The cover of Vita Andersen’s (born 1942) second poetry collection Næste kærlighed (1978; Love Thy Neighbour) shows the outline of a woman’s face; where the features should be there are blank, empty spaces, and below the face is a barely visible bit of shoulder. The hair, on the other hand, is heavy, dark, and wig-like. In front is a collage of lipsticks, sweets, eyes, cigarettes, lotions, TV, a burger, artificial sweeteners, and a mouth open wide to eat a giant cream cake. The image summarises the women’s portraits from her first books, the debut poems Tryghedsnarkomaner (1977; Security Junkies), the short stories Hold kæft og vær smuk (1978; Shut Up and Be Beautiful), and the plays Elsk mig (1980; Love Me) and Kannibalerne (1982; The Cannibals), which are about women whose identity is tenuously anchored in appearances, in their clothes, things, and the looks they receive from men. Their identity is constantly on the verge of collapsing. In the short story “Iagttagelser” (Observations), the anonymous woman begins her day by checking out her body and her well-appointed flat, and then on her way to work she suddenly turns back, crawls into bed, sleeps, drinks, pees in her bed, and makes a half-hearted attempt to kill herself in the bathtub. Then, on another morning, she goes back out into the world covered in heavy makeup: “Again she saw herself in all the windows. A man she passed didn’t turn around to look at her. And she was frightened that she was no longer as beautiful as she once had been.”

Settings are ambiguous in Vita Andersen’s writing. In the media, she came out with the dramatic tale of her path to becoming a writer, which passed through adoption, orphanage, random jobs, daydreams, psychiatrists, and little notes that she finally dared to show to the world. The staged life was part of the fiction, of the recollection of a life of masks as well as a strategy to cope with popular interest.

Tryghedsnarkomaner tells about the interaction between the sexes in a demonstrative prose form that was nicknamed knækprosa (broken prose) because the poems were apparently nothing more than narratives made up of lines of uneven length. However, Vita Andersen’s narrative and characterising poetry is more complex than it initially appears. It is in itself a staging of everyday language, an exhibition of the force, the roles, and the confinement in the lives and speech of the characters, but by no means an artless repetition.

The gender roles as a guarantee against a happy interaction between the genders is a central theme in her texts, which often concentrate on the initial manoeuvres, on dating, and affairs, where any spontaneity is rendered impossible from the outset due to mutual expectations (“what do you think, I think”) and conflicting hopes, which the social roles force the parties into. Images of gender, of the masculine and the feminine, which they try to live up to and which each desires in the other come between them. However, the gender difference is not just social: behind the closed, ambitious men and the posing, cracking-up women is a childhood that is unravelled again and again in Vita Andersen’s texts, and then finally unfurled in all its complexity in her novels. In Hold kæft og vær smuk, girl after girl is fatally let down by a mother figure who is so monstrous, alcoholic, lascivious, indifferent, or mentally unstable – such as in “Lampeskærmene” (The Lamp Shades) – that the caring relationship is on the verge of being reversed. The problem lies in this failure, which becomes the socio-psychological explanation for the battle of the sexes and, especially, for women’s pain; and it becomes the inner picture of the abandoned/despised child that turns out to be the answer to the adult’s questions about the origin of suffering. This suffering dominates the unbalanced love relationships and the adult women’s agonising relationship to their body’s double life as aesthetic surface and inner desire for food and sex. However, it also spills over into their social life, where they are split between a constant striving for order and the constant threat of chaos.

“Fejlen” (The Mistake) is the first of the five short stories for girls in Hold kæft og vær smuk (1978; Shut Up and Be Beautiful). Here, a first-person narrator reports how, at the age of twelve, she diagnosed her life by combining two stories: an acquaintance’s story that the mother had never been caring and loving towards the girl when she was little and an account in Reader’s Digest of the importance of the earliest years in a child’s life. The mother’s love goes to the son, and the never-loved daughter exchanges reading material for cookbooks, for fantasies about the food that the women in the texts tuck in to, despite their desires to be thin as models, to fill the emptiness.

Rape, rather than love, is the male response to female vulnerability. It demonstrates the dangerousness of the world, its indifference, and its exploitation of the female body, which is given additional reasons for protecting itself and shutting out the world. Violence is the externalised counterpart to fear: woman after woman is raped in the first poem, “Laila og de andre” (Laila and the Others), in Næste kærlighed. The damaged body forms the starkest contrast to the dream of the perfect, flawless, and unchanging body. However, the body is just as vulnerable as the soul, it becomes the visible symbol of destruction, of lack. The women seek comfort in sweets (for the body) and weekly magazines (for their fantasies). Both are soothing, but as the thin bodies in the fashion photos pass across the pages, the readers’ bodies swell up. In their attempts to keep the sense of privation, discomfort, and fear at bay, the women ritualise their lives, and perhaps the poems’ detailed reproduction of the rituals become frightening simply because the nightmare of a woman’s daily life that they reproduce looks unmistakably like – everyday life. The informal verse turns out to have compulsion, the logic of neurosis, as its form.

Mother and Daughter, Mother and Son

Neither the texts nor the women in them receive answers to or names for their sense of privation by flip-flopping between rituals and chaos, and in her novels about children, Hva’for en hånd vil du ha (1987; Pick a Hand) and Sebastians kærlighed (1992; Sebastian’s Love), Vita Andersen examines the sphere in which the sense of privation originates. Hva’for en hånd vil du ha is about nine-year-old Anna’s passion for her mother Melissa, who is again obsessed by her dream of a rich lover who showers her with money and clothes, desire and admiration, in short, an annihilation of the passage of time. The novel can be read as a family saga where Melissa’s tragic childhood becomes a social and psychological heritage that her daughter cannot bear to witness. However, the outer historical dynamics constantly lose ground to the inner domestic triangle between the mother, the daughter, and desire.

The title refers to an episode in Melissa’s childhood. As a little girl, she was encouraged by her father to dance in a bar: he showed her off, and during that period he did not beat her and her body remained intact. When she grows older, he drops her. She continues to dance in secret, but is discovered and the father says: “pick a hand.” The choice turns out to be a choice between being beaten and being beaten even more. Melissa must care for her many little brothers and sisters as the mother is practically non-functional; everything in the home is described as disgusting and wretched, the beds are filled with babies with diarrhoea, their clothes are in shreds – with the exception of the dancing girls’.

It is a story about a social tragedy, but especially about how dance, the staging of the body, is the only protection against filth, violence, bruises, and poverty. Alongside the image of the dancing girl in the nice, clean clothes is a family portrait without mitigating circumstances: father, mother, and children is a scene in which the only exchange is hopelessness. It is not until she has her daughter Anna that Melissa finds unconditional love, a care that is independent of her performance in life in general. But the only thing Melissa can perform is the dream of the beautiful body of her past, which she relives for a brief moment when a rich lover waits on her at an expensive hotel. For the second time, Melissa runs away from her family towards a life of beauty, only now it is from the grime and mess that she is personally responsible for, and from a husband who has been forced to take over some of the “housewife” functions that Melissa rejects. And from Anna, her own neglected child.

When mother and daughter finally find each other, it is in the wasteland of sociality and normality where Anna takes over more and more of the mother’s functions for Melissa, who increasingly resists the reality, the conditions for survival. As she approaches old age and wrinkles, she regresses to the helpless state of a child until she finally sends Anna out to get help from an adult for the two children, neither of whom has the prerequisites to be the adult, the mother, to the other.

The double portraits of Anna and Melissa lead Vita Andersen’s women beyond the constant shifting between ritual and chaos. When, after the last exertions, Melissa finally gives up the dream of returning to youth, beauty, and motherhood, she capitulates in a way to the reality in which she could only survive by remaining in her illusion. The superficiality that Vita Andersen’s female characters live in must always be seen as a rigid and partially failed social facade that can only be maintained in short bursts: it is without history and the only principle of time it recognises is repetition (and decay). When they let it go, regression, psychosis, and death await. It would be too much to say that the Anna character represents hope, but in her constant and stubborn love lies a strength that brings her beyond pity and pretence.

The text and Anna have a go at the motherly body, which must change when subjected to this perseverance. The careless, painted, self-absorbed whore-mother who neglects husband and child becomes more and more frail in her hotel room, where she manically surrounds herself with new clothes while she waits for her lover and is besieged by her child, whose insatiable, but also devoted, desire for the mother represents the first genuine desire, which the adult woman then transfers to men. Anna finally breaks down the barrier – when the mother becomes a child again.

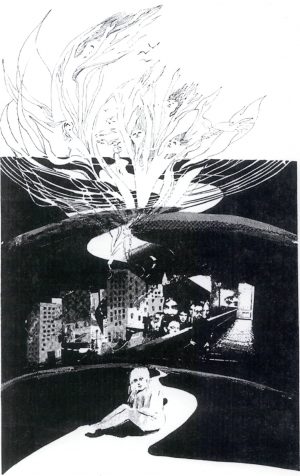

Anna besieges her mother in the hotel room in Hva’for en hånd vil du ha (1987; Pick a Hand).

“She opens the door, and the child jumps into her arms.

Anna held on so tightly, like a little animal. I need to get rid of her, she thought, but how. The poor thing.

‘Anna,’ she said, ‘listen to me.’

The child began to scream and clung to Melissa so tightly it hurt.

When she managed to wrench an arm or a leg free, the child grabbed hold somewhere else.

‘Anna, you’re choking me.’

The child grabbed her hair, and Melissa slapped her on the hand. She held on so tightly that when she moved her hand after the slap, she tore out a tuft of hair.

‘Mummy, Mummy,’ she screamed, ‘but where can I go?’”

What Vita Andersen in her writing attempts to extract from the ruins of family history and woman’s identity turns out in Sebastians kærlighed to be nothing less than a love utopia, the key to which she never finds in the external social space. There she only finds commodities, money, glitter, conventions, and a seamy underbelly of poverty and horror. However, in the closest relationships between mother and child can be found resources that yet have a foundation to build on. Sebastian’s mother Carla is an artist. As the daughter of a dancer who filled her rooms with pictures/mirror images of herself, Carla becomes an artist in order to create her own images of the mother. During the process, she breaks free of the monotonous narcissism, just as when she and her son gaze deeply into each other’s eyes, finding their own reflections in the eyes of the other. The gaze differentiates Carla from Vita Andersen’s other female characters: with the gaze, she moves from the surface to the dimension of depth; she creates portraits of others and aims her gaze outward. In so doing, she occupies a dynamic triangle between art, love, and the child Sebastian. And when Carla is seen through Sebastian’s eyes, the changes in her body also become a positive feature of her gender.

Sebastians kærlighed (1992; Sebastian’s Love) is about puberty as a dangerous limbo on the verge of psychosis, a denial of reality, and adaptation. Sebastian finally chooses school rather than complete mental breakdown, but there can be no reconciliation between the worlds of the child, love, and fantasy.

The child’s universe is the universe of victims in Vita Andersen’s work; however, in her later works, including the children’s book Petruskas laksko (1989; Petruska’s Patent Leather Shoes), it is given new dimensions. Anna, Petruska, and Sebastian live on the periphery of the adults’ universe where they are disruptive, insistent, strong in their unlimited demands, but also threatened, on the threshold of a condition that is fantastical, or even psychotic. The childish contains, for better or for worse, everything that is apparently foolish: desire, chaos, lawlessness, selfishness. It stands in contrast to the rules and ritualisation of the adult world, but is also a condition that is present in Vita Andersen’s adults, especially in all the anxious women. It remains a mystery how it is possible to become an adult as anything other than a thin veneer over a little child.

Anne Strandvad (born 1953), who made her debut in 1980, has in a number of novels continued the line of realistic, experience-based prose from the 1970s. Ingen kender dagen (1989; No One Knows the Day) is about the lowermost strata of Danish society in the inter-war and post-war periods, and Solbjerget (Sun Mountain), from the same year, is about the hard-working and talented young girl Line, who decides to disappear into madness to escape her deceitful family relations.

The Suffering Child

If adults were children

and the children were roses

that grew in gardens

and were watered

or tied up

when they couldn’t grow on their own

The quote is from Charlotte Strandgaard’s (born 1943) poetry collection Brændte børn (Burned Children) from 1979. Her adults, like those of Vita Andersen, are wounded children; however, in Charlotte Strandgaard’s world there is a steady insistence on reconciliation and redemption alongside the pain. The poems about the “burned children” serve to frame the larger middle section, “Hej kvindelatter” (Hi Women’s Laughter), a series of poems/hymns in tribute to women that, in line with the credo of the women’s movement, culminates in a call for solidarity, revolt, and laughter.

Charlotte Strandgaard made her debut in 1965 with the poetry collection Katalog (Catalogue), and throughout the 1960s and 70s she wrote a number of collections of poetry and documents that focused on typical problems such as alcoholism, drug addiction, social outcasts, and losers. Her universe is ruled by suffering, misunderstandings between those who want to love each other, guilt, and hopelessness. The tone (and the position) is compassionate, and there is a willingness to find an explanation and a solution. This duality becomes even more pronounced in her novels, beginning with Når vi alle bliver mødre (1981; When We All Become Mothers), about motherhood’s eternal sense of guilt, and continues in Lille menneske (1982; Little Person), about anorexia, and En fugl foruden vinger (1985; A Bird without Wings), about surrogate mothers. Each novel takes up a topical social and psychological issue, which also serves as a springboard to another, mythical level.

The mother in Når vi alle bliver mødre (1981; When We All Become Mothers) feels guilty for the death of her seventeen-year-old son, which she thinks is suicide. At the last moment, the novel’s other death-obsessed mother comes to her rescue with the knowledge that the son’s death was an accident. The common release is told in verse form, so the birth of the daughter becomes the symbol of the women’s personal rebirths as alive and powerful, a pure and guilt-free womankind as well as a tribute to the life-creating ability and the principle of life:

… and then I no longer feel longing

and then the room becomes vivid

and I understand

that the longing for life’s creation

all the eyes that follow me

are a message telling me to live

to love

to fight for a better life

for you and me and all the eyes

and I say good-bye to the

painful grey concrete.

In 1986 Charlotte Strandgaard published three books, each focusing on an individual on the fringes of society – and of life in general. The poetry collection Cellen (The Cell) is about the adult poetic speaker’s eighty-three-day journey out of depression, and in the short stories Lille dråbe (Little Drop) and Giv mig solen (Give Me the Sun), the world is viewed from the perspective of a sick child. The five-year-old girl suffering from heart disease in Lille dråbe is tempted in her dreams by death and given the task of finding no less than the secret to life and death in order to choose life.

Rather than a piece of child psychology, the work is a symbolic reworking of the battle for life as a laborious process of realisation and choice that the individual must undergo. In Lille dråbe, the sun becomes a symbol of the life-giving force. In Giv mig solen and the sequel Og alt hans væsen (1988; And All His Works), the father is the sun that shines on the daughter’s existence. The story is about an odd and gifted ten-year-old girl’s troubles at school and at home in Aarhus in the 1950s. However, its theme is again the forces of life and death, and their intermingling and interaction with an ambiguous family situation, in which the father-companion also represents a dark side of impatient urges that the girl, Inger, begins to understand only slowly and imperfectly. His light does not shine on her mother, who has given up her musical and mathematical skills to embroider chair covers.

Inger encapsulates the family’s conflicts in her life as a talented, sickly, sweet, and socially isolated girl who gets her own – independent but mad – identity when Catherine of Siena takes up residence within her and seeks to convince her to share in her renunciation of food and sleep and a normal woman’s life. The obsession threatens to lead to madness and death, but also becomes her opportunity to develop her own view of the world beyond that of her parents and society. The price for autonomy appears to be madness and death, and the first volume ends ambiguously with the white light of Catherine and madness, which is radically different from the father’s. In Og alt hans væsen it is an older brother, long dead, who speaks within Inger about a different view of their parents, which reveals their loveless relationship, their imperfection, and the constraints they place on their daughter’s life. The novels do not end in reconciliation but in the tension between social idealisation, the child’s dream about love, and the constant references to the ambiguity and secrets of adult life.

The family situation within which the suffering child lives becomes even more complex in the story about the prostitute and drug-addict Conny’s daughter who is placed into foster care. Tilfældet Heidi (1991; The Case of Heidi) involves two families and the supervising social worker in a complex plot without heroes or villains, but with the risk that everyone can get hurt by the damaged child’s destructive and constant demands for love. The hope is that the adults will finally grow up and understand their roles in relation to the child and to childishness.

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd