writes:

“[…] kindest Jesus, remember that you yourself took our father away and promised to be father to all the fatherless. Guide us and lead us according to your merciful will.”

Following the death of her father, the daughter-role in which she had cast herself, and in which she had understood herself in relation to her father, is transferred onto Jesus. She presents herself as weak and frail, as someone needing support. It could be that some of the anguish she feels over the issue of marriage is caused by the new and radically different demands now being made of her: to make decisions and be personally effective.

Even in this early example of a diary, it is already evident that the very act of writing liberates thoughts and feelings. What begins as an impersonal family chronicle is cut short once Metta Lillie has taken shape before our eyes as an intelligent and sensitive individual with a growing ability to express her attitude towards life.

For Metta Lillie, estate and family are key concepts. The estate is the place that gives life its rhythm of work and rest, everyday and feastday, and the family is the supra-individual context that gives a meaning to her life.

For Christina Hiärne (1722-1804), the twentieth child of Professor Olof Rudbeck the Younger in Uppsala, life follows a similar but also different pattern. Family and estate are important to her, too, but the paramount context to which she conforms is that of religion. She and her husband belong to the pietistic revivalist movement that arrived in the Nordic region during the eighteenth century and led to the establishing of communities in various locations, including Stockholm. In the 1750s the Hiärne family went over to Herrnhutism.

Christina Hiärne kept a diary for a large part of her life. She began writing in 1744, aged twenty-two, and wrote up until a few days before her death in 1804. The diaries, which remain unpublished, are written in six small attractive rose-pink, light-blue, and yellow bindings. They largely deal with her religious life; church services, the Eucharist, conversations with the pastor, doubt and soul-searching, everything gets written down. But this diary is also full of practical notes on slaughtering and baking, illness and visits, and on cultivation of the land at the family estate in Brunna outside Uppsala. As was the case for Metta Lillie, a lot of time is spent in the company of kin and friends. A whole day without a visit is so unusual that it will be mentioned in the diary.

The daily entries are often short and to the point, but when something important happens this pattern is broken – as is particularly evident when her only son is born. Brief lines are here replaced by a long narrative full of emotions and details: “[…] on 17 February according to the old calendar 1747 I got up and felt well. My cousin was sewing at the sewing frame. At ten o’clock my waters broke rapidly, the baby had not yet turned, nor had I had any contractions. I became ill at ease and did not know what it meant but sent for the woman from the village to find out, and then straight away sent for the midwife in Uppsala […]. The birth was hard, and the midwife asked those present to pray to God and she was perplexed. But the Lord had heard my prayer and calmed my heart, although my body endured terrible pain, and granted me patience. My dear husband was attentive the entire time and most concerned, and therefore I forced myself to the very greatest extent not to let him see how much it was hurting me, so as not to make him fearful. Eventually, nearly all thought vanished from my mind, and at half past six the Lord helped me give birth to my firstborn son Urban Olof Hiärne. May the Almighty let him grow up to his Creator’s honour and be given life in Jesus Christ for growth and blessedness. He was born folded double with backside first, head, arms and feet followed, and then my cousin Stina Regina said: O my soul, Bless the Lord.”

This son was later to cause his parents many worries, and the subsequent years of her diary are filled with prayers and questions about his character and fate – addressed to God.

In May 1765, Christina Hiärne writes, with metaphors taken from the Bible:

“The maternal heart fled like a hunted deer to my dearest compassionate and steadfast Saviour’s bosom […]. I shed many sighs and tears at His feet on account of this prodigal son, our only child, and discussed it all with my Lord and said to Him that I understood that He would humble me very deeply with all this.”

The reader gets the impression that this diary, like Metta Lillie’s, relates very closely to ongoing events. But from certain references that point into the future, we gradually realise that Christina Hiärne made fair copies of the diaries in her old age, and took the opportunity to ‘edit’ them. In so doing, she has given the text a structure that would be impossible in an ‘unedited’ diary. One of the highlighted themes is how she and her husband were made for one another; another is her spiritual disquiet and restlessness before her pietist awakening.

Christina Hiärne also finds the actual act of writing her diary to be a satisfying occupation in itself; she can write about her sorrows and seek comfort for anxiety about her son: “I have heard your prayer and seen your tears. The Lord Jesus says these fair words of comfort to my soul. This morning, the Lord gave me a lovely solitude and tranquility so that I could write what befell me yesterday, and how I felt about it. Today, though, I was somewhat gloomy […].”

In 1793, Märta Helena Reenstierna (1753-1841) embarked on a lengthy project: for forty-seven years she wrote a detailed diary describing work and celebrations great and small on the Årsta estate south of Stockholm. A selection from her diary, known as Årstadagboken (The Årsta Diary), has been published in three illustrated volumes (1946-1953); it is an important historical document with regard to daily life around the turn of the century.

Märta Helena Reenstierna had married Cavalry Captain Christian Henrik von Schnell in 1775. Their friends included Carl Michael Bellman. As the estate was close to Stockholm, there was a ready market for its produce. Among other goods, Märta Helena Reenstierna sold attractive decorative butter pats for parties held in the capital. She had eight children, seven of whom died as infants. Judging from the dates of their deaths, it would seem that several of them died during an epidemic. In 1793, when she started keeping a diary, she was forty years old, and her surviving son was an adolescent.

The language in the diary is that of concise, straight-forward observation. She is interested in events and occupations; analyses of thoughts and feelings appear but rarely. On the other hand, Märta Helena Reenstierna has a sense for the dramatic situation and remark, and she paints a vivid picture of life at the time. A day in 1797 is summarised as follows:

“22 Friday. Some frost and then a little fine snow. Half past 5 in the morning I began preparing the dough for 2 rye loaves, 2 malt loaves, 2 wheat- and 2 pastry doughs. My 2 servant girls Christina and Catharina assisted with kneading the whole-grain dough and putting the dough aside, while I did nearly every single thing, worked the dough, formed saffron bread, pastries and almond biscuits, then pricked the dough, attended the baking itself in the bakery, and finally I counted up all on my own and carried it all in, 228 small cakes and biscuits, and 52 large cakes.”

“March 1820 1st Wednesday. I received a letter from my sister, and Inspector Bergman had sent me Mrs Lenngren’s splendid verses [these being Skaldeförsök (Poetic Attempts) by Anna Maria Lenngren, published by her husband, 1819]. 2nd Thursday. Beautiful, fine weather. Mrs Lenngren’s book amused me greatly today.”

Between 1775 and 1817, Duchess Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta (1759-1818) wrote a voluminous diary of more than 4600 printed pages. She had come to Sweden in 1774, a fifteen-year-old German princess, to marry King Gustaf III’s brother, Karl; the following year she started keeping a diary. The marriage was unhappy. Duke Karl was renowned for his sexual escapades with ladies-in-waiting and actresses, activities which he suspended for only a brief period after his marriage. Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta bore him two children, in 1797 and 1798 respectively, but neither survived. Her hopes of finally becoming a mother, and thereby having a meaningful existence, were thus crushed. In 1809, she became Queen of Sweden when her husband ascended the throne as Karl XIII.

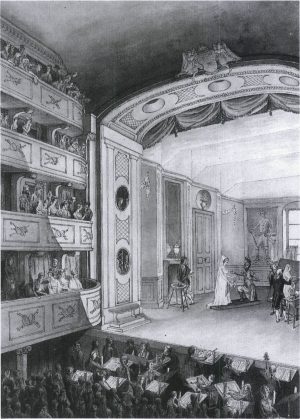

Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta’s diary is one of the most important historical documents relating to the Gustavian and post-Gustavian era. It was written in French, and drawn up as monthly letters summarising the most significant events at court during the preceding month. Having initially favoured descriptions of court parties and entertainments, which to a large extent consisted of theatre performances arranged by Gustaf III, as she grew older Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta became increasingly interested in political issues.

“My face is not that of a beauty, on the contrary I myself have difficulty tolerating it, and personally think […] that I have a highly impertinent appearance, which […] would mostly seem to invite a box on the ears […]. I detest flattery, but welcome praise where praise is due, and I like to please, although more by the qualities of my heart that by my appearance.”

Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta Dagbok I (Diary, vol. 1)

In order to fill the lonely vacuum and “to have an ongoing occupation, both worthy of me and at the same time agreeable, for my active mind, I decided to write down everything that occurred before my eyes.” However, she writes in a preface, it would be far too dull to write only for herself: she needed someone to write to, someone to write for. The entries in the diary are addressed to a woman of her own age, her best friend since her arrival in Sweden: Sophie von Fersen, who became Sophie Piper upon her marriage in 1778. Like Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta, Sophie Piper was trapped in a marriage of convenience. Sophie Piper is the diary’s ideal reader, the one being spoken to: “You desire of me, my dear friend, a meticulous account concerning everything that occurs here.”

The diary also, however, addresses itself to posterity, and gradually assumes the character of court chronicle and political document.

Over the years, Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta also wrote thousands of letters to Sophie Piper, alongside the diary – affectionate, tyrannical, romantic letters, full of the Pre-Romantic nurturing of friendship. And it is quite obvious that friendship and dialogue with Sophie are the motive powers in her extensive writing project. These discourses keep her pen writing and her heart beating, even when the two friends are apart.

Time and again she returns, in reality and in her thoughts, to the bosquet délicieux, the delightful bower in the park of Rosersberg Palace, where she and Sophie sat in affectionate conversation. She later sits there alone, reading and dreaming. And from here she writes to her friend, telling her how she longs for her, and reminding her of the everlasting friendship they have vowed one another. The bower becomes the symbol of the magic ring their friendship had drawn around the two women: a secluded place for whispered confidences, affectionate glances, and playful comments about the surrounding world.

For three of the women introduced here, writing a diary is a lifelong commitment; they write year in year out until the pen drops from their fingers.

Writing becomes a habit, a way in which to remember, and in which to pin down the fleeting here-and-now via the changing seasons and the unyielding demands of daily life. The strength of the diaries lies in the matter-of-fact observation, the report of life and work on the estates and in the family circles to which the writers belong: the interaction between people, animals and seasons; the corn harvest, a cow calving, butter being churned; and about making baby clothes, or worrying over an approaching confinement, in which the lives of mother and infant were always at risk.

It was the women’s job to assist at births, weddings, illnesses and funerals. The diaries report exhaustively on the state of people’s health; information is passed on about measures to be taken in the case of illness. Despite the largely practical approach taken by the reports, however, there is also room for questions about the meaning of life, about religion, and about death.

Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta’s diary is the only extant nineteenth-century diary to offer more incisive analyses of personal feelings. Perhaps it is her, despite everything increasingly solitary, position as childless and ageing queen that causes her introspection. She was also, however, well-read and cultured, with a good understanding of the French art of letter-writing, and she had most likely learnt to analyse emotions from the examples of both Richardson and Rousseau.

Her diary thus forges a natural transition to Romanticism’s journal intime and the emerging new view of human nature.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch