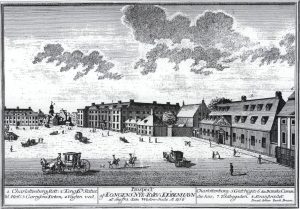

In his late-1740s periodical La Spectatrice Danoise (The Danish Spectator), the professor of French language and literature Laurant Angliviel de La Beaumelle had complained that there was no talent in Denmark for writing in the style of the new serious French plays. In the decades that followed, however, just such talent emerged: first, the young actress famous for her Holberg roles, Anna Catharina von Passow, and later the widely-read spinster Biehl, who had begun promoting the French comedies with a group of friends at Charlottenborg Castle in the centre of Copenhagen.

Anna Catharina von Passow (1731-1757) had influential relatives and close friends in various Copenhagen theatre milieus; together with her young Norwegian friend, later Mayor of Trondheim, Niels Krog Bredal, she introduced the Norse pantheon on the dramatic stage, and also tackled the new French bourgeois comedy.

Anna Catharina von Passow was related to a member of the management board of Den danske Skueplads (The Danish Theatre, became the Royal Theatre in 1772) and the chamberlain and privy councillor Wolrath August von de Lühe, and she was one of the group of friends who put on Bredal’s singspiel Gram og Signe, eller Kierligheds og Tapperheds Mesterstykker (Gram and Signe, or the Masterpiece of Love and Fortitude) in 1756.

Charlotta Dorothea Biehl (1731-1788) continued with her theatrical enterprises throughout the 1760s, and in the 1780s the Nordic pantheon found another female champion in Birgitte Catharine Boye (1742-1824), whose writer contemporaries included Johannes Ewald. Ewald ousted Charlotta Dorothea Biehl from the theatre, and he filled the role of creating grand dramatic art based on the very Nordic pantheon that Passow had actually introduced onto the stage.

The eighteenth-century women dramatists cover a wide spectrum of styles. Even though both Passow and Boye wrote pastorals, they soon branched off in different directions. Boye devoted her pen to the heroic drama, and Passow began to experiment with the new form of comedy, which was the genre on which Biehl concentrated. While Boye’s stage art represents a high-flown conclusion to the eighteenth-century heroic drama, Passow and Biehl are of an earlier generation; they were innovative and made a major contribution to the continuation of the Danish public theatre in the period following Holberg’s death in 1754.

Each of the three women reaches her own interpretation of the eighteenth-century’s new patriotism, heroism, and idealisation of intellectual and gifted women. However, while Biehl and Passow find their virtuous heroines among the citizens of Copenhagen, Boye identifies the new ideal of womankind among the ladies of the court as well as in the Nordic past.

A Strange Ending

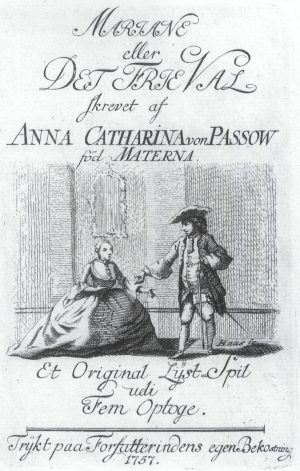

In 1757 Passow published her dramatic works in quick succession and at her own expense: the pastoral play Elskovs– eller Kierligheds–Feyl (Passion, or the Problem with Love), the short one-act Den uventede Forlibelse eller Cupido Philosoph (Unexpected Love, or Cupid the Philosopher) and the comedy Mariane eller Det frie Val (Mariane, or the Free Choice).

How fain would I have honoured you in song!

But an apprentice I, hence patient you must be.

That high I do not fly, for fear of plunging down

So low perchance I be not found again.

Thus wrote Passow in a laudatory verse composed in honour of Niels Krog Bredal, whose Old Norse singspiel Gram og Signe, eller Kierligheds og Tapperheds Mesterstykker (1756, Gram and Signe, or the Masterpiece of Love and Fortitude) had been a tremendous success, delighting a distinguished aristocratic audience and affording Bredal access to Den danske Skueplads (The Danish Theatre, became the Royal Theatre in 1772) – the management of which, following his triumph, had conceived a burning interest in original Danish singspiel.

In a laudatory verse to Passow, written by Niels Krog Bredal, we read:

Come ye wise ones! But come here only to stand in shame

Given that you have condemned this sex to spinning wheel and loom;

Wit and spirit are not confined to rapier and to hat;

A merry soul is often in a corset sat.

The authoress of our cheerful pastoral play,

Not without envy, I would congratulate.

Persist! I shall my best endeavour to this end,

That she is not soon thwarted in her diligence.

It was not a singspiel, however, but a pastoral play written in elegant alexandrines, and with a concluding sung section, that the management of Den danske Skueplads graciously accepted from Passow. The cast of Elskovs– eller Kierligheds–Feyl comprises three ‘pastoral’ couples. The intrigue revolves around how they misunderstand and mix up their feelings for one another. The “affectionate” shepherdess Cloe loves the shepherd Damint, who thinks that she has deceived him with the shepherd Myrtil, who is loved by the quick-witted shepherdess Philette – who gradually sorts out the various misunderstandings. The ins and outs of the manoeuvres surrounding the couples also involve an attacking lion, a couple of faithful sheepdogs, and a few little lambs. The whole caboodle is put on stage with the purpose of entertaining the audience and elegantly pointing out that human emotions are tricky to navigate, but that comic fun-and-games and bold make-up can sometimes help the right lovers find one other. The three couples are presented in such a way as to represent various stages of love: firstly and primarily, tender friendship, followed by ardent love, and finally the free and easy pact between woman and man. Myrtil enthusiastically exclaims:

My motto from now on will be:

First friendship, then love!

If you give love before friendship,

It will seldom last you long,

If with friendship you begin,

Then friendship will love underpin!

Coridon, on the other hand, settles for stating that “Each loves in their own fashion,/ Mine is relaxed, true and free”.

“Coridon: Poor wretches! Stand you here? You would render up your spirit, (he studies them) Well now! Yet I think you are all alive,” is the humorous opening to the grand reconciliation scene in the pastoral play.

Passow has composed a fine and subtle dialogue for her little pastoral play, philosophising on the nature of love. The Rococo’s refined fascination with all things pastoral is given a fresh and unexpected dimension of parody when the affectionate Cloe eventually tires both of herself and her suitors:

I who have despised the purest glow of love,

Which Myrtil feels for me, and have only longed for thee,

But this is punishment, alas! were only Myrtil here,

I would give him my heart, which to me such bother art.

Passow also gets comedy out of her heroine’s deathly pallor when the conflict comes to a head:

Philette: You sigh? my dear! It pains me

to find you so troubled here, Your eyes are dulled,

So pallid is your air, your colour fading –

Cloe: Ah, for my skin what do I care.

The humorous and paradoxical dimension of Passow’s first pastoral play recurrs in the short one-act Den uventede Forlibelse eller Cupido Philosoph, in the preface to which she comments that her inspiration to write a mythological play came from the Swiss professor Paul-Henri Mallet’s writings on the history of Denmark and the Norse pantheon (Introduction à L’histoire du Danemarch où l’on traite de la religion, des moeurs, des lois, et des usages des anciens Danois, 1755; Monuments de la mythologie et de la poesie des Celtes, et particulierement des anciens Scandinaves, 1756; Eng. tr. Northern Antiquities). Mallet was of major significance in disseminating Norse mythology to English-language and German-language writers.

“I was immediately shown two books, from which I could glean a complete, or at least adequate, enlightenment in this matter. These were the deserving Honourable Professor Mallet’s introduction to the history of the Danish realm, and the French translation from his hand of the Icelandic Edda.

“I should give thanks to this learned foreigner for the flame he has lit in me and others of these shores who are not versed in learning,” writes Passow to “the sympathetic reader” in the preface to Den uventede Forlibelse eller Cupido Philosoph (Unexpected Love, or Cupid the Philosopher).

Passow became fascinated by the Old Norse pantheon and, with a sure sense of the dramatic seam to be mined in this new interest in Norse mythology, she chose confrontation between Roman and Norse gods as a central theme in her play. Little Roman Cupid is on an excursion in the foreign and unknown North, where he hopes he will finally be accorded the status of adult and respected god, who compares with Jupiter.

I like Apollo among the gods would be,

not like a child. I can no longer bear

that I alone of all the gods shall be

turned aside with apple and with pear.

Mischievous Cupid has decided to read philosophy, meaning to devote himself to the study of morality, but he lacks the necessary patience and starts shooting his arrows at the Norse gods instead. They do not really have the desired effect on the goddess Freya, however; she sticks to her love of a handsome but fickle husband, Odrus, and in return is rewarded by Alfader (the Almighty Father), Odin: her tears spilt on account of this unfaithful husband will turn to gold. The gods consider breaking all Cupid’s arrows, but instead decide to force him into philosophical study and hold him in custody in the North. Thus, virtuous and faithful Freya triumphs over the impudent little Roman boy, and Passow succeeds in shooting the barbed arrow of her wit at self-satisfied Norse gods and pleasure-seeking Roman pantheon alike.

“O sweet Odrus! Wherefore have you so forsaken me? What other love has wiped me from your mind? How often have my arms enfolded you, And you returned a thousand kisses true,”

– sighs forsaken Freya. She does not, however, allow herself to be affected by impudent Cupid’s arrow, and he starts fearing punishment from the Norse gods:

“The cold sweat runs from my head down to my nose; Why silly boy did I not stay with my book? Now before them shall I a fool look.”

Passow’s play Mariane eller Det frie Val is more serious and less liberated vis-à-vis its genre than her first two short pieces. But it was also a brand new genre that she was attempting to put on stage, and the play shows her talent for assimilating the modern bourgeois French comedy that gained a footing at Den danske Skueplads in the 1750s, when Destouches’ plays were introduced into the repertoire.

In Passow’s grand comedy, four annoying suitors pester the unfortunate Mariane with their incessant declarations, entreaties of love, and never-ending jealousy. The suitors plot against one another, scuffle, and frequently resort to the rapier in order to determine who will be the “owner” of virtuous Mariane, who has had a modern, rational, and independent upbringing in the home of her paternal uncle. Her four suitors all presume that their interest and emotional commitment give them the right to manipulate Mariane and make claims on her.

“Leave me in peace! I know what I shall believe, and not believe! For that matter he can be certain of my retort for all further indecent onslaught,” is Mariane’s straightforward comment to one of the tiresome suitors.”

When the play opens, Mariane has already been through one love story, but she has dropped her beloved because he “infuriated” her with “undue jealousy”, “vehement reproaches”, “apprehension”, and “complaints”.

This first suitor and the next three are all victims of their emotions. They are bewildered and cunning and they shower Mariane with alternately false and honest declarations and assurances. Offering marriage is a release from their emotions. The suitors off-load their feelings onto the woman, thus turning them into her problem and her conflict. Not only must Mariane keep track of her own emotions, but by way of their proposals she is also forced to solve the four suitors’ problems.

Anna Catharina von Passow ends her comedy by allowing Mariane to make “a free choice” by not marrying any of them. She simply rejects the notion that she is responsible and under any obligation to the men’s emotions. “What a strange ending! Of four suitors not to get one?” exclaims Mariane’s confidante Agathe at the prospect of this unusual conclusion to the courting comedy.

“Cruellest of all womankind! How can she bring herself to leave me in the most dire circumstance known to any lover at any time; And caused by her callousness. Nay! Do not believe she shall escape so lightly,” threatens the suitor Eraste. The final suitor, Leonard, repays Mariane’s rejection by trying to set fire to her chamber.”

Passow’s dismissal of the entire squad of suitors was a thought-provoking moral for the Copenhagen bourgeoisie, an audience whose growing requirement for navigating the human emotional relationship map, laughing at their own mistakes, and receiving life instruction, Passow was happy to meet. The “strange ending” to the comedy was also, however, an artistic strategy that made it more than clear to the audience that Passow had shaken off the usual theatrical device of endless conflicts between patriarchal fathers and their sons or daughters who have fallen in love with someone, and was now letting a new ideal of the female character – the intelligent and talented unmarried woman – assume responsibility for herself.

An Exceptional Secret

On 17 October 1764, a new comedy was premiered at Den danske Skueplads. Its title was Den kierlige Mand (The Loving Husband), and the theatre buzzed with rumours; the audience was unsure as to whether it was a new original comedy, and only a few select people knew the identity of the playwright. Private Secretary to Christian VII, Elie Salomon François Reverdil, thought that the author must be the learned member of Selskabet til de skiønne nyttige videnskabes Forfremmelse (Society for the Promotion of the Beautiful and Useful Sciences), popularly known as Det Smagende Selskab (The Society of Taste), Bolle Luxdorph. The secretiveness surrounding the new comedy soon came to an end, however. After the first – successful – performance, Frederik Horn, who, as member of the theatre management, had been party to getting Den Kierlige Mand put on stage, demanded that the writer’s identity be made known. The comedy had been written by thirty-three-year-old Charlotta Dorothea Biehl, and concealment of her name had been a provision that she and her friend Vilhelm Bornemann had agreed with Frederik Horn. They had wanted to make sure that reception of the comedy would be free from prejudice – the audience might not have been keen to see an unknown spinster following in Baron Holberg’s footsteps.

Prior to her playwriting debut, Charlotta Dorothea Biehl already had four years’ experience in the practical side of theatre work. She had been an actress and a translator in a little amateur theatre company, the brain-child of her friend Count Danneskjold-Laurvig, which her father had given her permission to set up in Charlottenborg Castle.

In 1761, she completed her first translations for Den danske Skueplads: two plays by her favourite dramatist Destouches, L’Homme Singulier and La Poete Campagnarde, both of which were staged at the theatre. In her autobiography, Mit ubetydelige Levnets Løb (My Insignificant Life), Biehl explains, with carefully measured modesty, that she had begun writing her own comedies because she wanted to show her friends – the prompter in the amateur theatre troupe Vilhelm Bornemann and the distinguished Councillor of State Augustin – that she could not write anything that was any good. She relates how Bornemann and Augustin made a secret agreement as to how they could induce her to write her own comedies. Once Biehl got going, however, she worked swiftly. Den kierlige Mand took a fortnight to complete. In haste, she invited Bornemann over and he read it on the spot. He was very enthusiastic about the comedy and asked for a cup of coffee to be served while he went through the manuscript again with a critical eye.

What Biehl herself called a “peculiar” – that is to say, exceptional – secrecy surrounding her first play marked the beginning of a period in which she was the theatre’s leading writer. Her key oeuvre comprised the seven comedies written in the period from 1764 to 1771, and published in a collected two-volume edition in 1772-73. Also in this edition were Biehl’s three theatre prologues. In the polemical play Tvistigheden, her spokesperson, the cultivated and well-read Ariste, explains that a good comedy writer must know the rules applicable to the genre, must have read the principal works of the genre, and, above all, must have an insight into “the human heart and all its motivating forces”. Biehl was able to live up to her own demands: she had practical experience and theoretical understanding of the dramatic art. Experiences from her own life had taught her about tender and hard hearts. Rather than paying a fee for her first comedy, the theatre management offered Biehl free use of a box in the theatre. This she made frequent use of, and she continued to study the human heart in her new milieu.

Biehl’s major work consists of the seven comedies staged during the period 1764 to 1771: Den kierlige Mand (1764; The Loving Husband), Haarkløveren (1765; The Quibbler), Den forelskede Ven eller Kierlighed under Venskabs Navn (1765; The Enamoured Friend, or Love by the Name of Friendship), Den listige Optrækkerske (1765; The Cunning Fraud), Den kierlige Datter (1768; The Loving Daughter), Den Ædelmodige (1768; The Noble-Minded Man), and Den alt for lønlige Beiler (1771; The Too-Retiring Suitor). The two-volume edition of her comedies also includes her three theatre prologues: “Melpomenes og Tahliæ Trætte” (Melpomenes and Troubled Tahliae), “Den glædede Thalia” (The Merry Thalia), “Den forsvundne Angest” (The Vanished Trepidation), and her polemical play Tvistigheden eller Critique over den listige Optrækkerske (The Dispute, or Critique of the Cunning Fraud).

Tender Dialogues of the Heart

Biehl admired her predecessor in the art of comedy, Ludvig Holberg. She had read his comedies during her childhood, and she had learnt from them, even though her great role models were the French writer Phillippe Néricault Destouches and the Italian writer Carlo Goldoni. Like Destouches, Biehl based some of her characters on the old commedia dell’arte gallery: the patriarchal father-figure Hieronimus, his wife Magdalone, their marriageable daughter Leonora, the servants Henrik and Pernille, and Leonora’s suitors.

In Holberg’s comedies, a temperamental and injudicious character is placed at the centre of the comedy and the machinations of the plot. In Biehl’s plays, the comical and temperamental characters have subordinate roles. Young daughters and sons of marriageable age have been brought into the foreground. The young daughter or wife Leonora is often the central character in Biehl’s comedies, and a noble and sensitive friend of the family plays an important role in the plot itself.

Leonora’s comic suitors are related to the figures from the old commedie dell’arte tradition: the learned pedant, “il Dottore”, and the bragging soldier, “il Capitano”.

The emotions of a tender heart have taken over the role of common sense as the best and safest foundation of our lives. In Holberg’s comedies, friction around marriage and engagement serves to fuel the plot and activate the temperamental and injudicious characters. In Biehl’s comedies, the story of the marriage is the main thrust of the play; her setting is the drawing room of the bourgeois home, where the characters converse about their feelings for one another. The tender hearts prevail, and the deep emotions lead to good moral conduct.

Biehl rarely allows the comic element to dominate. She places greater weight on the characters’ discussions of feelings than on creating comic incidents involving the ignoble and insensitive subordinate characters. The servants Henrik and Pernille, who were important agents of reason in Holberg’s comedies, play an insignificant role in Biehl’s work. Henrik is often a foolish suitor’s servant, and scenes between Henrik and Pernille are lulls and padding in the storyline. The tender hearts must be allowed to rest, and the audience be given time for reflection, while Henrik and Pernille flirt in accordance with a fixed and familiar pattern; Henrik cajoles Pernille with the promise that he can make a married woman of her if she will help his master win over her mistress.

In her first play, Den kierlige Mand, the Henrik and Pernille scenes are given greater prominence than in the later comedies. The two servants have allied themselves with the loose-living Baron, who wants to seduce both Mademoiselle and Madame, and artful Pernille intends to persuade her mistress to be just as coquettish as most of the ladies in Copenhagen: “Although it has come so far that she, like most of our ladies, no longer concerns herself with either her home or her children; but spends half the day about her toilette, and the other half on visiting, card games, plays and dancing; yet still she has the ludicrous caprice to love her husband.”

In order to highlight that the conflicts in the comedies deal with the everyday lives of the audience, Biehl mentions from time to time that the bourgeois home is found in Copenhagen, and her characters talk about the city. In Den kierlige Mand, the bourgeois family have very recently moved from the island of Funen to Copenhagen, and the young wife Leonora has therefore not yet been spoiled by the many amusements available in the city.

Pernille has an important function in the most humorous of Biehl’s comedies, Den listige Optrækkerske: she sets off the conspiracy against Lucretia, a deceiver of men. Her motives, however, are also egoistical: Lucretia has boxed her ears, and Leonard has offered her fifty ducats if she will expose Lucretia. In Den Ædelmodige, Pernille is for once virtuous and kind-hearted, and it turns out that she is actually an unmarried lady of rank who has disguised herself as a servant girl to escape a nasty suitor.

In her comedies, Biehl shows her audience a gallery of characters with vastly differing attitudes to marriage, and with different opinions about what marriage ought to be. Children, young women, respectable matrons, impulsive patriarchs, loving daughters, loyal husbands, noble suitors, cool-headed friends of the family, egoistic servants, and cynical hypocrites are given the floor by turn in the lengthy exposition of assorted ideas on marriage that is presented in the comedies.

In Den forelskede Ven, Biehl introduces her audience to the respectable widow Magdalone who gives her daughter, Leonora, permission to make her own choice of husband. Leonora, however, has no desire whatsoever to get married. She prefers a calm life in her mother’s household. She is sure that she “would be far happier with the advice and attendance of a sensible friend than with the mastery of a husband”. Leonora has just such a friend in the person of Leander, and she disdains her suitors’ adoration; the power she is claimed to exercise over hearts is, to her mind, a pest and persecution.

“So it is proof of her power that they persecute, torment and harass her? I know in advance what each has to say: the one’s heart pines for me; the other will give up all the gold in Peru to demonstrate the ardour of his love; the third keeps so close to me that I can barely move, and is quick to slay the other two with his eyes; should he now and then speak a word, the gist is the same as the others’: Love me! which is to say: become just as hapless as we are.”

(Leonora in Den forelskede Ven)

Leonora’s ten-year-old sister Lise would, however, be quite happy to take on the many suitors. She childishly falls for their compliments, kissing of the hand, and gifts. Lise is an interesting and highly accomplished comic character. Biehl had already put a child on the stage in her debut play, Den kierlige Mand, and children were on the cast list in the new French bourgeois comedy, but Biehl was the first Danish dramatist to give lines to a child character on stage.

Den forelskede Ven, of course, ends with Leonora’s trusted friend, to whom she has moaned about the suitors, becoming her husband.

“For so long as your heart is mine, no power can separate us. A father has no right to demand outrageous things of his child,” the sensitive suitor Leander says to comfort his Leonora in the comedy Haarkløveren

.

True love starts, according to Biehl, with high mutual esteem and friendship. As in Anna Catharina von Passow’s philosophy, love is an alliance of esteem, friendship, and “affection”. In a number of her comedies, Biehl’s Hieronimus character asserts his paternal authority over Leonora, and she does not defy him even though he acts foolishly, selfishly, and insensitively. When Hieronimus’ preference is for a hypocritical suitor, his decision is set aside. Hieronimus is not cured of his hefty and ugly temperament, his selfishness and thoughtlessness. His authority endures, but time after time the tender hearts strip him of his power. In Den kierlige Mand, Biehl was already looking at the change of power between old-fashioned Hieronimus and the new, sensitive man, making Hieronimus a more positive figure than in most of the later comedies. He is a widower, who is happiest in the company of a glass of good wine. He has given up trying to impress the ladies: “Should you want to have the benefit of them, then ideally one must caress them, and I can no longer be bothered to do so,” he explains. He has handed over his authority to Leonora’s loving husband, Leonard. But it is his criticism of Leonora’s excessive lifestyle that leads Leonard to intervene and awaken his wife’s feelings by showing her that she has been neglecting their child. Hieronimus has no interest whatsoever in the child missing its mother, he is talking about Leonard’s risk of becoming a cuckold: “I have by no means in mind to offend you; it is up to you. And if you can endure that it be said: you are a cuckold, then I will be able to endure that it be said: my brother’s daughter is a coquette.”

In Den Ædelmodige, however, Hieronimus’ paternal morality is utterly dubious and callous. His business ethics are also more than open to criticism. Hieronimus pokes fun at the idea of a marriage based on love:

“Believe me, a wife who does not love her husband can make his life enough of a misery, but should he be so unfortunate that she has a fondness for him into the bargain, well, then there will never be any living with her.”

Magnanimous Ariste will not, however, force Leonora into marriage. To his mind, marriage must be based on the compatibility of dispositions, and he says to Hieronimus by way of explanation: “But to make the exercise of duties the more pleasant for my wife, then they must be in accordance with her affection, and therefore I should with my solicitude and devotion first endeavour to win it.”

When Ariste discovers that Leonora loves Leonard, he provides the hard-up wooer with capital and a career so that he can meet Hieronimus’ financial demands of a suitor. Ariste has become a paternal alternative for the couple.

The audience has been thoroughly instructed in the dangerously egoistic nature of Hieronimus’ actions, and they have seen the tender hearts come to power.

“And can you be so ridiculous as to take this woman willy-nilly into your heart? It is nothing other than foolery, which the accursed novels have put into her mind. She would at times imagine herself to be such a heroine, sighing and weeping over her father’s tyranny; but this you should know, there is never a suggestion, no matter how sensible, to which she will not find some objection, if it has not come from the mind of a woman,” admonishes the old miser Hieronimus in Den Ædelmodige.

Den listige Optrækkerske is Biehl’s funniest and most satirical comedy. The deceiver Lucretia was played by Miss Bøttger, who was otherwise usually cast in Biehl’s ‘Leonora roles’. But Lucretia is no virtuous Leonora. She is a wily gambler on the marriage market, and she knows how to exploit her suitors and trick them out of their money without marrying them. Lucretia’s suitors are, though, no less deceitful than she. Old Hieronimus would exploit her sexually. The Baron hopes to lay his hands on her money. Leander alone is sincere in his dealings with Lucretia. He is deceived by his own feelings. The intention of the comedy is thus to expose the institution of courting, and to show how easy it is for kind-hearted Leander to misjudge himself and Lucretia. She can deceive the men because she is able to act as the woman of their imaginations. With Hieronimus, she is a virtuous and meek child, and thereby excites his fantasies and sexuality. She satisfies the Baron’s fantasies by playing the role of a wealthy, pleasure-seeking but inexperienced heiress. She transforms Leander’s fantasy into a sensitive, cultured, and vulnerable woman who spends her time on books and good deeds.

“Hieronimus: […] there would be no iniquity in it at all, if what you wear about your neck makes you hot, that you then took it off and sat with naked throat in my presence; for I have long since surmounted my desires.Pernille (aside): What an old rogue!Lucretia: The reverence in which I hold you would never permit me so to do.”

(Den listige Optrækkerske)

The life of the emotions is full of perils, deception, and self-deception. The institution of courting is acted out like a masked ball, and Lucretia is prepared to give the men what they want in order, as she says, to be amused by their foolishness and evade the yoke of marriage.

Den listige Optrækkerske caused offence. Bolle Luxdorph personally cautioned Biehl about the morality of the piece, and she felt called upon to answer her critics in the polemical play Tvistigheden eller Critique over den listige Optrækkerske, which was, however, never performed.

An Inhuman Letter

Biehl’s heyday at the theatre was brief. In 1766, she won Det Smagende Selskab’s prize for best comedy with Den kierlige Datter, and several of her comedies were translated into German and Swedish, and also staged in Sweden. In 1771 a young Peder Rosenstand-Goiske launched his theatre review periodical “Den Dramatiske Journal” (1771-73; Drama Journal), on a number of occasions giving Biehl’s comedies a rough ride. He described her characters as “dialoguing machines” and was bored stiff by Den kierlige Mand. The first re-discovery of Holberg cost Biehl her reputation as dramatist, and an up-and-coming star – Johannes Ewald – had already written his comedies. In the 1770s, Biehl tried her hand at three plays in a new popular genre, the singspiel. But when Hans Vilhelm Warnstedt took up the post of theatre manager in 1779, he made it clear to Biehl that he did not wish to receive her original scripts. He sent her what he himself dubbed “an inhuman letter”.

“The malaise, which I still feel every day, and which in all likelihood will end my days, is yet a consequence of this inhuman letter.”

(Mit ubetydelige Levnets Løb)

Warnstedt concentrated his efforts on Ewald who, following the production of Balders Død (The Death of Balder) in 1778, had won the favour of both the royal court and the popular audience, and went on to triumph with the staging of Fiskerne (The Fishermen), which opened on the king’s birthday in 1780. Biehl ended her theatre career executing commissioned translation work. When the theatre no longer had any use for her comedies, she found a new genre to work in – the moral tale – with which she avenged Warnstedt’s inhuman letter.

A Manly Queen

While Charlotta Dorothea Biehl’s bourgeois comedies were dispatched into oblivion in 1780, and Biehl sent petitions, in vain, to Under-Secretary of State and Private Secretary Guldberg in the hope of acquiring Baltic stocks and shares, another female dramatist was enjoying the favour of the royal court and the mighty Guldberg. Birgitte Catharine Boye already had a glorious past as a hymn writer when, in 1778, a second marriage took her to Copenhagen.

Boye received support from the heir presumptive for her son’s upbringing and studies, and when she was widowed in 1775 she herself received support “for her provisions”.

While Ewald celebrated the king’s birthday in 1780 with the drama Fiskerne, Boye chose to celebrate the dowager queen’s birthday on 4 September 1780 with a little pastoral play in two acts. Boye wrote the pastoral play Melicerte, published 1780, for the small theatre in Fredensborg Castle. “God grant that this trifle may fulfil my purpose, which is and has been to please my Queen and procure her encouraging applause,” wrote Boye in her respectful dedication. Boye entertained her queen with a good old-fashioned pastoral play set in delightful, southern pastures, where virtuous shepherds woo the beautiful shepherdess Melicerte.

“Shepherds and shepherdesses enter dancing around Melicerte, carrying festoons, one of the shepherdesses places a garland of flowers in Melicerte’s hair as she approaches the altar – they dance, and after the dance they divide to either side of the altar,” writes Boye in a stage direction, and we can imagine the delightful scene presented to the royal audience.

One of the shepherds, Nordan, comes from afar and talks about his Nordic “fatherland”, where “the fruit of every furrow multiplies a thousandfold”, and King Dan’s progeny rule with “wisdom and justice”. Nordan celebrates the strong Queen Dannebod, who has saved the throne. Boye deftly accords Dannebod the dowager queen’s own lineage, and Juliane Marie could see her 1772 coup d’état against Johann Friedrich Struensee interpreted as a truly womanly heroic deed. Dannebod has restored virtue at Dan’s court, underlines Boye, with an indirect reference to the love affair between Struensee and the young Queen Caroline Mathilde, which was brought to an end by the dowager queen’s coup.

Roused by religion

Virtuous vengeance lay on parted lips – – But – –

Unheard sighs snatched away the word

And tears of tenderness fell upon the crimson!

Then my North did weep aloud, so the heavens heard – – –

She then arose with fearful majesty

Like our Semiramis – – – and stood,

While the throne reeled, at the throne – – – –

she gazed with noble defiance and Brunsvig’s heroic mien:

The throne of the Danes shall endure! I shall protect it!

Protect or die, but in its ruins!

Juliane Marie could be satisfied with this high-flown ode and its many dignified pauses or caesuras in the style of the German poet Klopstock, and she could delight in the grandiose arias and dance scenes which added variety to the courting conflict of the pastoral play. With the ode to Queen Dannebod, Nordan wins the shepherds’ singing competition, and with it Melicerte for his bride; he elects, however, to entrust Melicerte to the shepherd she loves. Nordan makes the decision that Melicerte is unable to make due to the duty of obedience to her father, which prevents her exercising free choice:

“Were she less good, then it would be easier for her to choose; but now virtue and love are engaged in dispute within her heart and she dare not take a step by which she might later have cause to reproach herself – she holds Tyrsis in high esteem, she loves Menalk, and feels fondest friendship for me, she will not herself choose — — —”

With his artistry and his Nordic Dannebod virtue, Nordan resolves the conflict and the shepherds enter dancing for a final choral aria praising Danish absolute monarchy:

From a supreme throne

to shelters far below, resounded

these powerful strains of celebration:

joy and happiness.

Boye incorporates all the core eighteenth-century words on love in Nordan’s lines: high esteem, tender friendship, and the nature of loving; and Nordan resolves the suitor-dispute in such a way that Melicerte is able to retain her high esteem for Tyrsis, her tender friendship with Nordan and her love of Menalk.

The unfortunate young queen, Caroline Mathilde, could well have used a rescuing Nordan when Struensee was executed in 1772, but she had long since been removed and, to the relief of the dowager queen, was dead and gone by September 1780, when Boye’s pastoral play was performed for her entertainment.

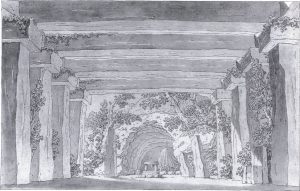

All that was left of Caroline Mathilde’s story was Juliane Marie’s heroic deed and courageous virtuousness. Birgitte Catharine Boye continued her work for the stage with a longer play, Gorm den Gamle. Et heroisk Skuespil i tre Handlinger (1781; Gorm the Old. An Heroic Play in Three Acts). The play was dedicated to the heir presumptive, a not particularly gifted man who lost all political influence following the crown prince’s 1784 coup against Juliane Marie and Guldberg. Gorm den Gamle is a lavish spectacular featuring King Gorm in the role of rallying standard bearer, a hero acclaimed in all the Nordic lands. Boye built freely upon the legend of King Gorm, locating his court at the old royal seat in Lejre, and decoratively settling his daughter, Gunnild, and his queen, Thyre, with their embroidery, outside the king’s “leafy pavilion”.

The king’s daughter is a magnet for wealthy wooers – primarily, the belligerent heir to the Swedish throne, Storbiørn, and the handsome Norwegian king, Erik Haraldsen. But Gunnild has made her oath of allegiance to a Finnish warrior, the dangerous Ragner, who has saved her from two Finnish “virgin thieves”. Gorm has to disappoint Storbiørn:

“It pains me to grieve you; but I must – – – A short while since, I met Gunnild – she pressed this hand to her lips and told me with some unease: that an unknown Ragner, a Finlandic giant, loathsome as a troll, but noble as a demigod, has saved her through combat against two Finns; that this giant has her promise, and that he is coming to Lejre in order to claim my consent.”

Fortunately, “this giant” turned out to be King Erik of Norway, disguised as a Finnish troll, and the grand Nordic drama ends happily with an engagement. Solidarity between the twin realms of Denmark and Norway is given a heroic and mythical explanation; paying no heed whatsoever to actual historical fact, Boye thus complies with the contemporaneous interest in legend, historical myth, and patriotism. While Gorm awaits news from his various battlefields and sorts out the Nordic courting and engagement story, noble Queen Thyre has abandoned her embroidery and initiated construction of the fortifications known as Dannevirke to defend the Nordic region against the Teuton army commanders. “Yes! she is wise, a manly queen, and her Dannevirke will bear her name to the final generations,” exclaims Uffe the skald enthusiastically, and Gorm concurs: “Ha! devout tutelary deity of the age! Heroic Dannebod! Did not sit despondently hands in lap.” Boye did not economise with the heroism and, even though Danish queen-manliness had become a less immediate royal theme after the crown prince’s coup in 1784, Boye’s play was performed to mark the crown prince’s birthday in 1785 – in a splendid stage setting designed by Thomas Bruun – and the text was reprinted by Det smagende Selskab, having first been published in 1781.

The skald Uffe vividly describes the huge Dannevirke: “I have recently reviewed the work – the fortification rests upon a grey rock wall, stretching from Schleswig to the North Sea, and the sea lured forth through the hollowed sides of the earth is already coursing at the eternal foot of Dannevirke, and tower by tower are being built, no more than one hundred fathoms between each, and under each tower a deep gate, and the whole is melded together, so that mountain trolls shall hammer fire thereof.”

Boye concluded her writing career with various occasional poems for royal red-letter days and one more heroic stage play, Sigrid eller Regnalds død (1795; Sigrid, or the Death of Regnald). That same year, she published her poem Tanker ved Kiøbenhavns Ruiner (Thoughts on the Ruins of Copenhagen), a high-flown depiction of the terrible city fires in both 1794 and 1795, when the mighty blaze was with “ghastly splendour […] clad in our property”. Boye does not neglect to celebrate the now powerful crown prince and heir presumptive as comforter and helper of the people:

Christiansborg Palace was of late ablaze, incalculable

was the heir presumptive’s loss! O, were it but his greatest!

But set it right he must, the benevolent prince,

He heard the sigh of poverty, but true to each bounden duty,

He called upon a horde, which despicably squandered it all,

And kindly housed them, and long kept them fed.

Birgitte Catharine Boye was herself fed by her royal patrons, but the poem on the Copenhagen ruins marked the end of her writing career. The Nordic legends and historical myths, with which her generation of eighteenth-century dramatists had been so engaged, found new interpreters among the Romantic poets. Birgitte Catharine Boye chose to remain silent and leave the art of writing to her two sons, neither of whom achieved the same kind of success as their mother.

The Triumph of Virtue

“[…] she and Miss Biehl illustrate how ladies may very well combine housekeeping with knowledge, and that they are ennobled by these just as much as they benefit themselves, their husbands and children,” writes H. J. Birch of Birgitte Catharine Boye in his Billedgallerie for Fruentimmer (1793; Picture Gallery of Women). The woman who wrote in her own name must of necessity display appropriate virtuousness, and her work should serve both her self-education and the education of her audience. In this respect, Birgitte Catharine Boye, Anna Catharina von Passow, and Charlotta Dorothea Biehl all made the most strenuous of efforts. The artistic results were not always of equal quality. Even though Boye’s plays are better than her reputation in the annals of literary history would allow, her writing for the stage cannot be compared with the plays written by the two theatre practitioners Passow and Biehl, in which there is a clear sense that they knew what works on stage, how to set characters off in relation to one another, and how to structure dialogue. Passow’s, and particuarly Biehl’s, skill kept Danish drama alive after Holberg’s death. Their work introduced a new, intelligent, and sensitive womanliness on stage, whereas Boye had some difficulty helping her royal heroines to their feet.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch