Hulda Garborg (1862-1934) wrote a lot, alternating between articles for journals, novels, and various theatre genres – comedy, tragedy, and more expressionist, experimental plays with mythical motifs. She concentrated particularly on the theatre, and much of her work was written in connection with the nynorsk movement. In the 1880s and 1890s, nynorsk received increased impetus given that, among other factors, a number of the best Norwegian writers were using nynorsk in their work. A broad movement saw the light of day, and Hulda Garborg was one of its prominent figures. Here she found her role as female arts worker.

1853 saw the launch of the first printed offensive in the battle to give Norwegians a written language to replace the use of Danish: Ivar Aasen’s Prøver af Landsmaalet i Norge (Specimens of the Norwegian National Language). Rather than approximate the Danish to spoken Norwegian, Aasen wanted to create a completely new language based in the various dialects spoken in the different districts of the country. The language conflict has remained a factor of public debate in Norway ever since, even though by around the turn of the nineteenth to twentieth century it had already resulted in two languages running alongside one another: riksmål (national language), later bokmål (literally: book language), and landsmål (countrywide language), later nynorsk (literally: New Norwegian).

From 1910 until 1912, Hulda Garborg was the leader of a touring theatre company, Det Norske Spellaget, which travelled along the Norwegian coast from Christiania to Tromsø. The first tour avoided the big towns; the company wanted to become as professional as possible before performing in front of an audience that was expected to be critical of their cultural and language policy. They wanted to counter any criticism with artistic quality.

The rural population gave the theatre company a good reception, which in turn gave Hulda Garborg the courage to put an old idea into action: she wanted to set up a permanent stage in Christiania for nynorsk drama. The city’s theatres were not particularly willing to put on plays written in nynorsk, and her projected company would also be a touring theatre – to rural districts and provincial towns. She invited subscription for shares in the company, and public authorities, private individuals, and organisations all supported her initiative. The very next year saw Det Norske Teatret (The Norwegian Theatre) become a reality, albeit only in rented premises. Its first official performance took place in Kristiansand; Ivar Aasen’s Ervingen (1855; The Heir) and Hulda Garborg’s Rationelt Fjøsstell (1896; Rational Farming) were in the repertoire. These two plays were already acknowledged classics in the nynorsk movement, they were in the repertoire of many companies, and were often put on by amateur dramatic societies in town and countryside alike.

The nynorsk movement campaigned on behalf of a minority language. Even though over ninety percent of the people in Norway spoke dialects closely akin to the new written language, only a small number wrote it. Those with the greatest political and economical influence used Danish-Norwegian (riksmål), and thus it was this written language that garnered most prestige. Hulda Garborg wanted to break this hegemony. When the theatre audience in the capital city heard good Norwegian spoken in a context that gave positive associations, she anticipated that resistance to the Norwegian language would lessen. And young people living in the rural areas would have greater faith in themselves once they could use a language that was their own.

The first performance in the capital city was arranged with great festivity, a high-flown opening prologue, and the King in attendance. But yobs from Christiania’s ‘posh’ west neighbourhood soon provided a different kind of festive mood in Bøndernes Hus (traditionally the farmers’ social centre), where the theatre was performing. A number of the first performances were halted by brawls, and newspaper articles reported that the place was strewn with blood and eggs. The conservative Ekstrabladet, which supported the disturbances, was worried about “all this oafish peasant-‘culture’ which forces itself on people with every one of its goods and chattels – its Stone Age breeding and its empty skulls painted with floral patterns.” Hulda Garborg could not walk the streets in safety.

Hulda Garborg was expected to take on the duty as leader of the new theatre, but she declined to do so. Such an important position called for a man, she claimed in her diary – with a certain degree of irony. She had been both originator and primus motor behind setting up the theatre, and she was aware of her own ability, both as play director and organiser. But she felt she had more important things to do than taking on managerial posts, and she therefore handed over the job to a respected actor: Rasmus Rasmussen. She sat on the board for many years, and she also occasionally directed shows. But the theatre needed nynorske plays to put on, and what she really wanted to be was a writer.

Women had already joined the amateur dramatics movement before the turn of the nineteenth to twentieth century. Theatre had long been seen as an acceptable pastime for country women: the theatre stage and the women’s societies became their public forum. A few women also made a name for themselves as playwrights, but most of them only wrote two to three plays each. The names of 160 playwrights account for the 300 registered dramas written in nynorsk and published before 1960 (there were undoubtedly just as many unpublished scripts). Of these writers, fourteen are women – at eight percent of the total, that is far from impressive, but at least there were women who took up the pen and, what is more, in a milieu that often treated such women as deviants.

Love and Realism

In her first nynorske plays, Hulda Garborg wrote about women’s lives in narrow-minded rural communities. Both Mødre (1895; Mothers) and Sovande Sorg (1900; Dormant Sorrow) are tragedies with single mothers at the centre of the conflicts.

Crises in the storylines are in part connected to disappointments in love and imprudent decisions of the past, which cast dark shadows over guilty and innocent alike. In Mødre, forty-year-old Lina kills her mother-in-law – and goes insane. Her psychotic fantasies are staged by means of dividing the space into three areas and varying the lighting to represent a mind split between past, present, and future. The playwright moves away from a realistic tradition of illusion and towards a symbolic form of theatre.

It is not the female lead who meets a tragic end in Sovande Sorg. Berit Moan’s bitter mind finds equanimity in the last act of the play through reconciliation with those who have caused her distress. But the man who abandoned her in her youth, and went on to marry into the family on the neighbouring estate, meets an abrupt death. Their children, Tordis and Per, unaware that they are half-brother and half-sister, defy the neighbour conflict and local gossip and embark on a love affair. But the truth comes to light, and Per leaves the village for ever.

Mødre was put on at Christiania Theater just after the play text had been published in book form, whereas Sovande Sorg was rejected, even though it had won first prize in an amateur theatre competition. The production of Mødre was not a hit. The second performance was for season-ticket holders, this being a specially ‘fine’ audience with the Swedish-Norwegian King Oskar II in attendance. On either side of the centre aisle sat “breeds” who did not understand one another, wrote the Christiania newspaper Dagbladet. “The ‘fine folk’ sat with a well-nourished contempt for this hate-fuelled battle over food.”

It was the first time the cultural elite of the capital city had experienced nynorsk used to address such a critical and realistic issue. On stage, nynorsk and dialect had previously been used almost exclusively to caricature people from the lower social classes or to heroise countryfolk, the latter being the case in national-romantic literature with its fondness for peasant tales.

The production of her comedy Rationelt Fjøsstell, on the other hand, was a success. The play was performed a grand total of seventy-seven times, and theatres in Bergen and Trondhjem immediately included it in their repertoires. The bourgeois city audience clearly found the humour and irony of the comedy less distasteful, even though this play also has a distinctly critical slant. Mother and daughter are on opposing sides in a conflict that is basically concerned with industrialisation of agricultural methods and the ideological upheavals that came in its wake. Farmer’s daughter Inger has recently returned home from a winter spent at college where she has learnt about many subjects: nutrition, new methods of cultivation – and rational cow husbandry. The college has also made her aware of women’s oppressed status.

But her ideas are not well-received. She tries to ally herself with the widely-read urbanite Jens Pedersen, who is a clerk for the local lord of the manor, and who writes poems published in the newspaper Nutidsposten. He is the only character in the play who speaks phonetic Danish-Norwegian. This ‘educator of the people’ complains that he is lonely: “You know, there is nobody in the village with whom one can discuss sophisticated topics.” He makes a proposal of marriage to Inger, because he “longs for someone with a little intellectual development, for a friend, a woman with intelligence and acumen […]”. But it is obvious that he has financial motives, both for his proposal and for fine words about intellect, education, and respect for women.

The hero of the play is Anne, Inger’s mother. This energetic farmer’s widow has both feet solidly planted in the rural community. She is not to be charmed by the urbanite’s fine words and gestures, and she immediately sees through his motives, turns him down flat, and reminds him that she owns the farm – a role which she did not actually share with many of the real farming women at the time. Otherwise, Anne represents the female values of the rural community: a woman should be physically strong and capable of perseverance in her work, have the ability to make concrete judgements and take resolute action. An ideal of womanhood in complete contrast to that of the bourgeois urban community, where women should preferably be delicate, beautiful, passive, and servile.

Inger is also proactive like her mother. She is bold and, in her own way, skilful. But according to the moral compass of the play, she has got the wrong end of the stick as far as modernity is concerned: new-fangled ideas that cannot be integrated into rural culture are rejected. Inger stands for a bragging and somewhat theoretical educative rhetoric, which probably had its real counterpart in the contemporary rural communities.

That the play had such audience appeal in the town as well as the countryside was not simply due to the fact that it is a well-composed work for the theatre, but also because it addressed a conflict with which the rural population could identify, and was written in a language that was their own.

From the time of her first publication in 1892 until her death in 1934, Hulda Garborg wrote in all a good forty books. Approximately half of them are written in nynorsk: plays, novels, short stories, poetry, philosophical texts, collections of folk ballads, food recipes, and books about housekeeping and bunad (traditional folk garments). Not all of her output was equally well-written or tightly structured, but as a playwright she came a long way, also in an artistic sense – she wrote thirteen plays in all, seven of which were in nynorsk.

The Women of Folklore

After the turn of the nineteenth to twentieth century, the nynorsk movement took a different angle. The previous decades had seen rural culture and agricultural life depicted in opposition to the culture of the town and the official class. The political climate now changed. Various groups who had been in confrontation with one another politically and culturally came together in order to ensure dissolution of the unequal union with Sweden.

Weight had previously been placed on the social aspect, whereas now the nynorsk movement took on a more national character. This change had consequences for the writers’ work – emphasis was now on creating a classic, national landsmål literature, one method being to show the connection between the early Norse and the European cultural tradition.

Most of Hulda Garborg’s Danish-Norwegian (riksmål) plays are comedies and critical-realistic contemporary dramas set in bourgeois urban settings – Hos Lindelands (1899; At the Lindelands), Noahs ark (1899; Noah’s Ark), Edderkoppen (1904; The Spider), and April (1905; April). The nynorsk plays take several different literary directions – from critical realism and dramatic verse based on the oral tradition to more experimental symbolism. All these plays are set against a rural backdrop; most of them take place outdoors in mountain and forest scenery, but should the action move indoors, into the peasant home, then the farmyard, the stable, and the other rustic surroundings are generally included in the stage setting.

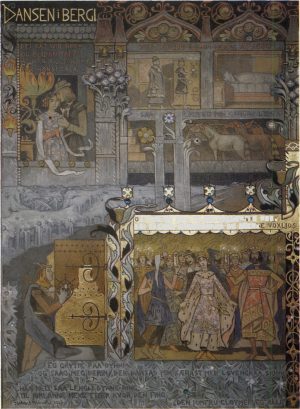

For the singspiel Liti Kersti (1903; Little Kersti), Hulda Garborg has taken material from the folk ballad of the same name. In the stage version, however, the role list has been extended, and theme and psychological analysis are more complex. More than half of the lines are in verse, and the rhythm and lyrical language are close to the folk ballad style. The tale of falling under a spell becomes a story of unresolved love that inhibits creativity.

Kersti’s father, a goldsmith, is desperate – he has lost his creative powers. He consults with the Mountain King on the matter, and is assured that he will get his powers back if, that is, he takes Kersti to the mountain – where she will remain with the Mountain King. But Kersti is in love with the impoverished fiddler Bjørgulv. She proposes to him, but he does not dare embark on a relationship with her because she is socially superior to him. Furthermore, he has a sense of loyalty to another – now deceased – woman: the river sprite had taken her and, in return, given Bjørgulv his musical ability. The conflict between creativity and repressed love is thus linked to several characters. Little Kersti is split between her father and the man she loves.

Throughout the whole show, singing and dancing handmaidens illustrate Little Kersti’s shifting frame of mind, and elements from nature symbolise the conscious and unconscious forces in the human psyche.

Together with Bondeungdomslaget (Farmer Youth Association) in Bergen, Voss Ungdomslag (Voss Youth Association) went to Christiania and performed Sovande Sorg at Fahlstrøms Theater. A few weeks before the premiere, Hulda Garborg wrote in her diary about how worried she was:

“ […] on the 6th and 7th the the group from the west of Norway are going to perform ‘Kråka’ [Swedish for ‘crow’] by Tvedt and also ‘Sovande Sorg’ at Fahlstrøms Theater. If it goes well, then all will be fine. I have in vain given warnings and predicted trouble. Oh dear, here in this cold-hearted town; that is, cold-hearted as regards everything Norwegian. And right now, in the middle of the language dispute. And in June!”

Hulda Garborg: Dagbok 1903–1914 (publ. 1962; Diary 1903-1914)

A similar elaboration and interpretation of the women from folklore is found in the comedy Tyrihans (1915). Iselin is a spoilt and world-weary princess. With a play on the ‘Is’ (ice) in her name, she is also called Istap (icicle), Ishjerte (frozen heart), and Stenhjerte (stony-heart). Flashbacks show us her childhood, when she was both spoilt and high-handed. Now, when she is on the way to becoming an adult, she is no longer allowed to decide things for herself – who she will marry, for example. Word is send out across the entire realm, the one who can make her laugh will win the princess and half the kingdom. Seven hundred suitors make their attempt, in vain; and then Tyrihans takes his turn – with imagination, humour, and disdain for polished manners and social barriers. The relationship between princess and pauper represents an alternative to more traditional and unequal liaisons between sexes and social classes. Hulda Garborg uses material from Norwegian national literature to illustrate equality between gender and class in terms of human and social values rather than as demonstration of national self-assertion.

She also used material from the Norse heritage. The tragedy Sigmund Bresteson (1908) is written in bombastic saga style with dialogue that does not waste words, but has an extensive use of inversion and alliteration. The actual storyline differs little from events in the Faroese saga about Sigmund Bresteson, but in this case, too, Hulda Garborg has given her script a new angle.

Sigmund Bresteson deals with the issue of violence. The hero loses in armed combat, but he wins out in the play because he recognises the wisdom of disregarding personal power and honour for the sake of peace. A rare line of thought for Norse literature, in which demands for blood vengeance and honour are generally more important than your own life and that of others.

Around 1905 in both Sweden and in Norway, there had been discussion about the possible use of military force as a means of resolving the political conflict between the two countries. In both countries, however, there were strong factions, especially on the political left, arguing for a peaceful solution. Hulda Garborg’s play can also be seen in the light of this situation.

Mythical Dramas with Political Ideas

Social commitment and responsibility for the world are also themes in Under bodhitræet (1911; Under the Bodhi Tree) – this time with an Oriental landscape as the stage setting and acted out in a high-flown lyrical language.

Around the turn of the century, Hulda Garborg wrote a favourable article about mysticism and Eastern philosophy of religion, published in the Norwegian journal Samtiden. Other Norwegian writers of the period were also working on plays that addressed philosophy of life and religion. The nynorsk writer Marta Steinsvik (1877-1950), for example, friend and close neighbour of Hulda Garborg, penned two dramas on religious-philosophical themes, Bispen (1918; The Bishop) and Isis–sløret (1921; The Isis Veil). Steinsvik had studied theology and Egyptology, and was very interested in mysticism. Dorothea Reinhardt (1867-1933), with the pseudonym Doris Rein, also wrote a number of Danish-Norwegian plays addressing issues of religion and mysticism.

Hulda Garborg’s Under bodhitræet has stylistic features in common with these dramas, but the play can be seen as a showdown with the esoteric mysticism represented by Steinsvik and Reinhardt.

Den store freden (1919; The Great Peace) employs material from the myths and narrative tradition of the Iroquois Indians. Hulda Garborg had been in the US in 1913, for the centenary celebrations of philologist Ivar Aasen’s birth. In New York she saw a production of Hiawatha performed by Native American Indians, based on Henry Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha. The story of Hiawatha and the confederacy he brought about made a deep impression on her and was the inspiration for her final landsmål drama. In Hulda Garborg’s version, Hiawatha confronts the enemy unarmed, but with inner strength and belief in his peace policy. His is motivated by love for his people. Tribes that had previously been at war with one another meet to negotiate, once Hiawatha has convinced them to lay down their arms; women chiefs also take part in the discussions and negotiations in this onstage confederacy.

The First World War came to an end in 1918, and when Hulda Garborg published this drama in 1919, she had thus seen the consequences of war and militarism at close quarters. She wanted, as did Nini Roll Anker in her play Kirken (1920; The Church), to plead for a political policy that did not set self-assertion and power as the goal, but aimed at understanding and reconciliation between peoples and nations.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch