Ruumiin ikävä (1930; The Body’s Yearnings) by Iris Uurto (1905-1994) is about a woman named Paula Lassila who leaves her husband. Like Lilith, who according to Midrashic literature fled from the Garden of Eden to satisfy her sexual needs among the daemons, Paula is driven by erotic passion.

Such a bold depiction of sexuality by a young female author scandalised conservative cultural circles. But Tulta ja tuskaa (1930; Fire and Pain), Uurto’s first book of poetry, had left no doubt about her values: “I shun not sin, / but indifference, cupidity, vulgarity.” Her description of instinct and the libido were inspired by the new psychology of the age. Inevitably, her books were fodder for 1930s controversies about morals in literature.

The Finnish debate came to a head in 1936. Among the books in the line of fire were Uurto’s Kypsyminen (1935; Maturation) and Katuojan vettä (1935; Gutter Water), a novel by Helvi Hämäläinen (1907-1998). Uurto achieved recognition among leftwing intellectuals and cultural liberals, who accepted the direction psychology was taking. They also shared a positive view of sexuality, although the leftwingers spoke of socialist vitality and the liberals of vitalism. The third front line consisted of conservative aestheticians. They were critical of the new literature’s materialistic and scientific orientation, which they associated with leftist viewpoints. In their eyes, Uurto’s books encouraged immorality and subversive tendencies.

Revolt against Middle-Class Morals

The revolt in Kypsyminen is relatively innocuous. The portrait of Mrs Pallas, who regards marriage as a matter of ownership, is an ironic commentary on middle-class morals. She does not even have a name of her own apart from the one her husband has bestowed upon her. She has devoted twenty years to her family’s welfare and polished her martyr’s halo. Meanwhile, her sacrifice has turned her into a monster whose love binds but elicits guilt feelings rather than reciprocity. Her marriage ends in divorce and the household breaks up. Uurto also offers another option. At the end of the book, Mrs Pallas’s stepson Lauri reaches out to “comrades, brothers” and adopts a collectivist worldview, making his abode among all of humanity.

Rakkaus ja pelko (1936; Love and Fear), Uurto’s next novel, takes place during the Depression and offers more social criticism. Unemployment and financial ruin led to many tragedies during that period. The protagonist is Kaarina, Mrs Pallas’s stepdaughter. The man she loves will not accept the responsibilities that come with a family, and she gets an abortion so that he will not have to make a commitment.

Uurto’s novels and Hämäläinen’s Katuojan vettä take place in Helsinki’s working-class district, where they lived in the 1930s. One of their friends was Katri Vala, whose poetry collection Paluu (1934; Return) evokes the same milieu. Both authors were advocates of social justice and children’s rights.

Timanttilakien alla (1938; During the Diamond Laws) reveals Uurto’s disillusionment with leftwing idealism. Pietari Nord, the protagonist of the novel, feels alienated from other artists as well as from the political activists he knows. He has been so hurt and rejected as an artist that his humanity seems to have been stripped away, and with it his ability to create. Faced with such a hopeless situation, he sees suicide as the noblest way out.

The theme of the creative individual’s homelessness re-emerges in Uurto’s greatest accomplishment, Ruumiin viisaus (1942; The Wisdom of the Body). Among the characters is Siiri Halava, a mathematical genius who leads a tragic existence, even when it comes to sex. An intelligent woman, she sets out to use her intellect and money to control her lover rather than play the subordinate role herself. Her project ends in failure, and she ultimately kills herself. The resolution of her dilemma is fairly typical of books by women who have chronicled the revolt against conventional feminine roles.

Women’s Freedom

Finnish female authors were active participants in the 1930s discussion of birth control and abortion that gathered momentum during the early years of the Depression. Katuojan vettä, the first popular success by novelist Helvi Hämäläinen (1907-1998), was a plea for motherhood as a natural event in the course of a woman’s life. Her creative powers put her on a par with Mother Earth, just as she merges with the fertile soil during the act of love. Both men and women are children of nature. Elsa, the protagonist of Hämäläinen’s Tyhjä syli (1937; The Empty Lap), furiously demands her right to be a mother. Her breasts quivering and her feet stamping, she seduces a stranger so that she can have the child her husband is incapable of giving her. Such an embodiment of femininity is difficult to reconcile with the myth of the Immaculate Conception or the cult of the Virgin Mary. Hämäläinen’s demands on behalf of motherhood combined with a satisfying sex life approach Ellen Key’s ideal.

Reviewers associated Lumous (1934; Enchantment) and Tyhjä syli with D. H. Lawrence’s sexual mystique. Whereas Hämäläinen portrays women as the active party, however, Lawrence uses them to confirm male virility. Both authors extol healthy instincts, but the roles they assign to women and men are the mirror images of each other. Lumous can more usefully be compared with Uurto’s Ruumiin ikävä. The heroines of the two novels leave their husbands for the sake of sexual passion.

Their rebellion gradually spreads from the physical to the spiritual plane.

Physical and Spiritual Love

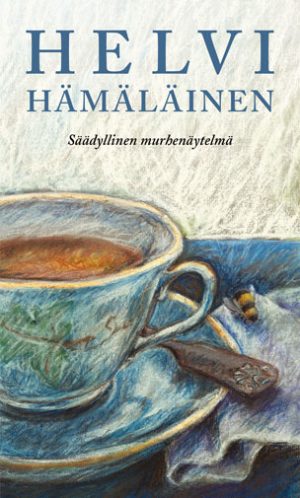

The bold anti-Nazism of Säädyllinen murhenäytelmä (1941; A Modest Tragedy) reated problems for Hämäläinen. The original 1939 edition was cancelled. The novel features two main plots, the first of which involves the adulterous relationship of an archaeologist and his maidservant. His wife Elisabeth closes her eyes to his escapades just as Europe closed its eyes while Hitler was forging his plans of conquest. Elisabeth’s husband excuses his behaviour as an expression of beauty and joy that should bring her the same aesthetic satisfaction. The young woman exemplifies a fresh brand of sexuality. The “erotic maelstrom” of the new age deprives men of their sense of direction. But the fundamental problem is that the “spirituality” represented by the archaeologist and his wife is spurious; skilfully and ironically, Hämäläinen describes the ground rules of this “tragedy of the educated.”

The true tragedy, however, is played out somewhere else. Naimi, another main character, takes her ex-husband back after twenty years of divorce. Even though his infidelity had destroyed their marriage, he remains the love of her life. She has a vivid recollection of the purple bedroom of their youth:

“The weariness that followed passionate lovemaking had always been accompanied by images that shimmered like nebulae in her brain. She held the head of her beloved between her hands, as her inner eye watched a bee with golden wings and a rose in its mouth ricochet off the ceiling. She laughed with joy; her teeth were sharp and lustrous, with just the slightest tinge of blue.”

Translated by Ken Schubert