War casts long shadows across post-1945 Norwegian literature, and the work of Gunvor Hofmo (1921-1995) should be read from the perspective of a broken reality. At the same time, however, this approach might overlook important aspects of her writing; aspects that become clearer when we fast-forward a generation and read her twenty poetry collections as a whole. Gunvor Hofmo’s poetry is not based purely on the experience of war and post-war; it deals just as much with human conflicts linked to body and gender.

The child and childhood are a key motif in Jeg vil hjem til menneskene (1946; I Want to Go Home to Humankind). “Through empty streets roams / a child who has gone blind / who touches your window, / so softly and so gently.” The penultimate stanza reads: “The abyss behind images / and bottomless tenderness/ loneliness like flames / without voice, without mouth.” The child is portrayed as a small human being who cannot see, cannot speak, and does not have a mouth.

The childhood depicted in Jeg vil hjem til menneskene is associated with red blood and wounds that can never heal. The child has been rendered blind, bitter, mute, and lonely. The helpless and forsaken child is a recurrent motif, with variation of scene, throughout the oeuvre: the child standing outside the door, knocking to come in; the child standing outside on a cold winter’s day, looking up at a window; the homeless child wandering the empty streets.

The events of childhood, on which Gunvor Hofmo’s post-war poems constantly turn, have always been interpreted as a general construal of violence inflicted by war on the individual. There is, however, so strong an element of wound metaphor and use of words such as shame, uncleanliness, and degradation, that this interpretation overlooks an equally fundamental aspect of her texts: the ill-treated child. Her first five collections – before she took a sixteen-year break – manifest a deep dissonance contending both with war and with the human body.

Gunvor Hofmo’s debut, Jeg vil hjem til menneskene (1946; I Want to Go Home to Humankind), and the collections of poems that followed – Fra en annen virkelighet (1948; From Another Reality), Blinde nattergaler (1951; Blind Nightingales), I en våkenatt (1954; In a Waking Night), and Testamente til en evighet, (1955; Testament to an Eternity) – have been read as her reaction to the horrors of World War Two. In addition, her close relationship with Ruth Maier, a Jewish woman who was murdered in Auschwitz in 1942 at the age of twenty-two, has been cited as the personal experience that motivated her war theme.

The Knife: The Intimate Man

The blind child is a recurrent motif in Gunvor Hofmo’s work, elaborated in detail in the collection Blinde nattergaler (1951; Blind Nightingales). The opening and title poem is an elegy to nightingales, who have had their eyes gouged out and must thus forever sing about the pain. The motif of ‘being blinded’ is presented in a number of variations: “the scream of the eye / on the blade of the knife”, “something blazes through the wall of the darkness”, “the cruel, raw flash”, “poked out those deep dreamer’s eyes”, “You, God, are the one who has / poked out our eye”.

Men do the blinding, and men are the players in war, but which war? Jeg vil hjem til menneskene has but few actual war poems. The masculine element is primarily rendered in cold abstractions. In later poems, the aggressive male is conveyed by means of various characters suggesting that in this picture of reality, war is just as much about an adult’s outrage committed against a child or one gender’s assault upon another. A stanza from the poem “Jeg har våket” (I Have Kept Vigil) from I en våkenatt (1954; In a Waking Night):

I saw my father in the room,

wise, but unfeeling too.

And behind him

a surge

of men with weapons raised,

murderers, but battle-scarred themselves.

In “Et drømt brev” (A Letter Dreamt) from I en våkenatt (1954; In a Waking Night) we read:

“How long are you a child waiting in streets at dusk for a window to open? How long can you stand staring at this lighted window? In time you retreat into the corner, into the shadows where greedy hands await, where sleazy lips smile in satisfied conviction, and when you leave there, you want to wash yourself, but with what?”

Frost: the Distant Man

“Vinterkveld” (Winter’s Evening), the opening poem in Gunvor Hofmo’s first collection, is a chilly portal into her written universe. The first stanza reads:

The crisp clear winter evening skies

they chill the heart as does a cruel friend

who sucks out your last shred of warmth

giving icy uncertainty in return.

The motif is the winter evening, which is compared to “a cruel friend” – attractive, but also intimidating. The poem goes on to describe this cruel winter, assigned the pronouns he and his: “the chill rises in his gaze”.

In contrast to the he, a lyrical you starts out as warm, but becomes colder as attempts at intimacy and contact are rejected. The condition of this you is characterised by the words pain, uncertainty, frantically seeking, voiceless, helpless. In the final two stanzas, the winter evening motif is turned into a reflection of the frame of mind pertaining to this you, and the distance, the coldness, the unfulfilled dreams, and the abortive communication become the image of human aloneness.

The poem is typical of the modernist sense of alienation and the chasm between individual and reality. Here, the split is rendered more specific by the use of a you and a he. He is a “cruel friend”, a masculine principle, awakening both desire and pain, but mainly coldness and the sense of aloneness.

But lured by deeper eyes, you abandoned yourself to sorrow. Too late you fathomed his purpose, too late your ardour chilled.

Gunvor Hofmo’s early poems project the masculine element either as aggressive and intimidating in its intimacy or as an abstract absence that gives rise to a feeling of emptiness and need.

Desire and War Metaphors

As a theme, desire chimes intense dissonance in Gunvor Hofmo’s early works. The cold front of the opening poem in Jeg vil hjem til menneskene houses a sensual and passionate desire, but this is turned inwards in self-destruction just as much as it is directed outwards towards another individual. The poem “Forventning” (Expectation) is perhaps the best example of a text in which the ambivalence of sexual desire is put on the agenda:

Your manner is all ablaze

and behind it I tenderly see,

a frenzy of expectation

which threatens and entreats!

O deep deep certainty:

did you once exist?

Everything is buried

in this fiery hunger.

Yes, between me and the world

lies a burnéd bridge

for my soul has been consumed

by the fire in my blood!

The use of metaphor in this poem draws on the ravages and horror of war: ablaze, threatens, burnt bridges, hunger, fire, consumed. But the theme of the poem is not one of war – it is one of intense passion.

In the final stanza, passion is the source of the poetic speaker being isolated from the world and it also causes the split and destruction of the “I” itself: the soul is wrecked by the “blood”. Should this be read as sensation getting the better of sense? Or might it be expressing fear of a destructive desire? The expressionist imagery would seem to indicate the latter. The horrors of war become an image of the inner disintegration of the “I”. Read in this way, the use of war metaphor becomes a language. A language that is intense enough to reflect fear, passion, and desperation.

Sexual desire also seems utterly devastated; all that is left is want and emptiness and a self-destructive wish for the body to disappear. When desire is not satisfied, and the individual feels want and emptiness, a part of life’s meaning also disappears. The poem “I en mørk natt” (On a Dark Night) can be interpreted in this way. The opening lines read: “I love nobody, / you starless night, / I love nobody.” In the final stanza, not only does the first-person voice express longing for death, it also pleads for an agonising end:

Come then vultures!

Swoop with piercing shrieks

through rain and storm

and rip me to shreds, a corpse,

and abandon me to the worms

and leave me there to lie:

A wretch, cut off from life!

Gunvor Hofmo’s first five collections play out a dramatic battle between child and adult, woman and man, faith in life and longing for death. While the ‘children poems’ and ‘coldness poems’ express a high degree of fear linked to the male element, the ‘desire poems’ involve fear that desire will have a destructive effect on identity, that the body will devour the intellect, and thus a wish for the body to disappear.

Violent Language

Hofmo’s imagery is, at times, highly expressive and leaves an impression that only the very strongest of words can express the feeling that underlies the text. The contrast between the child’s tragic silence and the poet’s loud language is enormous.

In a Norwegian context, the same phenomenon is found in the work of, for example, Inger Hagerup, and even though it can be called an expressionist convention, the violent language can also be interpreted as a response to the violence writers observe in the world around them. Polarisation and pain cannot, they feel, be given strong enough articulation. In addition, the violent language might be a strategy to be heard at all.

The Child’s Perspective

The child as victim of meaningless violence is a fundamental theme for Gunvor Hofmo. The aspect of violence is toned down in her later poetry collections, where the child’s perspective is even more firmly upheld. The poetic subject usually identifies herself with an innocent and vulnerable child seeking care.

The foetus in the womb and the infant at the breast are both frequent motifs and poetic images used to characterise nature and universe, as in “Jeg ligger” (I Am Lying Down) from Nabot (1987):

In the maternal arms of the cosmos

I am cradled

and suckle rock and water

Oral images – drinking, breastfeeding – are recurrent in the later collections, employed as figurative language for need and want. Sexual desire thus seems to have moved gradually from an adult and female perspective to an infantile perspective. At the same time, new features are identified in the picture of God: the almighty, frightening, masculine father is now also a solicitous mother.

Cradle me, God, in your

loving

arms ’til the walls of fear crumble

and I am born again

in your spirit […]

“Vuggesang”, Nabot (1987; Lullaby from the collection Nabot).

Dimensions in the texts change, too. They become more extreme. The child becomes smaller and smaller: the foetus in the womb and the infant at the breast take the place of the child wandering the streets. The forum expands: the universe and cosmos take the place of the winter evening and the battlefield. In the course of her writing career, the violence, accusation, and polarisation of Gunvor Hofmo’s first collections is toned down and replaced by a more passive sorrow, by suffering and powerlessness. The poetic voice is more helpless and exposed than ever.

Gunvor Hofmo’s first poems keep within a more or less fixed metrical composition. The approach to the meter is, however, rather unregimented; in a number of places the meter is broken, chiefly by highlighting words with stressed syllables, where there should actually have been an unstressed syllable. This contributes to the forceful tone of the poems, and the many exclamation marks add to this impression.

A Barren Universe

Gunvor Hofmo’s figurative language is often linked to reproduction and birth: words such as fecundate, ripen, fruits, creation, seed, giving birth. But it is not the woman who gives birth, and the progeny is not a living being. Abstracts give birth, and the progeny is spirit, intellect, or aloneness: “Giving birth, / the day subsides into / the midwife arms of night” (from Stjernene og barndommen, 1986; The Stars and Childhood). The imagery is attached to a female identity and body, but it is subject to a more important authority and mission: poetry’s search for knowledge and meaning – or God. This is a poetry stretched between body and soul.

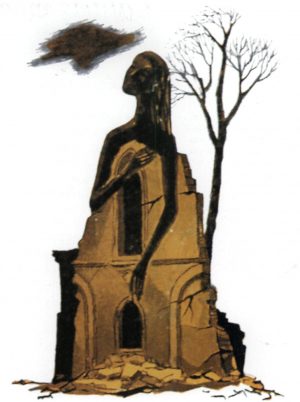

Gunvor Hofmo’s literary output projects a polarised and dissonant world picture in which the child and the woman are under the man, and the poet is under God. “There is a shadow / upon the world / vast as from / the tree of God”, says Gunvor Hofmo. Yes, and this shadow was there before the Second World War, it was already there in childhood, and it has been there ever since.

The world is not the only thing to be laid in ruins in Gunvor Hofmo’s writings – the body is too. Her first five collections not only presented the suffering, but also the passion. The next fifteen not only show the sacrifice of the body, but also the poetry of the soul. From the pain of the body there rises a voice of poetry. This dialectical tension between soul and body is the essence of Gunvor Hofmo’s poetry.

There is a shadow

upon the world

vast as from

the tree of God

where the stars are leaves

that rustle bathed

in light

and cool is the darkness

where thoughts ripen

like fruits

on the star tree.

“Det finnes (Natt)”, Stjernene og barndommen (1986; There Is (Night), from the collection The Stars and Childhood)

Translated by Gaye Kynoch