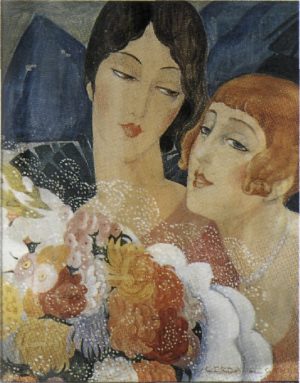

Coming-of-age novels by women after World War I often have a significant lesbian theme. The role model is frequently a single, independent career woman, described as attractive, strong, efficient, and intelligent.

In your beauty submerged

I see life explained

and the dark riddle’s answer

made plain.

in your beauty submerged

I want to say a prayer.

The world is holy,

for you are there.

Endless with brightness,

light-engorged,

I would die with you,

in your beauty submerged.

“Karin Boye: Förklaring” (Explanation) from Moln (1922; Eng. tr. Clouds).

Coming out of the closet was not without its risks. Homosexual acts were criminal offences in most countries. Until 1944, “fornication with another person against nature” could lead to two years of penal servitude in Sweden. Similarly, Swedish psychiatrists regarded homosexuality as a disease until 1979.

Finding a means of describing and expressing a sexual orientation that had been outlawed and suppressed for centuries – and that had been defined and discussed by male medical, psychiatric, and literary ‘ experts’ only – was no easy task. What the ‘new women’ of the interwar period needed, besides visibility, was a language capable of reflecting female sexual desire and experience outside the domain of men, of describing an existence beyond the ken of traditional sexual categories. One approach was to ‘borrow’ masculine traits. Another strategy was to create a ‘third sex’ with the potential of transcending and rejuvenating old notions of masculinity and femininity.

Letters and diaries of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries often glow with affectionate and loving infatuation between women, many of whom were clearly on more intimate terms with their friends than with their husbands. Romantic friendship was an esteemed institution, accepted as a way for women to practise sensitivity and moral virtue.

Attitudes changed in the late nineteenth century. Female friendship grew suspect, and homosexuality was described in pathological terms. Popular literature abounded with accounts of unfortunate creatures weighed down by the tragic burden of deformity, hapless victims of abnormal passion that inevitably led to madness and death.

Two British novels of 1928 confronted, albeit in very different ways, the new and untested lesbian identity. Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness is an account of “a man’s soul trapped in a woman’s body”. Stephen Gordon, the protagonist, feels and behaves like a man but is biologically a woman. The novel does not question any of the traditional gender roles, merely portrays them as tragically and inconsistently intertwined in the same person. The story concludes in pathos and despondency: abandoned and unfulfilled, Stephen ends up in “the well of loneliness”.

The book introduced millions of readers to female homosexuality. Its implications are consistent with the thesis of sexual psychologist Havelock Ellis, Hall’s contemporary: Lesbians are destined to lead tragic lives; their great misfortune is to be born with an abnormal urge that can never be satisfied in a way that produces lasting happiness.

Denis Diderot’s La Religieuse (1760; Eng. tr. The Nun) and Honoré de Balzac’s La fille aux yeux d’or (1835; Eng. tr. The Girl with the Golden Eyes) portray lesbian desire as evil and destructive. Les fleurs du mal (1857; Eng. tr. The Flowers of Evil) by Charles Baudelaire contains two poems entitled “Les femmes damnées” (Women Damned) that describe insatiable sadomasochistic orgies. The book was convicted of obscenity in a trial that attracted much attention, after which the poem “Les lesbiennes” was removed. Among the many depictions of lesbianism during the epoch of naturalism were Émile Zola’s Nana (1880; Eng. tr. Nana), Alphonse Daudet’s Sappho (1884; Eng. tr. Sappho), Guy de Maupassant’s short stories, including “La maitresse de Paul” (Paul’s Mistress), Pierre Louÿs’s Aphrodite (1894; Eng. tr. Aphrodite), and August Strindberg’s Le plaidoyer d’un fou (1887-1888; Eng. tr. A Madman’s Defense).

The other novel of 1928 was Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. The playful, subtle, mischievous, and yet serious narrative follows the exploits of the title character, who can switch gender as easily as changing clothes. Orlando lives through various historical epochs, always bisexual, whether as a woman or a man. Like an ethereal, happy-go-lucky androgynous being, a Tintomara figure, Orlando drifts between sex roles – which shift capriciously from one age to the next.

The theories advanced by sexologists Richard von Krafft-Ebing in Psychopatia Sexualis (1882; Eng. tr. Psychopatia Sexualis) and Havelock Ellis in Studies in the Psychology of Sex: Sexual Inversion (1897) lent scientific legitimacy to the accusations of mannishness and lesbianism that were levelled at the new self-supporting women and feminists of the interwar years.

The Well of Loneliness, which was both prosecuted and notorious in England, found a wide readership. Woolf’s sophisticated fairy tale never achieved the same popularity – or legal problems. Perhaps the plot was too fantastic to be taken seriously.

The expression “Boston marriage”, which was used in the United States to describe two unmarried women who lived together for a long period of time, originated with Henry James’s novel The Bostonians.

Of the Same Blood

Growing tolerance in the interwar years applied to heterosexuality only. In the 1930s, it was still virtually impossible to publish fiction about a fulfilling lesbian relationship. Agnes von Krusenstjerna learned that lesson when Av samma blod (1935; Of the Same Blood), the seventh and last volume of her Pahlen cycle, was brought out. The reaction was savage. Krusenstjerna was branded as amoral, abnormal, psychopathic, and mentally disturbed.

With the exception of pornography, the book contains the first female sex scene in the history of Swedish literature. It created a sensation by virtue of its boldness, and the book was accused of obscenity. However, the Minister for Justice refused to prosecute.

The story begins with Agda trying a skirt on Angela, who is in late pregnancy. Agda is also expecting, though it is too early to tell:

“Suddenly Agda embraced Angela with trembling arms. The skirt fell at their feet. She no longer cared about it. The scissors jingled as they hit the floor. The room grew silent. Agda felt as though she were holding life itself in her arms. She was brimming over with tenderness for this body and the new being it was nurturing. With a little sigh, she laid her head in Angela’s lap. Angela stroked her hair. It was as though they enclosed each other. The embrace united them in an extraordinary way. All the affection that had gathered force inside them suddenly blossomed. They loved each other.”

When they talk about their love and try to understand what has happened, Angela exclaims in sudden despair: “We didn’t do anything wrong, did we? It was so beautiful, so sweet. How could it possibly have been a sin?” The answer she receives is a wordless embrace: “And her anxiety evaporated. There had been nothing sinful about those gentle kisses, those fond caresses, that sorrowful embrace. It was as though they were all alone, far away from other people, deep in a forest that murmured to them amiably from every direction.

“‘Don’t ever leave me,’ Angela whispered. ‘I can’t bear the thought of it.’

‘Never,’ Agda reassured her.”

Their feelings evoke unfettered and unspoiled nature, youth, beauty, and health. Dark, “ill-fated” love between women – which traditional sexual psychology had regarded as a portent of tragedy and mental illness – was seen in a new and favourable light.

Sigmund Freud’s Über die Psychogenese eines Falles von weiblicher Homosexualität (Eng. tr. The Psychogenesis of a Case of Female Homosexuality) was published in 1920. Psychoanalytical theories were increasingly familiar and discussed at the time. Freud’s concept of the role that early psychosexual development plays in shaping personality had a revolutionary impact. He explained homosexuality as a neurotic disorder, often caused by repressed childhood traumas, rather than a congenital, incurable “inversion” in the spirit of Ellis.

A Tomboy’s Tragedy

Charlie was the first work by Margareta Suber (1892-1984) and the first Swedish novel with lesbianism as the main theme. The title character is a young tomboy whose sexual awakening brings her to the painful realisation that she nurtures forbidden urges. A secondary theme of the book is the reaction of a heterosexual to the love of another woman. Charlie is largely observed and interpreted from the heterosexual woman’s perspective.

Both she and others regard Charlie’s sexual orientation as a misfortune that has afflicted her through no fault of her own. Charlie herself is portrayed with incontrovertible compassion and warmth. She radiates charm and vitality whether she is romping with children on the beach, playing with her bulldog puppy, or driving her purple sports car with supreme confidence. On the surface she is a typical specimen of “the new woman”, cheerful and sporty, liberated and enterprising.

Sara, with whom Charlie falls in love, is the mother of two children. Mature and maternal, she soon notices that Charlie’s hearty exterior conceals an abandoned child, lost and confused. She takes Charlie under her wing and offers her friendship, although neither of them suspects “the dark riddle” lurking beneath the surface. When her young daughter develops a jealous crush on Charlie, Sara begins to experience a wrenching, insidious feeling about something she can neither see nor understand. She feels ill at ease when Charlie wants to hug and touch her but does not know why until the young woman surprises both of them one day by embracing and kissing her with the “ardour of a man”. Sara is frightened and backs off. Charlie is still unconscious and innocent enough to regard her love for Sara as a joyful event: “How Sara shines – her hair, her eyes, her smile. She makes me feel warm and bright, I want to be endlessly good.”

“‘Darling,’ Angela said out loud… Her fingers clutched Agda’s, her blood pounded, and her muscles tensed. Her desire, which had grown and intensified with her pregnancy and long abstinence, awoke in all its strength. At first she was terrified, then elated. Slowly, quietly, without shame, she shifted ever so slightly as if to bring her groin closer to Agda’s. Boldly as if that was all she had been waiting for, Agda squeezed her leg between Angela’s.

“They shared a moment of ecstasy and gasped with pleasure. Their fingers dug into each other.”

(Agnes von Krusenstjerna: Av samma blod)

Charlie finds heterosexual relationships disgusting, as explained in a rather glib Freudian manner by a disagreeable childhood memory of pornographic pictures that a male classmate had shown her. The book hints that traumatic emotional ties with her father have had an even more profound influence. After her mother’s premature death, her father – a wealthy businessman – claimed her for himself. Charlie, who tries to fend off his demands and importunate masculinity, is on the run from him when the story begins.

Albert Bonnier’s Publishers were hesitant to bring out a novel with such a sensitive theme as Charlie. But the book was well received. “The delicate subject [was handled] with intelligence and good taste.” (Dagens Nyheter) The review described Charlie as a “charming, little, soulful person with a serious problem.” The critic for Svenska Dagbladet saw her as “an interesting psychopathic borderline case.”

The account of their relationship differs markedly from The Well of Loneliness, in which Stephen strongly identifies with his father at an early stage. Hall’s novel, which was widely discussed at the time, no doubt inspired Suber. Nevertheless, her roguish and dapper heroine possesses none of the frosty bitterness and dogged gallantry that characterises Stephen, who is ultimately reconciled with God: “God must have had a purpose for creating me the way she is.” Charlie ends with the ambiguous words: “Her body was now ready to begin living the life for which God had created her.”

After Charlie, Suber wrote a number of psychologically astute novels that revolved around women and marriage, including Ett helsike för en man (1933; Hell for a Man), Du står mig emot (1939; You Walk Contrary to Me), Jonna (1940; Jonna), Vänd ditt ansikte till mig (1942; Lift up Your Contenance upon Me), Alla bära de svärd (1947; They All Carry Swords), Äkta paret ut (1958; Married Couple Out), and Leva på italienska (1976; Live in Italian). She published Böljegång (1980; Billowing of the Waves), a poetry collection, late in her career.

Right or Wrong – There Is Something Called Necessity

Karin Boye’s Kris was the first Swedish novel with a lesbian theme by an openly homosexual woman. Twenty-year-old Malin Forst, a student at a training college, cries easily, gives in easily, lets her inferiority complex get the better of her. “You I hate, / you my wretched willow-being, / you that twine, you that twist, / patiently obeying others’ hands,” Boye wrote in Moln (1922; Eng. tr. Clouds) when she was young. The other female character, the object of Malin’s love, is draped in soft, lyrical symbols of nature.

Kris is based on Boye’s memories from her days at training college when she was twenty years old. She wrote it ten years later, after psychoanalysis in Berlin had convinced her to honour her sexual orientation. The book reflects her long journey from the daring rejection of traditional faith and morality in her youth to the conscious choice of a lesbian lifestyle in middle age. The psychological price she paid is evident in the enormous tension between the novel’s mystical language and the forces that swirl around the narrative. Not all readers had a clear understanding of what Kris was all about. Many of them regarded it simply as an ideological repudiation of Christian asceticism and obedience.

Malin starts off as a devoted young Christian, but suffers a severe episode of anxiety and experiences herself as “deserving of eternal damnation”. The turning point occurs in the middle of the novel. Malin refuses to admit, even to herself, that she has a crush on her classmate Siv. The book never uses words like homosexual or lesbian. Malin regards her feelings as beyond previous concepts with their overtones of sin and abnormality: “Lips, can’t you shut so tightly around the inexpressible that no words stick out their hateful smallness and muddy the waters. Don’t give it a name, let it be as it is, in my blood and my eyes, like life and sap.” Malin’s rejection of accepted morals is a rebellion against both her father and God. She takes the side of the oppressed against the powers that be.

Her feelings for Siv, the friend whom she loves and adores at a distance, find expression in the vocabulary of nature, health, light, and joie de vivre. Inhibited and repressed, Malin looks up to Siv as a positive role model of dynamic, unquestionable integrity: “She grew with absolute faith in the secret, intrinsic law of her being.” As opposed to the label of criminality and abnormality that traditional morality had pinned on homosexuality, self-affirmation offers Malin a path to health and joy. Her spiritual crisis does not lead to an actual relationship, but to a new inner strength that instils self-confidence and trust in her own moral compass: “Right or wrong – there is something called necessity. My necessity. My will. Consciousness: this is me, this is mine.”

Merit vaknar (1933; Merit Awakes) and För lite (1936; Too Little), Boye’s novels about marriage, camouflage the lesbian theme by turning the protagonists into heterosexual couples. In the case of Merit vaknar, she later regretted that she had been too “cowardly” to reveal the whole truth. She examines the problem in the short story “Författaren som ljög” (The Author Who Lied) from Uppgörelser (1934; Reckonings), but once again adapts the relationship to heterosexual norms.

Be Silent, Work, Forgo

Freud’s theories heavily influenced Norwegian literature starting in the late 1920s. The vitalist dream of “the open lifestyle”, most clearly articulated in Sigurd Hoel’s Syndere i sommersol (1927; Eng. tr. Sinners in Summertime), was based on the new doctrine of sexuality as integral to free, uninhibited personality development. Nevertheless, lesbianism appeared openly in only one Norwegian novel of the interwar years: Følelsers forvirring (1937; A Confusion of Feelings) by Borghild Krane (1906-1997).

“Loneliness made its abode in her, not for one or two days, but forever. Every now and then, the sense of isolation turned her to ice, and she couldn’t believe that anything could be so dreary.

She walked down the street like someone who needed to protect herself. But it didn’t do any good. She saw only half of the world, women and nobody else. Men were like shadows. Only women possessed life.”

Borghild Krane: Følelsers forvirring (1937; A Confusion of Feelings)

Krane was a well-educated career woman who started off as a librarian and later became a physician and psychiatrist. Her protagonists are decidedly ‘new women’: middle-class professionals who spend their lives in offices, classrooms, university libraries, rented rooms, and their own small flats, as well as travelling. But their careers provide them with neither emotional satisfaction nor self-esteem.

Despite the pioneering nature of the novel, the two protagonists never consummate their relationship. The book may be interpreted as a resigned appeal to understand and show compassion for those who are ‘different’, an affirmation that they are also human. One of the characters dies and the other sees the rest of her life as a commandment to “be silent, work, forgo”, to remain alone.

Krane later published the novels Det var engang en student (1940; Once Upon a Time There Was a Student) and Håbets tegn (1948; Signs of Hope), as well as the short story collections, Tre unge kvinner (1938; Three Young Women) and Kvinner selv (1972; Women Themselves). She also published studies about the writings of Amalie Skram and Sigrid Undset.

“The Dark Riddle” in Crime Literature

Maria Lang – the pseudonym of Dagmar Lange (1914–1991) -– published more than forty crime novels in as many years. At that pace, it goes without saying that her writing came to be formulaic. Her speciality was the whodunit à la Agatha Christie, with artfully constructed plots and subtle clues. Chief Inspector Christer Wijk could have come right out of the classical British detective novel. The suspects are usually confined to a small circle of acquaintances whose semi-secret sexual escapades provide the key to solving the mystery.

Lang’s first novel, Mördaren ljuger inte ensam (1949; The Murderer Does Not Lie Alone), caused a great stir due to its daring subject matter. At that point in history, few readers could possibly suspect that a crime of passion whose victim was a beautiful, sensual woman had been perpetrated by another woman. Wijk’s powers of deduction allow him to uncover the true motive, jealously, and ultimately lead him to the murderer. Intellectually, though, he cannot get past old ways of thinking. He assumes that the two women had been rivals for the same man.

Viveka Stensson, the accused, comes clean at the end of the novel: “I suppose that my instincts from the very beginning were what you would call abnormal.”

Her confession to the double murder turns into a kind of plea for the right of lesbians to live as they please. Homosexuality was decriminalised in Sweden five years before publication of the book. Nevertheless, the extraordinarily popular novel confirmed old prejudices. Its basic tenor was as clear as can be: lesbians are abnormal, and the inevitable consequence of their desires is tragedy.

The title of the book is based on the implicit assumption that lesbianism is so unnatural and offensive to a normal man that he would rather be suspected of murder than reveal his fiancée’s relationship with another woman.

Thanks to Lang, “the dark riddle” became a legitimate subject of popular literature. The amorphous threat of “perversion” coalesces into an insidious, destructive energy. The male detective represents established law and order. But he cannot locate the hidden key to the mystery on his own. Only the murderer’s confession can reveal the truth. Therein lies the fascination of the novel.

Dagmar Lange was thoroughly versed in the history of homosexuality. Her 1946 doctoral thesis was about Pontus Wikner (1837-1888), a Swedish philosopher and author who was inspired by classical Greek literature.In Psykologiska självbekännelser (Psychological Confessions), not published until 1971, Wikner frankly discussed his homosexuality.

Translated by Ken Schubert