A selection of Suzanne Brøgger’s (born 1944) freelance journalism texts from the mid-1960s has been reprinted in the anthology Brøg 1965-1980, which provides a good idea of the young writer’s interest in foreign policy hot spots, her affinity for personalities in existential outsider positions, and her never-failing sense of the provocative. Her debut book Fri os fra kærligheden (1973; Eng. tr. Deliver Us From Love) and the subsequent Kærlighedens veje og vildveje (1975; Love’s Highways and Byways) carry on the 1960s journalism in a mixture of fiction, memoir, erotic fancy, and personal experience. Her debut book is especially famed for its brilliant analysis of the psychology of rape that is woven into the story of her own rape by a group of soldiers in the Soviet Union. It is a lesson in the logic of oppression, conveyed by a baroque and grotesque humour.

Kærlighedens veje og vildveje includes an article simply called “Nej” (No). It is the woman’s NO advocated by the young Suzanne Brøgger because the “greatest declaration of love women can make today is a NO to the terms”. And she does just that in her first two books, in which she says no to the great, individualist love, to marriage, to the nuclear family, and to children – since the Western world no longer has a need for its children – to the prohibition of incest because it is the “mainstay of the patriarchy”, and, finally, to her aversion of preference, marital monogamy, which women “are abandoned to”.

“Not everyone is in a position to abolish capitalism. But anyone has the right and the option to abolish the nuclear family,” so why do feminists not put the dissolution of the family on the agenda, asks Suzanne Brøgger. And her own answer is that “as a rule, women would rather have a husband than a life,” that it is women’s fear of a loveless life which keeps them from exploring their untried options. However, many things would be different if only women would realise their erotic potential, “which simply means having a direct relationship with the world,” writes Suzanne Brøgger. But the problem is that women are, on the one hand, “emotionally encoded to a programme that has run its course” and, on the other hand, “cut off from falling back on history without having to pay for it with their intelligence”. Consequently, women’s path to a new identity passes through a void. Women can do whatever they want, and the women’s movement, in Suzanne Brøgger’s opinion, is not about liberation but rather “the fear of floating freely in empty space”.

In a Swedish debut novel, Mun mot mun (1988; Mouth to Mouth), by thirty-year-old Nina Lekander, Suzanne Brøgger’s early debate books are referred to as battle texts canonised by an ever smaller, but no less brave, flock who have not given up despite the deathblow when Suzanne Brøgger’s late pregnancy was announced. To Nina Lekander, she is a deserter who still deserves to be honoured for her early efforts and insights.

With the fifteen-year-old Suzanne’s erotic initiation on black silk sheets in Bangkok, the foundation is laid for the NO, which introduces her body of work. In Creme fraiche (1978) she tells the story of how she experiences “with her own body” the fact that “most men cheat on their wives”. She gets to know the “tears, guilt, and disappointment” of the cheated through “the intimacy of the men”, and the idea that she could one day end up in their shoes terrifies her. “It was such a threat to my ego, ideals, and aspirations that I had to find another way to live, whatever the cost”. She therefore invents her own insurance against sexual deception. “Because when you wanted beautiful women for your lovers, you couldn’t be cheated on.” Now, no one could cheat on me, she writes. In Bangkok, thirty-year-old Max was her mentor, in Creme fraiche it is Henry Miller, whose spiritual daughter she declares herself to be. However, the objective in Creme fraiche is to remain a daughter and a child. To avoid, at any price, becoming a woman and an adult.

Women’s happiness threshold in marriage, according to Suzanne Brøgger, can only be defined in negative terms and on a progressively diminishing scale:

“‘I’m happy as long as he doesn’t cheat on me.’

‘I’m happy as long as I don’t know about it.’

‘I’m happy as long as he doesn’t leave me.’

‘I’m happy as long as he comes home for meals.’

‘I’m happy as long as he comes home now and then and doesn’t make a scene.’

‘I’m happy as long as he doesn’t beat me.’

As long as he doesn’t stick a knife in my eye, well, as long as he doesn’t twist it, life is still worth living.”

Fri os fra kærligheden (1973; Eng. tr. Deliver Us From Love).

If the cheated wives are something to be frightened of, then the relationship to the mother of her childhood is different. In Creme fraiche it becomes apparent that the distorted woman’s portrait in “Kvindetrip” (Woman’s Trip) in Fri os fra kærligheden is based on Suzanne Brøgger’s own mother. Only one thing is worse than an oppressed woman, writes Suzanne Brøgger, and that is a woman who has stopped being oppressed. The mother’s suicide attempt and the perpetual staged illnesses are part of daily life, and as an adult she constantly hears her “sobbing in the back of my mind, her crying follows me everywhere”, a story that is pursued in the autobiographical essay “Febricitanten” (The Febricitant) in Kvælstof (1990; Suffocation).

Ja (1984; Yes) is a further expansion on the story of the stepfather. The object of her stepfather’s desires and a guardian to her mother, Suzanne Brøgger refused to change places in the Oedipal triangle. She remained “in the ambiguous position of half daughter, half wife, both and neither” and she wonders whether she “shares this vague position with women of her generation, who in their youth formed movement. Did they, too, occupy the place of indignation in the triangle? Did they refuse to budge even an inch?” Is the women’s movement of the 1970s a daughters’ movement borne by a NO to assuming the place of the woman, the mother, asks Suzanne Brøgger in Ja.

In Brøgger’s fiction, Creme fraiche is written on a flight from New York to Copenhagen. With great reluctance, the narrator leaves the USA, and would prefer to stay in the air in deep harmony with the book’s philosophy “that the surface has everything, there is nothing underneath, nothing but pure fancy”. The world is a playground and life is a playful challenge for the narrator, who is driven by “a powerful desire for freedom teasingly accompanied by the absolute opposite”. She considers herself a survivor of the 60s revolt, a terrorist whose weapon is her sex. With an unambiguously professed allegiance to May 68 and the revolutionary philosophy, Creme fraiche becomes part of the youth revolt’s optimistic project when Brøgger finally writes that we “from the golden horde to the tribe, from the tribe to the extended family, from the extended family to the nuclear family, and from the nuclear family have finally deduced our way to the disconnected individual”. All that is left is the individual, a collection of excited, vibrating atoms.

If anyone believes they have seen through the fear in the invocation of femininity, Suzanne Brøgger is more than willing to admit she is frightened. “Because I’m not a cow,” she writes in Creme fraiche. The fearless, on the other hand, she considers to be cows “who file past on their way to the scaffold, proud of their courage. She is frightened, they howl from behind their blindfolds. She is afraid to be butchered like the rest of us”.

Tone

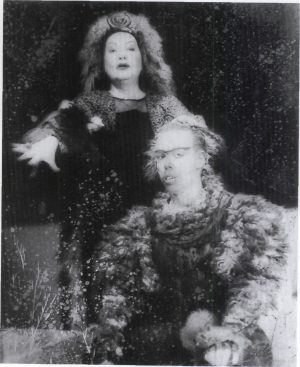

En gris der har været oppe at slås kan man ikke stege (1979; You Can’t Roast a Pig that Has Been in a Fight) deflates the illusions of the ‘first-person narrator’ in Creme fraiche, telling instead the tale of the lonely life of an author out in the country, far from the temptations of city life. Two years later, in a Zen Buddhist-like submission to the now, the landscape, the neighbours, and the changing seasons, Suzanne Brøgger catches everyone off guard with the character poem Tone (1981), changing her style completely. This epic poem about the milliner and life artist Tone relates in a cheerful and quick-witted manner “a woman’s chant for anyone in need in hard times”. Suzanne Brøgger paints a heroic portrait of a Renaissance woman, an idealised mother figure, an all-embracing woman from whom love flows unhindered towards everyone and everything. Tone comprises all the notions of a female Eros, of a female desire. However, this supreme generosity, this impassioned giving of the self, is accompanied by a demonic power, which is the constant shadow of lust in Suzanne Brøgger’s erotic universe. Tone’s life, which starts with a traditional marriage, husband, and children, becomes filled, after the husband’s constant treachery and a tough divorce, with a huge NO. She continues to give everything she has, but she no longer accepts more than she can stand to lose again. This reversal of a victim-contract with life, as presented by Suzanne Brøgger, is intriguingly heroic and idealised. But the pain, Tone’s death by cancer, and a wedding at her deathbed are proof that in Tone, Suzanne Brøgger has reached the limit where fear can no longer be conjured away. The reversal and the breakthrough are given free rein in the novel Ja from 1984.

Ja

“What would happen if you changed places in the triangle and took over the woman’s place, in other words, if you gave in?” the main character asks herself in Ja, thereby turning the problem from the previous books on its head. Now, it is no longer a matter of being your own stage manager, but of being open to a fate that has been written beforehand. Now, it is no longer about quieting the demonic weakness, but instead asking the demons to dance in order to become yourself.

At the centre of events is the female main character we meet in Creme fraiche and her beloved, a Swedish obstetrician. Around them is a circle of supporting characters who have all split off from the main characters. Thus, Luna is the woman whom the main character no longer wants to be, Hilda is the woman she is afraid of becoming, and finally, Yoshi is the harbinger of death to whom she longs to say both yes and no. Luna represents an internal battle with the promiscuous main character who “absolutely must have sexual contact with men. Not for pleasure, but to dampen a deep-seated restlessness”. The psychotic Hilda is the woman into whom the love story threatens to transform her and, finally, the friend, Yoshi, is driven by a desperate self-destructive need that symbolises both the obstetrician and the main character herself, or more specifically, the passion that again and again drives them into each others’ arms.

Basically Ja is a classic story of redemption. The passionate alliance does not lead to a legal marriage, but rather to the female main character’s death, funeral, and resurrection on the third day, and thus to a new story of passion, a heavenly ecstasy culminating in an orgasm in free fall from the Mount of Olives in Palestine. This establishes yet again the flying dream and the fantasy of omnipotence, which recur in various forms throughout Suzanne Brøgger’s work, with the entire story growing out of the wing she gets tattooed on her heel in the beginning of the book. Thus, Ja turns out to be an artist’s novel in which the female artist is resurrected from the burial chamber of femininity. Suzanne Brøgger’s transition from NO in 1973 to her YES in 1984 is basically about a personal journey to an authorship, an artistic way of life.

Femininity is put to the test in Ja, but always with the writing stretched out as a safety net. An existential analysis of the state of fear which, in the name of submission and conjuration respectively, produces material for a woman artist’s book machine.

As early as in the article “Forførelse og hengivelse” (Seduction and Submission) in Brøg (1980), Suzanne Brøgger writes that “Eros became wingless when he was set free”. Now, eroticism is the realm of the therapist, and it “flourishes today on a part with Valium and other dulling substances”. From being a question of whether two people in love can sleep together without being married, the answer has become that you MUST sleep with SOMEONE, even if you love no one. That is why today’s law speaks the language of freedom and it is no longer the orgasm that gives wings. If you want to fly, other means are necessary. A clue to this other can be found in Den pebrede susen (1986; The Costly Whisper), about being in connection with the cosmos, the creative forces of the universe.

“In the past, the patriarchate spoke Greek or Latin, while the women always spoke in vomit and blood that flowed back to heal the body of society,” writes Suzanne Brøgger in a very concise description of the literary history of the sexes. Den pebrede susen (1986; The Costly Whisper).

The climax of the book is an essay called “Den hellige anorexi” (The Sacred Anorexia), its impasse is a series of lamentations on the price of fame. The readers have confused Suzanne Brøgger with the Suzanne Brøgger she wrote about in her books. And that was never the intention! Suzanne Brøgger considers the price of fame again in Transparence (1993; Transparency), part three in the series after Creme fraiche and Ja: “The attentive reader may have followed the phenomenon as it flew through the dark writing on a little pad and since witnessed existence as an imploded star, a creature of nothingness with – difficult as it may be to believe – a wing on the heel. But it gets even worse before the reader can finally find peace”.

Throughout the story about Emmanuelle Olsen, the ‘I’ character’s doppelganger, Suzanne Brøgger tells about the daily stalking by mad people who think they are the author and who act in her name, resulting in innumerable embarrassing misunderstandings. But both Emmanuelle Olsen and Ben, her piano teacher, are identified as barely concealed projections for a half-hearted self-rebellion. A child is introduced in the story as a sign of a forthcoming change. “Children were the only people who were not afraid of the seriousness of existence. With a child it was possible to stare constantly into the mystery”, and the story ends on a life-confirming note with the pen pal, Z, showing up with “giblets for the cat, a salted herring for me and a saw and an axe” to be used to cut down the forest of briars. Sleeping Beauty is apparently to be awakened, and once the briars are conquered, the tormenter and doppelganger, Emmanuelle Olsen, also disappears.

An authorship, a husband, and a child’s visit mark the end for the time being of the serial princess’ fantastic tale. We leave the main character just as she is about to live out her YES to love and femininity, and Suzanne Brøgger herself also tells an unmistakable tale about the dark side of revolt and the consequences of NO in her essays (Kvælstof) as well as on the stage with two noteworthy pieces for the theatre, Efter orgiet (1992; After the Orgy) and Dark (1995).

“At the time, it caused an outcry when sexuality – in connection with the youth revolt twenty years ago – was expanded to include much more than the actual acts of intercourse and reproduction in technical terms. For it also came to be about power relationships, gender roles, values, and identity formation; in short, the entire structure of the Western world. To put AIDS into a similar context of social-criticism evoked just as much resistance back then, and I am trying, based on my own doubts, to find out why,” writes Suzanne Brøgger in “Virus 2” in defence of her use of AIDS as a metaphor. Kvælstof (1990; Suffocation)

Efter orgiet, in which the characters Organ, Rigor, Vulva, and Mortis perform an incestuous, Oedipal death dance in a Brøggerean version of the Greek tragedy’s rhetoric, sparked the same shock and dismay as twenty years ago when Suzanne Brøgger wanted to free us from love. This time, it is desire that is sick, and with a prologue by the moon goddess Hecate, she cuts to the bone. “Infection has replaced procreation,” proclaims Hecate, and in the play AIDS becomes a fateful metaphor for the dissolution that was the result of the women’s NO. The NO to the terms of motherhood is now presented as the “time when women grew up as men, and sons became women,” the “time when women were alone and men were thrown out after violating their daughters,” and finally the “time when sons had to arm and protect themselves in order not to succumb to the lust of the lonely mothers”. Efter orgiet is a distorted image, a nightmare, and a perverted catalogue of modern relations, a merciless diagnosis of a culture of destruction. In the tragedy Dark, it is the loss of femininity that is played out in a modern Joan of Arc story about a woman who has lived like a man and who enjoyed it while it lasted. About a child who was not allowed to be a child and who therefore never grew up, a story about a woman whose loss became too great. With her new version of the Old Norse poem Vølvens spådom (1994; Prophecy of the Völva), Suzanne Brøgger throws her modern images of destruction into sharp relief. “Would I be capable of finding a way into ‘the planet’s workshop’, into the place which is the source of the prophecy of Ragnarök,and from which the words pour forth?” she asks herself in the afterword. The beautiful reinterpretation of Vølvens spådom demonstrates that both Greek tragedy and Nordic prehistory fit perfectly in a body of work that continues to develop promisingly and unpredictably.

Translated by Jenifer Lloyd