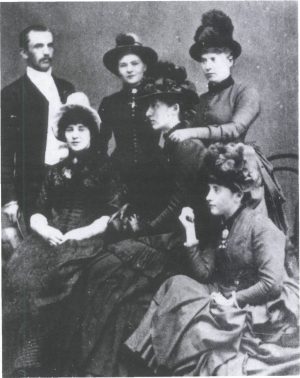

At the time of her death, in 1888, Victoria Benedictsson was a celebrated author. She was the first of the literary group ‘Det unga Sverige’ (Young Sweden) to receive a grant from the Swedish Academy. This signified her having been admitted to the cultural establishment that she had for so long believed herself to be excluded from as a woman and “a pariah, a mangy dog”. Before Victoria Benedictsson settled on the pseudonym Ernst Ahlgren, she had long vacillated between the alternatives ‘Tardif’, the tardy, and ‘O. Twist’, the unwelcome. To Victoria Benedictsson, writing is just as symbolically loaded as her choice of a signature appears to be; it is an analysis of the problems associated with female identity, with being a gender and not a human being. “I am a woman. But I am an author – am I not, then, something of a man as well?” she wonders in January 1888.

Her own life was short and ended tragically. Thirty-eight years old, she took her life in a hotel room in Copenhagen. For a period of a few years in the middle of the 1880s she was astonishingly productive. Her career as an author falls between 1884 and 1888, in which period she published two novels and two collections of short stories as well as several plays and newspaper articles. Simultaneously, she kept an extensive diary and corresponded energetically with many of her colleagues. Her intellectual vitality during this short period stands in contrast to the image of a sickly, doomed person, which has dominated her posthumous reputation.

In the last part of her life, Victoria Benedictsson worked as though possessed on many different literary drafts. In her diary she exclaims: “I want to write about women. And if – after having written the most daring and honest things I know – I still feel as I do now, then I want to die.” Common to these texts is that they deal exclusively with the relationship between the sexes, and especially with the woman’s possibilities for both self-realisation and love.

The Voice from the Dark

Victoria Benedictsson’s extensive literary estate includes a number of drafts that are of great interest both as regards their plots and their aesthetics. The female figures are driven towards disaster, while the style becomes increasingly modern in its pitch black, piercing brevity. Was Victoria Benedictsson’s last insight that the woman can only be described as a tragic subject? The posthumously published prose piece “Ur mörkret” (Eng. tr. From the Darkness) is conceived as a confession. The situation is surprisingly similar to a psychoanalysis, with a male analyst listening to a female patient stretched out on the couch. According to Freud, who around the same time developed his method with the aid of middle-class Viennese women, the role of the analyst is to try to render meaning and coherence to the patient’s fragmented life story. Axel Lundegård, the colleague and friend who ‘inherited’ Victoria Benedictsson’s unpublished manuscript, took that role upon himself when he reconstructed “Ur mörkret” on the basis of the various drafts that existed at the time of her death.

The bitter, languishing Nina of the story confides her wasted woman’s life to a silently listening male friend. “Everything is shameful for a woman because she is nothing in herself; she is only part of her sex.” Nina can be seen as a double victim of the patriarchal ideology that Victoria Benedictsson compliantly noted down after having listened captivated to Georg Brandes lecturing on the different natures of man and woman, in Copenhagen in the winter of 1886:

“A real man primarily possesses power, power in everything he does, power to bend others to fit into his plans, and to use them as tools, power to hold a woman fast!

“And what is ‘the womanly’? The ability to love completely and without conventional considerations: warmly, fully, vigorously. To be brave, sacrificing, strong; everything through love, without jealousy, without any ulterior motive; simply because it is her nature to love.”

The Nina figure is provided with a history that confirms the fact that this ideology is very much in force. She has been exposed in turn to the contempt of her father, her husband, and her lover, and she turns their misogyny both inwards, towards herself, and outwards, towards other women. A modern reader might easily interpret “Ur mörkret” as a paradigmatic account of a typical woman’s lot in the shadow of the patriarchy. But that is not an exhaustive reading. The story is in fact full of contradictions in its investigation of the inner logic of the patriarchal ideology. It turns out to be Nina, and not the men in her life, who possesses the ‘male’ virtues of competence, industry, veracity, and honesty, and this makes the text ambiguous and ambivalent. The insight of the text is greater than that of the plaintive Nina.

In her self-analysis, Nina appears a prisoner of ideology, crushed between the inherent polarities of language: masculinity = good, “everything”; and femininity = bad, “nothing”. In despair she searches, in her language, for a third, utopian alternative, “neither man nor woman, merely a living being”. This construct recurs almost obsessively throughout the story. But to reside in a “merely” – to be a neuter – is an impossibility. All that remains for the woman who does not want to be ‘woman’ and cannot be ‘man’, which is the highly desired condition, is, with a triple negation, a “watered-down, bloodless nothingness”. And this is where Nina finds herself during her long confession. Her body on the couch is literally devoured by a “nothingness”, a “hollow-eyed” darkness, out of which her monotone and tormented voice is heard.

But from this empty position, a resistance is built up, against all odds, when Nina insists on absence. Her refusal to be a woman in the sense of being an object for the man makes her an anti-subject, a “merely”, an empty form to reside in. And gradually the darkness turns out to be the real protagonist of the story, the site of the unconscious, the enigmatic, the utopian, the very hollowness of the language. “Ur mörkret” can be read as Victoria Benedictsson’s literary testament.

Nina’s self-understanding in Victoria Benedictsson’s novel “Ur mörkret” (1888; Eng. tr. From the Dark):

“I had learned to see with my father’s eyes; I saw from a man’s point of view what it means to be a woman – repulsive, repulsive, one great misfortune from our very birth! I felt like a mangy dog. This is when the humility emerged that is my character’s brand and incurable flaw. Oh, the spot in my brain! How soft and sensitive it grew so that each barb could penetrate! How much I understood when it came to this single thing: to comprehend something that was as incomprehensible to other women as the twittering of the birds.”

Two years earlier, she had proudly and full of contempt dissociated herself from what she saw as Alfhild Agrell’s “hollow”, “dreary”, and “sickly affected pessimism”, in order to write instead “so that people get happier and better from reading”. If this were to fail, it would be better, Victoria Benedictsson thought, not to write at all. It may seem as if she, with “Ur mörkret”, had ended up in an aesthetic impasse. And then again! The fact that she did not destroy the manuscript fragments indicates that she had a feeling that it was this kind of contradictory literary texts, which defied unambiguous interpretations, that would ensure her a place in literary history.

The first scholar to take Victoria Benedictsson seriously as a female artist is Jette Lundbo Levy. She sheds light on Benedictsson’s grandiose attempt at presenting a third point of view, distinct from the men’s message of free love, but also from the women’s movement’s puritan reply to this message (with the demand that, before marriage, men had to be just as sexually inexperienced, just as ‘pure’, as women). Lundbo Levy reads Benedictsson at several different levels, compares her private diary entries and letters with published material, and asks herself why Benedictsson did not entirely succeed in describing, in an elaborated literary form, her complex feelings with regard to the dilemma of femininity. What determines Benedictsson’s writing is rather what Lundbo Levy calls “the aesthetics of the double gaze”, the tension between a ‘male’ gaze that creates one literary form and a ‘female’ gaze that creates another. “Ur mörkret” (Eng. tr. From the Dark) is a clear example of this aesthetics and its inherent tension.

The Programme

Victoria Benedictsson’s conscious aesthetics embraces three different writing projects. Firstly, she wanted to write for ordinary people, “for those who work”. Secondly, she wanted to “submit problems to debate”, and, as Georg Brandes advocated, present the great contemporary questions in a realistic, engaged prose. And thirdly, she wanted to describe her own inner development, her ever more trying struggle to make the woman, the human being, and the author hang together. She made her debut as an author in 1884 with the favourably received collection of short stories Från Skåne (From Scania) by ‘Ernst Ahlgren’. In addition to romantic stories about being an artist and being the chosen one, the collection includes a number of descriptions of the lives of common people, with sharply drawn portraits of people from the Swedish province of Scania. In varying ways, the Danish-Norwegian Magdalene Thoresen, the Dane Henrik Pontoppidan, and the Norwegian Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson had already created a tradition of portraying ‘the people’, but Victoria Benedictsson renews the genre by focusing instead on the observer. She lets traditional patterns of life be reflected in the eyes of an outsider, and her sense of humour shoots down every attempt at idyllising. Instead, it is the repetition, the stagnation, and the sluggishness that dominate in her description of country life. A recurring image is the clay that clings to the wooden shoes, holding you back and making your gait heavy and clumsy. “– The road is one big puddle, and the feet get stuck in the clayey soil, which is so sticky that it ties you down […].”

The soil ties you down and holds you back. The feelings of security and homeliness easily turn into the feeling of being cooped up. This was what Victoria Benedictsson increasingly experienced in her own life. Gradually, the life as the wife of a postmaster in an ill-matched marriage in the small community of Hörby became too restricted for her; she longed for wider horizons, new contacts and impulses. The newly opened railway made it easier for the author, who had a bad leg, to travel to Stockholm, Malmö, or Copenhagen. And she grasped the opportunity.

A part of her luggage was her unique literary friendship with the writer Axel Lundegård, ten years her junior, whom she had met at the home of his parents in Hörby. “Complete openness!” was the watchword between the two colleagues, who read each other’s manuscripts and offered each other criticism and praise. It was an unusual, intense, but by no means conflict-free friendship that developed. In their correspondence, which grew extensive in the autumn of 1884, they discussed the craft of writing and the ideas of the time. Both understand that unprejudiced communication with someone of the opposite sex is important, but to Victoria Benedictsson it was invaluable. She writes to Axel Lundegård:

“This is what interests me most in the world: the equality of the sexes, not only in a social context but first and foremost in their own consciousness, for that is what matters. And now I’ve come to something in your letter: ‘If we are to benefit at all from our knowing each other, we have to talk about everything without reservation.’ Yes, yes, yes! There’s nothing I want more than that. Haven’t I, ever since I was a child, been waiting for these words, and no one has said them to me until now!”

The possibilities offered by the period’s patriarchal marriage for “equality of the sexes” is what she examined in the two novels she completed.

Less on account of her writing than of her personal fate, Victoria Benedictsson has become the female fixed star in the literary sky of the Swedish 1880s. As such, she often eclipsed the period’s other female authors. However, it is the image of tragic femininity that emerges in literary history, a frigid, plain, and strained heroic figure, who committed suicide as a result of unrequited love.

This interpretation is based on the comprehensive biographical source material formed by the handwritten volumes of Stora boken (The Big Book). Select parts of this unequalled ‘self-confession’ were published, under the name of the editor, Fredrik Böök, as the ‘love novel’ Victoria Benedictsson och Georg Brandes (1948; Victoria Benedictsson and Georg Brandes). That book has fixed the image of Victoria Benedictsson as the tragic heroine of the 1880s, a mixture of Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler and August Strindberg’s Miss Julie. She is, in fact, considered to be the model for both these characters.

To this should be added that, in contrast to most of her contemporary female colleagues, Victoria Benedictsson adopted a rather humble attitude with regard to the question of the relationship between man and woman. In a letter of 1886, she confides the following theory to her friend Ellen Key:

“If men want to regard us as small, clever pals, then we should be pleased, for this is, I believe, nature’s intent. That a few women – one or two in each century – rise above the crowd, does not change anything for all the rest of us average human beings.”

The (Im)Possibility of Marriage

The novel Pengar (1885; Eng. tr. Money) opens with young Selma being persuaded to ‘sell’ herself to the rich country squire Kristersson. Their intimate life is a torment that soon makes her realise that marriage without love and companionship is not much better than prostitution. Unlike the protagonist of Amalie Skram’s novel Constance Ring (Constance Ring), which appeared in the same year, Selma succeeds in breaking out of her marriage. Pengar is a typical novel of the 1880s, a well-written plea against early marriage and marriages of convenience, but above all against the sexual ignorance that was considered the young middle-class girl’s finest dowry. Victoria Benedictsson does not shy away from describing the sexual life of the spouses. The wedding night is experienced as a rape, and the tale about King Lindworm, who exacted the promise from his queen that she would never enter his chamber when he is asleep, is woven together with Selma’s thoughts about what is most forbidden. For through her marriage she has had the same experience as the queen, who, defying the prohibition, discovered a coiled, “scaly monster” in the king’s bed: “Now her curiosity was satisfied. But she could never forget that sight, and each time King Lindworm took her in his arms, it was as if he resumed the form of the scaly monster, so slithery and cold that his embrace made her writhe in agony.”

Fru Marianne (1887; Mrs Marianne) was Victoria Benedictsson’s great venture. It was to prove to everybody that she was a great author and not just one among the group of emancipated writing ‘ladies’ who were somewhat looked down upon. But to her great disappointment it was received precisely as a ‘ladies’ novel’. Fru Marianne is, on the surface, a Madame Bovary story with a happy ending. The spoiled middle-class daughter Marianne is purified by her marriage with Börje, the upright son of a farmer; she is put to the test in a “flirtation”, as it is called, with Börje’s best friend, Pål; and she eventually finds her true self in motherhood and marriage.

Marianne’s transformation is illustrated in a dramatic manner: when the novel begins, she lies stretched out on her sofa, indolently reading French novels, “suck[ing] the eroticism of the novels as a child sucks its thumb: if it was not nourishing, at least it offered a kind of consolation”. She is described as a narcissistic sexual being, an object of beauty for men. Three hundred pages later she strides around in rough, striped aprons, energetically occupied in the weaving room and in the vegetable garden. As the mother of a young son, she possesses an insight into herself that is diametrically opposed to the insight she had as a young girl:

“There would be alternating periods of happiness and sorrow, the serenity of happiness, and hard times. She knew that now. Her life would look like other people’s lives: not romantic or like a fairy tale, but prosaic and ordinary.”

Fru Marianne has been read as a conservative contribution to the ‘morality controversy’ of the 1880s – or as a regressive utopia. The same longing gaze back towards a more meaningful and coherent female life in the country household is found in such varied authors as Selma Lagerlöf, Elin Wägner, Agnes von Krusenstjerna, and Moa Martinson, as well as in the, even nowadays, extremely popular novels set in country houses. However, in Victoria Benedictsson’s time, the most closely related author was August Strindberg who, in the preface to Giftas I (Eng. tr. Getting Married), proclaims the peasant marriage to be an ideal. But any reading that stops there is going to ignore the inner resistance of the novel, Fru Marianne, to its own project. Firstly, the comradely marriage between Marianne and Börje is rather an attempt at a more radical version of Ibsen’s modern, idealistic view of marriage – played out on a realistic and historically relevant backdrop: at the end of the nineteenth century, ninety per cent of Sweden’s population still supported themselves as farmers. Secondly, the character of Pål is crucial, and not only to the plot. In the ‘unconscious’ of the text, his refined, ‘female’ eroticism is a disquieting and triggering element, which aestheticises the writing and casts a double gaze upon the plot, the figures, and the motifs. He is an aspect of Börje, of Marianne, and of the yearning that is the driving force of the text. Pål is the erotic and the aesthetic in one figure, who has to be banned at the level of the plot in order for Benedictsson’s realistic project to be carried out. The reader feels the ambivalence, and it is also reflected in the superficial reception of the novel.

A Great Variety of Women

Despite the fact that Victoria Benedictsson regarded Georg Brandes’s rejection of Fru Marianne as a “death sentence” to her writing, she is very productive in the autumn of 1887. She writes stories about the lives of common people, begins writing the novel Modern (The Mother), and finishes the recently discovered comedy Teorier (Theories).

In Teorier we meet a type of woman who, in line with the message of Fru Marianne, represents an alternative to the middle-class ideal of the young girl. In the 1880s, which the Swedish historian of literature Gunnar Ahlström has so aptly called “the gloomy hey-day of the antimacassars”, Benedictsson’s mouthpiece, the young, spirited Hortense, favours occupations completely different from embroidery, piano-playing, and novel reading. She keeps both feet planted firmly on the ground and does not take any interest in the interminable discussions of morality, but rather in cookery and housekeeping.

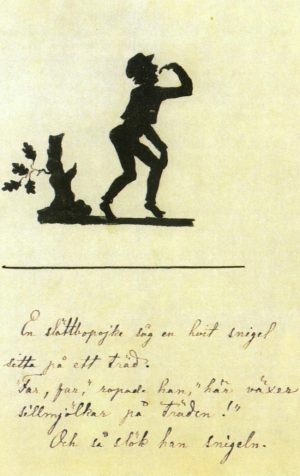

The comedy Teorier (Theories), which was never performed in Victoria Benedictsson’s lifetime, may be her attempt at leaving “Some words to my dear daughter” (“Några ord till min kära dotter”). But unlike in Anna Maria Lenngren’s (1754-1817) famous poem bearing this title and written a hundred years earlier, there is only the slightest bit of irony to be found in Teorier. Here, Benedictsson has her young heroine plainly declare that she prefers Hagdahl’s cookery book to Max Nordau’s social analyses.

Teorier was performed for the first time in 1988 by Stockholms Studentteater (The Stockholm Student Theatre).

Hortense, Marianne, and Selma are figures that go against the stream of female portraits of a determinist stamp, which are characteristic of the 1880s. Their positive air and the happy endings of the works are important parts of Benedictsson’s ‘programme’. Also in the fragmentary manuscript of the novel Modern, which was completed by Axel Lundegård and published in 1888 in both his and Benedictsson’s name, it is a vigorous and self-confident woman, albeit of an intellectual kind, who is described. In the words of her son, she is “a barbarian woman”, who competes with her son’s dollish-pretty and bland fiancée – and loses. For she cannot bring herself to recognise her own identity conflict in that of the other woman: “She was not able to hear that a lack as deep as her own was hiding in that over-excited laugh.”

There is thus an impressive range of female characters in Victoria Benedictsson’s writings. The woman as a sexual object for the man, “the ennobled animal”, is found at the one extreme, and the dream of the woman as a human being rather than a sexual being at the other. However, she never succeeded in portraying a ‘free’ woman who had full access to both intellect and sexuality. Instead, the future image of the woman can be discerned in the tension between the different types of women, representing different life alternatives. As a female author Victoria Benedictsson invests her own divided self and allows her masochistic self-hatred, which is in constant and violent strife with her equally strong, rebellious ambition, to manifest itself in the texts and develop into characters as incompatible as Mrs Victoria and ‘Ernst’. In her repeated attempts to bridge the two antagonistic views of life, Victoria Benedictsson asks: is it possible to survive as a thinking woman, as a female subject with both head and heart intact?

The Bewitched

‘No!’, one is tempted to say upon reading the unfinished prose piece “Den bergtagna” (1888; The Bewitched), written towards the end of Victoria Benedictsson’s life. Concurrently she was working on a play with the same theme, a fragment that was completed by Axel Lundegård and printed in 1890 (Den bergtagna; Eng. tr. The Enchantment). Yet, the manuscript of the play is quite different from the prose version and deals primarily with different ways of handling a love affair and of living with one. In the prose piece, on the other hand, the inherent tragedy of the love affair is described. Step by step, the text records the various stages of the love affair and how the pliant and devoted woman is inevitably entangled in the cunning seducer’s net and driven towards destruction. It is the papers left by a deceased woman that are presented in the frame story, and the note is struck already in the opening words: “I am not defending my life; I am defending my death.”

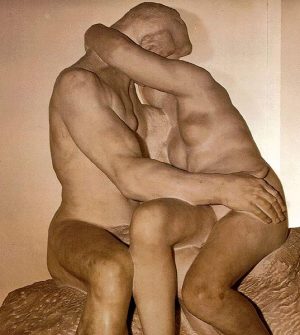

The bewitched woman’s background is that of an ordinary middle-class Swedish woman, but during a sojourn in Paris she comes into contact with a renowned sculptor, who seduces her. The love affair inspires him to make a new group of sculptures, the completion of which means that she has to make room for a new admiring mistress who is to inspire him to make his next masterpiece. These are conditions that the bewitched woman accepts, with open eyes.

But the text contains disruptions and questions that are troubling. At a visit to a museum, the Swedish woman is captured by a challenging self-portrait in which a diametrically opposed type of woman makes her entry: an artist who holds her own! As a contrasting picture to this vigorous woman, the reader is offered a glimpse of the bewitched woman, who in this context – in contrast to the previous first-person narrative – is described in the third person. It is a picture seen from a male perspective, and it shows a content sexual object, a happy woman enjoying the approaching summer – but just like the summer, she is doomed. “What radiated from this face was happiness – a quiet and secret, a deep and mysterious happiness, like the sea in which everything can drown, sink, and disappear, while on the surface the sun is shining and all is calm.” The external, male, gaze can depict her in a bright painting. The inner, female, gaze knows that it is impossible for the bewitched woman to be redeemed once she has stepped into the forbidden, free love, which she knows will end with the man abandoning her: “[…] to me neither happiness nor beauty existed, there was only a desolate emptiness, boundless and deep as the sea I was looking at.”

In “Den bergtagna”, the complex and contradictory aspects of femininity are concisely expressed in the central group of sculptures, “Ödet” (Destiny), in which an “enormous female figure with strong limbs” climbs across the “discarded” body of a drowned young woman, who has the features of the bewitched woman. Apparently totally unaffected by the peacefully resting female corpse, the surreal figure gazes “ahead, strongly and coldly – out into the distance, towards an object that is invisible to others”.

The vigorous ‘over-woman’ can be interpreted as a personification of the masculinity that Brandes applauded, an ideal that possessed the “power to bend others to fit into his plans, and to use them as tools”. But the group of sculptures may just as well be seen as a fixed image of the artistic conflict that Victoria Benedictsson struggled with and never managed to solve.

In “Ur mörkret”, the analysis of the masculine principle was taken to its purest and most deadly logical conclusion. The final image in “Den bergtagna” seems to point to something further still and to suggest that this can go on only as long as the feminine principle allows itself to be trampled down.

“‘Free love’ has poisoned my life – love? – what a name for such a thing! I have to die, for I cannot live. But I shall not be hanged in silence. Shame and ignominy shall cling to my death as they have clung to my life, but that shame shall be lifted up on a scaffold, high above the heads of the crowd; there, a pillory shall stand as a warning, and I shall impudently bite my teeth together during the disgrace, for my destruction shall be a blow to the doctrine that you are preaching, the doctrine that I have always loathed, the doctrine I did not dare to stand up against, because you were stronger than I, because you tied me with the tendons that you had drawn out of my own body, because my thought saw clearly, but my physical nature, like a famished assailant, put its hands in front of its eyes in order to steal a crumb or two in the meantime.

“I hate your doctrine, I hate it – hate it! It has nothing to do with free love. Nothing!

“I have known you for a long time. I have no esteem of you – and yet I love you.

“I have drunk the mountain troll’s potion; I cannot live among my people. But I want to breathe, breathe, breathe before I die – I want to speak my own language and cry out his name, the name that is going to cost me my life!

“The mountain troll – the mountain king. The king of vice – the great, intoxicating, bewitching king of vice.

“But not a human being.”

From Stora boken III (The Big Book), 14 January 1888.

The Diaries

From 1882 until a month before her death in July 1888, Victoria Benedictsson kept a diary, the so-called Stora boken (The Big Book), published in three volumes in 1978-84. Supplemented with calendar notes and correspondence with her closest friends, Axel Lundegård, Ellen Key, Gustaf af Geijerstam, her stepdaughter Matti, and others, it provides an exceptionally rich source of biographical material. The diary can be read as a moral chronicle of the 1880s in the Nordic countries. Benedictsson is adamant that nothing human should be alien to her. Everything that has to do with love or sexuality, with the relationship between the sexes, interests her and is noted down in Stora boken. Often she uses a code in order to be able to inform her “Ernst” or “Old book” about her secret thoughts on abstinence, birth control, syphilis, and prostitution, all the things that women were not supposed to know anything about.

“Good night, old Ernst! I am glad that you are not abandoning me. Sleep well, you sceptical old fogey. You and I, we are some couple! Ernst and Victoria.”

From Stora boken (The Big Book).

In Stora boken the parties, the gossip, and the scandals of family life in the small town of Hörby are described as well as her encounter with the big city:

“Stockholm, 5 November 1885. I still feel so terribly lost and a stranger. And then my foot really hurts. But there is something else. My whole being is tormented by a suppressed, brewing hatred. All these people are the enemies of my innermost aspiration. They think of life as a game, and to me it is serious. Everywhere I am met by a haze of lies and falseness; it is as if it is going to choke me, and at the same time my muscles tighten in powerless fury. What are these people rambling on about! Women’s rights, the workers’ cause. Idle talk. Oh, it is all idle talk! […]

“I wish I were in a big city where nobody knew me, where I were thrown out like a small stone and able to hide on the bottom, able to feel life rubbing against me on all sides but not being upset by it, only being shaped, slowly being shaped into something perfect […].”

A telling example of the difficulty involved in portraying a complex woman is the novel about Lady Macbeth and the artist’s calling that Ellen Key, in her book about her friend, says that Victoria Benedictsson dreamed of writing. Already in 1880, Victoria Benedictsson writes in Stora boken (The Big Book) about her fascination with this female figure, and in 1885 she tells Axel Lundegård that “[e]verything will come to life in my long novel Lady Macbeth, unless I lose my touch or die before then. What a childhood! A goldmine. And what a phenomenal memory I have for facts!”

The strength of her identification with the figure emerges from these lines written a couple of months before her suicide: “I understand Lady Macbeth, for my hand also seems to me to have got a stain that cannot be washed away; it is the feeling that someone else is looking down upon me. I am so proud that I cannot bear that.”

In Victoria Benedictsson’s imagination, Lady Macbeth is the active and proud woman who accepts the consequences of her ambition – a woman whom it is nearly impossible to describe in sympathetic terms, especially if she is also to personify the artist’s calling.

Here are offered keen-eyed psychological portraits of many of the period’s young authors, such as Ola Hansson, Oscar Levertin, Stella Kleve, Anne Charlotte Edgren Leffler, Alfhild Agrell, and Ellen Key. And above all Georg Brandes, who turns her into the bewitched woman. Before Victoria Benedictsson is dragged into the magic circle of the Mountain King, she sees herself more as an author than as a human being. This is also how she wants to present herself at encounters with her colleagues in Stockholm or Copenhagen. The big question is how a simple, ascetic attire can be combined with supreme elegance. “A shadow of Catherine of Medici, and there you have the style […]. An ‘intellectual aristocrat’, an old, tyrannical, hard, cunning woman: there you see what I can signal with my dress and what I should signal. Above all: old. Otherwise all the other things will lack effect. Black plush in the light, black satin during the day; jets in daylight and black pearls in lamplight; on my head black velvet or black spangle. Heavy, expensive, indifferent. Voilà.”

Victoria Benedictsson’s conscious staging of herself as an older, sexually neutral artist is an important part of her identity as an author. It is against this background that it becomes clear why her relationship to Brandes was so disastrous. When he looks down upon her both as an author and as a woman, the studied attire falls off, and she stands completely naked, bereft of her armour and thus, in her own eyes, bereft of the possibilities of life.

The diary begins in a harmless way as an author’s ‘storehouse’ with anecdotes, folktales, copies of letters, fragments of conversations, and observations, but before long it changes character and becomes an instrument of self-analysis. At an early stage, Victoria Benedictsson realised that her diary might be published, and, starting in 1885, her editing efforts become obvious. Her demand for truth involved her having to appear in all her complexity and also exposing her less appealing sides. Gossip, indiscreet speculations, and above all a drawn-out analysis of her own feelings slowly gain prominence in the pages. She sees herself most clearly in her relationship with men, above all with her ‘comrade’ Axel Lundegård – their emotionally loaded intellectual relationship dominates Part Two – and with Georg Brandes – who dominates Part Three.

In her diaries Victoria Benedictsson takes the step into modern times. It is a contemporary of ours who is speaking here and who, thanks to her unswerving loyalty to her own experiences, makes a Virginia Woolf or an Anaïs Nin seem tame. After Victoria Benedictsson nobody else has, in an equally ruthless way, tested introspection as a method to uncover the contradictions of the female sexual being. Read closely, the diary, with its increasingly detailed analysis of a woman’s state of mind, leaves the impression of a stubborn refusal to play the men’s game. It also conveys a persistent striving for truth in the erotic as well as in the intellectual power struggle between the sexes. Victoria Benedictsson fearlessly treats her own experiences as raw material for literature. Thus, for example, her relationship to Brandes is gradually given the character of a self-fulfilling prophecy. For Victoria Benedictsson had at a much earlier stage noted down the outline of the dramatised rendering of the tragic love story, which took place in 1886-88. Scenes from other close relationships to men, such as her love interest in the Swedish-American Charles Quillfeldt at the end of the 1870s, or her friendship with the young Axel Lundegård in the middle of the 1880s, are written into the Copenhagen tale about Georg Brandes, with some lines rendered verbatim.

The diaries follow very closely the divergent curves described by Victoria Benedictsson’s writing career and life experiences up to her final suicide. “My diaries are not to be destroyed […]”, she wrote, well aware that it is with her diaries that she takes the step into modern times.

Many female authors used the Modern Breakthrough to discuss the question of how the woman was to develop a certain independence in the context of marriage, often through paid or creative work. Others, as for example Agrell and Edgren Leffler, took a step further in their criticism of the patriarchal institution of marriage. But only few, apart from Stella Kleve and Victoria Benedictsson, ventured to address the burning question as to how the power structure leaves its traces on female sexuality; or the question as to how female desire could be realised in a society with an institutionalised double standard of morality. It was considered inappropriate for women to openly express their opinion on the issue of sexuality. It was bad enough, the establishment thought, when the male authors did so.

Translated by Pernille Harsting