The five great novels by the northern Norwegian author Herbjørg Wassmo (born 1942) that came out in the 1980s and 1990s have, in all their complexity and apparent differences, one overall theme: the neglected child. The trilogy about Tora and the two novels about Dina and her son Benjamin are about children standing in the shadow of their parents’ conflicts. The child’s most fundamental needs are not met; it is neglected at a basic level where the sense of identity and ability to love is formed.

Herbjørg Wassmo made her debut as a poet in the 1970s and has since written both plays and documentary literature. In the latter genre she won an award for Veien å gå (1984; The Path to Walk), about a family’s flight during World War II.

However, Herbjørg Wassmo’s intention was apparently not to criticise inadequate or unloving parents nor to castigate an alienating society in a modern sense. The actual conflict takes place at a deeper level. In addition to telling the story of the young and unfinished person in a complicated socialisation process, “the neglected children” represent primarily the “childhood injuries” we all carry around with us – regardless of age, time, and situation.

The Tora trilogy: Huset med den blinde glassveranda, (1981; Eng. tr. The House with the Blind Glass Windows), Det stumme rommet (1983; The Mute Room), and Hudløs himmel (1986; Vulnerable Heaven).

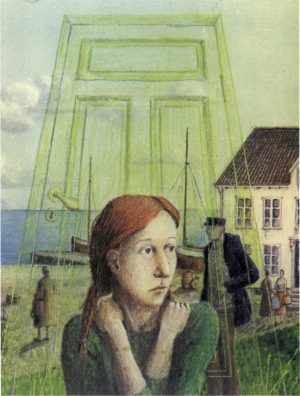

Tora: A Child of Our Time

In the Tora trilogy, 1981-1986, the incestuous deeds correspond to Tora’s hopeless social situation as the child of an occupying German soldier. Tora is clearly a victim and is well aware of it. She identifies with the cat that nobody owns and that is manhandled to death by the other kids: “It must have been the cat’s own fault. Because no one owned it and took care of it. It had been decided long ago. There was no avoiding that fact.”

In the Tora trilogy, the perspective shifts and changes between the narrator and the main character within an apparently realistic narrative. In the beginning there is a reassuring distance between the two, but this changes as Tora develops. The narrator’s language also gradually becomes more “mad”.

Tora is an outsider in all respects. The great Norwegian society that is governed from the capital is responsible, during the post-war social-democratic reconstruction period, for assaults on the little island society where Tora belongs. In that environment, she is the war-child – a bastard child with a German father – who is teased and tormented. She constantly reminds her mother of her forbidden love. Her stepfather’s sexual abuse of the “enemy’s child” is classic: the injured war veteran Henrik reclaims his manhood by violating the enemy’s (child)woman.

Tora does not blame her surroundings, and is to a certain extent loyal to her abuser. This helps create an even stronger barrier between Tora and her mother: “It was as though Tora shrank under her look. The entire room swayed slightly. […] She understood that Mamma saw them: Henrik and her. She saw herself and Henrik dissolve into nothing in her mother’s eyes.” As the chosen one she is, on top of everything else, her mother’s “rival”. When the child seeks support and identity in the adults, she is greeted with fear, rejection, and animosity.

Tora mentally attempts to “escape” her own “dirty” body, a reaction that develops into a psychotic shift in identity, and into linguistic “chaos”. Madness as both escape and revolt is a well-known theme in women’s literature. What happens to her body has no mode of expression in everyday language. The experience is a “silent knowledge” without verbalised references to reality. Tora believes that she is alone and guilty.

Psychosis as a “reasonable” escape from a “mad” world is a theme that many feminists have taken up – inspired by, among others, the British psychoanalyst R. D. Laing. Madness expressed in literature can help communicate the silent message for which there is no room in “normal” language. Many women’s experiences take place in the form of silent knowledge in the social linguistic space. The same holds true for the experiences of the neglected child.

It is interesting to note that the only possible “escape” for women seems to be an outhouse: a two-seated outdoors WC where men are not permitted. The women’s discussions, the intimacy, and the escape through reading advertising texts and old weeklies take place in peace in the place of the body’s own cleansing. Together with the trilogy’s extended use of food symbolism (note the many kitchen scenes) and the scene in which Tora soils herself as a child out of fear of interrupting Henrik’s entertaining verbal exchange with the men in the marketplace, Herbjørg Wassmo provides new points of view on different female body experiences.

The description of a special woman’s room is a solid tradition in women’s literature. Reading Virginia Woolf’s (1882-1941) A Room of One’s Own (1928) together with Marilyn French’s (1929-2009) The Women’s Room (1977) reveals how intellect, language, and the female body’s presence in reality, as well as in literary imagery, is dependent on such a sanctuary.

As the ‘neglected child’, Tora subsequently buries her own stillborn child. The text depicts many injured or dead children. Or, as in the case of the good Aunt Rakel, childlessness and intestinal cancer. The living conditions of women are presented as poor, and yet they are still capable of displaying courage and drive. The men are not accorded much honour.

Dina: The Hand and Spirit of the Law in the Framework of Death

In Dinas bok (1989; Eng. tr. Dina’s Book), the background is the child’s involuntary killing of her mother. The conflict from the Tora trilogy is apparently turned on its head. By mistake, five-year-old Dina triggers a mechanism that causes a giant vat of boiling lye to fall over, spilling its contents on her mother. Since then, the sound of Hjørdis’ painful screams and the image of her face half scalded to the bone persecute Dina as a constantly recurring nightmare.

After a “wild” upbringing, Dina is married off at the age of sixteen to the no-longer-young Jakob. But because Dina has an insatiable sexual appetite, he seeks out another, less demanding, woman. Dina discovers his betrayal and kills him. After that, Dina quickly experiences a series of changes: first, she isolates herself in the attic of the farm in complete silence, a repetition of her childhood voiceless reaction to the death of her mother and rejection by her father. Then she gives birth to her son Benjamin and gradually takes over management of the farm at Reinsnes. Dina becomes a typical mistress of the house and is described as demonic, masculinised, and secretive. A love affair with the mysterious Russian Leo is depicted as a battle between two independent souls. She does not appear to feel much for her son. His desperate search for attention leads him to witness his mother’s third murder. Leo is incorporated into her “inner circle” with the dead Hjørdis at the centre, and from which no one can escape. As a silent witness, Benjamin becomes an accomplice to patricide.

The child in Dinas bok is dynamic and mortally dangerous when given the freedom to act. The driving force is, among other things, a sense of guilt. Dina is a new version of “the neglected child”, who rejects her own offspring and “transfers” her feelings of guilt to him. Classic female and male traumas are played out in one and the same individual: incest and patricide are carried out as though they are both necessary and inevitable. Dina practices a new law.

Matricide is literally a purge, a symbolic purification of the motherly. In the “normal” social context, the action results in Dina’s father, otherwise a figure of strength – the high sheriff – losing his power and importance. Dina creates a new context with the Mother as divine and the Bible, inherited from her mother, as her new linguistic reality. The Bible’s linguistic power recurs on all levels of the novel. Herbjørg Wassmo introduces each chapter with long quotes from the Bible, and she gives most of the important characters biblical names. The text is centre-field both literally and figuratively.

Dina also uses music as a mode of expression. For her, playing the cello is a way of giving herself over completely to her emotions, a semi-physical precursor to verbal communication. Music contains the possibility of understanding without words. However, Dina’s actual artistic dreams are not fully expressed until Lykkens sønn (1992; The Son of Happiness; Eng. tr. Dina’s Son). The musical instrument ultimately serves as a link between mother and son, and the sequel is about Benjamin’s search.

In Charlotte Brontë’s (1816-1855) Jane Eyre (1847), a cornerstone of women’s literature, the madwoman in the attic is depicted as a combination of ghost and castrating woman. In her novel Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), Jean Rhys (1890-1979) gives the “madwoman” a new life. Not only is the room opened up, the woman’s path up to the room is also described. Herbjørg Wassmo opens the room as well, describing the path to it and making the room the “centre of the world” – a place for everything from free and full-blooded sex to solutions to legal disputes. The choice of the historical yet modern novel form allows the exuberance and otherness of the Dina character to be played out for all of society to see.

Benjamin: See Me, Love Me

Lykkens sønn is a direct sequel to Dinas bok and has the same structure: the prologues highlight problems associated with life and death, break up the chronology, and clarify the theme relating to the “neglected child”. The plot in Lykkens sønn begins with the “original event”, the murder of Leo, which marks Benjamin for life, giving him fearful fantasies about loss and pain, sickness and destroyed bodies. Like other victimised children, Benjamin suffers from overwhelming guilt and can find no refuge in sharing his reactions with his mother. In this lies a parallel between mother and son. However, this time the perspective is that of a man.

In Benjamin’s universe both his own painful life and the suffering of the entire world lead back to the murder: “Within the Circle, I stand. And the man. He lays there in the heath with his head covered in red froth. It spreads out further and further. The red is the circle around us. Around him and me. While she steps backwards out of everything. We cannot reach her. […] Then I feel her hands on me. They touch my head. […] She digs her fingers into my eyes. Slowly. Until everything turns black. […] I recognise the smell from her fingers […] but I can’t see her because she has stuck her fingers into my eyes once and for all.”

Benjamin loves and fears his mother and he searches for her for the duration of the novel. In Lykkens sønn Dina has changed. She leaves Reinsnes with her cello and moves to an unknown location in Germany. But her artistic dreams are not fulfilled: she is too untrained. On the outside, the strong, dominant woman has disappeared, replaced instead by an almost tragic figure. However, she retains for a long time her demonic role as the source of fear and longing in Benjamin’s mental life.

The boy also has an intense longing for a father. In a sense he has three: officially, there is the dead Jakob, biologically the stable boy Tomas, and as a loving mentor the loyal Anders, whom Dina surprisingly marries before leaving Reinsnes. And yet he still feels as though Dina has prevented him from having a father. He does not learn the truth about his real father until mother and son meet in Copenhagen. And this knowledge is immediately used to identify and accept his own motherless daughter.

All of Benjamin’s sexual experiences seem to involve blood, violence, and dejection. For the son of happiness, love represents danger and the threat of annihilation, as does Dina herself. The mental fragmentation involves an abyss between body and emotions, and in this he resembles Tora in a way. However, Benjamin swings back and forth between two types of woman – the “whore” Karna and the “Madonna” Anna – who represent two sides of Dina herself, erotic and reflective respectively.

Studying medicine gives him a concrete and scientific relationship to bodies. Mutilated and bleeding bodies. Perhaps Benjamin the doctor seeks the battlefield as penance for Leo’s bleeding corpse? The tendency towards philosophical and religious speculation stands in stark contrast to all the physical grotesqueness. Yet in contrast to Dina, who studies and interprets the words of the Bible directly, Benjamin takes his own usual detours. His inner chaos is expressed with the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard as determining “interlocutor”. Benjamin is searching for the meaning of life – which is actually about understanding his parents’ neglect – through, among other things, questions about the father of all fathers: how was Abraham capable of sacrificing his son Isaac? What about loyalty to his child, what about the child’s perspective? The sins of the fathers are just as serious as the weaknesses of the mothers.

Lykkens sønn has a relatively open ending with no new calamities other than Dina repeating her erotic adventures – this time with Benjamin’s best friend. Compared to the Tora trilogy and Dinas bok, this is practically a happy ending. However, it is thought-provoking that the hope of a better life lies in the father’s acceptance of, and sense of responsibility for, his child. It appears as though Herbjørg Wassmo is saying that love and happiness must be based on a redefinition of the male role.

In Norway, (male) academia is very sceptical about the work of Herbjørg Wassmo, as is clearly expressed in a relatively recent one-volume history of Norwegian literature, Norsk litteratur i tusen år (1994; A Thousand Years of Norwegian Literature), which claims that the writing style in the Tora trilogy is “traditional and not particularly problematising” and that many (but who?) consider Dinas bok (Eng. tr. Dina’s Book) nothing more than pulp fiction.

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd