The last year of World War II was a memorable time in Swedish literature. While attracting just as much international acclaim as Selma Lagerlöf’s Nils Holgerssons underbara resa genom Sverige (1906-1907; Nils Holgersson’s Wonderful Trip through Sweden, Eng. tr. The Wonderful Adventures of Nils and the Further Adventures of Nils Holgersson), Pippi Långstrump (1945, Eng. tr. Pippi Longstocking) marked the beginning of a whole new way of looking at children and the literature written for them. While affecting to be a humorous story and nothing more, it harboured the same ambitious educational pretensions as Lagerlöf’s schoolbook, and had the same profound impact. Aside from Lagerlöf, Astrid Lindgren (1907-2002) is now the most well-known and widely read Swedish author; her books have been translated into some sixty languages.

Her first book, Britt-Mari lättar sitt hjärta (1944; Britt-Mari Opens her Heart, Eng. tr. Confidences of Britt-Mari Hagström), was the runner-up in a competition for fiction aimed at teenage girls. She sent her new manuscript to Albert Bonnier’s Publishers the same year. They turned it down. Rabén & Sjögren, a brand new children’s publisher, brought out Pippi Långstrump, which won first place in their competition. The book attracted immediate attention and provoked a public debate about how children’s literature should be written and what values it should convey.

On 18 April 1946, the well-known literary critic John Landquist launched an all-out attack on Pippi Långstrump. That set off the “Pippi Feud,” just as he had been responsible for the “von Pahlen Feud” in 1934. As had been the case with Agnes von Krusenstjerna, he questioned Lindgren’s morality and sanity. “The unnatural girl” left him with the “sensation of something disagreeable that claws at the soul”, and the whole book reminded him of “a madman’s fantasy”. Uneasy parents and offended guardians of public morality quickly joined him. The Elementary School Teachers’ Association of Sweden took the side of the accusers, while the newspaper of female teachers pleaded for the defence.

Pippi is fundamentally a defenceless and solitary child. Her mother died when she was a baby. She sailed “the seven seas” with her father, a seafaring captain – and a pirate captain in her fantasies. He “blew into the sea during a storm” and disappeared.

One of Lindgren’s most effective techniques is to let imagination engulf reality. The interpretation of the world by a ‘lying’ child triumphs over adult rationality. Pippi refuses to believe that her father has drowned. She is sure that he drifted ashore on a south sea island and has become king of the cannibals. And Pippi Långstrump går ombord (Pippi Longstocking Goes On Board, Eng. tr. Pippi Goes On Board), the sequel, reveals that she knew exactly what she was talking about.

The most extravagant childish dream of omnipotence comes true in the story of Pippi. With irrefutable logic, Lindgren demonstrates what a solitary child needs to avoid being crushed in a world of hard-headed pragmatism that despises weakness. Pippi is the “strongest girl in the world” – and the richest to boot. She owns a suitcase of her father’s gold coins, as well as Villa Villekulla, his dilapidated old house, and can take care of herself. When two policemen come to bring her to an orphanage, she mercilessly pokes fun at them before picking them up and carrying them away.

Pippi also has certain spiritual qualities that enable her to survive. In her way, she is the prototype of ‘a whole person’. She does whatever she wants to do, which is the secret of her unsurpassed attraction for young readers of both sexes. Uncontaminated by cultural inhibitions, she embraces every possible human quality and does not repress any of her potential.

Pippi’s declaraction of independence from her father is not without its pathos. The farewell scene is a classic tear-jerker:

“‘No, Papa Efraim,’ cried Pippi. ‘I can’t do it. I just can’t bear to do it!’

‘What is it you can’t bear to do?’ asked Captain Longstocking.

‘I can’t bear seeing anyone on God’s green earth crying and being sad on account of me. Least of all Tommy and Annika. Put out the gangplank again. I’m staying in Villa Villekulla.’

Captain Longstocking stood silent for a minute.

‘Do as you like,’ he said at last. ‘You always have done that.’

Pippi nodded.

‘Yes, I’ve always done that,’ she said quietly.

They hugged each other again, Pippi and her father, so hard that their ribs cracked.”

(Pippi Goes On Board, p. 136).

Children of Reality

Lindgren’s sensitivity to children’s feelings and perspectives, along with her uncompromising willingness to take their side, is a modernist trait that links her work to the radical psychology of permissive child rearing that made inroads in Sweden between the wars. Just like in Pippi Långstrump, rote learning, strict discipline, and corporal punishment were called into question. The war years were a setback in that respect. Order and discipline were back in fashion. Not coincidentally, the book about a nine-year-old girl who is adamant in her demand that children have the right to protest, revolt, and think new thoughts was written during the darkest years of the war. Her magical powers enable her to survive at a time when vulnerability, sensitivity, growth, and development are imperilled as never before. As the strongest girl in the world, Pippi is a child in every sense of the word; she speaks for all children and fights for their rights in a benighted and uncharitable age.

The new, genre-defying feature of Pippi Långstrump is its peculiar blend of reality and fantasy. Most of Lindgren’s writing inhabits that borderland. While some of her works are demonstrably realistic, they are nevertheless about the ability of fanciful children to live in a world of play and imagination.

Certain similarities have been noted between Pippi Longstocking and the red-haired heroine of the Canadian children’s classic Anne of Green Gables (1908) by Lucy Maud Montgomery (1874-1942). But there is certainly a Swedish antecedent as well: Ester Blenda Nordström’s trilogy about Annmari, a rambunctious orphan. The first volume was En rackarunge (1919; A Young Rascal), and the last one was Patron förlovar sig (1933; The Squire Gets Engaged).

Emil i Lönneberga (1963; Emil in Lönneberga), Nya hyss av Emil i Lönneberga (1966; New Mischief by Emil in Lönneberga, Eng. tr. Emil’s Pranks), and Än lever Emil i Lönneberga (1970; Emil in Lönneberga Still Lives, Eng. tr. Emil and His Clever Pig) reinvigorate and add depth to the durable ‘little rascal’ genre. Emil is a Pippi of everyday life, an instigator whose mischief undermines the patriarchal order in his rural household. He is portrayed as an essentially kind-hearted child of nature, and his name links him immediately to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Émile, the classical treatise on enlightened education. Emil inevitably draws the longest straw in his showdowns with the adult world. Lindgren claimed that she most cherished her Emil books. The trilogy, buoyed by its consummate narrative style, is among the most vibrant and descriptive portrayals ever written of rural Sweden in the early twentieth century. Emil lives on as one of Lindgren’s good and strong children who position themselves outside the adult world and its values while intervening and changing its way of doing things by virtue of their spontaneous, naive perspective.

The Story of a Faraway Land

The most lonesome and abandoned child in Lindgren’s world is Karl Anders Nilsson, who becomes the prince of an imaginary kingdom in Mio, min Mio (1954; Mio, My Mio, Eng. tr. Mio, My Son). His foster-parents are strict and devoid of feeling. Sitting on a bench in Stockholm’s Tegnérlunden Park on a dark autumn afternoon, he experiences a miracle. A genie, shut up in an ordinary beer bottle – Lindgren always provides every last detail – takes him on a dizzying voyage beyond the stars, reminiscent of One Thousand and One Nights. He is transported to a faraway land, “where all our wishes are wondrously fulfilled” in the words of Edith Södergran’s “The Land That Is Not”, a poem that echoes through Lindgren’s bittersweet tale of longing. In the romantic wonderland, Karl Anders Nilsson meets a king who tells him that he is really Prince Mio, and who loves him just as unconditionally as he had always yearned for his earthly father to do.

Mio, min Mio is a cruel and beautiful tale about the difficult but inevitable battle between good and evil, the evolution of a human being from a state of fear and oppression to one of courage and integrity. Lindgren uses the stylistic devices of folk-tales and myths: the epic triad, formulaic refrains, and the hero’s journey. Mio embarks on an agonising odyssey through the barren land of evil and the dark, ominous castle to slay the wicked Sir Kato. Not until he carries out his mission and pierces Sir Kato’s stone heart with his magic sword does the land begin to bloom again, and all the living creatures Kato had imprisoned and enchanted re-assume their proper form. The father-son reunion is depicted as a rebirth.

The unique feature of Lindgren’s heroic tale is that a child narrates it. It is told not by an omniscient narrator, but through the consciousness of the experiencing subject. An atmosphere of here and now – an immediate presence – prevails, like a game that absorbs children so completely that their fantasy world takes on the contours of truth. Nevertheless, reality makes its appearance over and over again. The characters in the story of Mio are clearly based on the people who surround Karl in his everyday life.

“Never Violence!” was the title of a speech that Lindgren gave upon receiving the German Booksellers’ Peace Prize in 1978. “So is there any possibility at all of our changing fundamentally, before it’s too late?” she asks rhetorically, and answers, “I believe that we should start from the bottom, with the children.” If they were raised in an atmosphere of love, security, and respect, they would not perpetrate violence. Violence is not a basic human instinct. Most people dream of a life in peace, close to nature, and secure among their loved ones.

Fantasy and reality are one, Lindgren seems to be saying. What we create and dream about is just as true and important to us as the external world, maybe more important.

The War Novel

Bröderna Lejonhjärta (1973; Eng. tr. The Brothers Lionheart),Lindgren’s second mythical masterpiece, returns to the hero’s journey, but in another way. All the ingredients of Mio, min Mio are still there: the quest, the mythical kingdom, the difficult mission, and the battle against evil. Not only must a tyrant be neutralised this time, but a dragon has to be slain, a knight’s ultimate good deed. Nor does the hero narrate the story; the honour falls on his squire and younger brother, nine-year-old Karl Lion.

The book is a suggestive and suspenseful coming-of-age story that traces a young and frightened boy’s path to self-confidence and emotional maturity. His idol and guiding star is his brother Jonathan, the true Lion Heart; the theme of the tale is his capacity to overcome his anxiety in order to stand loyally by Jonathan’s side through thick and thin, even in the “final darkness” – symbolised by the dragon’s cave – and the instant of death. Jonathan Lionheart is not only a triumphant hero who courageously and energetically leads a struggle of liberation for an oppressed people, but a martyr who gives his life in the battle for right and justice.

Bröderna Lejonhjärta is Lindgren’s great war – or perhaps antiwar – novel. For a ‘children’s book’, it contains unusually compelling and shocking descriptions of violence and oppression. Jonathan, who refuses to bear arms or kill, is a symbol of pacifism as a necessary dream and dearly-bought possibility. The hardest question Lindgren asks is both timely and universal: Can violence and oppression be defeated by peaceful means? “There are adventures that should not happen”, he says to Karl.

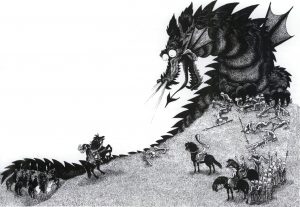

Bröderna Lejonhjärta confronts the greatest source of human anguish, the fear of suffering and death. Katla, the dragon, is the symbol and focal point of that horror. As the tyrant’s most secret weapon, she lurks for a long time as a nameless threat, a hint of unmentionable terrors. She devours all living creatures that come her way. Not only that, but she belches out poison and flames that paralyse and kill at a distance.

The travails of the Brothers Lionheart in the dragon’s cave constitute an inner journey through darkness, trepidation, and chaos in which the fragile ego is threatened by inundation and annihilation. But the death-dealing monster can also be interpreted as a metaphor for the nuclear peril, a force so destructive and indestructible that the only way to neutralise it is to bury it in an underground cave for thousands of years. Even the Brothers Lionheart succumb to Katla’s lethal radiation.

Lindgren’s sombre tale confronts the fear and awe that death evokes. She lays bare a subject that our civilisation painstakingly represses, particularly when it comes to children. Bröderna Lejonhjärta has made it easier to talk with children about war, violence, suffering, and mortality. Resistance, courage, and the hope of a better life – both for humanity as a whole and for the individual soul – are also more respectable topics thanks to Lindgren’s book.

By taking children seriously, Lindgren signalled a new epoch in juvenile literature. She showed that no question is too profound, too difficult, or too controversial for readers of any age. Children experience anxiety, passion, rage, hatred, compassion, and the need to search for life’s meaning the same way as adults do. A number of Nordic female authors, whether they followed in Lindgren’s footsteps or not, have written good children’s literature that explore profound existential and psychological themes. Among them are Tove Jansson and Irmelin Sandman-Lilius in Finland; Maria Gripe, Gunnel Linde, and Barbro Lindgren in Sweden; Anne-Cath Vestly and Karin Bøge in Norway; and Cecil Bødker in Denmark.

Bröderna Lejonhjärta alludes to Hagar Olsson in a fascinating way. “It is still the campfires and storytelling times” in the magical land of Nangijala, Jonatan says. Jag lever! (1948; I’m Alive!), Olsson’s sweeping critique of modern civilisation, puts it this way:

“People of today are frightened and alienated from their own civilisation, because something within them bears the memory of an ancient era, the days of storytelling and campfires […]. The atom bomb hovers over their heads like a preternatural monster that they themselves have conjured up without knowing whether they can tame the force that they have released.”

Lindgren is Lagerlöf’s heir from many points of view. In the guise of myth and fairy-tale, she sounds the depths of the eternal questions: the meaning of life and death, joy and fear, love and hate, good and evil. The difference is that she was never a Nobel Laureate or even a member of the Swedish Academy. Is that because she ‘wrote only for children’? The guides to fiction inevitably classify her works under Juvenile Literature, a convenient way to exclude them from the universal tradition.

A Novel for the Whole Family

While Bröderna Lejonhjärta is Lindgren’s great war novel for children, Ronja Rövardotter (Eng. tr. Ronia, the Robber’s Daughter) her last work, is for the whole family.

Ronia grows up in the castle of the father, Matt the robber chief. Her strongest impressions, however, are of the surrounding wilderness. Lindgren masterfully describes the great Swedish forests with their mosses, spruces, marshes, and rapids, their wood-anemones in the spring and lingonberries in the autumn. But she also fills them with mystical beings: grey dwarfs, rumphobs, and wild harpies – various projections of Ronia’s fear of being devoured by the blind forces of nature.

But the real dangers in her life are not the elements, but inside her father’s castle, the abysses that a growing girl can fall into at any minute. Erratic and autocratic, Matt goes from fits of rage to outbursts of laughter as he tyrannises his twelve robbers, wife, and daughter. Nevertheless he worships Ronia, and she has ambivalent feelings about him: loving but anguished, intimate but beset by harrowing tensions. The father-daughter conflict draws from Greek tragedy, but perhaps most of all from Selma Lagerlöf’s Kejsarn av Portugallien (1914; Eng. tr. The Emperor of Portugallia). Like Jan of Ruffluck Croft, Matt experiences a stab of boundless, ill-fated love when his newborn daughter is placed in his arms.

Ronia’s mother Lovis is strong and secure, keeping her volatile husband and his twelve cronies under control with a firm hand. She supports and encourages Ronia’s emancipation. Ronia’s emotional conflicts have to do with her father and their relationship. When she violates the Law of the Father with her symbolic leap over the Hell’s Gap to join the son of Borka, Matt’s arch-enemy, he breaks down and howls: “I have no child!”

Ronia takes off and settles down in a cave in the woods with Birk, the son of a robber. A classic triangle drama emerges between a growing daughter, her father, and his rival. Matt stomps and screams with jealousy and injured pride. He and Ronia are not reconciled until he comes to realise that she has the right to leave home, live her own life, and be with the person she loves.

She revolts against everything he stands for, his values and way of life. Matt wants Ronia to succeed him as robber chief when she grows up. Her first rejection of him comes when she realises what his ‘work’ involves. At the end of the book, she and Birk – the people of the future – resolve to live differently than their fathers, renouncing the ideology of violence and power that seeks to exploit and oppress others.

Ronia may be the most vivid of Lindgren’s various combative and rebellious young characters. The book concludes with her shout of joy that spring has come, her exaltation at being alive.

Translated by Ken Schubert