By the middle of the 1990s Kerstin Ekman (born 1933) was at the top of the bestseller lists in Sweden and in several other European countries with Händelser vid vatten (1993; Incidents at water; Eng. tr. Blackwater), a novel about a bestial double murder in the sparsely populated Swedish province of Jämtland. With this novel the former detective novel writer performed a bravura in her old genre. At the same time, Händelser vid vatten is a novel about Sweden, its grandeur and piteousness, about life in a depopulated village, and about society’s slow and fundamentally criminal murder of a community. Drawn to the region where the murder takes place are a group of eccentric ecologists who live together in something like a sex sect, and in her novel Kerstin Ekman describes a sexuality akin to the intimate descriptions in Agnes von Krusenstjerna’s scandalous novels from the 1930s.

Kerstin Ekman’s oeuvre began with a number of detective novels, but developed away from the detective genre, beginning with Pukehornet (1967). At the same time, the writer brought the detective genre with her into her later novels. Kerstin Ekman invites the reader to puzzle, to hunt for clues, leit-motifs, and specific details that together breed new and unexpected connections. She can make an atmosphere uncanny: create a sensation of undefined danger, and, as in Händelser vid vatten, let her plot turn on a murder and all the powerful, dark energy that it creates.

Twisted femininity is already on display in the Katrineholm series (1974–1983), which is Kerstin Ekman’s great culture-critical history of Sweden from industrialisation and up to the present day. In the novels Häxringarna (1974; Eng. tr. Witches’ Rings), Springkällan (1976; Eng. tr. The Spring), Änglahuset (1979; Eng. tr. The Angel House), and En stad av ljus (1983; Eng. tr. City of Light), Kerstin Ekman asks fundamental questions about urbanisation, capitalism, the labour movement, and socialism. The city of the novel is the result of connections between industrialisation and the railroad, which like an umbilical cord pumps nourishment to the tiny embryo. Buildings, factories, and shops are developed and people are sucked into this growth spot. They get new tasks, new jobs, new dwellings, and they learn a new way of thinking. There is a change in social class. New masters rise, and over time everything is changed; nature, economy, ideology, and the patterns of life and morality.

In a way, Kerstin Ekman explores history by retelling it in her own words and with her own assessments – from a position where the female perspective is the natural point of departure. She follows the dramatic changes in society through the women and the children, through their observations and fates. The result is a narrative that is a strong provocation of patriarchal society, the society that is found at Katrineholm and in most other parts of the country. Ekman wonders what became of those dreams associated with the cities, and how modern human beings express their longing for beauty and meaning. What kind of society did we build? Where did the dream of the city go?

The stories of Katrineholm became an important part of the general reading of works by Nordic women writers during the 1970s. The first three volumes constituted a hopeful depiction of the social history of women. They “represented an opportunity for humanity and continuity – in spite of everything”, the Danish critic Jette Lundby Levy found in her review of the last volume (Information, 14 November 1984), in which faith in collective development has disappeared. “The present is a forfeiture of the promises written into the narrative of the development of the lower classes.” From then on, hope was found in individual resistance – and in art.

Katrineholm

Häxringarna opens with the story of a woman that history from the outset intended to forget. Her name does not even appear on her tombstone, nor do the years of her birth and death. She is named for her husband, whose name and birth and death dates are carved in the stone, along with the words ‘and his wife’. Kerstin Ekman presents her far more clearly: “This was Sara Sabina Lans: grey as a rat, poor as a louse, pouchy and lean as a vixen in summer […]. She smoked hams for the farmers. That was her cleanest job. Otherwise, there was nothing so coarse, so filthy or so foul that she was not willing to undertake it. She scrubbed down cowsheds in spring. She took in laundry and helped with butchering. She laid out the dead. She toiled all her life for leftovers and favours. She was hardy as grass, prickly as nettles.” Sara Sabina Lans, who is likened to the lowest animals and plants in nature, forms a link back to the old, pre-industrial Sweden, to a different and harsher life, to another way of thinking.

In the work of Kerstin Ekman, industrialisation, the city, competition, production, money, linear development, and the new concept of time are clearly related to something masculine. The feminine is related to nature, life in the country, reproduction, care for the living, and to an old concept of time, one where time is not money, and minutes and seconds hardly exist. Rather, time is conceived of in terms of tasks to be accomplished. As when a forty-minute delay is discussed in Springkällan: “But it had set them back forty minutes. Forty minutes! Did she have any idea what that meant? .[…] No, she probably didn’t really. Freight and passengers, long sets of train cars, important travellers, possibly royalty. The heavens and the earth trembled and all she could do was go to the market square for herring.” Kerstin Ekman often draws her imagery from the kitchen and the larder. Breasts can be “small and light like almond pastries”, a man can be “skinny like a dried stockfish”, and the sky can have ”the colour of cabbage broth”. Time can stand still like “water in a clogged sink”. And the man, the spouse, the husband, can be seen from the perspective of the housewife: “the one for whom herrings have been put to soak and cabbage parboiled, ruler of the main room, the kitchen and the hall, and of her private parts, concealed in their mid-length interlock knickers. He was the one who decided what was to be stuffed into them. He was the one responsible for what emerged from them.”

History and events are brought forward from Häxringarna through one hundred years of novel time to En stad av ljus, which in many ways departs from the other three books. A middle-aged woman, Ann-Marie Johannesson, is compelled to delve into the depths of her soul, where she meets repressed memories and images from the past. The narrative perspective has shifted drastically from distance to closeness, and the reader is exposed to a subject, a psychologically complex personality set in a complicated present. The first-person narrator is fragmented; everything is splintered, provisional, and incomprehensible, because in the now everything exists at once and with the same strong intensity. It is hard to immediately separate what is healthy and what is ill. Is she psychotic as she lies in her ecstasies?

In the middle of all this, an experiment is taking place: a literary life experiment. The human psyche, which bubbles and seethes and reacts, is placed in a kind of literary laboratory. Everything must be tested on Ann-Marie; the motherhood myths, Christianity, Swedenborgianism, mysticism, Gnosticism, quantum physics, Jungianism. What happens when you ask the great questions in life? And what does an individual do with her mystic experiences in a secular society where the spiritual and religious structures are crumbling away? En stad av ljus turns out to be a novel that elegantly contains layer upon layer of interpretations in a cleverly built structure like a millefeuilles pastry. However, all these layers come together to pose the question ‘what is it to be a woman?’

En stad av ljus can be read as a realistic depiction of a woman living abroad who returns to her Swedish origins to clear out the childhood home, auction off the furnishings, and have the house torn down. Her father has died and she considers life in the house where she was born a finished chapter, but she turns out to be wrong. Her work of cleaning and clearing-up is ongoing, and must take place in the house, with the assistance of the house, but actually concerns herself, her psyche, and is something she cannot rush.

Living in the house are people who belong to the less shining part of her past. Ann-Sofie, Ann-Marie’s uglier lookalike and school fellow, is a rather alcoholised chiropodist. Egon Holmlund, travelling magician and illusionist, is Ann-Marie’s secret and shameful dream about the dangerous male. These two shadows from the past now intrude upon her, and she must meet them in earnest within herself and within her own home.

But there are two more people in the house, two men: the Whitewasher and Gabriel, who are unusual and old-fashioned, but seem to help and protect her. The Whitewasher’s real name is Mikael Palmgren, and the two men who bear the names of guardian angels are thoroughly good and supportive. Ann-Marie has a foster mother, and a foster daughter who disappears on a trip to Sicily. Just like the mythical Persephone, who was carried off to the underworld by Hades while she was picking a flower in a meadow in Sicily, Elisabeth disappears as though she had been swallowed up by the earth into “a black hole”. She was not abducted by Hades but by Hardy, a suspected drug dealer who apparently belongs in the underworld. All winter Ann-Marie searches for her child, and when the light returns in spring she learns through an accidental telephone call that Elisabeth is alive and living in a place called Träske (‘träsk’ is Swedish for marsh or quagmire). During the summer months, she can stay with her mother while Hardy is behind bars. The Homeric song about Demeter and Persephone has been given a counterpoint in the combination of sordid detective fiction and Swedish realism.

Through names and other clues, something akin to a secret theatre is set up in this everyday inertia. In addition to stories that resemble sensational journalism, mystery plays, heavenly performances, nativity plays, and hagiographies are performed here. All are reinterpreted in astonishing and provoking ways. A mighty spectacle is put on. The novel employs a doctrine of correspondence akin to Swedenborg’s, wherein earthly phenomena have a heavenly counterpart. In Kerstin Ekman’s depiction, the modern woman is doomed to live in a society that was not built for her. She is without language: cleft, splintered, and desperate. She does not thrive in modern society, and is severely beset and exposed in a world created by men, and she finds it difficult to find a way to live.

More than anything else, Kerstin Ekman has concerned herself with motherhood. Reproduction and giving birth are mostly described with disgust: “disgust for what is breeding and hatching in all crevices and holes, even the sick and broken ones, because it tries everywhere and searches like the digger-wasp with its hatching tube for weakness to penetrate, even if it is in a festering wound.” None of the mothers in the novel series give birth to their own children. They are all foster mothers like Ann-Marie, who lets another woman give birth to her child, cook her food, clean her house, be her husband’s mistress. She rejects motherhood, wifehood, and everything that is ordinarily associated with the woman’s role. But her disgust rebounds and affects her. Slowly, she is forced to take on the tasks she previously avoided. After her walk through Hell she returns to life and has become a less arrogant, more humble, and more mature human being.

In an interview in the Swedish daily newspaper Expressen, published 26 March 1993, Kerstin Ekman stated that “sexuality and its consequences are the really radical experiences in a woman’s life.” And if one writes about love and sexuality, “one must also approach the unpleasant. The unpleasant in oneself and in the man, feelings of dissociation and hatred and disgust, and all kinds of shit”; and she cautions women against letting “Strindberg and the boys take over the descriptions of our more difficult sides. Women as abysses or vulvas that they hurl themselves into, and that suck money and life force from them.” For far too long, women have accepted the definitions of men, their readings and interpretations: “I have not understood how pervading their definitions have been,” she says in the interview.

In Kerstin Ekman’s works, one finds controversial perceptions of God and indications of the metaphysical that delineate a rebellion against the male ideologies, which for thousands of years have absorbed woman into a pattern wherein she must basically fight herself. One of the oldest literary finds, the Assyro-Babylonian myth about Inanna and her journey into the underworld, is one of the mythological texts that are secretly performed in En stad av ljus. Kerstin Ekman kept an epic poem hidden away in her desk drawer as a kind of afterbirth to the novel until 1990, when it was published under the title Knivkastarens kvinna (The Knife Thrower’s Woman). Here, the ancient myth is more clearly present than in En stad av ljus, but still works as a subtext to the story of a modern woman who is forced to make a journey to rock-bottom and then find her way back up again. “To the country of no return, of darkness, disgust, and death. They have descended to where the gates close; they have gone before us.”

When Kerstin Ekman was awarded the Selma Lagerlöf Prize in 1989, she used her acceptance speech to discuss whether her female predecessors knew deep down what they were working with:

“Yes, I am certain that they knew – while they worked with these images and concepts. They were not prophetesses who wrote randomly, although they were often forced to position themselves as ignorant beings. Nor do I believe that they were pleased to be interpreted by the male priesthood. But there were none others to be had. Another matter is that one does not have the energy to always live in the face of these insights. They have been delved out of certain depths, and that is not a place where one can permanently abide.”

(Expressen (The Express) 12.8.1989).

In Knivkastarens kvinna, the reader encounters the mutilated female body: a leaking, distressed, aching body. It has been handled roughly. “I am one of the wells you have spoiled. An anthill where spiders and wood lice have begun to build their nests.” The Song of Songs is twisted into an elegy. Doctors have carved the body and removed the life-giving organs. “Competent surgeons have opened her abdomen yet again. They have cleaned out and removed things from her. With bandages about her wrists, she is now ready to begin the descent.” Finally, she finds a place outside her body: the linen closet of the hospital ward. Here the “smell is dense and clean.” There she can sit in peace and heal. She has become “a broken vessel”, but there is healing to be found. “The large bowl enfolds the small one, the room closes itself about your precious emptiness. It is flood. The small vessel is filled by the overflowing of the greater one. You are connected.” The container, the bowl, the vessel, and the empty room are the central images of En stad av ljus, and are also the basic symbols of Knivkastarens kvinna.

In En stad av ljus, Kerstin Ekman wrote the history of modern women with a meticulous respect for documentary, though engaged in dizzying philosophy. In Rövarna i Skuleskogen (1988; The Robbers of Skule Forest; Eng. tr. The Forest of Hours), she takes on our entire history, from the Middle Ages to the Romantic movement, but in accordance with her own head and mind. Or rather, she sees and experiences it from the outside, a writer’s and artist’s entire inspiration. The compelling protagonist in the book about the robbers is Skord the troll, who takes up with the human children Erker and Bodel. They are orphans and travel as beggars. Bodel makes Skord bathe in a brook, she cuts his hair and long nails, and she washes his feet and wraps them in a piece of linen. This biblically loaded act is one that women have performed in book after book throughout Kerstin Ekman’s oeuvre. Tora cleaned F. A. Otter’s feet in Häxringarna, Ann-Sofie was a chiropodist, and even Ann-Marie finally takes on this task. “Why are you doing this?” Skord asked Bodel. She replied: “For the sake of the Mercy of Jesus Christ.”

Skord becomes increasingly human, but he does not die as humans do and therefore survives for generation upon generation. From time to time, he takes up with the robbers of Skule Forest and does things Bodel would weep over if she knew of them. He even takes part in stealing the church silver from a church. The sojourn among the robbers – that, too, a sort of descent into the underworld – comes to an end, after which he returns to start a new life with a new name and new relations.

It is the Middle Ages and the first Christianity has reached the North with ethereal religiosity and fragile Marian worship. Bodel explains to Skord:

“Mary, the rose in heaven, was the loveliness of all that lived. She was warm milk and bread hot from the oven. She was the cheese in the whey of the world. She was soft and warm like the side of a cow and dry and smooth like straw. She was pure like a well in the forest and soft like a goose breast and clear like a drop of dew on a leaf. She was the life and true happiness of all that lives and Skord asked if she was like pancakes.”

Rövarna i Skuleskogen

Skord lives for five hundred years, all told. He is in a way amoral, does not belong, and exists outside time. Skord is curious, teachable, quick-witted, and becomes the connecting link between the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, and Romanticism. He is there when people try to make gold. They lock themselves away, boil, chant, and read incantations. Skord seems to play a central part in the alchemical process. He is akin to the psychopomp Mercury, as can been seen from Skord’s winged heels. Polhem, Swedenborg, Rudbeck, Linné, all the great Swedish scientists are glimpsed. They measure and weigh and sort and write in seventeenth-century Sweden, which was so prolific in natural history. Then Skord gets involved with the Thirty Years’ War in a lacerated, dissolving Europe.

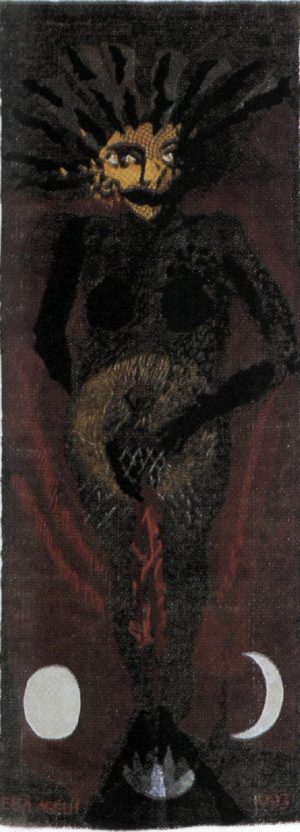

Among the robbers there is an old wizened woman, La Guapa (The Beauty), who has a deck of cards and occasionally reads a star. The deck of tarots with all its expressive images – the king, the queen, the magus, the fool, the hanged man, the star, the chariot – plays an important part in the novel.

When he is very old and very wise, he meets a peculiar and strange woman, Xenia. He falls deeply in love. “Xenia and Skord love each other like bog rosemary and hair-moss entwines – unseen by anyone, to no purpose, and without intent, they weave together.” Only when he knows love does he gain a soul, a human soul, and can eventually die.

By the end of the book, in the early nineteenth century, a genius comes up with the idea that paths of iron should be laid throughout the country. Skord speaks with Xenia: “He asked her to let her mind roam along the roads she knew, smothered in cow parsley, powdered in clouds of dust finer than snuff and whiter, far whiter. How was this winding, crooked, bending, bobbing network of roads running, as he assured her, in this same fashion, up hill and down dale throughout Sweden, to be laid with iron rails? In which smithy were they to be bent and fitted?” The man behind the wild idea of laying iron rails in nature thankfully went mad and all this will be forgotten, Skord concludes. Kerstin Ekman’s novel suite about the city began with the railroad. Here, it is dismissed as complete insanity, and its inventor winds up in a madhouse.

There is a powerful scepticism in Kerstin Ekman’s oeuvre towards the society that the railway and industrial revolution brought about. This is also apparent in the novel Gör mig levande igen (1996; Make me Alive Again), which – with group of older women in animated discussion at its centre – counsels knowledge and commitment. We have a society built by men, but hardly for men, and definitely not for women. Some resist and struggle on in competition and from ambition. Others cannot muster the energy, and turn into wrecks, physically and psychologically. But on the other hand, what would life be like if we lived alone and abandoned to a nature that is cruel and arbitrary? In Hunden (1986; Eng. tr. The Dog), a short work that came about during her work with Rövarna i Skuleskogen, Kerstin Ekman makes that experiment. A small elkhound gets away from its owner during a hunt. For a year he survives in the forest, mainly thanks to the cadaver of an elk that he comes across. His winter in the forest is a struggle for a tiny wavering flame of life, and in Hunden Kerstin Ekman describes the uttermost conditions of existence. The dog needs a home, fellowship, and a family. He needs love. So do Skord, Tora, and Ann-Marie.

Kerstin Ekman is a literary successor to Elin Wägner, and is close to her biting criticism of society and strong pathos. When Elin Wägner, in the midst of a raging war, writes Väckarklocka (1941; Eng. tr. Alarm Clock) as a counter-pamphlet, an inflammatory document in which she inventories female resources throughout history, she dares something that greatly inspired Kerstin Ekman, who in an introduction to the book writes: “In Väckarklocka, Elin Wägner celebrates a feast of thinking. In the midst of the world war, she realises that she must think as she pleases. Nothing must be allowed to stop her. Not even consideration for those allied to the feminist movement. She has read about prehistoric religions with a maternal deity at the centre, and swiftly and chaotically writes a fictional world history of women. There appears to be nothing to hinder her, nor any worries or considerations to take into account, as she sits at Lilla Björka, tired and disappointed, and writes with such joy – running completely counter to anything that at the time was called sense. For who could believe that there was any sense in being cautious of exploiting the resources of the Earth?” Svenska Dagbladet, June 1994.

Kerstin Ekman’s books are very different from each other. She keeps trying out new forms. However, they all concern themselves with lovelessness and love. And with a journey in language through continued transformation towards a core point in the human being: “a point where she is at home with herself.”

Translated by Marthe Seiden