The Icelandic author Unnur Benediktsdóttir Bjarklind (1881-1946) chose the pseudonym Hulda, which means the subterranean, the hidden.

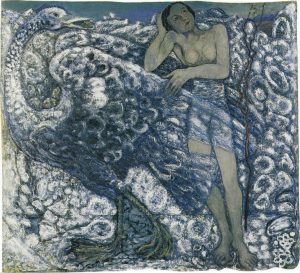

Hulda often draws on Norse mythology when she wishes to express conflicts between the desire for freedom and the need for security. She refers to both the valkyries and fairy-tale swan maidens, who form a strong and ambivalent metaphor in her universe. Swan maidens can transform themselves into swans and can fly. Now and then, however, they must shed their swan disguise, and if a man is able to keep the woman’s plumage, she becomes his – until the longing for her lost freedom causes her to find her wings, abandon her children and husband, and fly away.

Hulda had had to make a similar choice in her own life. While living in Reykjavík during the winter of 1904-1905, she made her debut with a few poems in the women’s paper Framsókn (Progress). She was immediately declared to be one of the most distinguished representatives of the new generation of poets. She nevertheless chose to return home to the north, where her fiancé was waiting for her. Aside from being a mother and the housewife of a hospitable home, she became a prolific author. Her first poetry collection was published in 1909, the last posthumously in 1951.

Hulda was born on a farm in the north of Iceland and received a good education, including private lessons in Danish, English, and German. Her father was a nationally renowned cultural figure, and the county library was housed in his home. There one could always find the newest and most topical foreign literature.

The critics focused on the controlled style, the verbal and formal innovations, but Hulda was criticised for being monotonous and for writing poetry about subjects that were not worthy of being poeticised. “One becomes tired of all these poems about Icelandic nature”, one reviewer writes, and another complains about the “weak, superficial women’s dreams, and a longing that most men, at any rate, will not be able to understand”.

In Hulda’s early works, a battle is being fought in the young female artist’s soul between, on the one hand, the expectations of duty and family, and, on the other, the dreams and desires of the girl.

Hulda’s stern mother-ideal is highlighted and glorified in many of her texts, for example in the short story “Myndir” (1924; Pictures):

“Women must be versatile, but also stronger than the roots of the mountain, they shall be capable of everything, should love everything […] They must be suns, providing spring and summer to all the worlds […] springs that never run dry, but instead water the fields of others – all fields – that forget where they come from and where they are going – because otherwise everything shrivels and dies”.

Hulda was herself the mother of four children, the first of which died shortly after birth.

In Hulda’s later poems and short stories, motherhood is viewed as incompatible with freedom, art, and even true love. In the poem “Hlaðguður” (1926), a woman sits embroidering beside her young daughter’s bed. As in the adventure of Snow White, the red blood drips onto the white material. But the female narrator of this poem ought not to display the queen’s tears and longing – she has her child, has she not, and surely cannot wish for more? At once, she is gripped by a feeling of guilt towards her daughter, and swears that the child shall never suffer because of her mother’s longings and feeling of wasting her talent.

Hulda’s most original contribution to Icelandic literature, in her first poetry collection Kvæði (1909; Poems), is the resurrection of “þulur” (folk rhymes), which was first and foremost a women’s genre.

In the traditional history of Icelandic literature, Hulda’s ground-breaking role in the move towards a greater freedom of form – her collection of prose poems was published as early as 1920 – has not been fully recognised. Two of Hulda’s somewhat younger, male fellow writers have been assigned the honour of introducing to poetry the enigmatic and mysterious quality of ballads, even though they made their debuts some years after her. A third male author is accorded the honour of the first prose poem – but Hulda is at any rate granted the role of having renewed the women’s genre þulur.

Hulda’s folk rhymes are poetically arranged; she employs the hypnotising rhythms and development of the old folk rhymes, but extends the tradition and breaks the rhythm up in order to emphasise her themes. The folk rhymes gain metaphors, associations, and a symbolism that is not found in the old folk tradition.

The folk rhymes’ rhythmical play with language and rhyme traditionally took place during the activities of daily life. The rhymes rarely had beginnings or endings, but ceased of their own accord when the mother or grandmother did not have time for more, or when the children had fallen asleep. The rhymes often deal with daily life, and sad refrains often express the women’s worries and melancholy. The best rhymes survived, some were written down, but most of the authors are unknown.

In her first three poetry collections, Hulda experimented with the form. Inspired by symbolist poetry, she prioritised rhythm and sonority over traditional prosody. She held on to alliteration, but varied the rhymes and the lengths of the stanzas. She became one of the pioneers of prose poetry within Icelandic literature. In her first prose text, “Álfhildur” (1905), the borders between lyrical poetry and prose, dream and reality, are fluid. Human beings, subterranean creatures, and a personified nature merge into one another, and the text is extremely charged with emotion.

The Green World

In Hulda’s first collection of short stories, young people always meet out in nature. They leave the farms and set out for the valleys and mountains, out to the sea and down to the rivers, in order to be together.

Depictions of the passionate love made possible by nature are not uncommon in the women’s literature of the times. The female characters of the Norwegian Ragnhild Jølsen meet their mysterious lovers out in the forest, and in the Finnish Aino Kallas’s Sudenmorsian (1928; Eng. tr. The Wolf’s Bride), the female protagonist seeks out the wolves at night. Only in nature can the young women meet the man who awakens their desire. For some reason or another, this man is often an unacceptable partner for the young woman, but during the secret meetings he is perfect and is presented as a mystical, divine figure.

The American literary historian Annis Pratt has detected a pattern, amongst women writers, that she terms “the green world” of the women. Very young girls are here depicted as children of nature: they are drawn to nature in order to live out their freedom, wild and unruly, fleeing their duties as daughters of the house. Young marriageable women also seek out nature, where they meet their lovers. But both the girl and the young woman are forced back to their ancestral homes. Only the old women are allowed to remain in nature – as hermits, fortune tellers, herbalists, or witches.

In Hulda’s short story “Almar Brá” (1941), the main character, Svanhvít, a female artist, leaves her family in order to study – as it is termed. In actual fact, she leaves her husband and children because of her passionate love for a man, Almar Brá, who is described as “a young god, the god of the lakes, of the rivers, and of love”. The lovers meet in nature, and the symbol of their love is a “dark-red flower” from the mountain meadow. It is not eroticism that plays the main role, but rather the mutual seduction that takes place during the lovers’ soulful conversations. Svanhvít’s love is awakened when she reads Almar’s first book: “In it beat the heart I had always sought”, she says. But the dream of the perfect physical and psychological union with the loved one takes place only in the text. In ‘real life’ there are children who wait for mother to come home.

In many of Hulda’s short stories and poems, there is a ‘holy grove’ that acts as a haven for forbidden love. The poem “Þar dali þrýtur” (1926; Where the Valleys End), describes just such a holy grove, at the end of the mountain’s deepest valley. It is a lost or hidden paradise, and both love and the guardians of love, the Norse goddess of love Freja and her sisters, live there. They try to help and support the infatuated and the unhappy, the outlaws of the world.

The Dream Must be Sacrificed

Hulda’s only novel, the two-volume Dalafólk (1936-1939; People of the Valley), also deals with the conflict between, on the one hand, an erotic attraction and longing for freedom, and, on the other, the demands of society.

Ísól is the only child of a wealthy farmer; her mother is dead. She grows up with freedom and love, and she develops into a beautiful and intelligent child of nature, who swims naked in the rivers, rides wild horses, and climbs the mountain. She can, moreover, play the piano, compose music, and write poems.

Ísól is engaged to her childhood sweetheart when she meets her true love. She spends a few weeks abroad with this man, but at the beginning of the First World War he goes to the Front and is killed. In desperation, she returns to her rejected fiancé, who comforts her, understands, and forgives.

Gradually, she and her husband become leading figures in the cultural life of the region, and this social recognition compensates for the dream of freedom and true love. The explanation for the happy ending to Ísól’s story lies in her husband’s extraordinary characteristics. The traditional gender roles are turned upside down in their relationship – she is the restless wanderer, he is the faithful Penelope waiting for his Odysseus.

The main character of the second volume of the novel is Ísól’s daughter, who is just as beautiful and quick-witted as her mother. But unlike her, she nurtures no dreams of another kind of life, of movement, of the kind of unimpeded access to the world that men have. When she, like her mother, wishes to fight, it is not for herself but for her family’s ideals and the good of the world.

Dalafólk,in particular the second volume, is marked by conservatism and excessive national-Romanticism, a tendency that was prominent amongst well-off Icelandic farmers. The “Nordic” characteristics are accentuated and idealised, as is the Icelandic cultural heritage. Hulda’s heroes are strong characters: they are grounded in the earth, the family, the old values and traditions. The town, socialism, and the workers’ movement are bad elements. The women are often vehicles for that ideology. They are portrayed as hard-working and practical, brave and strong-willed farmer girls. They have neither the sensitivity nor the romantic dreams of the female characters in the earlier short stories. The forbidden love has lost its fascination and its tragic dimension. The unknown lover makes an appearance, but is exposed as a mere womaniser. The proud woman he seduces is ashamed of her weakness and decides to keep, in the future, to the narrow paths of virtuousness.

Dalafólk was criticised, in the 1940s, for idealising the farming community and for lacking realism. The novel was read by many as a reaction to Halldór Laxness’ depiction of the drudgery and misery of the peasants in the socio-realistic novel Sjálfstætt fólk, (1934-35; Eng. tr. Independent People). In a letter written in 1939, Hulda expresses a hope that her novel will be translated “in order to show the world another picture of my people than that drawn by H. K. Laxness. Yes, I allow myself the liberty of declaring that my picture is truer than his”.

Translated by Brynhildur Boyce