The writing of Rut Hillarp (1914-2003) is suffused by refined erotic mysticism, far from the primitivist sexual Romanticism of the 1930s modernists. Three books of poetry published in the 1940s comprised her first phase and four works of prose in 1951-1963 her second phase. After nineteen years of silence, she returned with three books of poems and double-exposure photographs.

Hillarp attended secondary school in Lund in the early 1930s. “Gymnasiststad” (Upper Secondary School City), the poem in her first book that traditionalist critics most related to, was written in the spirit of Bo Bergman, Vilhelm Ekelund, Erik Lindorm, Dan Andersson, and other Swedish poets after the turn of the century.

Rut Hillarp grew up in Hässleholm, a small town in which revivalism had a strong hold. Cinema and dancing were sinful, the Second Coming and Heaven and Hell were fearful realities. Her mother was an itinerant evangelist, and her father (Nils Bengtsson, an ironmonger from Hillarp) founded the Swedish Missionary Society congregation in the town.

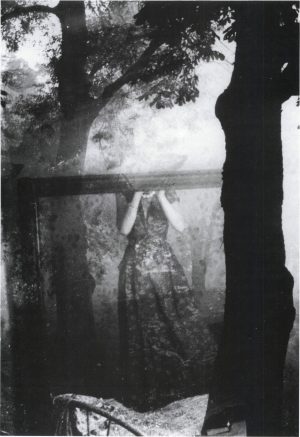

Newly married, Hillarp moved to Stockholm in 1932 at the age of eighteen. She studied linguistics and the history of literature and received a licentiate degree in philosophy for her dissertation on Verner von Heidenstam’s novel Hans Alienus (1892; Hans Alienus). Solens brunn (1946; The Sun’s Well), her first book of poetry, was brought out the year she began teaching upper secondary school. Meanwhile, the new Swedish modernism was getting off to a stormy start. With its emotional force and evocative imagery, Erik Lindegren’s Mannen utan väg (1942; The Man without a Way) was a major source of inspiration for Hillarp. Particularly striking about her poems was the erotic mysticism and the ‘double-exposed’ imagery: sensual/sacred, corporeal/cosmic

Oh wandering pillar

whirlpool of pain and pleasure

break the bows of your rhythm against my transparent veins.

Was it erotic self-worship or erotic mystique, the captivity or death of the ego? “Shackled to the cliff I await him night after night.” Hillarp’s poetry is both moving and profoundly unsettling. Among her female characters are Prometheus, Alcestis, the women at Jesus’ grave, and Isolde. Her mystical approach is characteristic of the age: a sequel to James Joyce and T. S. Eliot. But she has her own unique themes – flames of passion and vulnerability, emptying the well of the sun, looking for a man and embracing his echo, the taut bow of expectancy.

What do you review – the poems or the women poets? A long article by Ebbe Linde in Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfartstidning on 3 June 1948 discussed nine female poets, including Hillarp and her Dina händers ekon:

“You genuflect in admiration for Eva Wichman, commit suicide with Solveig Johs, and propose marriage to Martha Larsson. All three poetic temperaments are decidedly virile […]. But Rut Hillarp is a woman from head to toe […]. Larsson’s poetry can be sensual as well but is most reminiscent of a suntanned young woman swimming in the summer ocean, whereas Hillarp reflects the cadences of lovemaking itself, with a touch of the highest spirituality.”

Gunnar Ekelöf wrote of her kinship with erotic poet Erik Johan Stagnelius (1793-1823), their vacillation “between spiritual sensuality and sensual spirituality”, their eroticised experience of life. But the glue that ultimately holds Hillarp’s poems together is the “now” – from the prayer in Dina händers ekon (1948; The Echos of your Hands) about a moment of love that leaves death in its wake to “Eurydike” (Eurydice) in Spegel under jorden (1982; Mirror under the Ground), which marked her return as poet and author:

Shut in, shut in

I hear my blood pound in the walls

I cry for a door

but there are no doors here, no windows or ceiling

only walls, walls

shrinking, hardening walls

Where am I?

in which room?

Is this his heart?

Only for a moment did he turn around to see me.

Only for a moment was I real.

My life lasted for a moment.

Between emptiness and powerlessness.

Such longing is not a death wish or denial of life, but rather ritual transcendence. Isolde, the representative of fatal love, first appears in an extraordinarily sober connection: “Råd till Isolde” (Advice to Isolde) in Solens brunn. A union of lovers who die at each other’s side is out of the question; that romantic dream sabotages reality. Nevertheless, the dream is not wholly banished from the poem. Art is nurtured by the transcendent power of dreams. As Hillarp subsequently asserted in an interview, the task of poetry and dreams is to transform life into wonder.

After printing five hundred copies of Blodförmörkelse, Hillarp made the rounds of Stockholm’s bookshops and sold most of them. Artur Lundkvist and Eyvind Johnson of the Bonnier’s grant committee arranged additional financing, with which Hillarp published a second edition of four hundred. Be that as it may, Bonnier’s failed to snap up her next book, Sindhia, which became a Norstedts bestseller instead.

Alienation and the Total Eclipse of the Blood

Blodförmörkelse (1951; Total Eclipse of the Blood), Hillarp’s first novel, uses condensed language to tell the story of a love affair. No matter how extreme the relationship may seem, the novel addresses the fundamental question posed on the back cover: “What is love anyway?” Is it an escape from ourselves? Or are we always the prisoners of our own fantasies?

The male protagonist lives outside the myth of romantic love. Love for him is an art, a creative act, a profession: “I’m not an egoist; I don’t educate women for my own sake.” For the female protagonist, love inhabits two different spheres: red for its human aspect, happiness, and black for that which is beyond the individual, non-subjective experience, pleasure: “The dark sweetness of submission that tightens my skin and lowers my eyelids.” Black and red define each other and require certain “illusions”: the man’s need to dominate, his affinity with God, his capacity for love: “that he somehow loved me and wished me well despite everything, that he was a fellow human being.”

The woman is the subject in both senses of the word – subordinate and independent agent. Subdued, dominated, certainly. But she is the author of the desire, the demand for submission that crushes her. She is the one who interprets the world and creates meaning. Ultimately, she is enslaved only by the illusions that she herself begets. The novel’s most profound problem stems from this insight.

The lean, incisive form of Blodförmörkelse lays bare the foundations of love – desire imprisoned by imagination. In the poetic equation, the woman becomes the man’s fantasy of the Other, the imperfect, alien object of desire and contempt: “You are the illness whose name is woman.” The woman assumes that position, but on her own terms. She turns objectification, deference, into her own project, transforming passivity into activity. She takes form, realises herself, through the man’s desire. Her only condition is that he love her, or that she is able to maintain the illusion that he does. Meanwhile, his desire or gaze elevates her beyond herself. Though sex, she exposes herself and surrenders to transpersonal, non-subjective experience. Now the condition is that he is willing to be defined as an inaccessible subject: the incomprehensible, unintelligible Other.

Blodförmörkelse recounts both the seduction and alienation inherent to this erotic project. The pleasure of sex beyond the human realm can be captured in lyrical prose.

But the alienation is stronger and the blood is eclipsed. The book culminates with a condensed nightmare in “the laboratory”. The experiment has failed. The male scientist’s project has generated infinite copies of a woman – mass circulation of the stereotypical Other. The woman’s project isolates her. She is ensnared in the imaginary gaze that turns out to be a mirror and nothing else: “And I would see in his face everything that I know is not there. And his eyes would follow my face’s reflection of a reflection.” His real countenance is inaccessible. The woman is imprisoned in her expectation and image. When she finally phones him, she hears her own voice on the line.

The extent to which Blodförmörkelse was an unnerving and radical departure from the fiction of the time is evident from the fact that Hillarp had to self-publish it. Both Albert Bonnier’s, her previous publishing house, and others backed down. Her modernist style was not the decisive factor – experimental prose was in its heyday – but rather her erotic experiment, the radical representation of sexual fantasies, desire exposed by a member of the ‘inferior sex’.

Like other writers who started in the 1940s, Hillarp was accused of having “a confused emotional life” after publishing her first book. That literally kept her from receiving the highest evaluation during her teacher’s training year. Nor did her classmates at Martin Lamm’s licentiate seminars in Stockholm have any feeling for “incomprehensible” poetry. They were endlessly amused when the magazine 40-tal (The Forties) accepted a couple of her poems in 1945. One poem starts off:

“On the dark and dizzying journey, he politely kissed my ear.” Her male classmates patted her on the back and explained: “When a man kisses a woman’s ear, he is highly aroused; you can hardly call him polite.”

Nevertheless, critics received the book well and were clearly moved. Sindhia (1954; Sindhia), her next novel, was more realistic and accessible, regarded by many as a high point of her career. The book analyses emotions in greater depth and concretises the interplay between women and men. The conflict between sex as ritual and the more altruistic aspects of love takes on sharper contours.

Sindhia, a modern career women and ancient priestess of a heathen fertility cult, has chosen the artist Reger as the Man, the absolute Other. One side of her is the supreme manifestation of alluring femininity: “Sensuality so conscious that it turned ironic: you are welcome to look, kind sirs, but don’t come any closer. Do you have any idea what lengths such insatiability can drive me to?” Only Reger can call forth the other side of her, the voraciousness that takes her beyond all boundaries.

On the surface, the two sexes are equal or should strive to be so. But sexuality is subject to other laws. “To be ruled and dominated. Sexually, not in other respects.” A battle, a ritual of sacrifice with a foregone conclusion: “… helpless – I love to see you as helpless as a woman, then rise to your true stature and twist the smile out of my hands.” Not degradation but self-effacement, a longing for the absolute that seeks satisfaction in sexuality.

The lover in Blodförmörkelse is egoless, a tool, a presence at the disposal of the female protagonist. Despite its eccentricities, the love affair is a genuine pact, a partnership. That the male protagonist in Sindhia is more normal gives rise to other problems.

The reflections are more insidious and difficult to separate. “You rewrite everything”, the man says. And thank God for that. The man is to be the ruler and the cosmic order, the instrument for elevating the woman to a state of ecstasy. Meanwhile, he is to be the one who watches and receives. Traditionally, the man has had the privilege of “rewriting”: the woman has been the symbol, the container, the metaphysical representative. In that sense, reversing the direction of such wishful thinking is an act of liberation. Nevertheless, the man’s situation evokes compassion: “Don’t look at me as if you were expecting a sacrament.”

The Ideological Novel of Heathen Mysticism

En eld är havet (1956; The Sea Is a Fire) divides the various aspects of femininity between three women. Rakel represents the instinct for self-effacement and the absolute, Charlotte chooses – at least ostensibly and in the long run – intimacy, and Cynthia is the mouthpiece, the interpreter of sexuality as myth and ritual. Judged as a narrative novel, subject to the demands of characterisation and insight, the book may appear to deviate from the poetic forms of expression and perception that Hillarp specialises in. A more fruitful approach is to regard it as an ideological novel, the embodiment of a system of ideas – erotic metaphysics, sex as a ritual of sacrifice, “heathen mysticism” in the words of theologian Olof Hartman. The desire for submission is shorn up from every side – an inheritance from the capricious despot of Christianity and the Old Testament, a product of women’s oppression for thousands of years, guilt feelings instilled in early childhood, father fixation, an activity essential to the genesis of meaning. But the novel also tackles the second question: the relationship between play and seriousness, ritual and reality.

Hillarp has been compared with both Edith Södergran for her erotic poetry and Karin Boye for her sexually charged spirituality. The ultimate objective is guilelessness. The experience of pain and ecstasy is a means of becoming more receptive: “When you are open, God arrives.” The mystical ingredient of the poem is the establishment of a link between human beings and the cosmos.

Hillarp accomplishes that feat most thoroughly in her books of poetry and photography, Spegel under jorden (1982; Mirror Under the Ground), Penelopes väv (1985, Penelope’s Web), and Strand för Isolde (1991; Beach for Isolde). Short, condensed poems evoke sexual experience, transparent and unadorned. Ancient and medieval myths serve as a compass for following the twists and turns of desire. Momentary passion is elevated to the realm of eternity. The keynote is melancholy.

Translated by Ken Schubert